Success or struggle: ROA as a true measure of business performance has been saved

Success or struggle: ROA as a true measure of business performance Report 3 of the 2013 Shift Index series

31 October 2013

Declining return on assets (ROA) doesn’t fit with the stories commonly reported about firm performance and the business environment.

Companies are broken, and many don't know

The news today paints an upbeat picture on many fronts. Corporations report record profit levels.1 The economy has recovered at a steady pace of 1.8–2.4 percent over the last three years.2 Stock market rallies restored major indices to prior levels and beyond. Housing prices have stabilized and have begun to increase nationally.3 Manufacturing activity is showing signs of expansion.4 All aggregate signs point to positive outcomes for the time being.

Learn More

What we think now: Read an update from John Hagel as featured in Deloitte Review, issue 22

Subscribe to receive insights from the Center for the Edge

Read Deloitte Review, issue 22

Create a custom PDF or download Deloitte Review, issue 22

Yet, other metrics tell a different story, one of increasing pressures and stress for companies, executives, and employees. An increasing topple rate indicates that US companies are struggling to maintain their leadership positions as revenues and market share prove vulnerable.5 Over the past four years, Chapter 11 business bankruptcies have been at a level not seen since the mid-1990s.6 High-profile bankruptcies, such as Linen n’ Things and Blockbuster, and the automobile industry crisis in 2008 highlight the potential for seemingly successful companies to suffer rapid, irrecoverable downturns. Even without the financial meltdown of 2008, the last several decades of rapid technological change and increasing global economic liberalization have put increasing pressure on traditional business models. These pressures are felt by executives charged with pursuing profitable growth and workers who must stay relevant as technology and business models change. The cumulative effects of long-term changes, driven by digital technology and public policy shifts, which are transforming the global business economy comprise an era we call the Big Shift.

About the Shift Index

We developed the Shift Index to help executives understand and take advantage of the long-term forces of change shaping the US economy. The Shift Index tracks 25 metrics across more than 40 years. These metrics fall into three areas: 1) the developments in the technological and political foundations underlying market changes, 2) the flows of capital, information, and talent changing the business landscape, and 3) the impacts of these changes on competition, volatility, and performance across industries. Combined, these factors reflect what we call the Big Shift in the global business environment.

For more information, please go to www.deloitte.com/us/shiftindex

This story is embodied in the economy-wide, secular decline in return on assets (ROA) over the last 47 years. The decline signals companies’ decreasing ability to find and capture attractive opportunities relative to the assets they have. Companies lack a clear vision or the ability and commitment to execute a long-term strategy. The long-term trajectory of ROA, rather than a snapshot in any given quarter or year, reveals how effective a company is, over time, at harnessing business opportunities in a highly uncertain environment.

ROA is not a perfect measure, but it is the most effective, broadly available financial measure to assess company performance. It captures the fundamentals of business performance in a holistic way, looking at both income statement performance and the assets required to run a business. Commonly used metrics such as return on equity or returns to shareholders are vulnerable to financial engineering, especially through debt leverage, which can obscure the fundamentals of a business. ROA also is less vulnerable to the kind of short-term gaming that can occur on income statements since many assets, such as property, plant, and equipment, and intangibles, involve long-term asset decisions that are more difficult to tamper with in the short term.

This period of technological change began in 1965—a few years before the invention of the microprocessor. Shortly thereafter, the oil shocks of the early 1970s created another massive disruption. Throughout this time, changing public policies fueled increasing global competition. The result: a decade of negative returns for shareholders and a permanently changed landscape for executive decision making. A school of thought emerged that the main goal of a company was to maximize returns for shareholders; if companies focused on shareholder returns, everything else would fall into place. The side effect of this thinking was to establish a culture of short-term decision making in the highest echelons of business.7

To be fair, operational execution will always be fundamental to the health of a business. A company’s ability to execute on established commitments bolsters its credibility to customers, suppliers, and creditors alike. The danger comes when assessments of the environment, and thus, the strategic direction, are too heavily dependent on the short term. One way to shift to a longer perspective is by considering the effects on supply and demand from fundamental shifts such as globalization, greater consumer choice, and disruptive business models. Both established competitors and new players may be eroding the customer base. The fundamental question for companies pertains to how their products and services provide greater value for their customers. Within this context, companies must question whether they are making the investments needed to prepare for the long term.

The lasting legacy of this short-term focus is not increased certainty, but rather, greater uncertainty and risk, which can lead to value destruction. Today’s technology allows information to travel more seamlessly within and across organizations. This amplifies the effects and risks of each decision. Decisions that disproportionately focus on short-term shareholder returns may detract or even prevent a company from creating long-term value. The recession that began in 2008 provides an example from an industry thought to be adept at managing risk, the financial services industry. The risk models designed to weigh the downsides of the hottest new financial product—mortgage-backed securities that formed collateralized debt obligations (CDOs)—only accounted for the most recent, short-term performance to assess the sensitivity of future performance. Rather than challenge the fundamental assumptions of this practice, most financial institutions adopted these methods, realizing quick gains without concern for systemic market implications.8

An example of a company that is focused on a long-term strategy is Starbucks. The company has sustained several downturns and continues to grow. Despite the temptation to maximize short-term returns to a single group of constituents, Starbucks continued to uphold policies geared toward workers’ satisfaction, such as making health care available for all employees, regardless of weekly hours. During the most recent downturn when it would have been understandable to adapt to economic conditions and reduce investment, Starbucks considered a longer-term view and upgraded its expensive espresso machines to enhance the consumer experience.9

The turmoil and uncertainty brought about by the current period of exponentially improving technological performance shows no signs of subsiding.10 In this environment, the long-term trajectory of ROA is the best financial scorecard of a company’s health and an indicator of how its decisions play out. Understanding the trajectory provides a foundation for taking a longer-term perspective that can help companies shape winning strategies.

The decline in ROA doesn’t fit with the stories commonly reported about firm performance and the business environment. This paper will first address four of these seeming paradoxes: rising corporate profits, long-term economic growth, increasing labor productivity, and more consumer choice. Then it will delve into the effects of the Big Shift on major components of ROA. Finally, it will explore the perils of short-term thinking and chart a course back to long-term thinking.

2013 Shift Index

To better understand this year’s Shift Index, as well as to learn about ways to begin to create and capture value in this environment, we invite you to take a deeper look at our 2013 Shift Index research reports:

Unlocking the passion of the explorer

From exponential technologies to exponential innovation

2013 Shift Index metrics: The burdens of the past

Lessons from the edge: What companies can learn from a tribe in the Amazon

Many economic and market indicators suggest everything is fine; it is tempting to believe that as the economy continues to recover, companies will find ways to thrive. However, beneath the surface, consumer needs, worker capabilities and expectations, and the very nature of work is changing. Companies, particularly large ones, have not yet addressed the impacts of these fundamental shifts. As institutions’ strategies, structures, and practices become increasingly ill-suited for the world of technology-enabled flows, they are confronted by contradictory evidence and short-term performance that makes it easy for leaders and investors alike to dismiss the indications of long-term performance deterioration. We’ll begin by exploring four of the most compelling paradoxes and why good numbers aren’t always good news.

Paradox 1: Many companies are reporting record profits, but longer-term trends suggest they are struggling.

Part of the answer lies in a company’s ability to generate returns and turn a profit. The mass media tends to focus on income statement profits as the one true measure—after all, isn’t it the bottom line that matters? Absolute profits, however, matter little—at a minimum, profits should be considered relative to total revenue to get a sense of whether profits are rising faster or slower than revenue. But even that analysis overlooks a critical component of business activity: the assets required to run a business. Ultimately, companies need to earn a healthy return on those assets in order to stay in business. ROA captures how well a company used its assets to create value. Thus, ROA is a more effective measure of fundamental business performance. The long-term trend for ROA has been decreasing for decades across the economy and across industries (see figure 1).11

Another part of the answer lies in how long companies can maintain leadership within a sector. If the long-term trend in changes in market leadership were relatively flat, the recent turmoil among sector leaders might be explained away as a cyclical effect. However, the topple rate, a measure of how rapidly companies lose their leadership positions, has increased by 39 percent since 1965.12 This suggests something is awry. Even very successful companies appear unable to maintain leadership positions as long as they used to.

Richard Foster described the phenomenon of companies generating lower returns from assets and failing to hold onto market leadership. He found that the tenure of companies on the Standard & Poor’s 500 (S&P 500) has declined from 61 years in 1958 to 18 years in 2012. This suggests that, 15 years from now, 75 percent of the S&P 500 will have turned over. Whether the result of acquisition, bankruptcy, or dramatic deterioration in performance, the imperative remains: Companies need to rapidly develop and scale new businesses, and they need to shed legacy operations that no longer meet the needs of the marketplace.13

In retailing, a sector directly impacted by the changing consumer behavior, a number of bankruptcies illustrate the incomplete story told by short-term performance metrics. Borders, Circuit City, and Linens ’n Things each reported consistent profits right up until beginning a rapid decline that eventually led to a liquidation of their assets.

Other sectors, such as technology, telecommunications, and media, are also experiencing effects of the Big Shift—including digitization and the free flow of information—and a number of former industry leaders have been the target of high-profile acquisitions and restructuring events. A widespread decline in ROA and an economy-wide increase in topple rates suggest it may be just a matter of time before similar events expand to other industries.

Paradox 2: Labor productivity is rising, but companies are still in trouble.

It’s true that in aggregate, workers are becoming more productive. The output per worker is higher than at any time in history. As a whole, the US economy has steadily improved its productivity for nearly five decades, growing from 45.3 in 1965 to 111.5 in 2010 (see figure 2). This trend makes the decline in ROA even more worrisome. Companies seem unable to capture the benefits of labor productivity for themselves. Instead, cost savings are competed away in an effort to serve more, and more powerful, customers.

However, the headline number alone does not capture the true picture of the forces acting on workers and their implications for companies. Despite improvements in overall worker productivity, exponential technology advances continue to outpace increases in worker productivity. This suggests that firms are falling behind in their ability to use technology to its full potential.14

However, the headline number alone does not capture the true picture of the forces acting on workers and their implications for companies. Despite improvements in overall worker productivity, exponential technology advances continue to outpace increases in worker productivity. This suggests that firms are falling behind in their ability to use technology to its full potential.14

Technological advances have created the richest and most efficient flow and use of information in history. Daily operational tasks such as comparing prices for resource inputs or gathering feedback from consumers no longer require an enormous dedication of human resources. Lower transaction costs for these types of activities within many areas of companies have yielded benefits both in productivity and financial returns, but these improvements capture only a fraction of the potential created by technology.

Workers who learn to continuously upgrade their skills and harness technology will increase their productivity. Those who do not will stagnate. This dynamic creates highly skilled, highly productive workers that are increasingly in demand. Salaries for these high-performing workers will continue to grow, exerting pressure on organizations’ bottom lines. In 2003, “creative” workers, as defined by Richard Florida,15 commanded a $45,500 premium in compensation over the average worker. Over the last 10 years, this compensation gap between creative and average workers has grown to $61,000, increasing nearly 34 percent (see figure 3).16 This is another reason that companies are unable to retain the cost savings that accrue with productivity improvements—creative workers are gaining bargaining power and reaping higher compensation as a result.

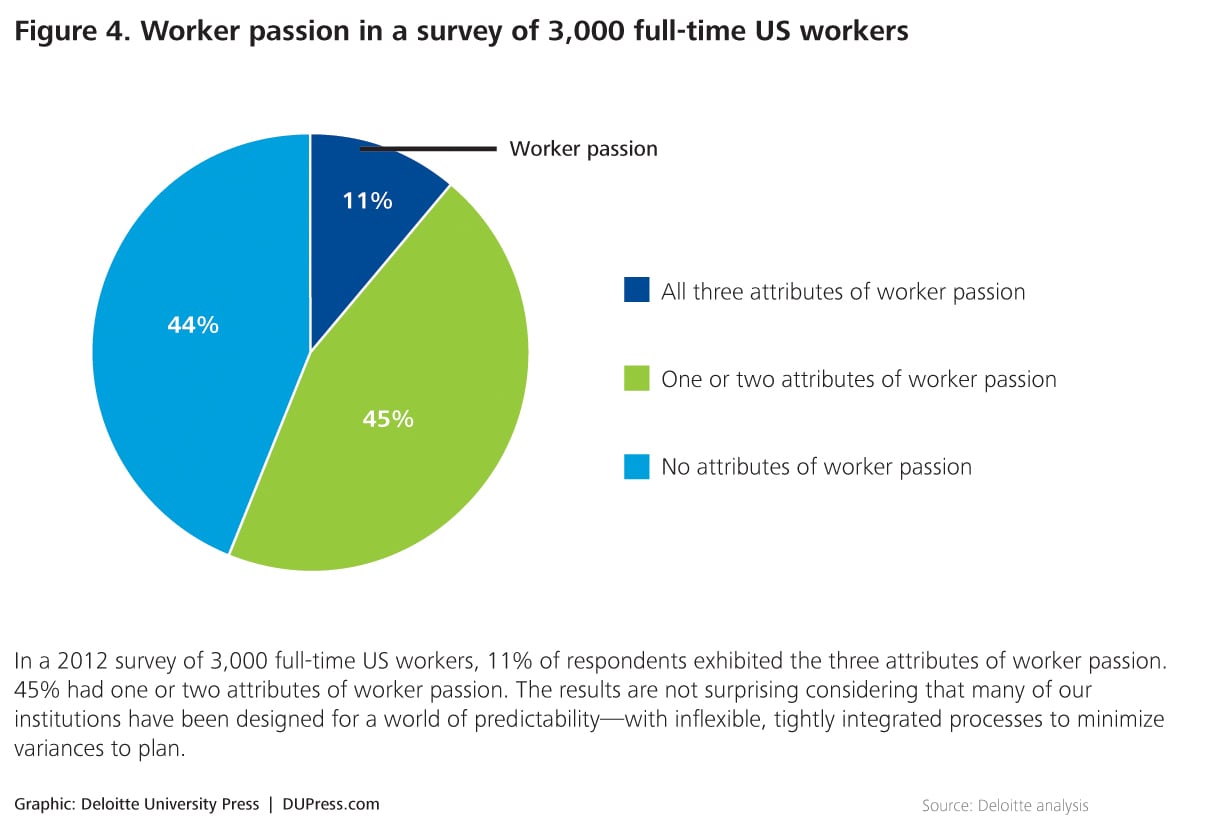

This suggests that more output is being concentrated into a smaller and smaller group of workers. Organizations will expend inordinate time and resources to engage and retain this talent. For example, Yahoo! completed $200 million worth of acquisitions in start-ups to acquire talent to bolster the mobile group.17 Of course, organizations risk a significant loss of productivity if these talented workers leave. Companies have an opportunity to develop more of their workforce to be more skilled and better suited to organizational challenges by creating an environment of continuous learning. Equally importantly, companies will need to find ways to catalyze and amplify passion in the workforce—something that only 11 percent of the US workforce possesses (see figure 4).18 If companies focus on engaging all workers in meaningful ways, the level and size of the talent pool will grow.

This suggests that more output is being concentrated into a smaller and smaller group of workers. Organizations will expend inordinate time and resources to engage and retain this talent. For example, Yahoo! completed $200 million worth of acquisitions in start-ups to acquire talent to bolster the mobile group.17 Of course, organizations risk a significant loss of productivity if these talented workers leave. Companies have an opportunity to develop more of their workforce to be more skilled and better suited to organizational challenges by creating an environment of continuous learning. Equally importantly, companies will need to find ways to catalyze and amplify passion in the workforce—something that only 11 percent of the US workforce possesses (see figure 4).18 If companies focus on engaging all workers in meaningful ways, the level and size of the talent pool will grow.

Paradox 3: Consumers have more selection and, in many cases, lower prices, but companies are still in trouble.

Consumers do have more choices than ever before. The efficient flow of information has allowed latent consumer demands to bubble to the surface and companies to find ways to serve them. US consumers now have multiple choices for virtually every category of product and service. However, consumer choice doesn’t necessarily translate into healthy companies. The proliferation of products and channels is stretching available company resources while increased price transparency puts pressure on margins.

Consider the proliferation of applications available for mobile devices. Since the smartphone came on the scene, the number of apps has grown from the hundreds in 2008 to more than a million. Yet, very few will ever yield a profit, much less a viable business model.19 The value is dubious even when the “app” is used as a portal to other firm products or as part of a product bundle. However, these apps become new channels that must also be served to reach consumers in addition to existing physical and virtual channels.

The automotive industry provides another example of how consumers are benefitting from increased choice and price transparency. Not only are there more car models and more information about car pricing available through a growing array of websites, there is also an increasing number of substitutes to car ownership. Consumers can choose to delay or even forego purchasing a vehicle and take advantage of new ways to access transportation, such as car-shares (Zipcar) and ride-shares (Uber and Lyft).

For firms, the increasing number of channels to serve consumers can lead to a higher cost to serve each customer.

Consumers benefit from increased product selection with lower costs. They compare products online, read reviews, go to the store to interact with the products, and then purchase through whichever channel meets their needs, from lower prices to immediate gratification to personalized service. Marketers have become increasingly sophisticated at reaching these consumers, and consumer spending is at an all-time high.20 For firms, the increasing number of channels to serve consumers can lead to a higher cost to serve each customer. To satisfy an ever-fragmenting consumer base, companies also must continually upgrade and introduce new products. This increases product development costs and compresses product lifecycles. As demanding customers chase the latest offer, more and more money is spent to develop new products that have shorter and shorter lives.

In this environment, companies need close relationships with customers. After all, it’s customers that turn a product or service into economic wealth for the business through their willingness to pay for a perceived benefit. Yet, the pressure to reduce benefits to customers in order to maximize shareholder returns can be immense. Efforts to reduce customer service or remove product features yield cost savings—a short-term boon for companies. However, the ease with which new competitors arise today means new businesses can quickly fill the void if companies fail to balance the evolving needs of customers with the short-term needs of shareholders.

So, here’s the bottom line: Customers are benefiting from trends that increase access to flows of information and enable lower cost production. They are getting more value at lower cost from an expanding array of vendors. For companies, though, this poses a challenge. How will they maintain profitability when customers demand more for less? The long-term decline in ROA suggests that they aren’t, and they will continue to face mounting performance pressures as a result.

Paradox 4: The economy has been growing for years, but companies are still under pressure.

GDP has grown in aggregate over the last 50 years. However, GDP is the absolute measure of consumer spending, business and government investment, and net exports. It is not meant to measure the efficiency or effectiveness of a country in taking inputs and turning them into outputs. Part of the GDP growth has to do with population growth, which leads to more people in the workforce and the consumer base. Other factors that lead to growth include an increase in productivity from both workers and the capital stock businesses use to turn out products, an increase in the size of government, and growing trade with other countries.

The economy has grown over that time period, and it has transformed itself from a mostly product-driven one to include more service-based components. That is, the contribution of knowledge workers and intellectual capital is becoming more important to the performance of our economy. Service economies depend on intellectual capital that is not fully measured in the capital stock of the United States. Economists and policymakers know about this phenomenon, and they are beginning to incorporate the value of these inputs into the capital stock of the economy. From this point of view, the economy has been growing, but we weren’t measuring all of the inputs we use to create that growth.21

GDP is growing in part because companies are delivering so much more value at lower cost to customers. This is good, and it needs to be amplified by effectively tapping into the exponential improvement in technology performance. At the same time, companies must be more creative in finding ways to capture some of the increasing value being delivered to the marketplace.

The question then becomes how best to use the resources at a company’s disposal to create value for its myriad stakeholders. Further, how should companies determine how best to make strategic asset decisions for the future? This requires a deeper exploration of how the very components within companies are being shaped by the forces of the Big Shift.

Exploring Big Shift effects on assets and income

ROA provides a useful framework for understanding how the longer-term forces of the Big Shift are affecting firm performance. At the highest level, assets are growing faster than income. Economy-wide, companies require more assets to generate an equivalent amount of income now than back in 1965. At first glance, this is surprising given the shift toward service industries that are less fixed-asset-intensive and the widespread outsourcing and offshoring of asset-intensive activities like manufacturing and logistics.

What’s going on here? While the difficulty of disaggregating assets consistently across the decades prevents a definitive answer, some broad trends do emerge. Overall, the slowing growth of physical assets—physical plants, equipment, and inventories, for example—is more than offset by the growth in financial assets required to run a business.

The declining importance of physical assets is partially explained by the increasing prevalence of service businesses in the United States over the past several decades. Another factor is the way that digital technology infrastructures enable companies to more easily outsource and offshore asset-intensive businesses; under mounting performance pressure, companies delegate activities to focused providers that can deliver superior performance at lower cost.

But a third factor appears to be at work. Financial assets like cash, intangibles, and accounts receivable increased as a percentage of total assets over this time period. What explains the disproportionate growth in financial assets?

First, rapid growth of the financial sector relative to more traditional manufacturing and service businesses like retailing has changed the economy-wide mix of industries. Some of the growth in financial assets can be explained by growth in the financial sector.

Second, even in more traditional businesses, financial assets appear to be growing as a share of total assets. Much has been written about excess cash, but this increase in cash is partially reflective of companies becoming more risk averse and focused on short-term flexibility. Intangibles have increased, in part, as a function of the increased merger and acquisition activity of companies racing to increase scale and find cost savings. Accounts receivable growth may reflect growing customer power—waiting longer to be paid is part of the cost of doing business when increasingly restless customers feel confident specifying their own terms and conditions.

Across the economy, there has been substantial growth in absolute income, but income as a percentage of revenue has eroded over the decades.

More generally, the upward trend in financial assets seems to reflect a natural tendency to focus on the short term in times of pressure and uncertainty. When the future seems too uncertain to make long-term asset commitments, companies tend to focus more on items like financial assets that they can manage in the short term. While understandable, the long-term deterioration in ROA suggests that this shrinking of time horizons may be counter-productive.

Of course, assets are only part of the equation when it comes to ROA. Investigation into the components of income reveals a more complete picture. Across the economy, there has been substantial growth in absolute income, but income as a percentage of revenue has eroded over the decades. The problem does not appear to be in gross margins. Gross margins have actually increased over time, despite greater customer power. The gross margin increases may be a bit deceiving because they occurred at the same time that the economy was shifting toward service industries where cost of goods sold is less relevant than in product businesses. Higher overall gross margins, therefore, may be partially explained by the mix of businesses over time rather than improvement in the performance of individual companies. In addition, companies may have been able to reduce their cost of goods sold as a percentage of revenue because they, too, are customers to their own suppliers. As customers, companies wield increasing power to squeeze suppliers and extract more cost-savings for themselves.

The improvement in gross margins, however, has been more than offset by rapid growth in other components of income statements as more powerful end customers require more effort to satisfy. The growth of other expense components reflects the more challenging business environment created by the Big Shift and its adverse effect on the operating metrics that drive financial performance. For example, product lifecycle economics have deteriorated in many industries: Companies spend more to develop and introduce products, the products tend to have shorter market relevance, and companies spend more to support them while they are in the market. Similarly, in many industries, customer lifecycle economics have also become more challenging—companies spend more to acquire customers, customers are more likely to defect (higher churn), and companies spend more to serve customers while they have them. Finally, in facility-intensive businesses such as retailing and process manufacturing, companies spend more to add capacity, they tend to generate lower profits over the life of the facility, and the useful life of the facility may be lower as a result of more rapid technological evolution.

As net incomes fail to keep pace with asset growth, companies will continue to struggle to capture opportunities from the Big Shift. Focusing on income statement performance and accumulating financial assets on the balance sheet to manage short-term metrics will only exacerbate this struggle. Instead, executives might consider pulling back to take a long-term view of company performance. The long-term ROA trajectory for a company can be revealing. Digging into the components of ROA and the operating metrics that drive the components that have the biggest impact on long-term financial performance may yield insight into the forces that are reshaping their business environment and allow companies to zero in on the operating metrics that are critical for performance improvement. Rather than simply responding to the latest short-term events in an ad hoc way, executives can begin to focus and prioritize the moves that will really matter in an increasingly challenging business environment.

Thinking in the long term

A company can hit all of its quarterly earnings targets and still not maintain long-term viability. Maximizing shareholder value has translated into focusing only on the short term. Although Warren Buffet famously said, “…our favorite holding period is forever,”22 most shareholders are more focused on investment returns in the short term. Since the 1960s, the average holding period for stocks has dropped from eight years to five days.23

It’s a vicious cycle. Executives are increasingly reluctant to develop and communicate long-term strategic direction given the perception, and often a reality, of greater market uncertainty. In the absence of vision and guidance from company leaders, financial analysts and investors are left with little more than near-term financial results to judge a company’s potential. But as the investment community shifts focus to short-term financial metrics, executives also focus more on these same metrics. This type of self-reinforcing, short-term thinking leads to reactive behavior from management. Companies tend to hedge their bets by deploying resources in multiple areas with the hope that at least one bet will prove fruitful. These types of management practices do not differentiate among short-term events, and they have the tendency to spread resources too thinly. The result is sub-optimal performance on all fronts and failure to achieve longer-term goals or chart a course for long-term viability.

A new mindset is needed. A longer-term view of performance, trajectory, and opportunities can help company leaders prioritize efforts while maintaining a focus on strategic directions and goals. Firms can build strategic conviction based on the macro trends that impact the market and their customers. Rapid prototyping can help companies test the market, as can engaging others in their ecosystems to gather real-time feedback—all while marching toward their long-term strategic goal. This approach can help companies avoid being distracted by the volatility of short-term events.

Paying attention to the trajectory of ROA and the insights it contains can help companies more effectively use their resources to generate returns over the long term. When this shift in mindset occurs, it lends itself to investigating fundamental assumptions of how an organization is structured and what kinds of processes and practices will lead to superior performance. Shifting focus can also help companies develop the resilience and agility required to meet increasing market uncertainty.

Firms can begin to develop a longer-term mindset by looking at their own ROA trajectories over the past 5, 10, or 15 years. ROA analysis is not new. Many executives already look at various cuts of the ROA; however, most of these analyses are short term. For example, the efficiency of a plant’s assets might be analyzed for the past quarter or year. However, very few organizations have the capabilities or incentives to extend analysis beyond this timeframe.

ROA is a lagging indicator. Its trajectory provides insight into the quality of prior decisions and also helps challenge the fundamental assumptions that these decisions were based on. Whether evaluating innovation processes, future opportunities, or current initiatives, companies must question their assumptions, particularly if their ROA has been declining. The following types of questions are paramount: Why do customers develop relationships with our company? How do a company’s products and services meet current and future needs in a truly differentiated way? Why does a company’s talent stay, and how can they be more productive? How can a company get even more leverage by mobilizing complementary capability from other, external participants?

A confluence of factors, including economic volatility, supply and demand shocks, and rapid technology changes are increasingly impacting corporate decision making. For example, when Circuit City was faced with increasing pressure from the rise of e-commerce and the consequent power of consumers, the company made a series of short-term decisions that ultimately decreased their competitiveness. Circuit City’s operating principles were focused around the 5 S's: selection, savings, service, satisfaction, and speed, and the company was profitable between 1997 and 2002. Then, in a series of events to respond to perceived threats, Circuit City sold off its most profitable division in home appliances, discontinued sales commissions, and aggressively expanded its stores in spite of changing consumer preferences to purchase through e-commerce channels. To reduce costs, the company laid off its most experienced, higher-paid workers, replacing them with more junior staff. The result was a significant drop in customer satisfaction. These actions were at odds with its operating principles and diminished the company’s long-term prospects. A sharp decline in performance followed, with ROA decreasing from 3.7 percent to –0.02 percent from 1997 to 2003 as the decisions were implemented.24

Starbucks was able to weather the recession and maintain its long-term strategic vision organized by company principles pertaining to its coffee, partners, customers, stores, neighborhood, and shareholders.25 When Howard Schultz, the former CEO, returned to the company during the recession, he did not focus solely on cutting costs. Instead, he continued to orient the company on its mission involving creating an experience centered on good coffee. The company understood that consumers had more options to explore alternatives in the coffee house experience and worked to reinvigorate consumers' relationship with Starbucks. Starbucks brought in whole beans so that every store ground fresh coffee, committed the company to increasing fair trade coffee purchases, upgraded in-store espresso equipment, and continued to provide health care to all employees.26 Most of these changes required a long-term commitment of assets and a focus on long-term objectives despite a recessionary economy. While Starbucks had a healthy ROA before the recession in 2006 was 13 percent and the company’s ROA rebounded to 15 percent by 2010.27

ROA versus ROE

Return on equity (ROE) is a commonly used measure that attempts to describe how much profit each dollar of stock can generate as opposed to ROA. ROE represents the income generated by the stakeholders’ money. For shareholders, ROE provides a short-hand way of judging profitability of their investments. It is a consolidated view of how well an investment could fare. But the metric’s biggest strength as a summarized view also happens to be its greatest drawback. By focusing primarily on returns generated from equity, the view disregards impacts of leverage. As such, ROE does not provide a comprehensive view of a company’s performance. As a source of financing, debt is an important element of corporate balance sheets. In fact, the amount of total liabilities on companies’ balance sheets has grown 10-fold between 1965 and 2012 (while top-line revenues have grown only 4 times in the same timeframe). While debt can help an organization meet its objectives, excessive amounts can be damaging. These effects, however, are not reflected in ROE as the measure does not directly factor in leverage. If, for instance, an organization were to raise an unhealthy amount of debt but manage to generate income from that debt, ROE would likely rise even though the company may have a riskier capital structure. In this scenario, increased leverage could help a company meet its short-term objectives while threatening its long-term viability given its debt exposure.

ROA provides a more balanced view of profitability compared to traditional metrics. Metrics like ROE disregard risk that financial leverage creates. An increase in leverage commensurately improves asset balances through the cash it provides. Any changes in leverage, therefore, are equally reflected in assets. Another advantage of ROA is its ability to holistically measure business operations. A move to artificially improve net income would create a much smaller change in ROA since the measure weighs net income as a proportion of assets. The choice to compare net income to assets is a significant one. ROA reflects the cumulative outcome of decision making. It gives ROA the benefit of holding management accountable for the cumulative decisions made in deploying assets. If resources are used in projects that consistently yield little value, ROA will stagnate. Alternatively, if management utilizes its assets in projects that more optimally create value, ROA will rise.

Future supply and demand disruptions manifest today through small changes in consumer preferences or continued technological changes to factors of production. The challenge and goal for companies will be to imagine the impact of these signals before they fully play out. The amplifying nature of technology creates a dynamic where these small changes can completely disrupt core businesses in a short amount of time. Yet, this technology can also yield tremendous opportunity to find pathways toward leveraged growth. Latent talent can be accessed on demand. Customer relationships can be deepened through targeted engagement with social media. Both of these examples are tactics in a broader ecosystem approach that can be internalized in any industry. Organizations are currently scaled for ruthless efficiency. The accelerating changes in the marketplace today call for organizations to be nimble and adaptable—organizations that are scaled to learn.

To understand the nature of the current period of uncertainty, we must look beyond the most recent business cycle. Drivers of this uncertainty are rooted in long-term technological changes and public policy shifts that are significantly reducing barriers to entry and movement on a global scale and disrupting every facet of business. Companies must look backward to see how prior decisions have performed and project far enough forward to prepare and capture new opportunities.

Growth in Net income and total assets over time

While media reports tend to focus on the recent growth of absolute corporate income, corporate income does not tell the whole story about a company’s performance. Comparing income to the assets needed to support the business provides a more comprehensive view. While company-wide, corporate net income grew at 3.96 percent compound annual growth rate (CAGR) between 1965 and 2012, total assets grew at 6.38 percent CAGR over the same time period.

Those that can effectively tap into information and knowledge flows create advantages for themselves. Companies that cannot will be at a severe disadvantage as more and more of the US economy moves into knowledge work and service sectors. This doesn’t mean there is no room for products and manufacturing. It’s quite the opposite. The decisions made on each facet of a business, from decisions on how to serve customers to how to organize operations, can be financially tied to asset performance. This is the first signal regarding the fundamental health of a business and the quality of its decision-making processes.

The inability or unwillingness of the business community to adopt this mindset creates an economy where large portions are stagnating with very few consistent winners. Companies that can balance short- and long-term stakeholder needs will be best able to develop a vision and commitment to execution. A long-term focus is inextricably tied to the trajectory of ROA. These companies will be best poised to make outsized gains. Others that fall victim to the tyrannical needs of the short term will continue to be whipped around in an increasingly unstable world. These companies will leave opportunities on the table where more nimble, yet committed, competitors can enter.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.