Corporate development 2011: Scanning the M&A horizon has been saved

Corporate development 2011: Scanning the M&A horizon

01 January 2012

Corporate Development 2011 is Deloitte’s second annual survey of trends in Mergers and Acquisitions (M&A) and Corporate Development. The majority of respondents to our survey continue to be optimistic about the M&A outlook over the next 2 to 5 years and we have started to see more transformational deals—deals focused on transforming organizations in ways that create long-term competitive advantage. While they are often very large acquisitions, they can also be smaller, highly strategic transactions that change the business model of the acquiring company.

Looking out over the horizon—The return of the transformational deals

The profile of deal flow is changing.

The profile of deal flow has changed over the past year or so. In the immediate aftermath of the financial crisis, most companies were preoccupied with liquidity and bolstering their short-term, bottom-line performance in the face of a weak global economy. With investor confidence rising in line with the economic recovery and certain industries such as healthcare, financial services, and technology undergoing unprecedented change, we are seeing a shift in focus to a long-term growth orientation. As a result, the volume of transformational deals—deals with the potential to fundamentally transform the acquirer’s business model and create a sustainable competitive advantage—has increased. To the extent that transformational deals are correlated with size, there were 28 deals over $1 billion in the first quarter of 2011 compared with 17 during the first quarter of 2010.1

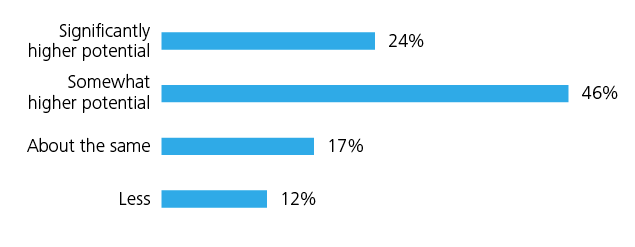

From an M&A perspective, executives are looking further into the future and considering deals that have the potential to create a sustained competitive advantage. Half of the professionals surveyed expect the number of transformational deals to increase in the next two to five years (see figure 1). Additionally, a vast majority (70%) see a somewhat higher to significantly higher potential for greater risk-adjusted rewards from transformational deals (see figure 2). While transformational deals are increasing in frequency and are perceived to have a higher risk-adjusted reward ratio than deals closer to the core business, they are generally more complex and challenging to execute. Accordingly, Corporate Development teams may need to revisit their team complement, deal process, governance, tools, and methodologies to drive value from transformational deals.

Figure 1. Transformational deal volume over the next 2-5 years

Figure 2. Likelihood of transformational deals to present greater risk-adjusted rewards than deals closer to the core business

Challenges and the role of Corporate Development.

There are many obvious challenges associated with transformational deals. According to survey respondents, the top concern is the impact of the deal on the customer value proposition (see figure 3). Transformational deals often require refining the customer and product value proposition, and this subsequently needs to be systematized throughout the entire organization of supporting processes, metrics, infrastructure, capabilities, and skills. “Doing this becomes a significant task in coordinating program management and alignment between traditionally siloed functions. This is often where the traditional integration strategies, which are more oriented to functionally driven assimilation of a target, begin to break down. Supporting this, we have observed that organizations that fare better in transformational deals are those with clarity and broad executive buy-in to a well-articulated and detailed vision—which is often driven by a detailed customer experience vision—and those that drive rigorous and centrally-led integration programs with clear, broad executive accountability for both the integration process as well as the results,” says Marco Sguazzin, principal with Deloitte Consulting LLP and a post-merger integration specialist.

It should go without saying that in transforming a business, everything needs to support that—including how the deal is executed and how the companies are integrated—and all of it needs to be done at the same time and while running the business. The glue that essentially holds it all together is a company’s Corporate Development team because of the need to maintain an overall view of the entire transformational program. Corporate Development teams are usually the best equipped, with the growing recognition that those teams need people with a broad range of skill sets, to look across all aspects of a deal and to find and liberate value as the sources of value change.

Figure 3. Most challenging aspects of change for a transformational deal

We also probed the question of whether the role of Corporate Development changes in transformational deals and, if so, how. A number of survey respondents indicate that many of their responsibilities stay the same irrespective of the type of deal. However, a meaningful percentage (44%) report that they take on an increased level of responsibility for facilitating executive alignment in transformational deals, and 42% report that their level of responsibility for leading transformational deals increases (see figure 4). In other words, the critical role played by Corporate Development in acting as the glue that builds alignment across the organization takes on heightened importance. This is in keeping with what we have heard from Corporate Development executives in terms of key team member skill sets that they regard as increasingly valuable, with higher import given to professionals who can work comfortably across businesses, functions, and geographies (especially in matrixed organizations), communicate effectively, influence people, and build alignment around business and transaction objectives.

Critical success factors and the role of Corporate Development.

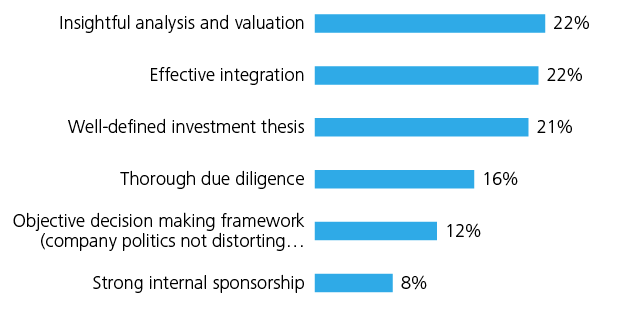

In terms of how most transformational deals fare in achieving expected objectives, a minority (31%) of survey respondents said there is significant alignment of value drivers 12 to 18 months after a transformational deal they were involved with closed (see figure 5). The top three reasons, in descending order, reported by respondents as to why transformational deals met or exceeded expectations are insightful analysis and valuation, effective integration, and a well-defined investment thesis (see figure 6).

Figure 4. Difference in responsibilities between transformational deals and those closer to the core business

Figure 5. Alignment of value drivers 12 to 18 months after close of a transformational deal

Figure 6. Primary reason transformational deals meet or exceed expectations

Clear investment thesis.

Leading practice suggests that all deals should start with a well-defined investment thesis laying out the business purpose for doing the deal. This encourages executive and deal team alignment on key value drivers and also provides a clear basis for communicating the merits of the deal to stakeholders. “On transformational deals, this can be more difficult because the value drivers are oftentimes less obvious, which makes having a clear investment thesis even more important,” says Steve Joiner, partner with Deloitte & Touche LLP, and a Transaction Services leader. Starting with a well-defined investment thesis also focuses due diligence more on analysis of forward-looking elements of the newly-defined business model rather than historic operating performance.

Insightful analysis and valuation.

In transformational deals, relying on the past as a prologue to the future can be dangerous, since the goal of a transformational deal is to transform the combined enterprise so that it ultimately emerges as a more formidable competitor. Therefore, it is no surprise that over 40% of survey respondents report that Corporate Development puts much greater emphasis on analyzing and validating the key value drivers of transformational deals (see figure 4). Doing this requires an amalgam of skill sets as well as viewpoints—broad industry insight, business strategy, sales and marketing, operations, finance, etc.—often in an environment where the deal team does not have the luxury of access to a full array of talent because of confidentiality concerns. This can place additional stress on Corporate Development to stretch beyond its traditional comfort zone and may be the reason we are seeing a trend toward more diversification of deal team talent. Deal teams are also leveraging tools and techniques such as game boarding, scenario planning, and decision analysis to add forward-looking industry and competitor scenarios, strategic flexibility, objectivity, structure, and insight into their analysis and decision-making process.

Corporate Development professionals who have recently announced transformational deals indicate that their role in valuation went beyond simply running DCFs and looking at market comparables. They worked side-by-side with executive management and advisors in crafting comprehensive business plans and testing the strategies of the combined companies. They also spent more time with target management, as appropriate given regulatory limitations, shaping their shared vision of the future and testing alternative business models to help maximize the value of the combined company.

Increased role in integration.

A number of survey respondents (31%) also report that the Corporate Development team’s role in coordinating the integration process increases for transformational deals, reflecting the importance of managing change through the combined organizations in a seamless way (see figure 4). A number of survey respondents indicated that commencing integration planning during due diligence is a key factor in positioning the combined companies for success, as this is the time when practical business to models and integration scenarios are truly able to influence the investment thesis and vision, synergy estimates, executive buy-in, and even valuation models. The level of pre-close and even pre-announcement integration planning in transformational deals is sometimes limited because of competitive sensitivities and lengthy regulatory reviews. To overcome these practical limitations, accelerate integration, and even optimize synergies or reduce risk, skilled acquirers are using smaller and more visionary teams in the pre-announcement phase. They are also using advanced techniques such as clean rooms during the pre-close phase where detailed integration planning can take place without running afoul of competition law or broadly divulging highly confidential information. This translates to a larger opportunity for Corporate Development to shape the strategic options and to facilitate broader executive buy-in. Additionally, Corporate Development is able to dive deeper into the actual integration planning process with the goal of aligning all plans with a changing enterprise vision and ensuring that the deal value drivers are enabled by every function within the business. When industry conditions change, Corporate Development is often the most effective in facilitating a rapid review of direction and any resulting response that may be used to defend or exploit new opportunities that arise.

Decision-making authority.

This increased responsibility and heightened importance of the Corporate Development function with transformational deals does not necessarily come with a greater level of decision-making authority. As the survey results indicate, 22% of respondents report that their level of decision-making authority actually decreases in transformational deals, as executive management and the board take on a higher level of direct participation and oversight (see figure 4). This implies that Corporate Development teams may, therefore, need to exert more effort to create alignment across the organization, which may require different tactics. We are curious to observe whether this changes over time, since survey respondents indicate that 49% of Corporate Development heads now report directly to the CEO (see figure 15). This is negatively correlated with company size though, with about 65% of Corporate Development heads from companies with $250 million or less in revenue reporting directly to the CEO but less than a third doing so for companies with $5 billion or more in sales.

Valuation is a team sport—Are you asking the right questions?

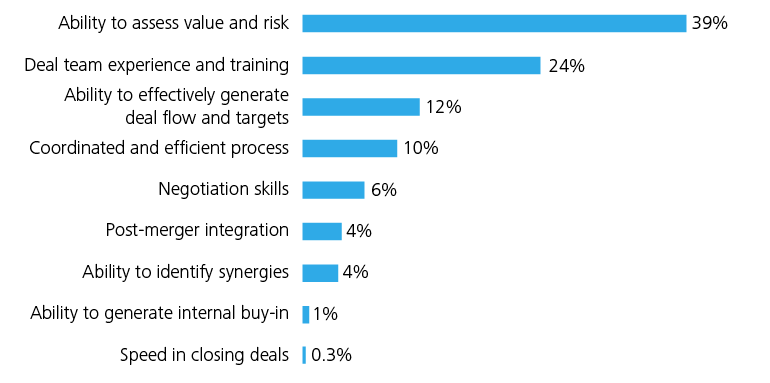

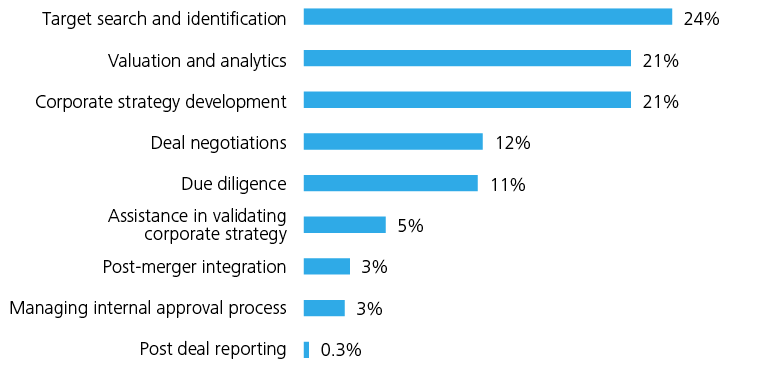

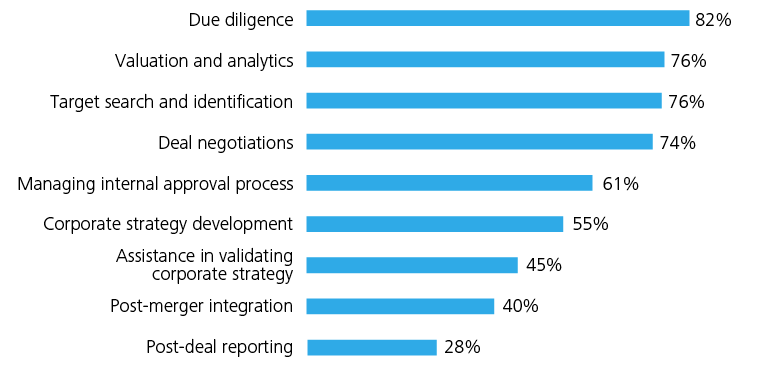

Value and risk assessment capabilities continue to be the most important skill set of Corporate Development teams, according to survey respondents (see figure 7). After target search and identification, valuation and analytics is the most value-added service provided by Corporate Development (see figure 8). In fact, 76% of respondents say their Corporate Development group has primary responsibility for valuation and analytics (see figure 9). This raises the question of what analytical approaches are being applied by Corporate Development teams to understand value, and whether they are periodically reassessing their methods to allow for more dynamic tools that can add insight into deal decisions.

Figure 7. Most important skills for Corporate Development effectiveness

Figure 8. Most value-added Corporate Development group services

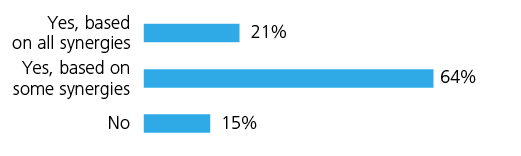

Respondents report that the most important valuation criteria considered when making M&A investment decisions are NPV, ROI, or IRR, with nearly 42% of respondents choosing those factors as the most important evaluation criteria (see figure 10). Asked why many deals fail to meet expectations, respondents cite such reasons as overly optimistic forecasts, unreasonable expectations in valuation, models that are too aggressive, markets changing faster than expected, overly optimistic plans that run into competitive marketplaces, and reality versus diligence findings. On the other hand, regarding why deals meet or exceed expectations, several respondents indicate that it is because they rely on conservative projections or because, in competitive auctions, the majority of respondents (64%) only consider the value of certain synergies when determining their offer price (see figure 11).

Figure 9. Primary responsibilities of Corporate Development group

Taking a deeper look at what respondents cited as the reason for disappointing deal outcomes, it is important to consider the root cause of what respondents indicate is faulty forecasts and deal models—that these tools are all operated by people. So perhaps the issue is not what tools were used, but how the analysis was conducted. Too often, we observe that not enough time is spent framing an investment thesis or identifying and analyzing the potential risks and opportunities using a Corporate Development team’s broad perspective before getting started. Additionally, it is easy to get caught up in trying to comply with a diligence checklist or form rather than thinking through the big-picture, long-term issues that may come about. Executives need to be adept at avoiding the central tendency bias—instead of remaining anchored around a base case, the inherent risks and opportunities of each specific deal also need to be evaluated. Another inherent challenge is that Corporate Development and other company executives involved in deal modeling are people too, and people tend toward what is familiar and comfortable. This means that many valuation models show great detail around topics that are familiar—for example, cost structure—but not enough detail around factors that are unfamiliar, for example, revenue assumptions, competitive response, or regulatory change, which may have profound consequences on value. Although there are tools and methodologies to add insight into uncertainty analysis, including multi-attribute decision modeling, we would not describe these approaches as being in common practice, and discounted cash flow continues to be the preferred modeling framework. However, our sense is that acquirers recognize the limits of discounted cash flow and are seeking dynamic modeling alternatives.

Figure 10. Most important evaluation criteria when making M&A investment decisions

Figure 11. Value of expected synergies considered in competitive auction offer price

We commonly see executives enter negotiations with preconceived notions. To overcome these challenges, acquirers can start by asking the right questions in the right way. In other words, ask how assumptions can be wrong rather than just reasserting what is known. An example, imagine a newspaper headline dated three years from now that reports terrible news for your deal. What might have happened to create this headline? What actions could have been taken to protect the transaction results? Conversely, if the headline is excellent, how did that occur? What could have been done to capitalize on it? “Framing the uncertainties in a deal is much more effective if the starting point begins with asking the tough questions about extreme risk and opportunity rather than just reinforcing the base case assumptions,” says Charles Alsdorf, director with Deloitte Financial Advisory Services LLP, and the leader of the Capital Efficiency practice.

Corporate Development also needs to harness the knowledge within its four walls. Before starting the deal model, it is important to have multiple people in a room who can speak to different scenarios and break down the drivers of value and risk. Time and again, the deal analysis and valuation exercises are done in isolation, without input from the range of specialists inside the company. Sometimes this is because deal teams are limited because of confidentiality considerations, but, more often than not, because the right people with the right knowledge are not engaged in the process.

Circling back to respondents’ comments that deals fail because it is difficult to anticipate changes in the marketplace, it is, of course, impossible to predict the future. However, a thoughtful team approach that considers a broad range of future scenarios, both favorable and unfavorable, should enable the identification and analysis of most of the potential uncertainties underpinning any given deal.

Beyond hurdle rates—To the portfolio!

When we asked survey respondents what they give more weight to in evaluating the effectiveness of their Corporate Development activities, the majority (69%) said performance on a deal-by-deal basis, rather than performance across a portfolio of deals (see figure 12). At the same time, respondents reported that corporate strategy development is one of the top three most value-added services provided by the Corporate Development team (see figure 8). This suggests that Corporate Development’s responsibilities continue to move beyond execution further upstream into strategy. Given this trend, what role can Corporate Development play in linking into an enterprise’s capital deployment decision framework and how might that role change in the future?

Most Corporate Development groups do not get involved in determining how capital is allocated across the full range of a company’s investment alternatives (e.g., M&A, organic growth, share repurchases). When it comes to Corporate Development’s stewardship over capital allocation, it seems that in most companies, it is limited to evaluating whether any particular deal has the potential to earn a return in excess of its cost of capital since NPV, IRR, and ROI rank high on the list of the most important evaluation criteria considered when making M&A investment decisions (see figure 10).

Figure 12. Relative importance in evaluating Corporate Development effectiveness

Only 31% of Corporate Development groups evaluate performance across a portfolio of deals (see figure 12). This indicates that most companies that grow through acquisitions build brick-by-brick and may not be giving full consideration to the benefits or interdependencies that one deal has on another. For example, a series of acquisitions that leads to a better overall customer experience could have the potential to create more value for shareholders than a one-off deal. Portfolio analytics assist in identifying and measuring interdependencies across investments. Supercharging Corporate Development’s analytical toolset could allow it to consider the additive benefits of transactions and the true aggregate impact on shareholder value and strategic impact.

A deal-by-deal assessment also does not address the question of how to maximize total return to shareholders nor does it necessarily capture the full contribution that the Corporate Development team makes to the success of the enterprise. Just because a deal has the potential to earn a return in excess of the company’s cost of capital does not mean that shareholder value is being optimized. Similar to taking a portfolio view of M&A investments, there is an opportunity to use portfolio analytics such as decision analysis to compare a broader range of investment opportunities across the organization. While we increasingly see new analytical approaches creeping into the assessment of investment decisions, especially within a particular business area—e.g. using decision analysis to prioritize a portfolio of R&D projects—rarely do we see them utilized across a company’s entire portfolio of investment decisions.

Based on last year’s survey results, it is clear that there is increasing pressure on companies to accelerate growth through acquisition, with the majority of respondents indicating that they expected M&A to add 5% to top-line growth on a compound annual basis over the next two to five years.2 Corporate Development plays a key role in driving that performance and we observe that it is becoming more common for Corporate Development teams to get involved in “special projects” to support their company’s growth objectives. Corporate Development’s skill in assessing expected risk-adjusted returns from M&A transactions as compared to alternative investment opportunities not only helps a company use M&A as a competitive differentiator, but may also enhance capital efficiency across the organization. The Corporate Development team, with an increased focus on strategy and deep analytical capabilities, may be perfectly suited to lead this next-generation approach to capital deployment.

The X factor—Talent

Respondents were also asked about where they source their Corporate Development talent. Forty-two percent state that their main source for Corporate Development talent is internal (42%), followed by experienced hires (25%), and former investment bankers (see figure 13). We observe that sourcing qualified talent from traditional sources is becoming more challenging as Corporate Development teams expand internationally.

Typically, Corporate Development focuses more on up-to-the-deal closing activities and less on post-merger integration. According to Orlan Boston, principal with Deloitte Consulting LLP and a post-merger integration specialist, “Integration is becoming more and more important as Corporate Development professionals are playing more leading roles on integration for the sake of continuity between pre-deal and post-deal activities.” Accordingly, some Corporate Development groups are now making sure that abilities within their respective teams cover all functions to reflect a variety of skills and experience that collectively can be used to best manage deals. This echoes what we see with valuation at the beginning of a deal—that it is crucial for Corporate Development teams to harness the knowledge within their organizations.

Respondents report that the ability to assess value and risk is the most important skill regarding what contributes most to the effectiveness of Corporate Development, followed by deal team experience and training, and the ability to generate deal flow and targets. If we think about this in conjunction with what survey respondents reported about why deals succeed and fail, it supports the need for an experienced team that is able to measure value, think strategically long-term, and perform their due diligence to foster successful integration. This relatively new emphasis on both pre- and post-merger integration underlines what the previous year’s survey also touched on—that the responsibilities of Corporate Development teams have moved beyond a purely execution-driven approach.

Figure 13. Corporate Development talent sources

Figure 14. Next step in career progression for Corporate Development team members

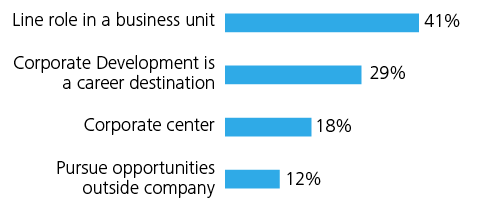

In terms of the next steps in career progression for Corporate Development team members, 41% of the respondents cite a line role in a business unit (see figure 14). The second highest response is that Corporate Development is a career destination (29%), followed by corporate center (18%). The lack of a clear-cut majority response suggests an absence of a well-defined career path for Corporate Development. While there is a positive aspect to having a fresh perspective every couple of years or so in the Corporate Development function, our takeaway is that a more deliberate career path plan for the Corporate Development function would enhance the function’s ability to attract and retain talent.

Nearly half of all respondents note that their heads of Corporate Development report to the CEO and 28% say the head reports to the CFO (see figure 15). This may reflect the increasing strategic importance of Corporate Development and how it helps the business to function and set strategy. It should be noted though that the focus of a given Corporate Development team dictates the structure and types of capabilities sought after in each group. For example, Corporate Development teams within highly acquisitive companies may have more of an internal strategy group structure and may value deal and integration expertise more than companies that are not as acquisitive.

Most respondents report that the average tenure of Corporate Development members is in the two-to four-year range (see figure 16). Perhaps this is because companies are increasingly recognizing the need to disperse talent. With salaries in Corporate Development generally less than those in investment banking—40% of respondents say that the average annual compensation for members of their Corporate Development group is between $100,000 and $175,000—some companies are even using Corporate Development as a rotational program of sorts for high performers to obtain broad exposure to senior executives, to gain a broader understanding of the business, and to ultimately move up and fulfill different types of roles within the company (see figure 17).

Figure 15. Person to whom the head of Corporate Development reports

Figure 16. Average tenure of Corporate Development group members

Figure 17. Average compensation of Corporate Development team members

Seeing through the mist—The blurring lines between stages of the deal process

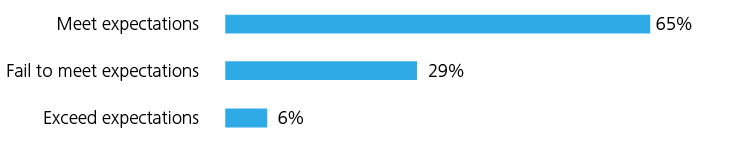

Sixty-five percent of the survey participants indicated that in their experience, most deals meet or exceed expectations (see figure 18). Although there are many studies that conclude that most deals fail to meet expectations, there is a fair amount of debate surrounding how success or failure is defined. Instead of deliberating on this point, we prefer to focus on those characteristics that lead to success, recognizing that there is no single factor and that a good deal requires careful orchestration of multiple components in which Corporate Development plays a key role.

When we asked survey respondents the primary reason why deals meet expectations, a number of respondents referred to a combination of due diligence, valuation, and integration as a system rather than as separate activities. It is interesting to note, however, that 82% and 78% of respondents indicate that Corporate Development has primary responsibility for due diligence, and valuation and analytics, respectively, but only 40% say it has primary responsibility for integration (see figure 9). This indicates why it may be a challenge to maintain alignment and coordination as deals pass from one phase to the next and as primary responsibility for that phase of the deal passes from one team to the next.

On the flip side, survey respondents cite poor due diligence, unrealistic expectations, and poor integration as some of the most common reasons deals fail to meet expectations. Due diligence is important since it is the process through which information is identified and analyzed for purposes of valuing the target. It can also set the stage for the identification of potential synergies and an expeditious integration of the target. These responses tend to oversimplify the reasons for deals failing to meet expectations since the causes are much more nuanced. For example, poor due diligence, cited by a number of respondents, can be caused by many factors such as an inexperienced deal team that does not have the skill to properly interpret diligence findings or poor deal team coordination that does not get the right information to the right stakeholder at the right time, or an inadequate scope that does not consider key risk factors.

Figure 18. Deal success rate

It has become common practice for acquirers to conduct commercial, operational, legal, and financial due diligence prior to an acquisition. However, in the past, this analysis rarely extended to the evaluation of post-transaction operations vital to unlocking the potential value from a deal. There was often a clear delineation between deal and integration teams. In contrast, today, survey respondents indicate that the lines between pre- and post-transaction continue to blur and that Corporate Development is taking on additional responsibility for integration. We are also seeing Corporate Development teams being held accountable for the results of deals they led for longer periods of time after closing, in some cases for as long as two to three years.

As the line between pre- and post-transaction blurs, more is being demanded of Corporate Development teams in the due diligence and valuation process since they can help set the stage early on for successful integration. In many companies, Corporate Development has become adept at accessing capabilities for deeper and more insightful analysis throughout the deal process. Valuation is now diving deeper into what drives value and risk and how these factors behave under changing conditions. Increasingly, the insights gleaned through the due diligence and valuation process pre closing are being used to inform and focus Day 1 operating plans to increase the probability of realizing the expected value of the deal postclosing. For these reasons, Corporate Development may need to become more adept and team more effectively with business units and functional leaders involved in a transaction to effectively model different scenarios for value creation and risk from the deal.

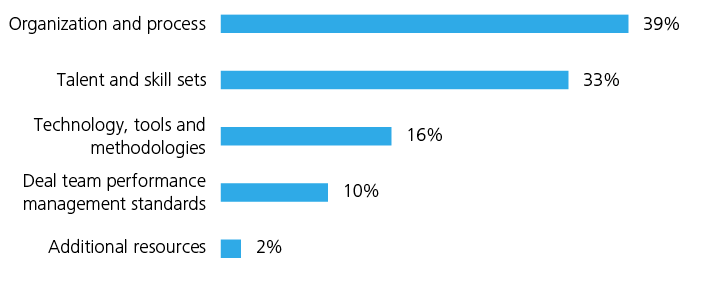

Effective diligence informs valuation, which, in turn, allows management to create a roadmap to help facilitate smooth integration of a target and value capture. Consistent with the results of last year’s survey, respondents indicate that the greatest opportunity for improving the effectiveness of their Corporate Development group is through improvements in organization and process (see figure 19). This underscores the importance of being able to deliberately move through the deal process in a coordinated fashion, with each stage building on the learnings of the prior stage. We expect to continue to see the role of Corporate Development expand beyond execution and for playbooks, project and knowledge management tools, reporting templates, and methodologies to continue to creep into the standard toolbox of the Corporate Development team.

Figure 19. Greatest opportunity for improving Corporate Development effectiveness

Pack your suitcase—The world continues to get flatter

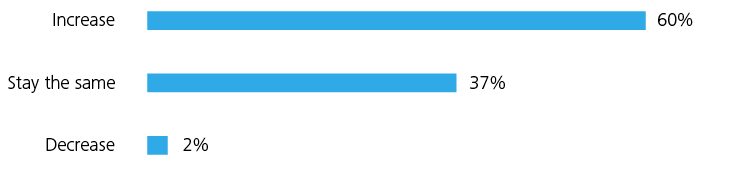

As the survey results indicate, most respondents (60%) expect the number of deals their companies pursue to increase in the next two to five years (see figure 20). Increasingly, deal flow has become cross-border as companies pursue opportunities in markets that present higher growth opportunities than their home markets. Cross-border M&A increased 71% to $800 billion in 2010 from $469 billion in 2009, representing 38% of the total global deal activity.3

For a variety of reasons—including globalization of sourcing and customer relationships, the availability of qualified lower-cost labor, and other market advantages such as free trade agreements and tax treaties—cross-border deals have become increasingly attractive to companies of all sizes. In the past, the volume of cross-border deals was more heavily weighted toward large multi-national companies, with both buyer and seller originating from developed countries. The paradigm has shifted and companies of all sizes are considering acquisitions across geographies, with a particular focus on high-growth BRIC countries (Brazil, Russia, India, China).

Culture and process.

Cultural differences can present practical challenges in the deal process for Corporate Development teams. It is advisable to engage with local managers and advisors who can provide guidance about the cultural norms in dealmaking early in the process. For example, detailed due diligence request lists that are common in western countries may be misinterpreted in certain non-western countries as a lack of trust by the target company’s management. Therefore, seeking advice about how to manage communication with the target is critical and can make all the difference in creating a productive dealmaking environment.

According to survey respondents, target search and identification is one of the two most value-added services provided by Corporate Development groups (see figure 8). Cultivating relationships in cross-border deals is a critical and sometimes time-consuming responsibility. “Careful consideration needs to be paid to the relationship with the seller and how this is managed. Different cultures have different expectations, and this can result in the requirement for more face-to-face interaction than parties may be accustomed to. It is not uncommon, especially in emerging markets, for parties to expect that senior management will be involved extensively along the way,” says Will Frame, managing director with Deloitte Corporate Finance LLC. It is important for buyers and sellers to set clear expectations early in the deal process about the level of senior management involvement to make efficient use of their time and to avoid misunderstandings.

Figure 20. Average number of deals pursued over the next 2-5 years

We also observe that cross-border deals often have larger deal teams, as the head office and local managers move up the learning curve. This can lead to higher transaction costs. Experienced cross-border dealmakers also recognize that more attention needs to be paid to managing communications within the deal team. Larger deal teams require more careful orchestration and definition of roles and responsibilities. Project management tools to keep teams focused and executive dashboards to keep home office management apprised of deal progress are becoming more common to assist the team efficiently.

Due diligence.

A majority (82%) of survey respondents indicate that their Corporate Development group has primary responsibility for due diligence (see figure 9). Given that responsibility, and the challenges presented by international transactions, Corporate Development teams need to assess whether their playbooks address these challenges. Due diligence in emerging markets can be complicated because data sources can be incomplete or unreliable and high-quality financial and operating data can be scarce. Additionally, historic financial and operating data may not be a good basis on which to forecast future results, especially when a target will be materially transformed or when the deal involves a state-owned enterprise. To overcome the garbage-in, garbage-out problem, companies are increasingly relying on alternative methods to improve the reliability of information. This may include “audits” of financial information, background investigations of vendors and other business partners, and more thorough commercial due diligence to better understand the local market environment. Commercial diligence tends to be more grassroots and can entail customer interviews, a holistic “walk-through” of the supply chain, face-to-face meetings with regulators, and delving into the key operational and market conditions expected to drive value.

Corporate Development teams are also expanding their universe of advisors to include local country advisors—such as former local industry executives or regulators—and investigators who can add insight into the quality of information and sustainability of cash flows of the target company during their dealmaking deliberations. Corporate Development professionals also report that their normal diligence process is expanding to encompass a broader range of cross-border regulatory issues that can impact maintainable earnings and deal pricing such as the target’s compliance with the requirements of the Foreign Corrupt Practice Act (FCPA) and UK Anti-Bribery Act, Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) sanctions, and Anti-Money Laundering controls.

Profile of survey respondents

Deloitte conducted a survey of professionals involved in Corporate Development decisions at their organizations. The survey was conducted online from March 28 to April 25, 2011, and was completed by 325 respondents.

Twenty percent described themselves as Head of Corporate Development at the company, business unit, or subsidiary level. Another 22% of respondents were Corporate Development executives, while 21% were staff. In addition, 8% of respondents were CEOs or presidents and 8% were CFOs (see figure 21).

Twenty-eight percent of the professionals surveyed were from companies with annual revenues of over $5 billion, with 26% having revenues of $1 billion to $5 billion (see figure 22). The remaining respondents were from companies with revenues less than $1 billion. There was strong representation from both public companies (60%) and private companies (40%).

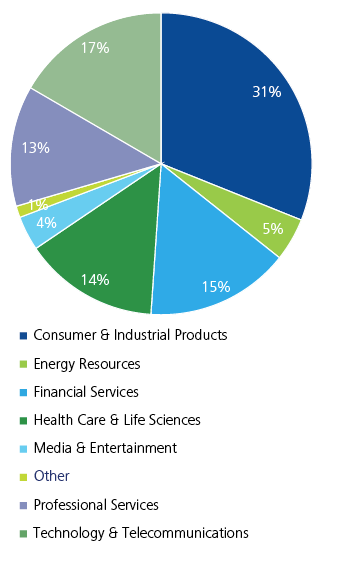

Respondents belonged to a wide cross-section of industries (see figure 23) and there was a fairly even distribution in terms of geographic distribution, with the companies having operations in anywhere from one to over 50 countries (see figure 24).

Figure 21. Role

Figure 22. Annual revenue

Figure 23. Primary industry

Figure 24. Geographic dispersion

Perspectives

Stan Bergman

Chairman and Chief Executive Officer, Henry Schein, Inc.

As CEO of a Fortune 300 company and the largest provider of health care products and services to office-based dental, medical, and animal health practitioners, what do you expect from your Corporate Development team?

Henry Schein’s executive vice president of corporate business development has three areas of responsibility: acquisitions, strategic planning, and global supplier partner relations. At Henry Schein, corporate business development transcends the transaction. Our corporate business development team must completely understand the dynamics of the businesses, closing the deals, and advising our business units involved in the transactions.

Our corporate business development team also remains involved for some time after the closing, working closely with each of our business units to help grow the respective businesses. The corporate business development team is intimately involved in our business units’ strategic planning process, and actively participates in monthly executive committee meetings.

Corporate business development is integral to Henry Schein’s success. Since becoming a public company in 1995, consolidation of our markets has been one of our strategic goals, so we expect to close a certain number of accretive transactions each year. Our corporate business development team has successfully completed more than 200 transactions during this time period.

How do you hold the team accountable for delivering the expected results of a deal?

First, our corporate business development team’s compensation is dependent upon its success. Corporate business development helps to shape each deal and is responsible for the results of the transaction for the subsequent three years. This means that the success of our corporate business development team is measured well beyond the close of the deal.

Second, involved in every deal is an integration team, comprising professionals from key areas within our company. Typically our integration team members are engaged full-time in mergers and integrations. This team is operationally driven and familiar with the infrastructure areas within the company.

Third, Henry Schein’s culture empowers Team Schein members and encourages success. Nothing breeds success better than a cohesive, empowered, and motivated team.

What are the critical success factors for acquiring and integrating targets?

Ultimately the most important part of any deal is people. Of course, strategies must be aligned, models must be developed, and all relative areas of our business must be consulted about our models and assumptions. But it comes down to ensuring that we have aligned the interests and expectations of the people selling the company with the interests and expectations of those who will operate the business after the acquisition. Everyone should know the role that he or she will play after the acquisition is completed. We also want people to understand that if there are redundant positions, the situation will be handled properly. More importantly, once everything has been resolved, we want everyone to know that they are on the winning team. It all comes down to people—doing the necessary work in advance and executing those plans well.

How do you maintain your customer-centric focus in the heat of a deal?

That is the challenge. A very small acquisition does not really impact the overall business, so it is business as usual for us to provide customers with the best service possible. However, when there is a complete restructuring of a business following a large acquisition, we must be inwardly focused for a while. For example, the creation of Butler Schein Animal Health combined the number one player in this market with three other leading players, merged 15 warehouses, moved the businesses onto a new software platform, and developed a new management structure, compensation program, and brand. For the first year after the deal, we were driven operationally to ensure the business was managed properly, and we did not devote a great deal of time to seeking new business during that period. Now that the acquired business has been integrated onto our platform, we are focused on building the business. It also was critical to align the sales force to ensure that each sales representative knew what was in it for them. If the needs of the sales force are not addressed on the day the transaction is announced, the very next day the sales force will go off to the competition.

How do you ensure that deals deliver expected results?

From my perspective, it is essential to understand the deal and integration plan well in advance, so we know what is expected of people and can ensure that those expectations are understood by everyone involved. At Henry Schein, every deal goes to an internal investment committee for approval, and we make sure that the right questions are asked so that everyone is on the same page. We also expect regular updates from the corporate business development and integration teams, either at our monthly executive committee meetings in the case of smaller transactions, or more frequently for larger deals.

How do you get the right alignment so people joining Henry Schein hit the ground running?

Many of the businesses we acquire were started by entrepreneurs, who are frequently challenged to become part of a team in a Fortune 300 company, but we have a formula that overcomes that. The key is to keep the newly acquired management team engaged. If we can continue to engage our entrepreneurially driven talent to provide unique and innovative ways to serve our customers, then we retain an important advantage over our competition.

We appoint a CFO who can interface between our corporation and the management of the acquired business, as well as human resources representatives who ensure the new management team understands our needs from a Team Schein perspective. Then we link key leaders from the acquired company or joint venture with the right people at Henry Schein, whether it is in sales, marketing, operational, IT, or other areas. It comes down to involving the key people during the acquisition period—from the legal team performing due diligence to those on the contract side of the transaction, to our M&A team—so that the day we close, everyone knows their respective roles and can hit the ground running.

Perspectives

Dayan Abeyaratne

Vice President, Corporate Strategy & Development Constellation Energy

As a Fortune 500 energy company, what is your Corporate Development team’s role during a deal?

Typically, this will vary based on the type of transaction. For example, in an asset deal such as Boston Gen, our team will own every aspect of the transaction, including origination, execution, and sponsorship through the approval process. In contrast, while we would still play an integral role in every aspect of larger transformational deals like the pending Constellation-Exelon merger, a large part of the actual negotiation often is, and should be, done at the Chairman/CEO level, given these transactions are as much about formulating a shared vision at the very top and managing a successful integration as they are about easily quantifiable economics.

Coming from a banking background, what surprised you as you went through various deal processes on the client side?

I think the greatest surprise for me has been the depth and breadth of consideration that goes into any principal investment decision in general. For example, I was surprised by the vast array of issues—from regulatory considerations to employee matters—that need to be considered in depth and resolved by senior management to ensure the successful execution of a transformational transaction such as Exelon. On the other hand, I was also surprised at the level of detailed analysis that goes into the commercial due diligence on an asset deal such as Boston Gen where every contract and nuance that affects value has to be carefully considered when you are actually going to be owning something. In short, I think that while the bankers often work very hard on deals, many do not have a full appreciation for just how hard the client is working, especially at the senior management levels.

What do you consider when assessing whether a deal is good for the company?

It almost goes without saying but the key consideration in any transaction should be its impact on shareholder value. That said, one must never underestimate the importance of regulatory and other broader concerns surrounding a deal, not only in terms of how these affect the certainty of closing and realization of shareholder value in general, but also in terms of overall implications of a deal on our broader stakeholders in general. We in the energy industry are particularly well-schooled in thinking through these issues but I think my colleagues in other sectors will readily acknowledge the significance of these factors as well.

When do you typically flesh out the investment thesis of a deal?

As a rule, the investment thesis should become apparent in the very early stages of the game or you should probably think about moving onto something different. On the proposed Exelon merger, the strategic rationale incorporated a myriad of benefits to both companies, including two very complementary business models and service territories; increased scale and scope; and greater regulatory, geographic, and fuel source diversity.

How would you contrast the negotiation process on an asset deal to that of a transformational stock for stock merger?

While everybody is eventually a repeat player in the M&A game, asset deals for the most part end with the buyer and seller going their own separate ways, which, in turn, sometimes leads to an adversarial stance in the negotiations often featuring the use of multiple “walkaway positions” and occasionally some table thumping or other drama. This is often compounded by the fact that a majority of asset deals nowadays tend to be auctions, or at least competitive in some way, which further leads to a singular focus on value maximization. In contrast, I would characterize the negotiations on a well-executed merger to be more akin to a graceful waltz which that the parties must carefully stitch together a mutually beneficial agreement that will then govern their relationship going forward. In fact, I would even venture to say that asset deals and mergers actually benefit from two very different, but not mutually exclusive, negotiator skill sets. On the asset deals, the best negotiators in my opinion are the ones who can play the zero sum game the best. In contrast, the transformational merger of two companies is best handled by a true statesperson skilled at engineering the win-win situation.

How do you typically deal with competitively sensitive information during due diligence?

I think the first and most effective approach is to use independent advisors to review competitively sensitive information. This works particularly well when dealing with accounting records, board minutes, etc., where the advisor can review the information and provide “sterilized” reports to the counterparties. That said, it is often the case that commercially sensitive information must be reviewed by the counterparty’s business people in some way, shape, or form. In these instances, we use “clean rooms” where the commercially sensitive information is reviewed only by people at the counterparty who will not directly engage in that specific business for some stipulated period of time.Finally, we have also found that using aggregated data can also be helpful in some cases to meet diligence requirements without tripping the competition issues.

When it comes to due diligence, what is the most common pitfall you have observed?

It’s critical to have a centralized diligence process run by a deal quarterback who understands what is important and what is not. It is also equally important that the quarterback has adequate clout both within the organization and with the counterparty. This allows them to establish and enforce a materiality standard by pushing back on the unreasonable requests while also having the authority to expedite the reasonable ones.

Perspectives

George Golumbeski

Senior Vice President, Business Development, Celgene Corporation

As a global biopharmaceutical company with a market cap approaching $30 billion, do you have a formal process for approving deals?

Yes, of course; however, they are less formal here than a multinational pharma. I see the CEO, CFO, and COO a few times per week and speak with them about what is going on in the normal course of business. But in any case, we get a leadership group together at least 3–4 times during the course of a deal. First, we have a discussion after due diligence to cover what we think of the opportunity, whether we want to go for it. We also have a review meeting when we reach an agreement on terms and another such meeting when we have finalized a legal contract. Finally, prior to signature, a deal is presented to our Board of Directors. Thus, there is a post-diligence debrief, a term sheet review, a final getting-ready-to-sign review, and a board approval. Those are the consistent checkpoints, and there may be others from deal to deal. But I cannot over emphasize how frequently, just in the casual course of discussion and motivated out of interest, things are discussed on almost a frequent basis with senior leadership.

What are some of your leading practices to focus members of your diligence team whose day job is not M&A?

First, it helps to be in a company that has an agenda to grow the business and that accepts and widely acknowledges that we must be excellent at partnering. We strive to build our pipeline in a disciplined and prudent way, and we like to build our research organization through collaboration. So, one, it helps to have that clear precept in the company. Two, in forming a diligence or deal team, we try to select the right people from the various line functions. Some people have real enjoyment in evaluating opportunities and they are quite good at it, others less so. Third, we allow team members to look at the data and write as lengthy a report as they like, but we’ve developed a list of about five or six questions that go way beyond the minutiae, and each team member has to answer the short list of questions succinctly. It really does focus them on what is the opportunity here and what are the material issues.

How do you avoid getting wedded to the deal so as not to get lost in the trees?

The goals and principles of Business Development really are about providing opportunity for Celgene and driving the organization to make responsible decisions. Pharmaceutical R&D has no guarantees and things may fail, but we have to make responsible, disciplined decisions. It is also about appropriately taking risk. I think that this point is probably the same in all industries, so it is a delicate balance getting a team to focus on the real material issues that are going to make or break a project. On the one hand, we cannot say no to everything because there are always plenty of reasons to say no. On the other hand, we cannot be cavalier and say every deal has risk, so let’s go ahead and do this. This is where experienced Business Development people provide a lot of value in helping the team to strike that balance. Finally, the deal structure should be used to address the risks associated with a given transaction.

Are there additional ways in which you ensure that you are appropriately taking risks and considering it in a measured, balanced way?

This happens day to day on every deal. But in this industry, I think that very experienced business people who have a “big picture” view are very valuable. I will give you an example that came up on one deal early in my career. I think that the toxicologist who reviewed the data said, ‘I am really concerned that there is a huge difference between the way the male and female rats responded to this compound.’ Some members of the deal team who were not toxicologists, seemed to be getting pretty concerned over this. At that point, I was pretty junior in my career but I had seen enough toxicology programs, so I asked, what is the specific worry, do we see compounds of our own that have this specific effect? He said this is actually seen very frequently. I asked if this was a reason to not proceed with the opportunity. His response was ‘No, it is just that I am more intellectually curious about this.’ Thus, deals can die the “death of a thousand cuts” if one does not stick with the real material issues. The flip side danger would be if someone does raise a material issue and the person running the project just steamrolls the issue.

The other thing that helps a company like Celgene is that there is a great culture here of being disciplined but taking appropriate risks. Having a culture and a leadership team that really makes growing the business a priority and sometimes exhorts people to take an appropriate risk is really very helpful. I think good Business Development people are like judges or trial lawyers in a courtroom full of expert witnesses. They are not the experts and there are people in the room who know more about any function than they do, but they have to be able to interrogate and question and probe the various experts such that the truth comes out. And the truth is always going to contain a few risks and those risks have to be laid out extremely clearly, and then an organization can decide whether to take them or not.

Perspectives

Marie D. Quintero-Johnson

Vice President and Director of Mergers and Acquisitions, The Coca-Cola Company

As a company with over $35 billion in revenue selling products in over 200 countries, how does M&A factor in your global growth strategy?

We have a long-term growth model that drives long-term targets for each operating group and a Corporate Development director aligned with the operating group for each of our five geographies. Every strategic planning cycle, each group manager partners with the group management to ensure we understand the market outlook and match our growth trajectory with our business capabilities and see how M&A can accelerate those growth objectives or capabilities. There are a finite number of scaled companies that could make a difference to Coke. Our challenge is to make sure we are prioritizing them with a common set of metrics and then looking beyond the obvious brand companies into capabilities, and that we tie everything into our business planning process.

How do you prioritize transaction opportunities?

Within each group, there is ranking of what is going to drive the fastest growth or create the most value over time. Is it going to accelerate performance? Is it strategic beyond just adding value? In terms of prioritizing across groups, if there are sizeable transactions, and they are all coming up at the same time, then senior management determines which opportunities take precedence over others, based on the global perspective. For that, we use traditional methods: strategic priorities, NPV, accretion dilution, and accelerating growth for the organiztion or region over time.

Can you please describe the range of responsibilities of your Corporate Development team?

Our Corporate Development team has moved beyond just execution. When we were only doing bottling transactions in the 1990s, the strategy was fairly simple and set by the CEO at the time. In the late 1990s, when we increased our focus on brand acquisitions, we had to develop a framework—for use both internally and externally—to better understand the drivers of growth across beverage segments and cross-reference those against the available opportunities. This expanded our role from subject matter experts in transaction management to include strategic advisory support. That is part of our core competency today. As we evolve, the role will become more expansive and our knowledge base will have to be much broader, as will our population of networks. M&A professionals will need to know how to canvas the investment banking universe, as well as universities, science labs, biotech firms, NGOs, and government to look for technologies, ingredients, scientists, or human capital to help us accelerate our capabilities around any specific functional area. I may have fewer accountants or engineers and more consulting, relationship, and marketing type people. However, the common denominator is business and financial acumen. This role is definitely not for introverts—it will be about relationships and influencing.

How are deal opportunities identified and what is the internal approval process?

We have a population of prioritized targets that emanate from the business planning process, but transactions do not have a team allocated to them until something is brought as a live process. Pursuit of each opportunity is endorsed by our senior management to ensure the company is committed to allocating resources to an evaluation. If approved, the team signs NDAs, builds a business case in partnership with the operating groups, anddevelopes a recommendation. The M&A team’s role is that of both consultant and objective advisor. Each business case is reviewed by the CFO and, depending on the size and impact, may also require review by the CEO and Board of Directors.

How does your Corporate Development team stay aligned with the various stakeholders in a deal?

It is quite the art of multi-tasking. I see every transaction and the team is well-versed about the risk parameters of the company. We have the benefit of consistency, with a core team made up of members from M&A, legal, and tax. It works well in ensuring knowledge transfer, for example, if we have a change in the M&A manager, other team members can provide the consistency across a given geography as they know the risk corridors in which we operate. For the most part, the operating management allows us to operate within our subject matter expertise. If there is a business decision that impacts their territory or for which they will have ultimate accountability, they have the opportunity to provide guidance in the process. There is an understanding of what we will ask of them and what they will expect of us. Each operating group assigns a person to the team who is ultimately the owner of the transaction, so everybody’s interest is covered.

The partnership with the operating groups is the most important facet of the role—earning the trust to allow for constructive discussions in developing reasonable valuations that support each business case. Ultimately, the M&A team and operating groups must arrive at a common point of view on value and risk. That influencing to the appropriate risk corridor is part of our job. It is not defined by a concrete set of rules, but there is enough consistency on each deal team to learn what that corridor is. From an accountability perspective, the operating groups ultimately sign off and commit to the valuation put forth for approval.

How do you evaluate performance on any particular deal?

We have two mechanisms. On an annual basis, we review the value of most of our acquisitions through our FAS 142 process. In addition, on an annual basis, we review the performance of the transactions completed in the last five years and do a comparison of actuals versus projections. We are looking to become more disciplined around measuring transaction success a few years out and are developing a scorecard to help us get there. This will be particularly important as we implement economic profit.

How do you assess the performance of your Corporate Development team?

Everyone has objectives at the beginning of the year, which we review a couple of times a year. It is based on individual development. If someone is new, I expect that they learn the process, learn the basics. An analyst needs to perfect valuations and due diligence. Someone who is at the manager level needs to run deals with minimal supervision and drive strategic thinking. So it really is individually based. Ultimately, the effectiveness of the team is based on the value that we add to the corporation and to the operating groups—and this is best captured by the trust that management and the operating teams put in individuals and in the output of the group. The other metric of success is the placement of individuals in leadership positions in the company. Over the years, we have had a great track record of developing talent for the corporation. This, for me, is a sign that we are developing the right skills to add value, not only as M&A members, but also as business professionals.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.