Identifying ‘unknown unknowns’: a perspective on non-traditional competition

15 minute read

01 April 2020

The changing nature of competition poses increasing challenges to business models beyond those posed by traditional competitors. Companies need to undertake periodic exercises to gain a sense of the direction from where such threats can arise.

The nature of competition in the modern world is changing, a reflection of how the business of business is dramatically transforming. Whereas technological disruptions – from the steam engine to electricity to the internal combustion engine to the computer chip – used to come once a generation, today they come fast and furiously, with dozens of innovations seeming to emerge annually.

Learn more

Explore the strategy collection

Learn about Deloitte's services

Go straight to smart. Get the Deloitte Insights app

One of the most powerful to have appeared is the internet. It may be only 30 years old, but the internet has inspired a fundamental technological shift away from business approaches of the past. Today, seven of the ten most valuable companies globally are based on digital platforms, websites and apps that compete for our valuable screen attention.1 Alibaba, Alphabet, Amazon, Facebook and others have all grown exponentially, while helping shift economic behaviour away from bricks and mortar businesses to a digital world powered by algorithms.

Such services are now the expected, indeed, preferred domains for many human activities, such as banking, dating and entertainment. As digital technologies further develop, they are making inroads into industries such as automotive, energy, transportation and health care. As this process continues, new competitors emerge and cause disruption by muscling into markets once considered stable and distinct.

Established firms can struggle to address the strategic challenges of such non-traditional competition. A recent example is Thomas Cook, a global tour operator that closed in September 2019. There were many factors involved in the collapse of the 178-year-old British company, including ballooning debts, an ill-fated merger with MyTravel in 2007 and uncertainty surrounding Brexit.

However, a significant factor was a change in the way people travelled. The rise of the internet enabled travellers to ‘create their own adventure’ and book directly online with service companies such as Airbnb, easyJet and Ryanair, bypassing expensive high street travel chains.

In the end, Thomas Cook collapsed not because the British stopped taking holidays: 60 per cent of the population took a holiday abroad in 2018. It is how people holidayed that changed. Just one in seven travellers now goes to a high street travel agency to buy a holiday. Those who do tend to be over 65, and in lower socio-economic groups that have less money to spend. Thomas Cook, with its 560 high street outlets, was caught out by this shift of travellers’ spending to non-traditional competitors.2

Business school textbooks are filled with similar cases. Video rentals, mobile devices and camera-related companies are a few of the many companies whose fates are seen to have been sealed by non-traditional competition that appeared because of combinations of innovative technologies, evolving regulations and fast-changing consumer demand. Such conclusions are based on the wisdom of hindsight. The more relevant question for companies facing non-traditional competition today is, how can they identify ‘unknown unknowns’ that may render their business model obsolete and cause them to become the next Thomas Cook?

A path to identifying ‘unknown unknowns’

It may seem quixotic to seek to identify something that is by definition unidentifiable. Yet, the changing nature of competition means that organisations will face increasing challenges to their business models beyond those posed by traditional competitors. Such non-traditional competition could imperil the existence of incumbent companies. Organisations need to discipline themselves to undertake periodic exercises to gain a sense of the direction from where such threats can arise.

We believe there is a simple three-step process that enables organisations to frame the unknowable. These are:

- Don’t be shackled to the value chain

- Adopt a ‘Why not?’ mindset in order to turn weak spots into opportunities

- Use the analysis of weak spots for strategic planning

Don’t be shackled to the value chain

When thinking about competition, organisations can fall into the trap of focusing only on rivals with similar assets, clients, intellectual property and/or products and services. In terms of the existing market, it is critical to be aware of the business model of rival firms. While they may have comparable products and services, they could also have very different value chains that produce those products and services that could prove more innovative than the current approach of an organisation.

As an example, interest in electric vehicles (EVs) was aroused in the late 1990s when mid-sized hybrid vehicles were launched on the market. Those vehicles proved so popular that by 2002, The Washington Post described them as “Hollywood’s latest politically correct status symbol.”3 Part of its attraction for the media world was the price tag, which meant the car entered into the market segment of German premium cars, paving the way for such start-ups as Tesla. In turn, Tesla has inspired such outsiders as the Chinese Nio to turn their attention on the segment.

Michael Porter, who first popularised the idea of value chains, would see Tesla having a source of competitive advantage over traditional car manufacturers in terms of battery technology evolution, consumer expectations (e.g., full self-driving capabilities) and from increasing environmental pressure.4 However, the more pertinent question in terms of competition is, did anyone within the industry see Tesla coming?

While the approach of value chain analytics provides an understanding of competitive dynamics within a market, it can, however, fail to identify threats from new and different competitors that may be emerging externally to the industry. A competitive analysis should extend beyond the immediate market and rival firms. Richard Norman and Rafael Ramirez, for example, argued in 1993 that the concept of the value chain was outdated, suited to a slower changing and linear world of comparatively fixed markets.5

For this reason, we encourage organisations to look beyond value chains and embrace entire ecosystems in their search for potential threats. Ecosystem refers to the network of organisations – including suppliers, distributors, customers, competitors, government agencies and so on – involved in the delivery of a specific product or service through both competition and cooperation.6 We recommend a three-stage approach to this examination.

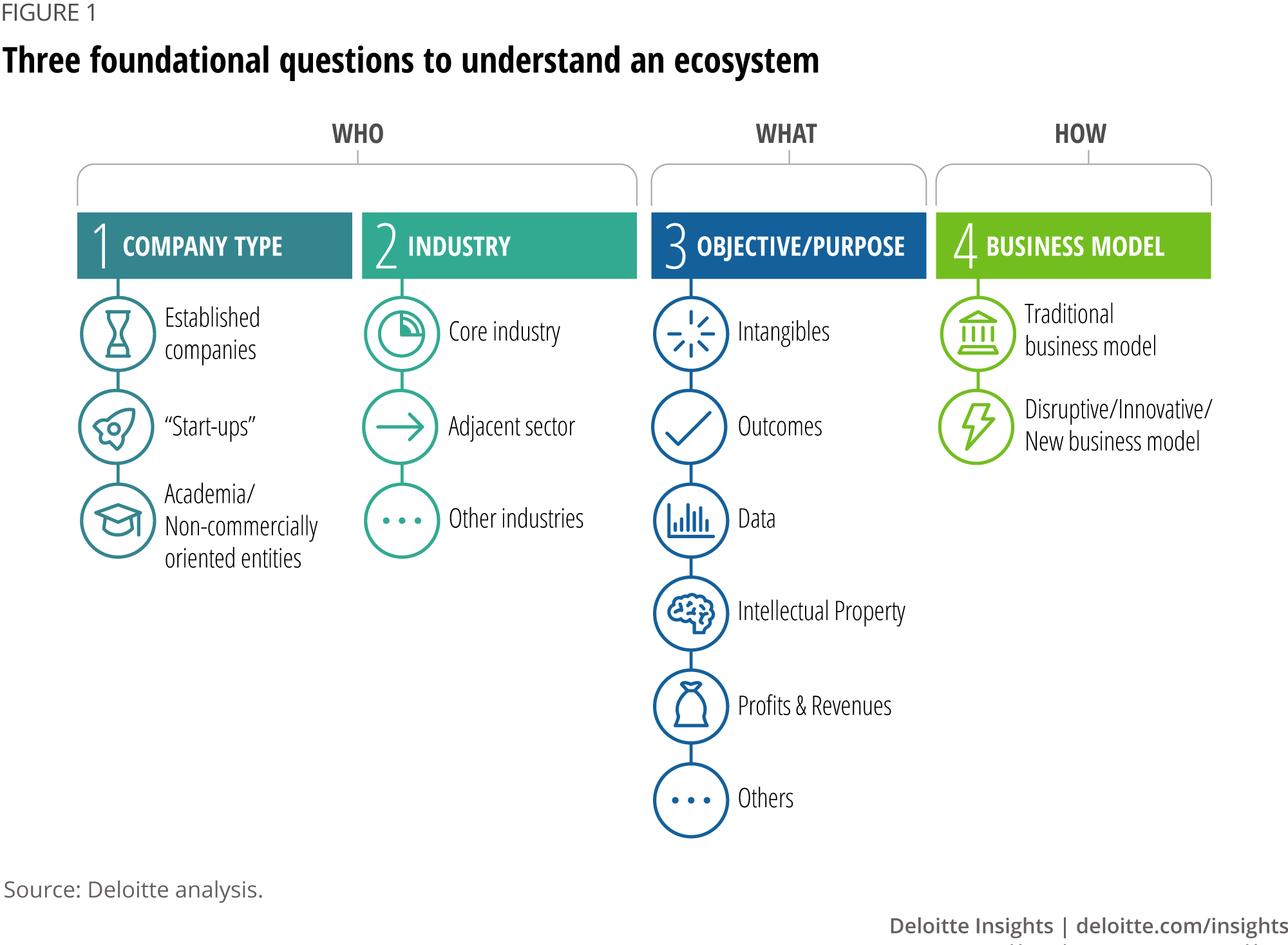

a) Analyse ecosystem stakeholders by type, purpose and business model

To gain a better understanding of stakeholders involved in an ecosystem and to identify competitive dynamics, organisations should seek to answer three fundamental questions in their analysis:

- Who are the stakeholders in the ecosystem?

In particular,- Type: Are they an established organisation, an emerging start-up or a non-profit such as an association, government body or a public university?

- Industry: Are they traditional players, come from an adjacent business sector or do they come from a completely different background?

- What are the objectives of these stakeholders?

Their objectives can be extremely different and may relate to, for example, data collection, trust, outcomes (best product/service), or intellectual property. - How do they operate in their environment? What is their business model? Is it traditional or disruptive/innovative?

Focusing on the broader ecosystem can help organisations identify ways to create value through ‘positive-sum competition’; that is, through looking at the whole picture and avoiding the typical downward spiral of cost-focused differentiation.

b) Identify ecosystem weak spots and build hypothetical sources of non-traditional competition

Analysis of the purpose and business model of each type of stakeholder helps to identify ‘weak spots’ upon which hypotheses can be built. Weak spots are elements in the ecosystem where disruption from non-traditional competition can arise. The following are examples:

- Significant customer agitation. An example is how video-on-demand platforms disrupted the movie rental business by providing better service than DVD rental stores at a competitive price with flat-fee unlimited rentals. In the music industry, services such as audio streaming platforms tapped into customer demand for single songs rather than full albums.

- Ability to reduce CAPEX/OPEX substantially. Online marketplaces increasingly rely on robotics and automation to reduce costs and increase efficiency in their distribution facilities.

- Risk of competitor entry with fundamentally different operating constraints. For example, nickel mining companies from several emerging markets have limited environmental/regulatory constraints on their operations, have access to subsidised or free energy and do not have to meet specific ROI/profitability targets because of their ownership structure. This allows them to sell nickel at lower prices, threatening companies from countries with more restrictive regulations.

- Potential to bypass existing regulations. Ride-hailing companies’ rapid emergence is the textbook example. There have been companies entering the highly regulated taxi industry by arguing that the relevant legislation is not applicable to its services.

- Poor intellectual property protection/enforcement. CAR-T therapies in cancer are now being explored by hospitals through clinical trials with no support from the pharmaceutical industry (see the case described in this report).

- Different value creation objectives. The tech start-up world over the past few years shows a disproportionate focus on growth with limited to no pressure from investors on companies to be profitable. This creates a vastly different sets of dynamics for such companies in comparison to industry incumbents.

c) Confirm hypotheses through quantified analysis

The level of activity within the ecosystem around suspected weak spots could be an indicator of the risk of disruption/entry of non-traditional competitors. In this context, ‘activity’ can refer to fund inflows, government attention, specialised press literature, start-up activity or public opinion/sentiment. For example, a large number of well-funded start-ups seeking to enter a specific stage of the ecosystem’s value chain likely indicates a weak spot.

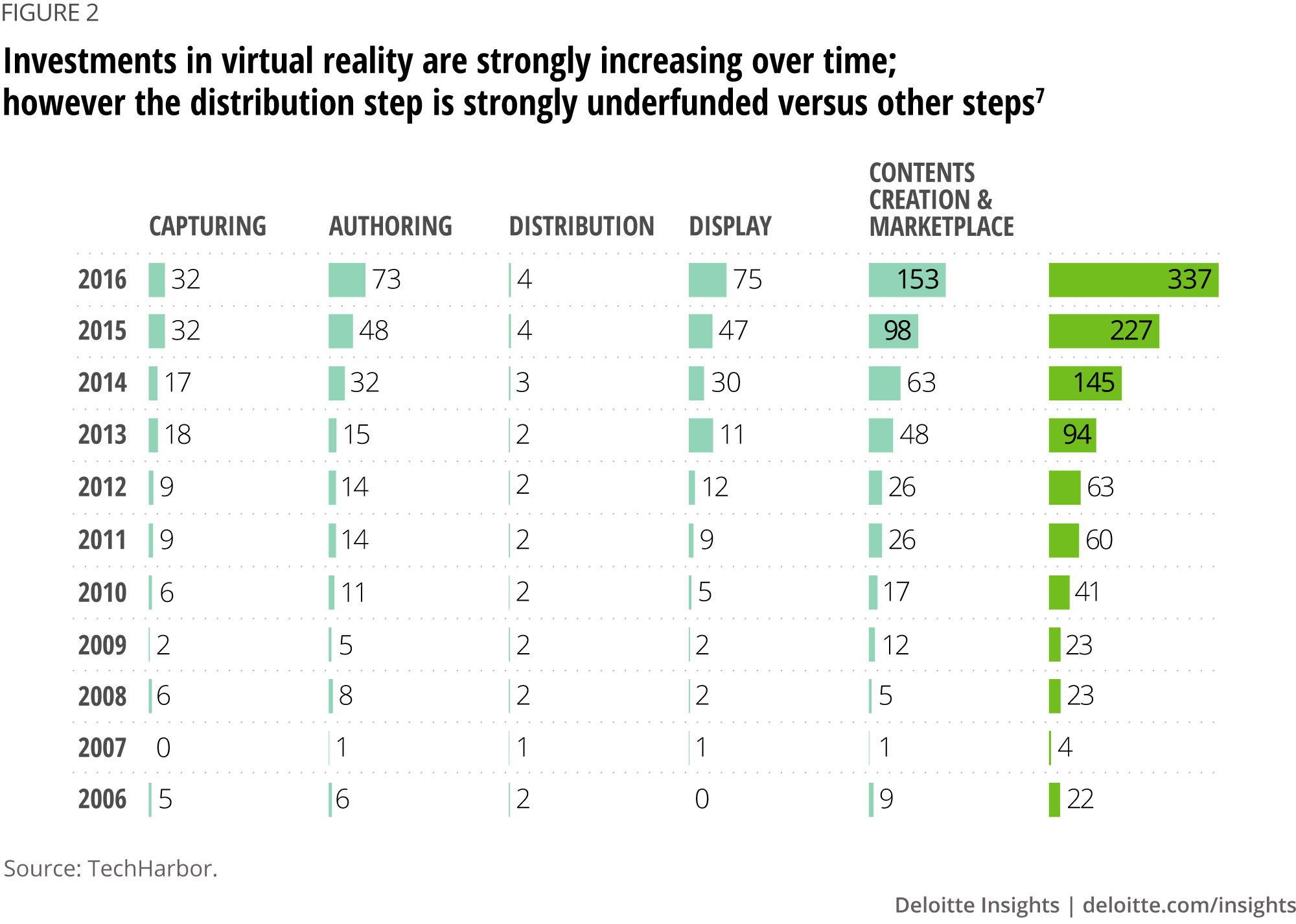

There is a range of tools available to help organisations measure the level of activity at specific stages in its value chain. For example, TechHarbor, a proprietary tool developed by Deloitte, aggregates data on over a million start-ups and provides insights on their activity and funding flows. With TechHarbor it is possible to quickly identify new start-ups to ensure organisations are aware of emerging players in disruptive technology in specific markets.

For example, we have used data from TechHarbor to analyse the level of activity across the value chain of the virtual reality industry and to examine how it changed over time. Based on global start-up data sources, the web-based visualization interface provides valuable insights to customers more accurately and efficiently when combined with experts’ insights.

The chart below shows there was robust growth in each stage of the value chain over recent years, with the number of virtual reality start-ups increasing 40 per cent every year. This is an indication that the virtual reality field is booming and not yet mature. Interestingly, however, the distribution stage in the value chain has experienced a much lower level of start-up creation. A reason for this ‘underfunding’ might be the high level of investment required and the prospect of a ‘winner-takes-all’ outcome that might discourage start-ups from investing in this area.

How Tesco revolutionised retail

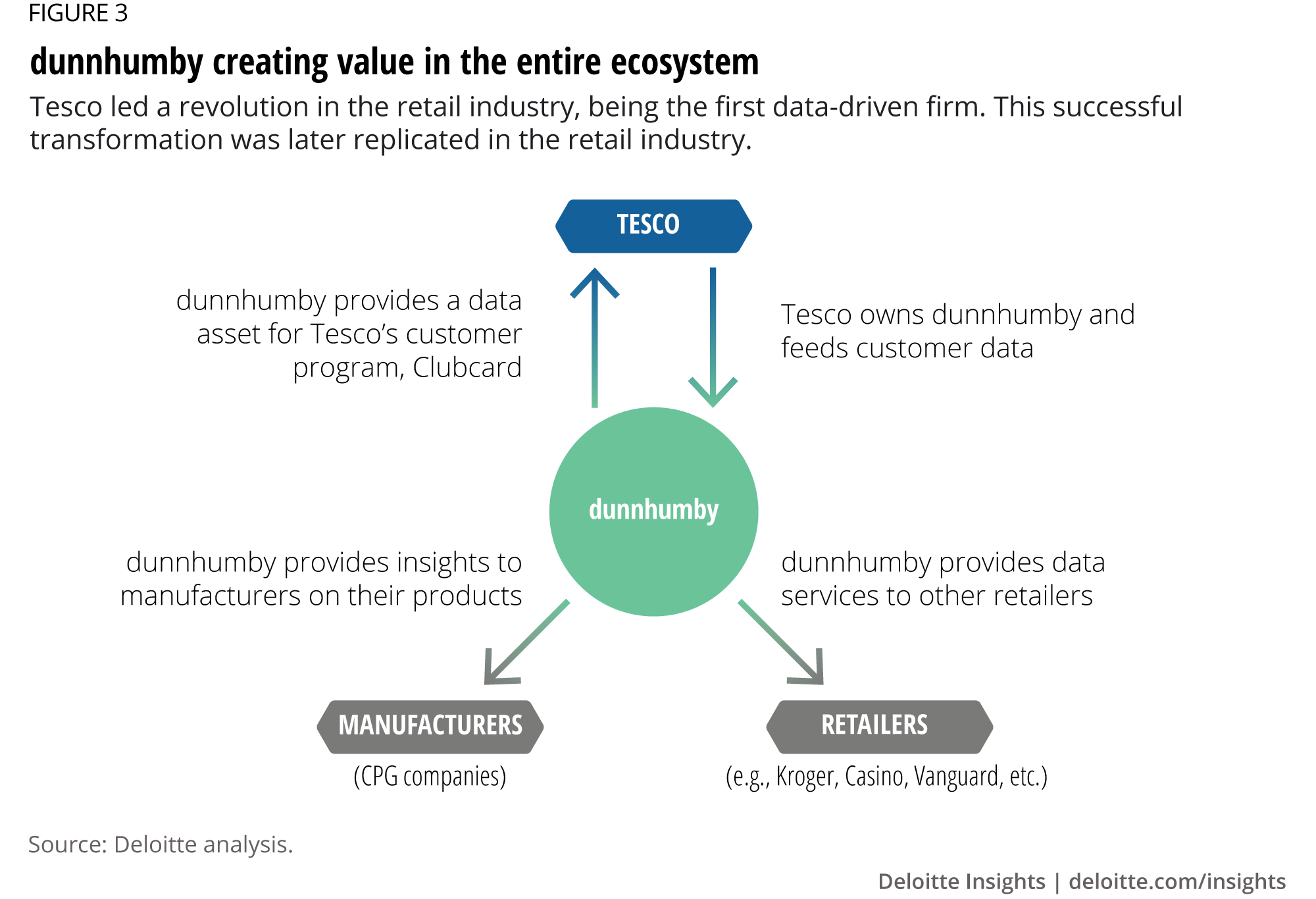

At the end of the 1990s, Tesco, a UK major grocery retailer, trailed Sainsbury’s in the domestic market but could rely on an under-exploited asset: their Clubcard loyalty program. Although quite standard in its mechanics, the program was collecting large and comprehensive amounts of customer data. Convinced that customer data could be turned into a key asset for the company, Grant Harrison, who was charged with researching the project, stepped outside the confines of the retail industry to speak to Clive Humby from dunnhumby, a global customer data science company that was then working with clients that included Cable & Wireless and BMW.

After successful trials on limited data sets with dunnhumby, the revamped Tesco Clubcard program was scaled, enabling the retailer to adapt its overall strategy (store formats, assortment, private labels positioning, promotional activity…) based on customer behavioural analytics.8 Tesco was then the first retailer to use data-driven marketing and segmentation at a corporate strategy level, and the partnership with dunnhumby proved so successful that it enabled Tesco to dominate for several years and reach the number-two position in global retailer ranking, inspiring the first data-driven strategy in the retail industry.

From a partnership in the 1990s, Tesco bought a stake in dunnhumby in the early 2000s until fully owning the firm. The model rapidly expanded to bring insights to consumer packaged goods (CPG) companies then to retailers in countries where Tesco is not present. This move progressively increased the amount of data accessible for dunnhumby, and dunnhumby also benefited from diverse sources of data such as online sales, digital marketing responses, etc. From a core model evolution, Tesco converted dunnhumby into a source of additional revenues when providing insights to its ecosystem.

Tesco led a revolution in the retail industry, being the first data-driven firm. This successful transformation was later replicated in the retail industry.

2. Adopt a ‘Why not?’ mindset in order to turn weak spots into opportunities

Ask ‘Why not?’ more often

To gain a deeper understanding of the dynamics of an ecosystem, an organisation must be prepared to challenge orthodoxies to identify weak spots. In practice, this means going beyond strongly held beliefs about ‘how things are done around here.’ Such orthodoxies can be linked to the culture of a specific organisation or to an entire industry.

Take the airline industry. One of the many orthodoxies prevalent in the American industry was to charge business travellers the highest fares. When Southwest Airlines appeared on the scene in June 1971, it immediately set about flipping orthodoxies. Incumbent airlines then all ran similar kinds of businesses. They flew passengers in multiple types of planes via major hubs and then on to their desired airport.

Southwest used only one type of plane to cut down on maintenance problems and make sure replacement parts were always available. In addition, all planes flew directly ‘point to point’. Importantly, the emphasis was placed on the customer experience with business travellers in particular being the beneficiaries of an aggressive pricing policy.9 Today, Southwest is the world’s largest low-cost carrier and in 2020 reported its 47th consecutive year of profitability. Its no-frills approach has been copied successfully by other budget airlines in Europe.

It is essential to be ruthless in searching for ways to challenge orthodoxies and to be open-minded when it comes to confronting uncomfortable truths. One reason why outsiders are still able to enter and upend markets two decades after Harvard Professor Clayton Christensen’s identified and analysed theories of disruptive innovation10 is that industries and markets can be just as beholden to the ‘way things are done’ as companies are.

One powerful method to break this constraint is to start asking ‘Why not?’ on a more regular basis. These two simple words can challenge preconceived notions and ensure organisations are not falling into bad habits or missing opportunities. While the answers to the question may show the solution to be infeasible, the exercise will allow leaders to think differently about received wisdom. And it may, just may, result in an entirely new business strategy. Asking ‘Why not?’ led Piaggio to create a motorcycle with two front wheels, bringing more security to users and making more powerful motorbikes available without any specific driving licenses.

Turn weak spots into opportunities

The identification of weak spots, particularly concerning non-traditional competition, enables a systematic view of potential strategic opportunities. While every situation is unique, this approach can turn questions about weak spots into opportunities:

- How can the value proposition (that is, the sum total of offering and experiences delivered to customers during their interactions with an organisation, product or brand) evolve/transform to differentiate an organisation and best meet/shape customer demand?

In mobility, interactions with customers are moving to a Mobility-as-a-Service (MaaS) concept. To go beyond the car, Daimler bought Chauffeur Privé, a French ride-sharing company, to expand their value chain. Chauffeur Privé was later renamed Kapten to expand the service to a broader geographical area.

- Is it better to build your own ecosystem or take part in a ‘disruptive’ ecosystem? If an ecosystem is built, should it be closed and controlled or open to others?

Nestlé created its own ecosystem when launching the Nespresso single-use espresso capsule by cultivating a network of coffee machine manufacturers that would be compatible with the new patented capsule.

- Should an organisation push for a change in regulation to optimise an ecosystem?

For example, pushing for adaptive regulation may be beneficial. In Finland, the government recognised the need to reform transport regulations to support a vision of MaaS, which considers transportation as an integrated system of different services. Instead of having separate codes and laws for taxis, roads and public transport, Finland now has a fully integrated transportation code.11

- Should an organisation partner with non-traditional competitors or consider competition to make the most of complementary capability/offerings? Should these partnerships be exclusive?

Competition can also be a way of stimulating innovation. An example is competition among biotechnology firms to increase technology diversity and develop new products. Johnson & Johnson Innovation Centres provide external scientists and entrepreneurs with direct access to data in order to leverage cross-fertilization with its ecosystem.12 Thus, the pharmaceutical industry leapt from fully integrated to highly networked and partnered R&D.

To support the growth of its coffee division and retain market share, Nestlé agreed to a deal with Starbucks to support their coffee distribution in selected geographies, highlighting the collaboration between competitors in sharing channels to market.

- Should an organisation acquire non-traditional competitors?

The rationale for acquiring a non-traditional competitor may be to increase revenue or achieve cost savings through synergies through complementary offerings, or to maintain market position.

- How and when should an organisation take the risk to transform itself? And if the organisation is not ready to transform, should it seek to become a non-traditional competitor in other parts of the business and explore weak spots of other (adjacent or completely new) ecosystems to find new sources of innovation, competitive differentiation and growth?

IBM is a classic, albeit very compelling example of a company that found new sources of differentiation and innovation. Considered a true success story in the 1960s and 1970s, the company achieved market dominance in the mainframe computing segment. However, a subsequent move into personal computers (PC) turned out to be more problematic, with new competitors arriving with much cheaper, so-called cloner PCs. The company was forced to re-think their business model, moving away from a pure focus on hardware, to a business services model, leveraging the company’s expertise and knowledge as a global IT player.

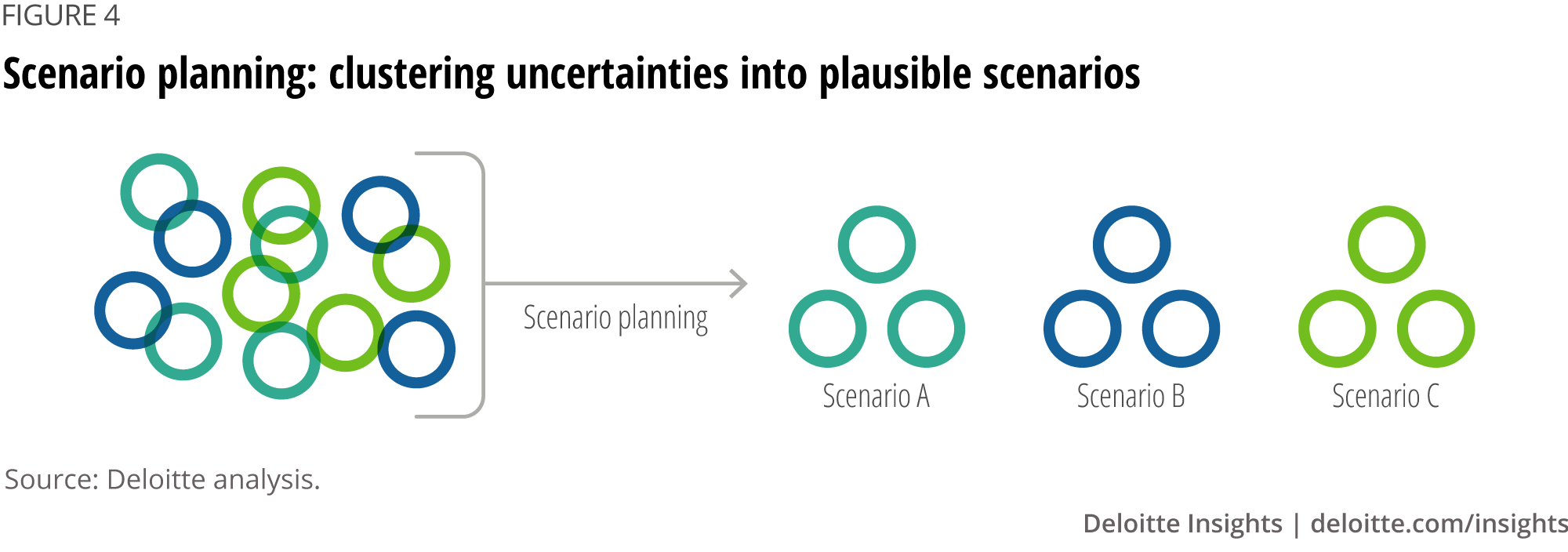

3. Use the analysis of weak spots for strategic planning

Weak spots identify the most probable and/or impactful uncertainties in your ecosystem. Once you have identified weak spots in the ecosystem and built and confirmed hypotheses, we believe that scenario planning is the best way to inform strategic choices. Scenario planning based on weak spots is about envisioning different plausible futures.

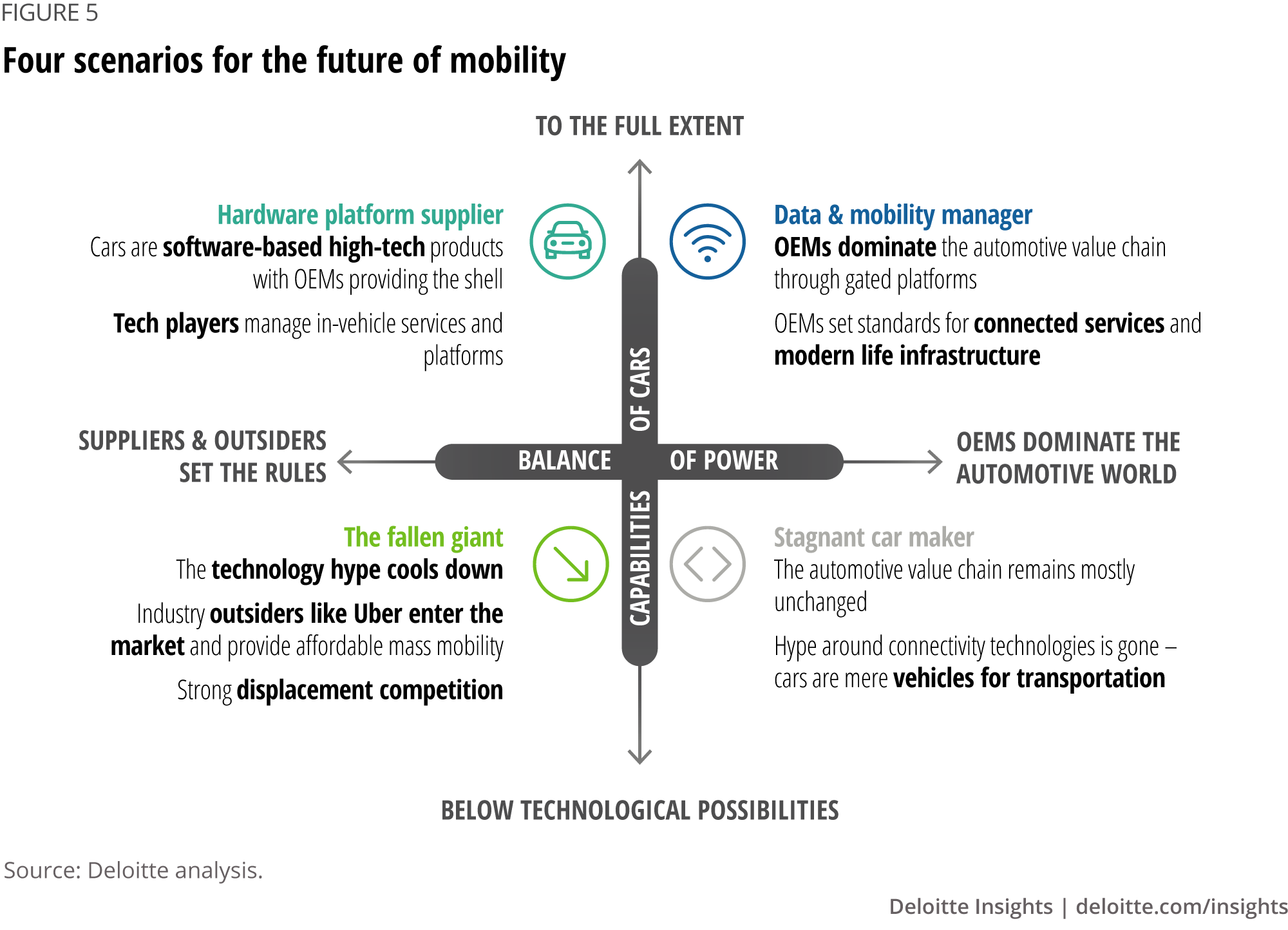

Take the mobility ecosystem as an example.13 Four scenarios characterizing potential weak spots emerge from two major uncertainties about the future, relating to:

- The balance of power between OEMs (original equipment manufacturers; that is, car brands) and automotive component suppliers: Will digital platforms manage to commoditise car manufacturers, or will car manufacturers continue to dominate the automotive ecosystem?

- Capabilities of cars: Will technological innovation continue at the current pace, or will it slow down?

Example of a weak spot and opportunities

Non-traditional competition in the field of CAR-T therapies in cancer

CAR-T cell therapy is a major scientific breakthrough in oncology. Unlike most cancer treatments, CAR-T therapies do not involve taking a pill or injecting a fluid, but rather a process that consists of extracting the patient’s own T-lymphocytes, re-engineering them and then reintroducing them to the patient where they act as a ‘living drug’, identifying and killing cancer cells. The field for CAR-T is currently booming, with over 800 clinical trials running. However, a potential weak spot for pharmaceutical companies may be emerging due to significant challenges, including:

- A completely different unit of sale (i.e., a process, not a drug), which represents a notable change in how stakeholders traditionally discuss value

- A high price, driven by significant value brought to patients, substantial investments in research, low patient volumes (the process is personalised, challenging scaled production), and higher COGS than usual (the process is complex, with strict supply chain requirements)

- Health care systems (public or private) facing increasing economic challenges to fund innovative treatments and in need of reducing costs

Hospitals participate in CAR-T therapy in several ways. First, they can be involved in clinical trials sponsored by pharma companies. This is the traditional setup with CAR-T produced by the pharma company and administered on-site at hospital. Hospitals can also be involved in CAR-T therapy in non-traditional manners, including by running ‘in-house’ clinical trials on potential new CAR-T treatments on its own. Hospitals can also be involved in multi-centre coordinated research initiatives.

CAR-T therapies produced by hospitals could challenge pharma companies in several ways:

- Capital expenditure required to produce CAR-T therapies is not high. As treatment is personalised to each patient, small facilities can compete with larger ones.

- Regulatory barriers prevent non-pharma players from engaging in production. However, under the EU ‘hospital exemption’, hospitals and universities can produce limited volumes in a clinical trial setting.

- Intellectual property frameworks are different from traditional pharma products, and unlike traditional molecules that can be patented, CAR-T treatments are about patenting a specific process.

- The question is:

Could hospitals enter CAR-T production for ‘commercial’ use, motivated by the opportunity to lead scientific advances and strengthen their reputation, and incentivised by health care systems looking to save costs?

When we analysed the activity of hospitals in the EU based on publicly available data, 58 per cent were found to be involved in developing their own CAR-T, either alone or as part of a coordinated initiative.14

The future of CAR-T production is uncertain due to the novelty of the treatment, which is redefining the traditional boundaries between R&D and commercialisation. But the financial amounts at stake, health care system deficits, the clinical prospects for the treatments, and the technical feasibility all create a fertile ground for non-traditional competition that could disrupt the viability of the current model of oncology treatment for pharmaceutical companies.

Implications: What businesses need to do next

The classic model of competition holds that companies compete in well-defined industries selling similar sets of products and services. A company developed its competitive advantages within its field by pursuing economies of scale or focusing on attributes such as efficiency and quality.

If this definition ever held true, then it is well and truly obsolete by now. As outlined in this paper, the lines between markets are blurring and competition is becoming more complex, dynamic and multi-faceted as disruptive market entrants transform entire industries. This paper is full of many examples of organisations that have been caught off guard.

Formulating business strategies in this world of unprecedented change and pace is difficult. This is made even more challenging by the fact that identifying competitors is a far more elusive task than it has ever been. Organisations not only face traditional competitors, but they also must scan the horizon constantly for actors that represent non-traditional forms of competition.

Within this paper, we have presented a simple three-step process that enables organisations to frame the unknowable and remain alert for such intruders. These are:

- Don’t be shackled to the value chain

- Adopt a ‘Why not?’ mindset in order to turn weak spots into opportunities

- Use the analysis of weak spots for strategic planning

This process will enable organisations to forewarn themselves so as to be forearmed against non-traditional competitors. Once having initiated this process, companies need to institutionalise this approach and embed it as a core capability within the organisation. Today’s business environment is evolving so rapidly that a one-off analysis can pass its use-by date within only a few short months.

A clever organisation will seek to use all the potential tools and resources within its network to identify the emergence of such non-traditional competition. In this way, it will be prepared to develop a strategy to counter serious threats emerging out of the unknown.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.

Explore the Future of Mobility

-

Strategy Collection

-

Industry 4.0: At the intersection of readiness and responsibility Article5 years ago

-

Building business resilience to the next economic slowdown Article5 years ago

-

The duct tape guide to digital strategy Article5 years ago

-

The duct tape guide to digital strategy Podcast6 years ago

-

Reimagine risk: Thrive in your evolving ecosystem Article6 years ago