Feeling the heat? Companies are under pressure on climate change and need to do more

10 minute read

12 December 2019

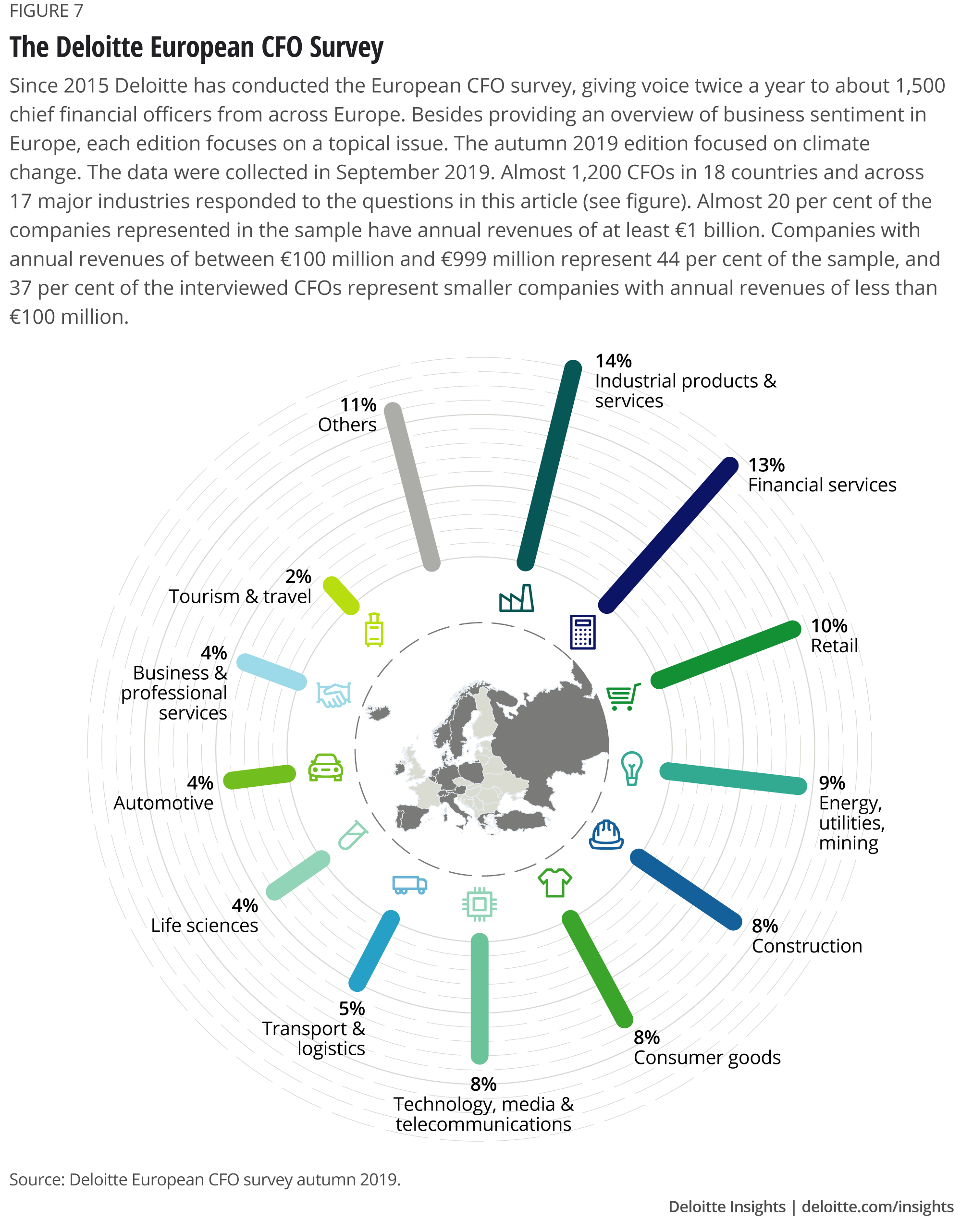

In the latest edition of the European CFO Survey, close to 1,200 CFOs were asked about their company’s measures against climate change. The results reveal a mixed picture with measures focusing on short-term cost-savings.

In the latest edition of the European CFO Survey, close to 1,200 CFOs were asked about their company’s measures against climate change. The results reveal a mixed picture with measures mainly focusing on short-term cost-savings.

Learn More

Explore the EMEA economics collection

Explore the Strategy collection

Download the Deloitte Insights and Dow Jones app

Subscribe to receive related content

2019 may be remembered as the year when climate change activism went mainstream. At the end of September, in a series of rallies timed to coincide with the United Nations climate summit, an estimated six million people in more than 180 countries took to the streets to demand far more action to cut greenhouse emissions. This was probably the biggest climate protest in history.1 Protests in the form of school walkouts had taken place throughout the world for a whole year. The ‘Extinction Rebellion’ initiative has added a further edge by seeking to demonstrate the potentially catastrophic consequences of inaction.

The build-up to this high level of awareness and activism has been slow. Government action began more than 30 years ago when the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) was established, in 1988. The first global climate treaty was reached at the Rio Earth Summit in 1992. The Kyoto Protocol was adopted in 1997. The 2015 Paris Agreement to limit temperature increase and thereby substantially reduce the risks and impacts of climate change is a more recent effort to curb carbon emissions and has been ratified by 187 countries to date.2 Over the last two years, mounting public awareness, fanned by widespread perception that extreme weather events are becoming more frequent, and by the growing weight of scientific evidence on changing weather patterns,3 has added further urgency to the debate. The result is that a wide range of actors are now evaluating the implications of climate change.

Central banks and other supervisory authorities are now considering climate change as a risk to financial stability. This has led to the establishment of the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) in 2015, and the Network for Greening the Financial System (NGFS) in 2017. Both are concerned with enhancing the quality of climate-related awareness, risk management and transparency.

Deloitte asked 1,168 CFOs what their companies are doing on climate change. Their responses reveal:

- there is an increasing pressure to act from a broad range of stakeholders

- companies’ climate responses focus primarily on measures that have a short-term cost-saving effect

- a thorough understanding of climate risks is rare

- few companies have a governance and steering mechanism in place to develop and implement comprehensive climate strategies

- targets for carbon emission reductions are usually not aligned with the Paris Agreement.

Investors, too, are making the climate more central to their activities. As of 2018, more than US$30 trillion in funds were held in sustainable or green investments in the five major markets tracked by the Global Sustainable Investment Alliance, a rise of 34 per cent in just two years.4 Almost 400 investors representing more than US$35 trillion in assets under management (AUM) have signed the Climate Action 100+ initiative, which is committed to pressurising the largest corporate greenhouse gas emitters to “curb emissions, improve governance and strengthen climate-related financial disclosures.”5 At the recent UN climate summit, a group of the world’s largest investors, with more than US$2 trillion in AUM, initiated the Net-Zero Asset Owner Alliance, committing themselves to reaching carbon-neutral portfolios by 2050.6

Heads of states and cities are also increasing their focus on climate change. To support the achievement of the Paris Agreement, the EU in 2017 launched its Action Plan for Financing Sustainable Growth, aimed at – among other things - channelling more money towards climate-friendly business activities. More than 60 countries and 100 cities around the world have adopted net-zero carbon emission targets – with the UK and France recently joining Sweden and Norway among the group of countries that have enshrined the targets into national law.7

1. What is the impact of climate change on business?

There are multiple impacts of climate change on companies. On the one hand, it creates a series of new business risks. Besides the most obvious physical risks (for example, the operational impacts of extreme weather events, or supply shortages caused by water scarcity), companies are exposed to transition risks which arise from society’s response to climate change, such as changes in technologies, markets and regulation that can increase business costs, undermine the viability of existing products or services, or affect asset values.8 Another climate-related risk for companies is the potential liability for emitting greenhouse gases (GHG). An increasing number of legal cases have been brought directly against fossil fuel companies and utilities in recent years, holding them accountable for the damaging effects of climate change.9

But climate change also offers business opportunities. Firstly, companies can aim to improve their resource productivity (for example by increasing energy efficiency), thereby reducing their costs. Secondly, climate change can spur innovation, inspiring new products and services which are less carbon intensive or which enable carbon reduction by others. Thirdly, companies can enhance the resilience of their supply chains, for example by reducing reliance on price-volatile fossil fuels by shifting towards renewable energy. Together, these actions can foster competitiveness and unlock new market opportunities.

2. Do companies feel the pressure to act on climate change?

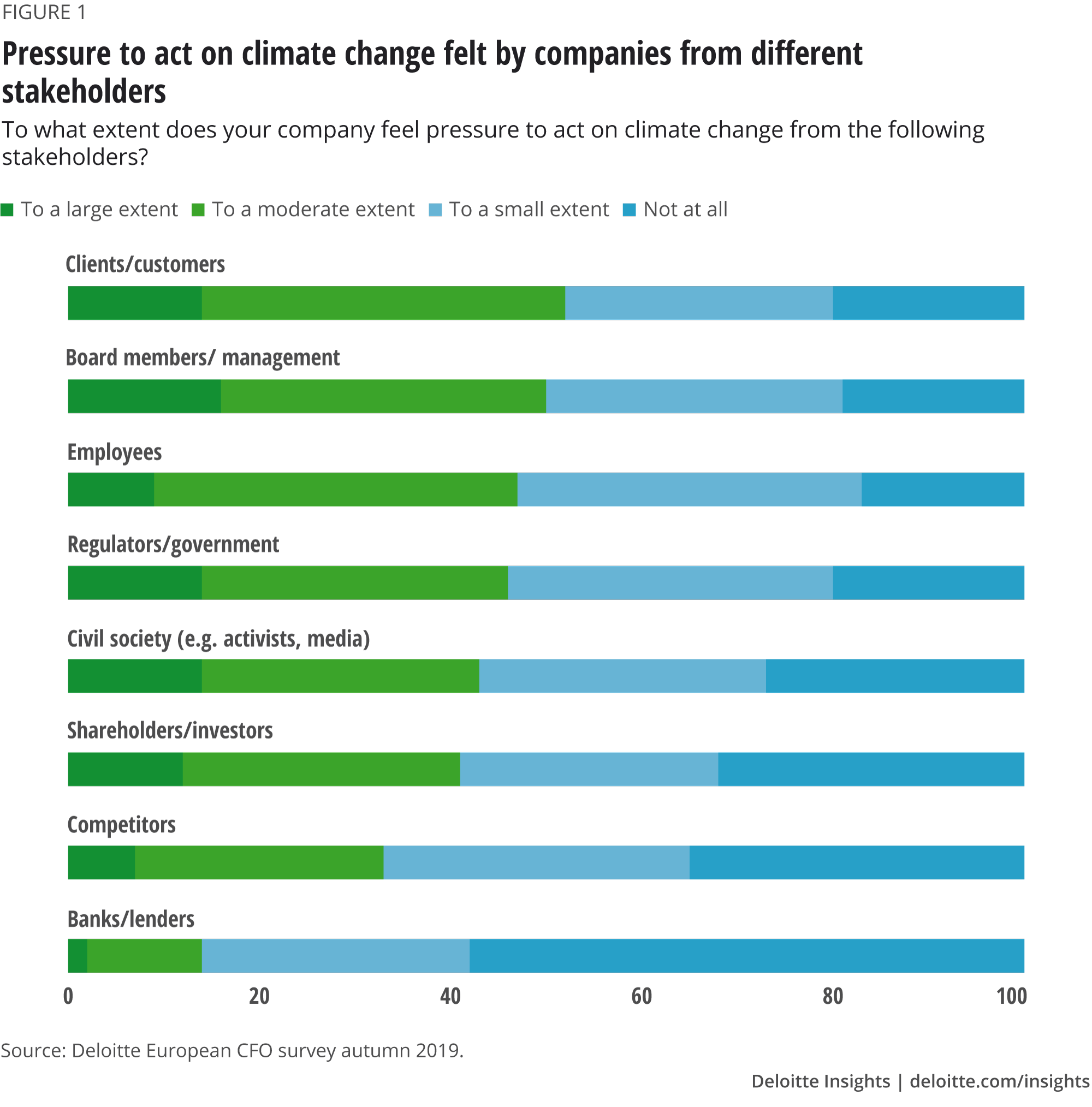

To gain a better understanding of how companies perceive the issue of climate change, the latest edition of the European CFO survey asked close to 1,200 financial executives across Europe to what extent their companies are feeling the pressure to act and what precisely they are doing.10 The survey shows that most companies are feeling the pressure from various stakeholders. Clients and customers are most often named as sources of significant pressure, but employees, regulators, civil society and investors are not far behind (figure 1).

The degree to which companies are feeling external pressure varies greatly. About 30 per cent do not perceive significant pressure from anyone, while for 19 per cent the pressure comes from only one or two stakeholders – usually from regulators and civil society. Larger companies (defined as those with annual revenues of €1 billion or more) are more likely to feel the pressure from several sides, with almost two-thirds (61 per cent) of CFOs reporting that they feel the pressure to act from three or more stakeholders and almost 70 per cent feeling under pressure from clients. By contrast, the regulator is the main source of pressure on smaller companies (that is, with annual revenues of up to €100 million).

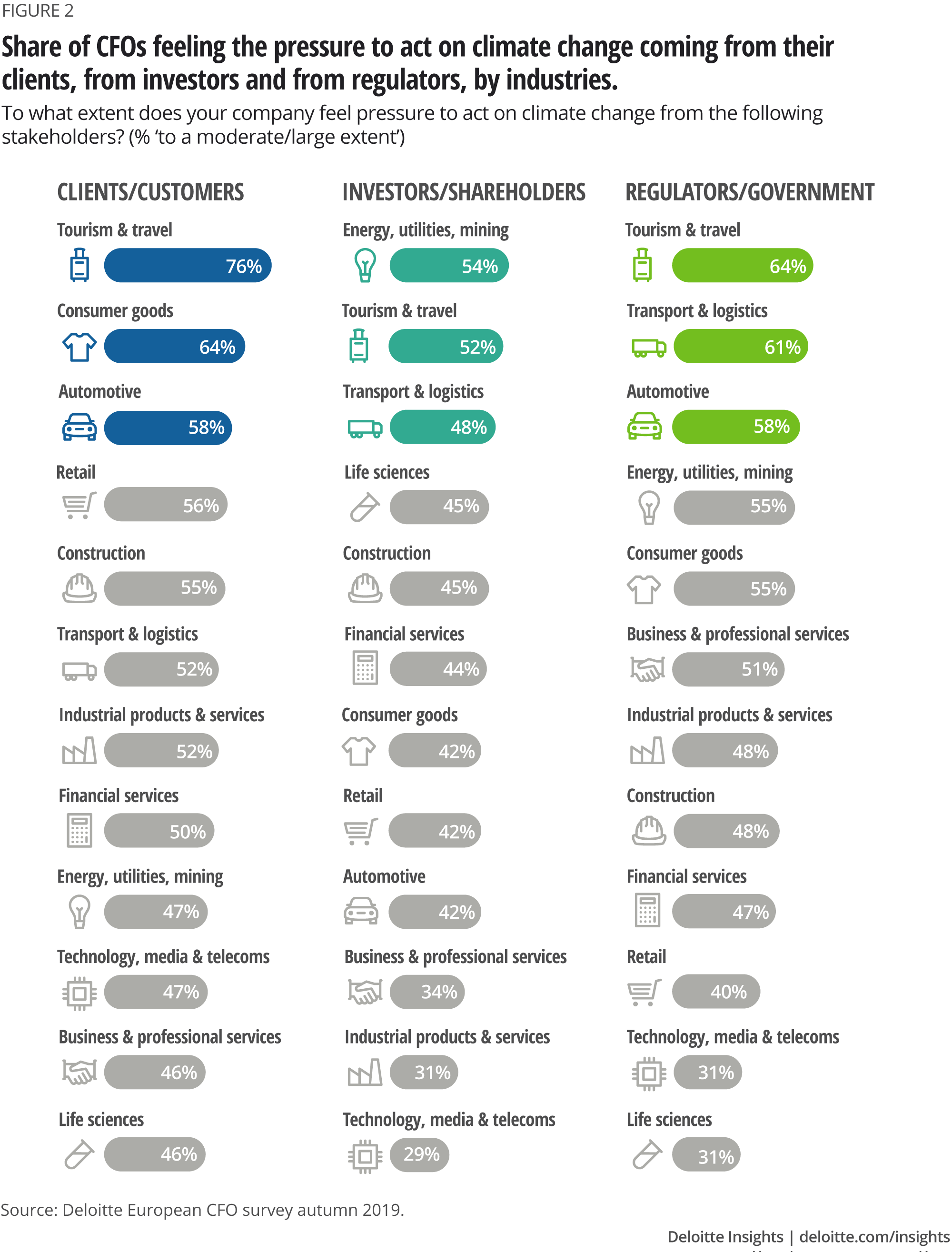

The pressure felt from different stakeholders also varies across industries. In tourism, automotive, consumer goods and energy and utilities, the share of executives reporting pressure to act is among the highest for each stakeholder group. There are some differences between these sectors, however, in the degree of influence coming from the various stakeholders. For example, in tourism, consumer goods and automotive, pressure from clients is felt more strongly. In energy and utilities the pressure comes more from investors and regulators (figure 2).

At the other end of the spectrum, the technology, media and telecommunications (TMT) industry seems at present to be flying under the radar when it comes to climate change. TMT executives do not feel particularly pressured to act from any given stakeholder, except their own employees, in part because the sector’s emissions are relatively low. But there is scope for TMT to do more to help tackle climate change. A joint study by the Global Enabling Sustainability Initiative (GeSi) and Deloitte shows that the digital capabilities of information and communications technology (ICT) can help deliver solutions to a broad range of sustainability challenges – and especially to climate change.11 Digital technologies can, for example, help decouple economic growth from resource consumption, enhance transparency and accountability on environmental impacts, and help to analyse and predict climate change developments.

3. How should corporate management respond?

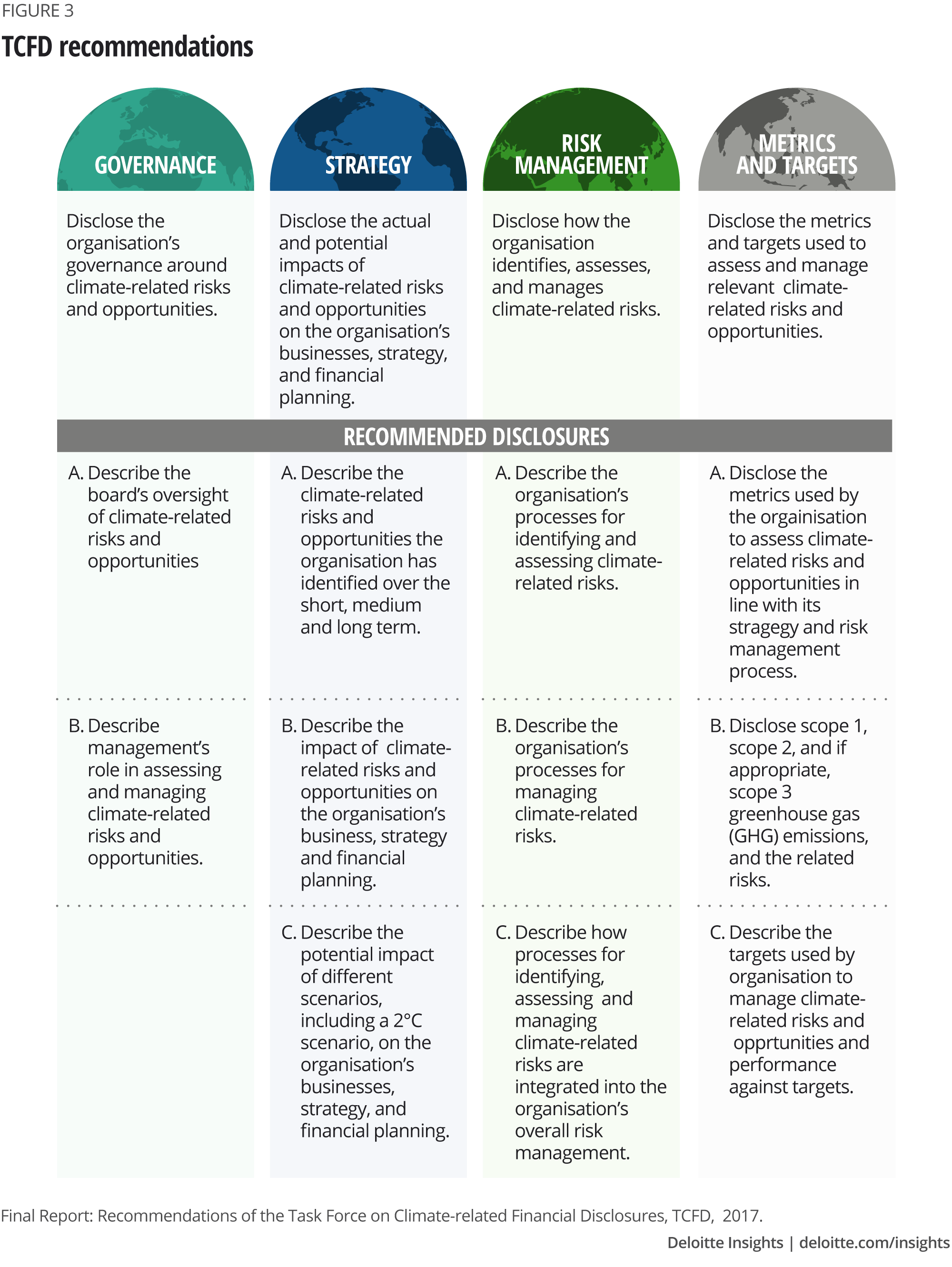

The TCFD defines four key management disciplines through which companies are expected to address climate change: governance, strategy, risk management, metrics and targets (figure 3).12 Enhanced disclosure in these areas will help investors and other stakeholders assess a company’s exposure to climate-related risks, and the quality of its response to them.

The TCFD’s recommendations are broadly applicable but have a particular focus on high-impact industries. These include banks, insurance companies and asset managers, who will need to deal with climate change-related risks in their portfolios. In the real economy, the sectors on which the TCFD focuses include energy, transport,, agriculture and forestry. Companies in these industries are particularly exposed and can expect to face increasing pressure to disclose how they view and deal with the impacts of climate change on their business models and value chains.

The willingness of companies to disclose climate change-related management activities and greenhouse gas emissions has grown rapidly in recent years. To date, more than 800 companies have signed up to the TCFD, thereby providing support to the idea of enhanced management and disclosures, although so far very few have actually delivered. Reporting of actual carbon emissions performance, however, has already come a long way. In 2019, almost 7,000 companies reported their emissions to the Carbon Disclosure Project (CDP), twice as many as in 2011.13

Yet, enhancing management and disclosures, and establishing risk assessments and targets will not by themselves suffice. More crucial are the actual actions companies undertake to reduce emissions and mitigate risks. This may include reorientation towards renewable energies and raw materials, a reduction in their reliance on scarce water resources or the protection of production sites from extreme weather by building dams or installing heat insulation. Seizing opportunities to deliver marketable solutions to climate change is another area of concrete, necessary, but also worthwhile action. This might include the development of less carbon-intensive products or of services that help people and economies sustain themselves in a world affected by climate change.

4. Start climate action by setting emission reduction targets

When it comes to defining a company’s response to climate change, it is helpful to be clear on what needs to be achieved. This could be done by setting targets for future carbon emissions, taking account of national and international emission reduction commitments, such as the Paris Agreement. While the agreement requires each country to outline and communicate emissions targets at the national level, companies can now derive scientifically their individual CO2 reduction targets, and bring them into line with the objectives set out in the IPCC climate scenarios.14 Thus, good practice means setting targets that define the company’s ‘fair share’ to the achievement of the Paris commitments and the pace of the transformation required to achieve these goals.

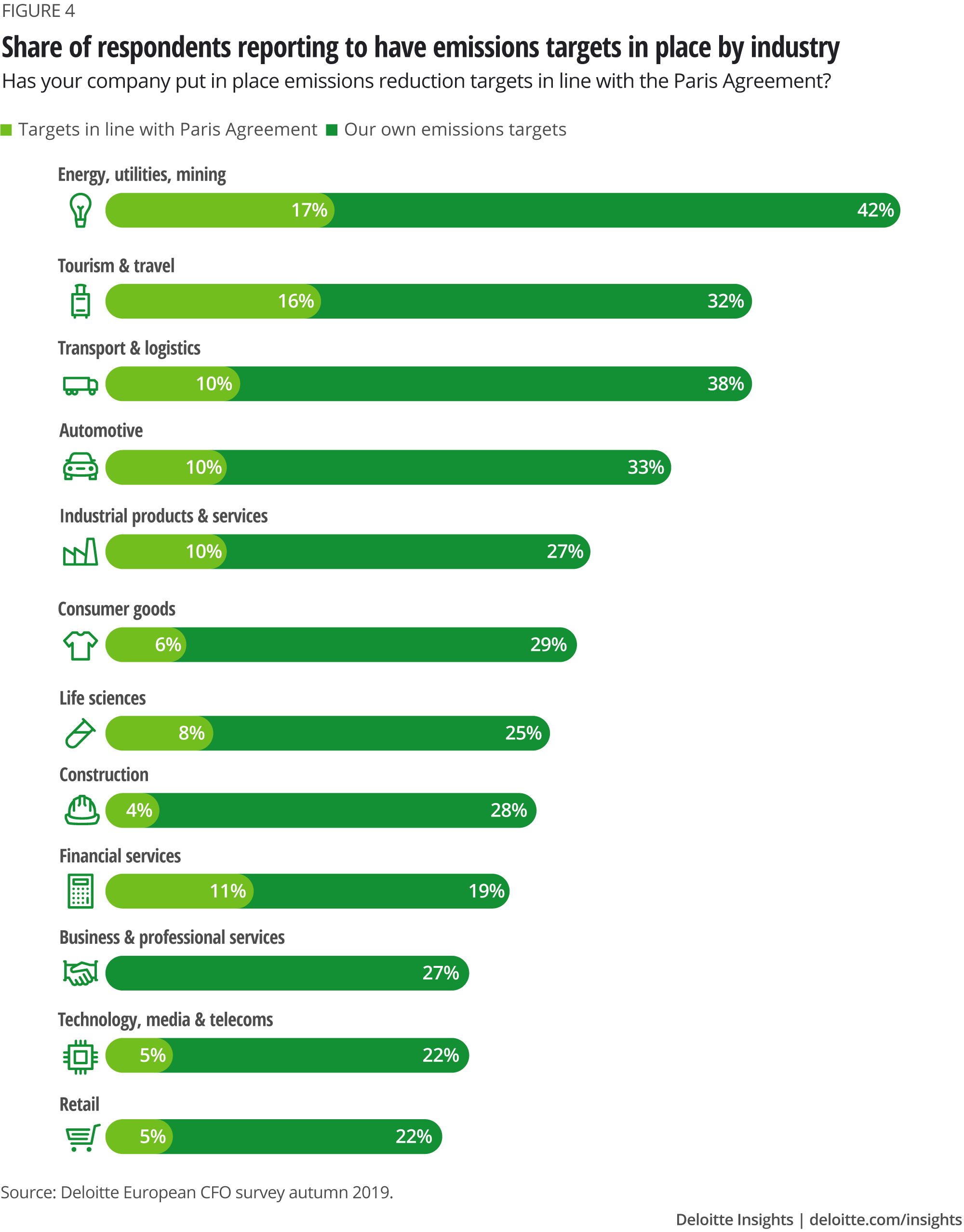

According to the results of the European CFO survey, however, a little less than 10 per cent of companies say they have set targets in line with the Paris Agreement. 27 per cent of companies have set autonomous carbon emission reduction targets. One in two companies have not set any target at all. Although the proportion of companies with some kind of emission targets in place rises when there is pressure from stakeholders, it remains below 50 per cent.

Commitment also varies across industries. The energy, utilities and mining sector is the only one in which a majority of CFOs report that they have targets in place (figure 4).

5. What are companies doing to combat climate change?

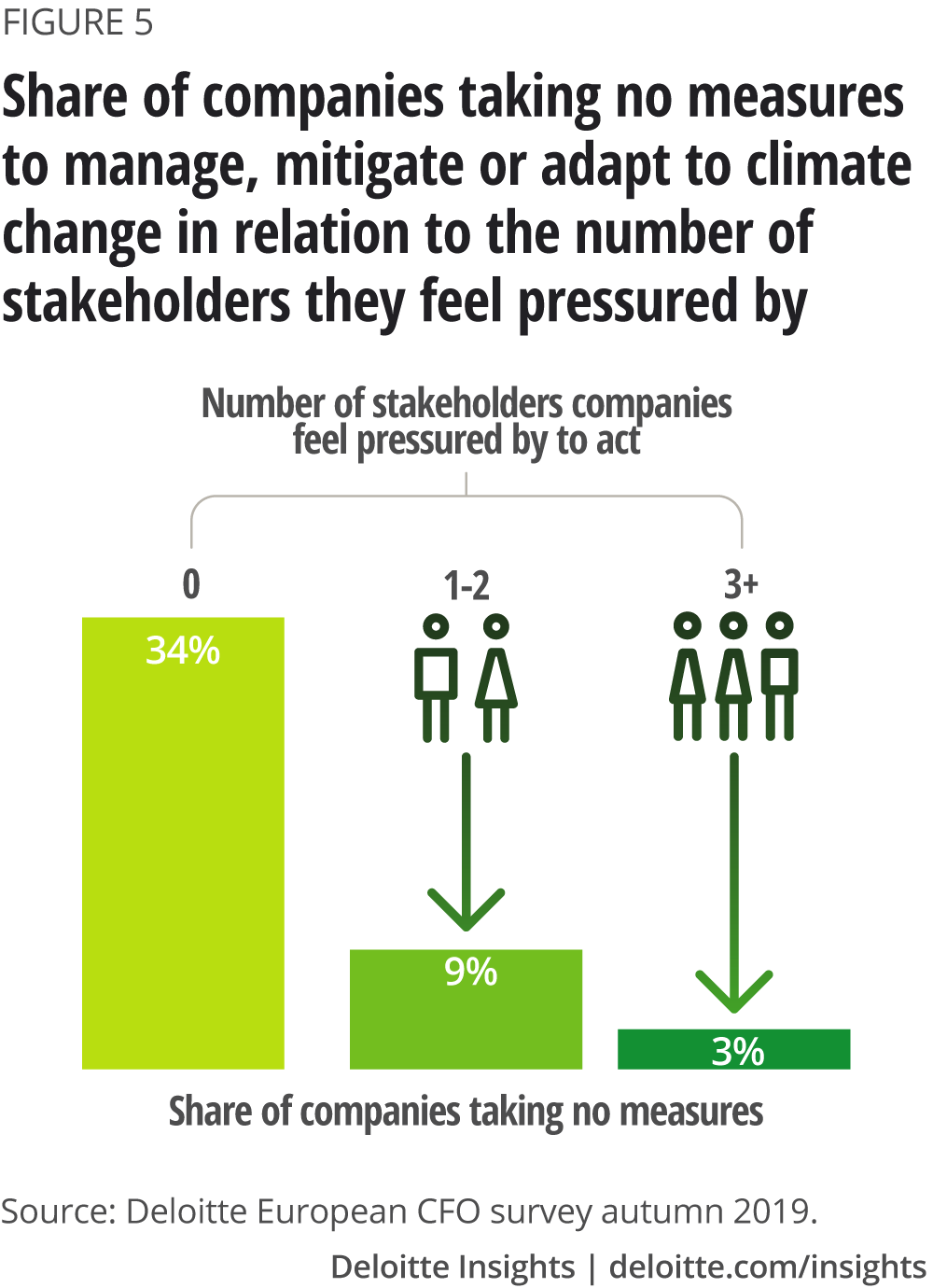

Stakeholder pressure leads to action. One-third of the companies that are not under significant pressure from any particular stakeholder say they are not taking any action to manage, mitigate or adapt to climate change. But in companies that feel pressurised by three or more stakeholders, only three per cent are failing to take action (figure 5).

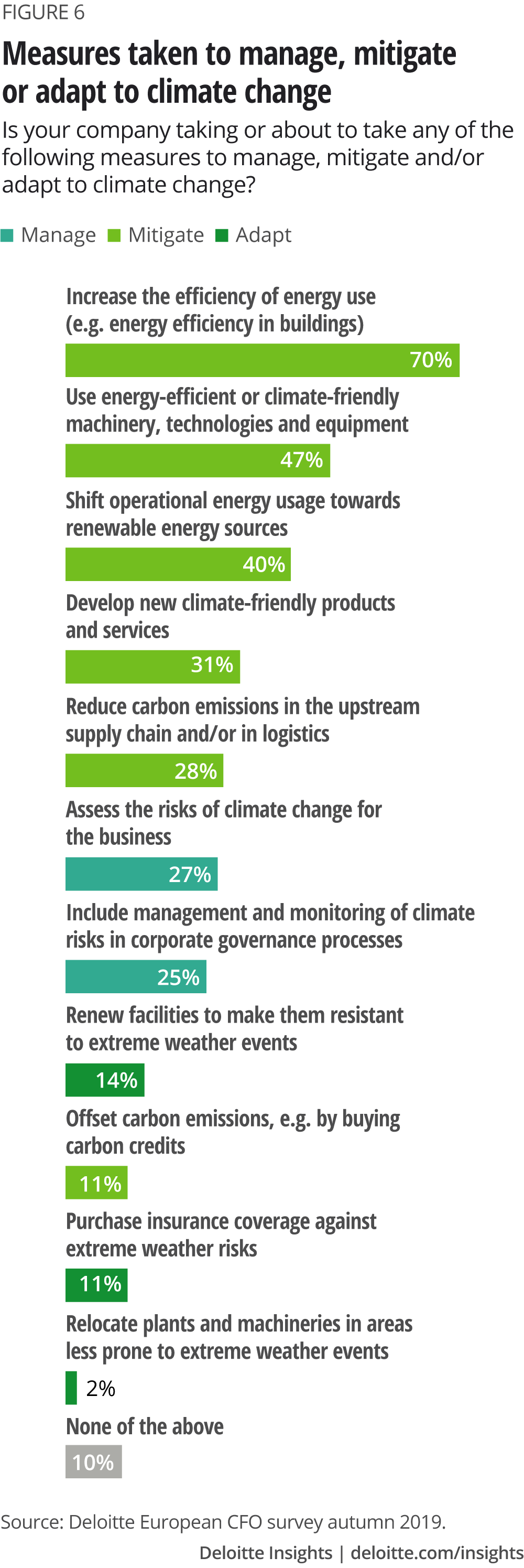

From what finance executives report, however, companies’ climate responses focus primarily on measures that have a short-term cost-saving effect. When it comes to the specific actions taken, most companies resort to increasing their energy efficiency and using more climate-friendly equipment (figure 6). These measures often benefit from government incentives and help to reduce corporate costs. Thus, companies are plucking the low-hanging fruit and reaping immediate cost benefits. Less prominent are longer-term measures that would generate revenues and more resilient growth by developing climate-friendly products and services.

Moreover, companies appear in general quite reluctant to engage with other companies within their supply chain to reduce carbon emissions. Only 28 per cent of respondents report doing so. Difficulties coordinating with other companies and probably a lack of any financial incentive may be behind this.

Few adopt a more systematic approach and properly assess climate-related risks or include them in their governance and management structure. Companies which report that they feel the pressure coming from investors are more likely to have included the management and monitoring of climate risks in their governance processes. This demonstrates that risk-aware investors can help to promote climate-related transformation in companies.

Overall, it seems fair to say that most companies are not taking into account the already foreseeable physical effects of climate change, nor are they undertaking significant measures to adapt. Companies may believe that climate change will have less impact in Europe than elsewhere, but, in that case, they are likely to be underestimating the risks to which they are exposed through their global supply chains and markets.

6. Preparing for a hotter environment

Taken together, the results reveal that many companies are increasingly under pressure from their stakeholders, and are beginning to react. However, the majority of action to date seems reactive and focused on short-term rewards and quick wins. A longer-term, strategic perspective on the risks and opportunities of climate change is rarely undertaken.

The following steps may help companies to get to grips with climate change:

- understand the risks climate change presents to the business, and the opportunities that may lie in becoming part of the solution

- assess the scale of necessary emission reductions, and the levers that are key to achieving them

- calculate how much will emission reduction and adaptation efforts cost?

- position the risks and opportunities of climate change within the governance structure to ensure a strategic measurable approach.

Climate change is transforming how consumers, employees and shareholders evaluate companies and interact with them. In some cases, this can lead to a real shift, where business models need to be reevaluated. Companies don’t only need to measure their exposure to climate-related risks and subsequently manage them, but also incorporate climate change in their strategic plans. Failure to do so will undermine the sustainability of their business.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.

Explore the CFO Collection

-

Building business resilience to the next economic slowdown Article5 years ago

-

Sustainability: Why CFOs are driving savings and strategy Article12 years ago

-

The journey to CFO Article13 years ago

-

Navigating change: How CFOs can effectively drive transformation Article12 years ago