Red Cross Regional Disaster Unit has been saved

Red Cross Regional Disaster Unit Using the ecosystem to help more people in need

07 March 2018

John Hagel III United States

John Hagel III United States John Seely Brown (JSB) United States

John Seely Brown (JSB) United States Maggie Wooll United States

Maggie Wooll United States Andrew de Maar United States

Andrew de Maar United States

For effective disaster relief, understanding local priorities is critical. How can a regional unit stay prepared and flexible? The Red Cross’s Regional Disaster Team of Central/Southern Illinois uses six of the nine practices in handling event responses as well as recruiting and training volunteers.

The American Red Cross aims to provide disaster relief and emergency assistance to those in need. For over 135 years, the organization has been “helping neighbors down the street, across the country, and around the world.”1 Operating a network of more than 600 chapters, the Red Cross relies on large numbers of volunteers to support its humanitarian relief efforts.

Since 2012, the Red Cross nationally has shifted from relying almost entirely on paid staff to managing a network of local volunteers with local chapters. In some regions, such as Central/Southern Illinois, this shift began earlier, in 2008, in part due to the influx of experienced volunteers who had joined the organization’s efforts in the weeks and months following Hurricane Katrina in 2005 and who wanted to continue their relationship with the Red Cross. The organization credits this shift with helping the organization provide more effective assistance to more people, faster, and with amplifying its positive impact in the communities it serves.

Learn More

Explore the practices and case studies

Read an overview of the opportunity

Download the full report or create a custom PDF

The Red Cross’s Regional Disaster Team (RDT)2 of Central/Southern Illinois has redesigned its responses to a range of events, from multifamily fires and tornadoes to flooding events. It has also been a leader in developing and leveraging its volunteer network to support disaster response. Across ever-changing circumstances, this workgroup has consistently helped more and more people per Red Cross employee across more events each year.3

The workgroup: Regional Disaster Team of Central/Southern Illinois

Local chapters and disaster units are often the most public face of the Red Cross, both for event response and recruiting and training volunteers. The RDT oversees a broad network of volunteers in Illinois, northeastern Missouri, and southeastern Iowa.4 The workgroup’s primary responsibility is to respond to events within its geographic region, although staff and volunteers are frequently called to assist wherever help is needed, across the country and throughout the world. Most recently, the organization deployed the workgroup to Florida and Puerto Rico following hurricanes Harvey and Irma.

The RDT meets our criteria for a workgroup:5

- Size: The RDT is made up of 10 staff members: four at the regional level and six assigned to specific chapters.

- Sustained involvement: Staff members are assigned to the RDT full time, filling roles that change depending on whether they are in-response or between responses. In a disaster response—what they refer to as “gray sky”—their job is to respond to the event. When not deployed, members are in standby, “blue sky” mode preparing for the next regional response. Members may spend some part of their time deployed apart from the workgroup to major responses in other regions, both to assist where there is a need and to develop additional skills.

- Integrated effort: During disaster response events, RDT members are working together, making decisions and carrying out activities that are interdependent and could not be accomplished individually. In between response events, although they are not all physically co-located, the members work together on preparedness as well as refining or developing their approaches, and training and developing volunteers and other resources.

This workgroup leads the delivery of the Red Cross’s Disaster Cycle Services in the region, including preparedness, response, and recovery programs to 78 counties in a region of more than 3 million people. The incident types to which the group responds are diverse: tornadoes, floods, earthquakes, house fires (both single and multifamily), manmade disasters, and acts of terrorism. Over time, the scope of its work has only expanded, with every year outpacing the prior one in terms of both number of responses and number of people helped.

In the aftermath of a disaster, the RDT aims to be an essential, indispensable resource for those affected, and workgroup members tend to pride themselves on being there to answer the call. The organization provides (in order of priority) shelter, food, financial assistance, and information—reconnecting people who have been separated in disasters. It considers its efforts complete when a sense of normalcy has been reestablished—even if “normal” has been forever changed by the disaster.

No matter what type of disaster drives an RDT response, the group is committed to addressing basic human needs and helping as many people as possible, as quickly as possible. That means maximizing its impact with its available resources, in large part by first offering urgent short-term services, then linking people with ongoing support from other resources, institutions, and facilities that support long-term recovery.

A key aspect of the RDT’s approach, and one on which members have increasingly focused over the years, involves using local volunteers, rather than by people brought in from the outside, as key members of any response effort. More and more people have volunteered over the past several years, and the RDT currently has around 800 disaster volunteers in the region. In fact, recruiting, onboarding, training, deploying, assigning, and otherwise supporting volunteers—in blue- or gray-sky situations—is a key part of the workgroup’s efforts.

Initially, this volunteer-centric model was driven by several regional disasters combined with the fortunate legacy of having a good base of volunteers with experience from Katrina recovery efforts. Local volunteers are usually personally invested in their communities and have a solid understanding of what recovery or “normal” looks like and what a community might prioritize. On a tactical level, locals are more likely than others to know how to get around the affected area, where to get supplies, alternate routes, whom to call to get access to a church or school, and have firsthand knowledge of other resources that might be available to speed up and improve responsiveness. Over the years, the RDT has developed “career” or advancement models for volunteers so that those who want to learn and progress have opportunities for training and deployment. This has resulted in a base of volunteers with specialized skills, including some that specialize in relief operations, that the workgroup can tap for input and assistance.

The results: Helping more people

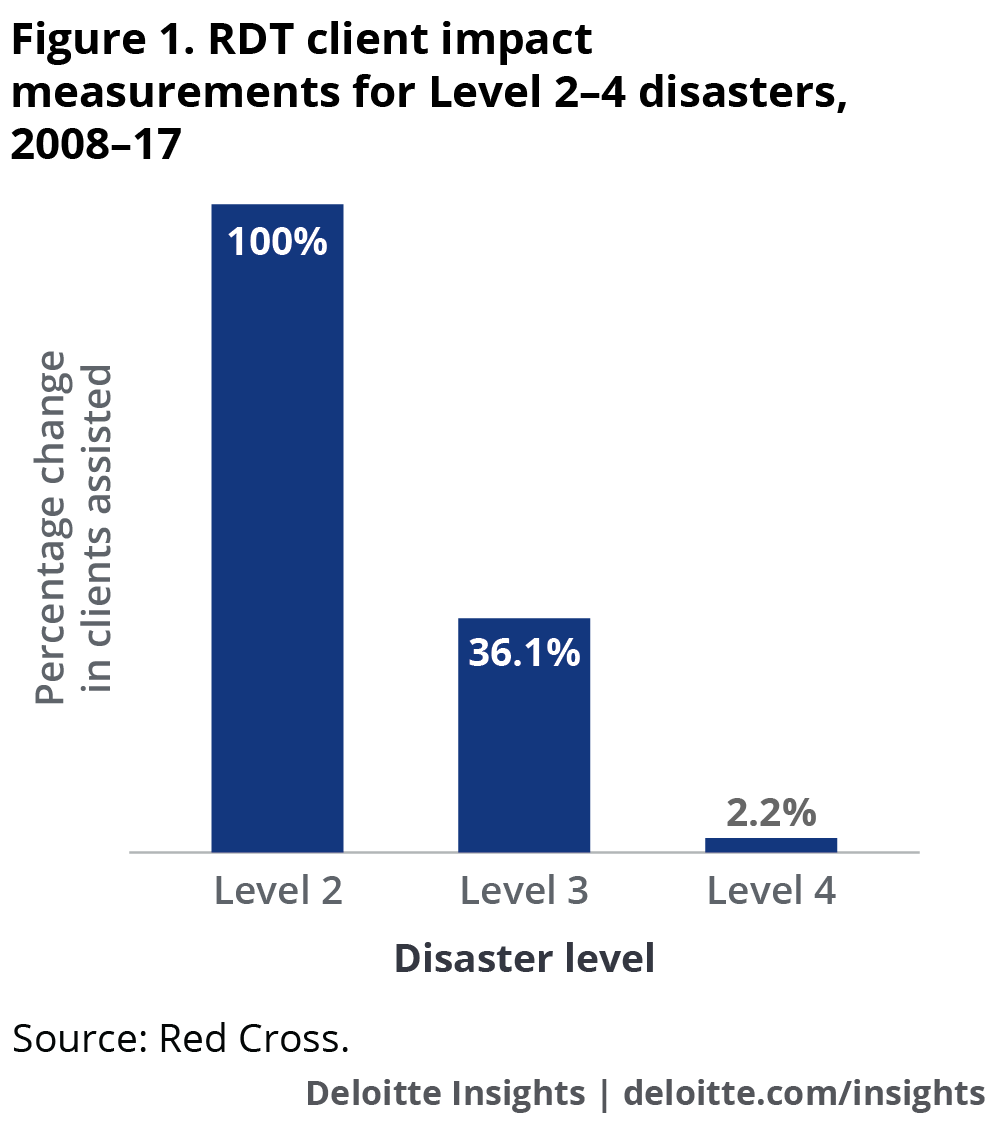

The Red Cross categorizes every disaster—from apartment fires and winter storms to tornadoes and hurricanes—on a scale of 1 to 7, with 7 being the highest. Categorization is based on the budget required at the ground level and indicates both the complexity of the response and the resources required.6 In the Central/Southern Illinois region, the RDT has seen nothing larger than Level 5. Thanks largely to continually improving its approach both in responding to disasters and in developing capabilities in between disasters, the workgroup has been able to assist more people in need per employee, improving positive impact across all event categories—even complex Level 4 disasters. The improvement has been most notable across Level 2 events, where, thanks to the ability to deploy a broader range of volunteers, RDT was able to assist twice as many people per paid staffer in 2017 as it did in 2008.

What the numbers don’t show clearly, though, is the quality of a response and any enduring impact that preparedness and development of local volunteers can have on a community. It isn’t just about the total number of people helped—after a disaster event, the RDT is committed to helping all of the affected people faster and better, since time and elements of normalcy are key when one’s life is disrupted. Regional disaster officer Alyssa Pollock says, “We’re really proud that during this time as we’ve served more and more people in need, in more events, really leaning on our wonderful volunteers, that we believe we’ve been able to do this without diminishing the quality of our response.” Although the group lacks sufficient data to measure it, the RDT is concerned with minimizing the “time to peak service” as a proxy for not reaching those most in need but being on the ground and reaching everyone affected.

Practices in play

In its work, the Red Cross’s Regional Disaster Unit of Central/Southern Illinois uses six key, intersecting practices: Commit to a shared outcome, Maximize the potential for friction, Bias toward action, Seek new contexts, Prioritize performance, and Reflect more to learn faster.

Commit to a shared outcome

As an organization with a century-old history of responding to disasters,7 the Red Cross is committed to a shared outcome—helping people recover in the most effective way possible. One thing that’s changed in recent years, across the organization, is how that goal is achieved. Today, instead of bringing in large teams of people from outside a disaster-struck area to strive toward a single theoretical goal, the nonprofit often brings in smaller teams of experts, then leverages local volunteers whose vision of the shared outcome is likely strongly connected to the locality and community.

Perhaps there’s no greater sign of this commitment to a shared outcome than the workgroup shifting its entire organizational structure to respond to different disaster types. In most cases, this means RDT members taking on a wide range of roles—often humbler than their titles may indicate—in order to more effectively serve people in need.

Commitment to a shared goal means putting a priority on achieving that outcome—even when it means stepping out of the way to let others provide a solution. For example, in large-scale disasters that require food and shelter services, the RDT might turn to a local jail or prison that already has an established infrastructure to provide meals and laundry service. Or the workgroup might look to local fish and wildlife departments to assist in sheltering pets and other animals.

One theme that RDT workgroup members highlight time and again is the importance of having great relationships with partners. Instead of reinventing the wheel, they strive to quickly and easily leverage the capabilities of others to amplify their own response efforts so that a shared outcome can be achieved as soon as possible and with a higher level of service. In a large disaster response, for example, when other response agencies are involved, the RDT might focus on providing food and shelter, while the Federal Emergency Management Agency might offer financial assistance.

Maximize the potential for friction

It may sound counterintuitive, but in many ways, the RDT maximizes the potential for friction with every disaster response. To better respond to each incident it is called to, the workgroup employs two operating models: blue-sky and gray-sky. Transitioning between these modes comes with the potential for friction, but it seems to make the whole organization more effective.

In standby mode, the RDT operates on the blue-sky model, with a set organizational structure and certain titles and responsibilities. During disaster response, it shifts to gray-sky mode, reshuffling the organizational hierarchy as needed, in a modified form of an incident command system. Staff roles and responsibilities can shift dramatically: For example, a staff member who specializes in tornado response would act as incident coordinator when a tornado strikes; when responding to a flood, she might be assigned a far lower-level task, such as distributing water. Regional specialization is also a factor. Someone who led a hurricane response effort in Florida might not lead a tornado response effort in central Illinois, since the disasters demand fundamentally different types of response.

Assigning staff of varied experience to different roles for different disasters—in essence, making roles context-dependent—can increase the potential for friction by switching up the relationships between members and removing a layer of authority or expertise they might have in other aspects of the job. This discomfort can cause tensions around how to approach problems or how tasks get done, but it can also bring in more perspectives and create a well-rounded and capable team of responders who are agile in their roles and relationships and adept at supporting each other. The members seem passionate about helping those in need over time as well as in the moment. They often embrace and even seek out opportunities to deploy in different roles, including out of region, as a way to learn more and develop new skills.

At the same time, the RDT workgroup is coordinating volunteers who often find themselves in different types of roles than they are accustomed to in their day jobs. The focus on training and developing volunteers has been a powerful force for attracting a certain type of volunteer with a passion to get better and better at making an impact and eager to gain experience and leadership opportunities. These volunteers typically bring in additional perspectives and knowledge, as well as a vested interest in the community, that can increase the potential for friction as well.

Bias toward action

For the RDT, achieving results can be more important than sticking to process. The workgroup aims to never let organizational processes or structures get in the way of fulfilling its mission. The RDT empowers frontline employees and volunteers to make critical decisions in a wide range of situations. With the guidance to always try to do the right thing for clients and avoid doing anything illegal or immoral, the staff is trusted to make the right call in the moment.

When it comes to emergency response, it’s often impossible to get 100 percent of the information needed to make a critical decision in the timeframe available. Take too much time to make a decision, even if it’s a great one, and it may be too late to make a difference. In the aftermath of any disaster, for example, efficacy typically takes precedence over efficiency. The first priority is to provide food and shelter; if people are going to starve or die for lack of those things, delivering resources in a less than ideal way is better than delivering them later in a more efficient fashion.

Knowing this, the RDT builds risk tolerance into its decision-making process. Workgroup members use the 30/70 rule to help boost their decision-making velocity: Once you have 30 to 70 percent of all the information you need to make a decision, take action. Less than 30 percent of total information is considered too little to make an informed decision, while waiting for more than 70 percent could take too long and render any decision moot. For example, with major winter storms, the group always gets a lot of stranded travelers, but a storm event might span all 78 counties, meaning that by the time members get more accurate information, it’s too late to try to get resources everywhere they are needed. Members, then, talk with state patrol and use their own experience from previous storms to pre-stage people and supplies in likely areas in advance.

Another essential practice that biases the workgroup toward action is fluidity, the ability to make decisions—and to reverse them. RDT leaders and volunteers know that the majority of their decisions are flexible and reversible, should they need to change course as the situation evolves. This is especially valuable for decisions made with little information; as clarity increases with time, staff can modify and adjust responses as needed. Team members don’t want anyone to feel compelled to execute just for the sake of following through on a previous commitment—once a situation, or the understanding of it, changes, staffers are expected to change their response accordingly.

For the RDT, fluidity is most required when it comes to providing shelter. For example, depending on the anticipated size and scope of a major storm approaching a region, the workgroup may preemptively open up shelters to assist those in need. Since providing a shelter requires significant time, money, and resources, if the RDT opens a shelter and sees few people using it, staffers might move people to a hotel to avoid running an expensive operation at less than 25 percent capacity. Embracing and expecting fluidity in all decisions makes it possible to provide more personalized services—and ensures that the organization’s resources are used effectively.

To privilege action over inaction, RDT employs a practice called “go until no”: At smaller-scale events, for example, key frontline volunteers are empowered to act on the agency’s behalf to assist those in need—without requirements to consult local office leadership. For example, when there’s a single-family fire in the middle of the night and the Red Cross is called to provide assistance, it’s typically a volunteer coordinator who handles the request from start to finish, responding to the scene and providing as much assistance as necessary. Leadership at headquarters merely learns of the response the following morning, as part of a daily briefing.

This kind of volunteer autonomy isn’t put in place for large-scale disasters, or even some multi-home fires, but using it for small-scale events can help the organization enhance readiness for major events instead of routinely being pulled into minor incidents that qualified volunteers can handle. As incidents become more severe and affect a much larger area, one or more staffers trained in emergency management typically come in to manage the response.

Prioritize performance trajectory

Red Cross’s commitment to providing basic human needs drives the RDT to focus on mass care, to ensure that all clients have water and are fed and sheltered. Only after that does the group look to provide individualized services, such as financial support or assistance with finding long-term housing. Similarly, the workgroup has to prioritize both who it helps and where—not easy decisions when many are suffering. As a guiding principle, the RDT prioritizes assisting areas that have been hit hardest and have the greatest need, rather than just assisting the greatest number of people in need. While this may seem intuitive, it often increases the complexity of the response, since such areas may lack running water or electricity and could be completely inaccessible due to flooding or damaged infrastructure.

Seek new contexts

RDT members are constantly challenged to step outside their comfort zone—be it one of region or experience. However, they also recognize that when people leave their home region, they have an opportunity to discover new ways of working and being effective. Explains regional disaster officer Alyssa Pollock, “Every disaster I learn something, and by deploying outside the region, I’ve learned quite a lot. I was able to see how things could work more effectively, even during our blue-sky, steady-state operations—things I wouldn’t have otherwise known existed.”

In exposing themselves to multiple contexts, staffers are able to see what’s worked and what hasn’t in each—approaches they may not have considered in their home state, from human resources processes to team leadership styles to tactics for sheltering survivors. This exposure can help them continuously improve Red Cross operations as they move forward. Explains Pollock, “A staffer might think, ‘I’ve seen this service delivery work really well during my response to Alabama; we should try to implement something similar in our region’ or, ‘I liked the way they ran their meetings and kept people really engaged—we should try to do that.’”

Even when seeking new contexts isn’t so straightforward, it can still yield results. One of the trends with which the RDT contends is a growing number of emotional support animals, which provide comfort for clients but can create issues with shelter partners, which often lack facilities for animal care and toileting. The solution: temporary kennels that give clients access to their animals in a controlled and appropriate environment.

And even as the team continues its learning, at the RDT every disaster has its own context. This attitude is reflected in one of the workgroup’s mottos: “If you’ve seen one disaster, you’ve seen one disaster.” It’s just one hallmark of a culture of endless and continuous learning, in which all staff and volunteers are encouraged to broaden their experiences by either volunteering to assist with operations outside of their home region or expanding their repertoire of volunteerism with other agencies. Seeking outside context tends to challenge existing points of view, build experience, and surface new ideas and innovations.

Reflect more to learn faster

The RDT is committed to learning, and to the continual improvement of its people and organization. One method the workgroup employs is internal after-action reviews—for each response, discussing what went well and what could have been done better. Workgroup members seek out not only staff opinions and insights but feedback from clients and partners. The goal is to put that feedback into practice, prioritizing the most actionable issues.

In a recent after-action review following an RDT deployment to a large flooding incident, for example, one important piece of feedback was that home offices found it difficult to connect with anyone at the site, especially the event coordinators. The coordinators, dealing with an overwhelming degree of chaos, had to prioritize more pressing work. Meanwhile, members of the public were asking home offices for status updates on the response, and some wanted to help in the relief effort—but the home offices had no information for them. More importantly, they were unable to pass along valuable help to the coordinators.

In its after-action review, RDT leaders decided that in all future operations, the group would institute a chief-of-staff role; the chief would deploy to the disaster area with the relief operations director, serving as liaison with both home office operations and the coordinator. Less pressing issues could be addressed when conditions allowed. Implementing feedback from after-action reviews in such ways also puts into practice the idea that every team member has a voice and can enhance the effectiveness of the whole organization.

For the RDT, reflection doesn’t happen solely after an event. Preparation and response plans for potential problems—“pre-mortems”—allow the group to provide support as quickly as possible in case of actual disasters. In August 2017, for example, tens of thousands of people traveled to southern Illinois to view a solar eclipse. In the weeks leading up to the event, RDT leaders pre-planned for how a mass influx into the region could affect the group’s operations and ability to respond should a natural disaster or other large incident occur. On a smaller scale, it also addressed the potential impact on its ability to find shelter for survivors of fire damage, given that local hotels were oversold. The RDT asked local shelters, such as churches and schools, to be ready to assist. Though all went smoothly, the preparations likely helped, both in the moment and in terms of ongoing learning. The workgroup can translate much of this into how it plans for stranded travelers, stands up shelters, and moves staff around in future major storm events.

At a national level, the Red Cross is also constantly gathering feedback and using reflection to support learning. For example, after multiregion disasters (such as the hurricanes and wildfires in fall 2017), the national headquarters has an independent team conduct detailed interviews with volunteers and employees who served in leadership roles during that response. They also use partner and client surveys with open-ended questions to gather feedback from other stakeholders and distribute electronic surveys to every volunteer and employee who worked on the response. In the after-action reviews conducted after major responses, most of the conversation is qualitative in nature. Priorities for follow-up and action items are generated from these conversations and used to drive program improvements and improve internal coordination. The conversations and feedback are documented and discussed to improve services and internal coordination on the next response.

Looking at trends in its disaster response history, including both metrics and survey responses, the RDT found that every year has outpaced the year before, in terms of both number of responses and people helped. This information supports plans to enhance organizational readiness in areas including setting realistic expectations with partners so they know when and where food and shelter services are likely to be needed, ensuring the provision of needed training and accurate deployment of disaster experts, and modernizing technological infrastructure to better interact with clients via mobile devices.