Passion at work has been saved

Passion at work Cultivating worker passion as a cornerstone of talent development

08 October 2014

John Hagel III United States

John Hagel III United States John Seely Brown (JSB) United States

John Seely Brown (JSB) United States Alok Ranjan India

Alok Ranjan India Daniel Byler United States

Daniel Byler United States

By cultivating the traits of worker passion in their workforce, organizations can make sustained performance gains and develop the resilience they need to withstand continuous market challenges and disruptions.

Executive summary

Up to 87.7 percent of America’s workforce is not able to contribute to their full potential because they don’t have passion for their work. Less than 12.3 percent of America’s workforce possesses the attributes of worker passion. This “passion gap” is important because passionate workers are committed to continually achieving higher levels of performance. In today’s rapidly changing business environment, companies need passionate workers because such workers can drive extreme and sustained performance improvement—more than the one-time performance “bump” that follows a bonus or the implementation of a worker engagement initiative. These workers have both personal resilience and an orientation toward learning and improvement that helps organizations develop the resilience needed to withstand and grow stronger from continuous market challenges and disruptions.

Unfortunately, not only do many companies not recognize the value of worker passion, they view it with suspicion. Many work environments are actually hostile to it. The types of processes and policies designed to minimize risk taking and variances from standard procedures effectively discourage passion. Passionate workers in search of new challenges and learning opportunities are viewed as unpredictable, and thus risky.

Learn more

Read the related press releaseLast year, our report Unlocking the passion of the Explorer explored a variety of business practices and policies that may encourage or discourage worker passion.1 It also introduced archetypes for those workers (currently 87.7 percent of the US workforce) who do not possess all of the attributes that define worker passion but have the potential to develop them. We made the case that companies should do more through redesigning the work environment to elicit and amplify worker passion in order to improve learning opportunities and ultimately drive sustained performance improvement.

This report uses new survey data to debunk five myths about passionate workers and offer predictive evidence of how companies can cultivate passion in the workforce. Specifically, this report reveals the unexpected profile of passionate workers, their motivations, and the reasons they are so important for a resilient workforce. It also identifies tactics for finding and developing these qualities within the workforce, including tangible steps for how companies can create work environments that unlock worker passion at all levels of the existing workforce.

Understanding the passion of the Explorer

A passion for the business of wine

“I don’t work a day in my life,” says Christopher Strieter, cofounder of Senses Wines, a small-batch producer of West Sonoma Coast Pinot Noir and Chardonnay, and sales manager at Uproot Wines, a VC-backed direct-sales wine company focused on the customer experience. Strieter describes himself as always looking for a challenge and enjoying difficult problems, a disposition that led him first to major in mathematical economics and physics at Harvey Mudd College—he wanted to travel into space and make an impact. For Strieter, the wine business requires simultaneously solving the science of growing, the art of making, and the business of selling: “I’ve tried to pick each of my jobs based on an area of the business I need to learn more about, and I learn by being immersed in it.” Strieter doesn’t take any jobs that he can’t learn from. He says, “The wine industry tends to attract people who are just really into wine; consequently, most jobs don’t have to pay very well. So my goal for each job was also to keep meeting more people I could learn the business from—everything in the wine industry is based on relationships.”

“The credit belongs to the man who is actually in the arena, whose face is marred . . . ; who strives valiantly; who errs, who comes short again and again, because there is no effort without error and shortcoming; but who does actually strive to do the deeds; who knows great enthusiasms, the great devotions; who spends himself in a worthy cause; who at the best knows in the end the triumph of high achievement, and who at the worst, if he fails, at least fails while daring greatly, so that his place shall never be with those cold and timid souls who neither know victory nor defeat.2” —President Teddy Roosevelt

Strieter’s interest in wine was sparked by a serendipitous relationship that led to an internship and deep mentorship that stretched over several years and afforded him an opportunity to experience many aspects of the wine industry up close and firsthand. The knowledge, energy, and passion of his mentor were inspiring: “A light went off that creating a business can be so much fun.” Upon graduating, Strieter decided not to follow the typical path of his classmates into tech or finance jobs, so he went into a master’s program to buy breathing room to consider what it was he was preparing himself for. At the end of that time, with a six months’ grace period on his student loans, he took a “harvest internship” working in a wine cellar. He hasn’t looked back.3

Defining worker passion: Why the passion of the Explorer matters

Your dream employee: She searches for new, better, solutions to challenging problems, takes meaningful risks to improve performance, performs at a higher level of performance with each passing year, works the hours needed to get the job done, is well connected to others internally and externally who work in related domains, and cuts across silos to deliver results. If this worker, who exhibits all the attributes we define as the “passion of the Explorer,” works for you, congratulations. Unfortunately, she’s a very rare person and also more likely to leave your firm. Neither the potential benefits of such an employee nor the risk of losing her is likely to show up in the annual talent or engagement survey.

When we talk about “worker passion,” “passionate” workers, or “Explorers,” what we mean is a worker who exhibits three attributes—questing, connecting, and commitment to domain—that collectively define what we have termed the “passion of the Explorer.” We will use these terms interchangeably throughout the paper.

The concept of worker passion, which we describe as the “passion of the Explorer,” is different from engagement. Employee engagement is typically defined by how happy workers are with their work setting, coworkers, organization-wide programs, and their overall treatment by their employer. Employee engagement is important, and improving it typically will give a firm a bump in performance. But engagement is often a one-time bump; employees move from unhappy to happy, bring a better attitude to work, and possibly take fewer sick days. However, workers who are merely engaged won’t actively seek to achieve higher performance levels, to the benefit of self and firm; passionate workers will, though.

Explorers are defined by how they respond to challenges. Do they get excited by, and actively seek out, challenges? How do they solve problems? How do they learn, develop skills, and build their careers over the long term? How do they interact with others to pursue those goals? Through their behaviors, Explorers help themselves and the companies they work for develop the capabilities to constantly learn and improve performance. Rather than a one-time performance bump, Explorers deliver sustained and significant performance improvement over time.

Continually improving performance is critical in a global business environment increasingly characterized by mounting performance pressure, constant change, and disruption, where companies will have to take on new roles, develop new capabilities, and fundamentally shift their relationships with customers and partners. Exponential improvements in the cost/performance of the core digital infrastructure—computing, storage, and bandwidth—coupled with the general trend toward public policy liberalization have unleashed forces that are impacting today’s individuals, companies, and markets. We call this phenomenon the Big Shift.4 While individuals benefit from these trends by gaining increasing power as both consumers and talent, companies are increasingly coming under pressure. Corporate return on assets (ROA) for US companies has dropped to about a quarter of its 1965 level. Competition has increased, and it is getting harder for businesses to maintain leadership positions. In this environment, talent is the only asset that has the potential to continuously appreciate. Companies need nimble workers who challenge the status quo, pursue improved performance, and learn from market forces and trends around them. These workers are resilient. They do not crumble under the pressure of the rapidly changing world. Instead, they view challenges as opportunities to learn and improve; they get stronger from these opportunities.

Explorers are uncommon in the US work environment, but many potential Explorers are “hiding,” discouraged by corporate processes and structures focused on standardization, predictability, and meeting the plan. However, every business has this type of worker. Businesses can learn to identify Explorers within their workforce and create work environments that elicit the Explorer behaviors in all workers. This is essential to surviving and thriving in the era of the Big Shift.

What is “domain”?

We use “domain” to mean an area of expertise, a specialization, or a market on which an individual focuses. We often refer to industries to capture the breadth of possibilities for domain, but an individual’s domain rarely aligns with industry SIC/NAICS codes or standard functional descriptions. For some, domain may be narrowly defined. For example, one person might be focused on making an impact in health care broadly, while another might focus on making an impact in the treatment of dermatological diseases. Another individual may focus on establishing and growing virtual communities—not a function per se—within large companies in unrelated industries.

Because the concept of domain is somewhat nebulous, it is difficult to convey it as a question to survey respondents. To simplify, we asked respondents about their commitment to their industries, recognizing that commitment to industry does not capture other possible domains such as market or area of expertise. However, we felt that the term “industry” would be most recognizable to our survey audience and capture the majority of the passionate. To test this assumption, we relaxed our filter to include those who indicated a desire to make an impact on their functional area, and the proportion of Explorers in our sample only increased slightly, to 13 percent from 12.3 percent. In future years, we will continue to refine our understanding of commitment to domain and improve how we test for it in a way that limits confusion for participants. Any additional thoughts or suggestions on this topic are welcome; please contact the Center for the Edge.

The attributes of worker passion

The passion of the Explorer is defined by three attributes: commitment to domain, questing, and connecting. Each of these attributes leads to behaviors that drive sustained performance improvement and help people integrate knowledge from professional networks and lessons from difficult challenges into a disciplined commitment toward making an increasing longer-term impact.

Commitment to domain. Long-term commitment can be understood as a desire to have a lasting and increasing impact on a particular domain and a desire to participate in that domain for the foreseeable future. Commitment to domain helps individuals focus on where they can make the most impact. Having domain context enables an individual to learn much faster, allowing for cumulative learning. This commitment, however, does not imply isolation or tunnel vision. Quite the opposite: These individuals are constantly seeking lessons and innovative practices from adjacent and new domains that have the potential to influence their chosen domain.

Commitment to domain is important because it can carry an individual through the inevitable bumps and disappointments that come, even in good work environments, over the course of a career. For Molly Hoyt, a program manager for a green power initiative at a major utility provider, commitment to green energy allows her to persevere in the face of a multistage, multiyear process that involves numerous regulatory hurdles and sometimes challenging negotiations with stakeholders. “I am so lucky to get to do this,” says Hoyt. “Where else could I make a bigger impact on sustainability with my product development expertise than bringing green power to one of the largest customer bases in the country?”5

Some industries or specializations may more naturally foster a resilient commitment. For example, Malay Gandhi, managing director of Rock Health, a digital health incubator, notes that the incubator’s portfolio has less turnover than originally anticipated. He attributes this to the various entrepreneurs’ commitment to improving peoples’ lives, often through a specific area of health, and often because of a personal connection to illness or suffering. This deep commitment will cause individuals to work harder and persevere longer in the face of obstacles and setbacks.6 The deep commitment to ever-increasing performance impact within the domain also lends itself to a willingness to step back—even to the point of starting over—to reframe not just an approach but, more radically, a company’s market assumptions and its entire basis of competition. This degree of unlearning and reframing is not comfortable for most people, but those with a deep commitment to domain are more disposed to embrace it in pursuit of making a larger impact. They are focused on performance trajectories. If they start to see performance level off or decline, they are deeply motivated to reassess their approach in order to continue to increase their impact.

About the data: Survey and interviews

In fall 2013, to explore how the attributes of the Explorer exhibit themselves in the workforce and how they are changing, the Deloitte Center for the Edge surveyed approximately 3,000 US workers (working more than 30 hours per week) from 15 industries across various job levels (senior management, middle management, and front line). This large sample size allows us to detect relatively small differences between different populations and gives us confidence in our results. Additionally, many of the findings in this report were made using predictive analytic techniques, making them more durable than traditional descriptive statistics.

Data don’t tell the whole story. To help us calibrate our understanding of the data, we selected a set of individuals from within our personal networks who we believed possessed the attributes of the passion of the Explorer and who were not CEOs or freelancers. We asked them to take the survey and participate in an interview. Interestingly, of the 10 individuals selected, only three, ranging in age from the mid-20s to the mid-60s, actually had all of the attributes of the passion of the Explorer. The other seven, all high performers who express a love of their jobs and who add great value to their organizations and teams, each were missing one of the three attributes of the Explorer. In particular, four lacked commitment to a specific industry or sector. For the most part, they were committed to something broader and more aligned with personal values than making a significant and increasing impact on a particular domain.

One theme that emerged was that passion can surprise a person. All of our subjects over the age of 30 told stories of starting down one path that they believed they were very interested in and then discovering—through serendipity, mentorship, and work opportunities—what they were really passionate about. Another common theme was that an intellectual interest or ideal did not always translate into the type of day-to-day work that engaged an individual’s passion. This balance varies by personality, but the conclusion is clear: The actual work matters as much as does the organization, the work environment, and the impact of the work.

Questing. The questing disposition drives workers to go above and beyond their core responsibilities. Workers with the questing disposition constantly probe, test, and push boundaries to identify new opportunities and learn new skills. Resourceful and imaginative, they experiment with novel ways of using the available tools and resources to improve their performance. These workers actively seek challenges that might help them achieve the next level of performance. If they cannot find the types of challenges that generate learning, individuals with a questing disposition are likely to become frustrated and move to another environment (such as a new team or organization) that does offer these opportunities.

Connecting. The connecting disposition leads individuals to seek out others to help find solutions to the challenges they are facing. Although networking—connecting with and learning from others—is commonly understood as an effective way to advance, those with a connecting disposition seek deep interactions with others in related domains to attain insights that they can bring back into their own domain. Workers driven by a connecting disposition build connections, not to grow their professional networks but to learn from experts and build new knowledge and capabilities.

Workers who exhibit all three attributes have what we have defined as the passion of the Explorer. Because of their potential for dramatic impact in their organizations, management needs to get better at recognizing and cultivating passion in the workforce to transform their businesses. Passionate workers will thrive in the right work environment, and workers with some, but not all, of the attributes are key targets for internal talent development efforts to increase this limited stock of resilient workers.

The Center for the Edge’s most recent survey (see sidebar “About the data: Survey and interviews”) revealed that 12.3 percent of the US workforce exhibits the passion of the Explorer. While this represents a 15 percent increase in passionate workers over the previous year, it is only a marginal improvement for the resilience and performance of individuals and companies. It is possible that a gradually improving labor market is allowing people to shift into work they are more passionate about, although we lack enough historical data to test this hypothesis.

Despite the modest increase, however, the survey findings show that passion is still very rare in the US workforce: 87.7 percent of workers do not have it. However, nearly 50 percent of the workforce has one or two attributes of passion. Figure 1 shows the talent archetypes, introduced in Unlocking the passion of the Explorer, of individuals who exhibit some attributes of passion. These individuals are a source of tremendous potential if organizations can better amplify the attributes of passion they have and cultivate the attributes of passion they do not have.

The low percentage of Explorers in the US workforce is not surprising. In fact, it is expected. For decades, companies have focused on developing structures and processes to maximize efficiency and predictability. In this type of environment, passion is viewed as suspicious or too risky. What if the constant experimentation of a questing worker results in a process failure? What happens if a connecting worker accidently shares a company secret? How can leaders convince a worker who wants to impact a domain that these opportunities exist within the company? These are valid concerns. However, the benefits associated with passion, and the downside of not realizing those benefits, increasingly outweigh the percieved risks.

Importantly, workers who have the passion of the Explorer differ from nonpassionate workers in some interesting ways. Explorers are 50 percent more likely to report being rated as “meeting or exceeding expectations according to their most recent performance evaluation” than people with no attributes of passion.7 Explorers, on average, also work five hours more per week than workers who are not Explorers and are 18 percent more likely to claim around-the-clock availability than those with no attributes of passion. Explorers are also more likely to switch jobs frequently (an Explorer is 18 percent more likely to report switching jobs frequently in their careers than workers with no attributes of passion). Interestingly, however, 45 percent of Explorers report that they are in their dream jobs at their dream companies.

What is at the heart of this last apparent contradiction? Part of the answer lies in the expectations that passionate workers have about their work. By definition, passionate workers are drawn to new challenges and will seek them elsewhere if they are not finding them within the confines of a job or organization. Note, too, that especially in large organizations, “job” is not necessarily synonymous with “work” or “company.” Some respondents reported being in their dream job but not at their dream company, while others said that they were at their dream company but not in their dream job. A lucky few reported having both. Similarly, respondents who report frequent job changes may either be pursuing more challenging roles within the same company or switching companies.

In the right environment, the Explorer’s attraction to difficult challenges, combined with the desire to make an impact, can make Explorers more likely to achieve ever-higher performance. Explorers fundamentally thrive on challenges and derive energy from environments that allow them to constantly quest and learn. As a result, workers with the passion of the Explorer are at a lower risk of burning out from working hard, as long as they are in an environment that supports their desire to quest. Managers should realize that Explorers run a greater risk of being “snuffed out” by a work environment that discourages or penalizes behaviors aimed at growth and connecting. For these workers, presenting engaging challenges will be more effective motivation than simply demanding more work in exchange for extrinsic rewards.

The tactics companies sometimes use to improve overall performance may be counterproductive or frustrating for Explorers. For example, high performers are sometimes placed in narrowly scoped roles in the hope of using their expertise to improve productivity in a specific area. This strategy may also be perceived as political, as it tends to keep everyone in their organizational lanes. An Explorer’s desire for new challenges and desire to connect with others, irrespective of boundaries, leads him or her to perceive such a situation as confining and can lead to deep dissatisfaction for a passionate worker.

As with most of our other interview subjects, KimChi Tyler Chen, communications manager at Intuit, describes herself as “restless” and always looking for something new to learn and challenge herself. She credits Intuit with being explicit about supporting its employees in seeking out new challenges within the company through an opt-in program of “rotations.” In addition, as part of their biweekly one-on-one meetings, her own manager always asks her, “How are you doing, KimChi? What would you like to be learning or doing next?”8 Supporting and rewarding those with questing and connecting dispositions can be the difference between retaining and losing a high-potential worker.

It is also important to understand that high-potential workers at risk of leaving a firm may number more than a mere handful of individuals. Overall, around half of all Explorers report being in their dream job but would rather be at a different firm, or not being in their dream job but happy at their company. While this at-risk group represents only 6 percent of the total population, it represents half of the passionate worker population. Similarly, 54 percent of high-potential workers, who have two out of three of the attributes of the Explorer, are at risk of leaving their firms.

Passion vs. ambition

What is the difference between a passionate worker and an ambitious one? Is one better than the other? Both often work extra hours and are performance-oriented. Both have the potential to drive significant performance improvement in the organization. However, while ambition and drive are sufficient in a world that is predictable, it is not enough in a world of constant change and disruption.

Ambitious workers tend to be motivated by external rewards and recognition (see figure 2). They figure out the performance metrics needed to achieve the next level or reward and work toward those metrics. Often, they focus more on the metric itself or on enhancing a resume in order to get to the next opportunity than on the actual work. Because of this orientation toward maintaining the status quo, ambitious workers are less likely to challenge an organization’s goals, practices, and policies; as a result, they are less likely to identify new possibilities for how things might be done or to see new opportunities for the organization in response to emerging trends or disruptions.

Passionate workers, on the other hand, are internally motivated through their desire to quest, connect, and make an impact. They focus on their own learning and achieving more of their potential rather than on preset metrics or external rewards. As a result, passionate workers often challenge conventions and offer new perspectives, and they are more likely to be able to step back and reframe the organization’s approach to a specific task or to the entire market. They take on new challenges that may not advance (or may even be detrimental to) their careers, and as a result, pull their teams along with them to new levels of performance and to attempt promising, though possibly risky, ventures.

In the world of the Big Shift, where the need for continual change is becoming more apparent, passionate workers are the ones who can help companies build resilience and navigate the world of constant disruption.

Who is the Explorer?

What does an Explorer not look like (on the outside)?

Is the typical Explorer a 28-year-old PhD whiz at a start-up, a creative genius in an ad agency, or a midlevel professional at a Fortune 500 firm? Almost everyone has some preconceived notion of what a person who is passionate about his or her work looks like. Many of these stereotypes about passion, however, are incorrect.

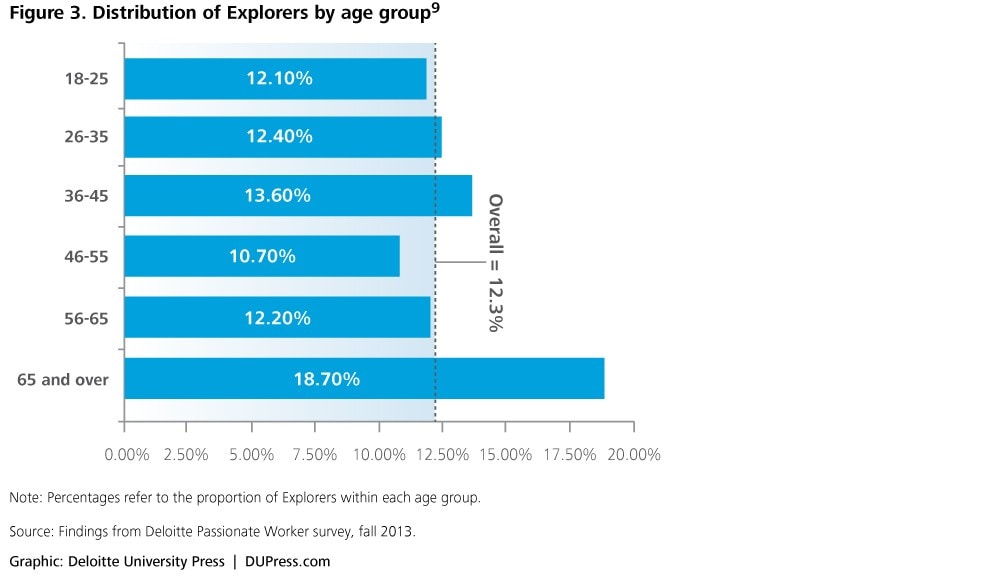

Myth 1: Age matters. One common preconception is that passion for work springs from youth. Alternatively, some believe that passion for work can only come with age, as one gains experience and spends time developing expertise in a job. Our data directly contradict both views. Analysis shows that age does not have a statistically significant impact on worker passion. Workers exhibiting the attributes of the passion of the Explorer can be found at all ages. There is no significant difference between the average age of the Explorers (48.72 years) and the rest of the workforce (48.49 years), nor are Explorers disproportionately concentrated in any age group (see figure 3).

See endnote 9

See endnote 9

Why doesn’t age matter? It may be because different individuals follow multiple paths to developing the passion of the Explorer. For some, an early desire to make an impact in an industry is so strong that it compels the development of the other two attributes. For 24-year-old Fatema Waliji, an SEO specialist at TripAdvisor, discovering her passion came relatively easily. She knew, based on her experience growing up in Tanzania, that she wanted to make an impact through a company that positively affected the developing world. When she “stumbled” upon an opportunity for an internship at TripAdvisor, she quickly realized the impact that technology could have on the developing world and was able to see how her work at TripAdvisor could develop needed skills and further her learning to help her achieve that long-term impact.10 For others who become Explorers early, the questing disposition is so inherently strong that it overcomes other obstacles, including less-than-supportive work environments, and leads them to discover a domain to commit to relatively early. Christopher Strieter, the winemaker, already exhibited strong questing and connecting dispositions in college. His deep exposure to the wine industry was serendipitous.

For some, passion does come with experience. But others whose careers have taken them through work environments that squelched passion may discover the passion of the Explorer only when they enter a new work situation where questing and connecting are encouraged. Geoffrey West, distinguished professor and past president of the Santa Fe Institute, didn’t find his passion in academia as he’d originally expected. In fact, his experience as faculty with some vaunted academic institutions left him disillusioned by the environment. Surprisingly, when he took a job at “a huge government organization that is the last place you’d expect passion,” the particular group he helped to found and the role he played allowed him to experience the collegial, learning-focused scholarly environment he’d been seeking. Later, at the Santa Fe Institute, he discovered a passion for community leadership when he was asked to act as the institution’s interim president, despite “never, ever aspiring to that type of leadership or administrative role.” Along the way, this theoretical physicist also discovered that his passion was leading him into the field of biology and urban studies.11

Mentors and the right type of leadership and management play a role in sparking passion. These individuals can act both as catalysts, by sharing their own passion for the industry and work, and as models, by actually demonstrating the skills and tactics for effectively connecting or for using organizational structures to open new avenues for questing. Serendipity can also be a factor in how early or late an individual discovers the domain on which he or she wants to make an impact.

The finding that passion is age-agnostic has immediate implications for businesses looking to revitalize their workforces. First, bringing in young talent is no guarantee that the new workforce will be fundamentally more passionate, and by extension more innovative or better able to improve performance, than the existing workforce. Similarly, businesses should look to older workers not only for their experience but also for their potential passion, which older workers are as likely to have as younger workers. Businesses should pay attention to encouraging the attributes of the Explorer in professionals of all ages, as well as in apprentices and trainees, in order to deliberately cultivate worker passion and to help the workforce develop new skill sets and expertise.

Myth 2: Firm size matters. In the era of the overnight start-up, we tend to think that passionate workers would be concentrated in smaller firms. After all, these firms can provide freedom from rigid organizational structures and job descriptions; in fact, they often require employees to wear multiple hats and help solve an array of challenging problems that vary by the week—exactly what an Explorer might be looking for to accelerate his or her own learning. Our latest data do not support this preconception, however. We found that large firms are just as effective, or ineffective, at cultivating passion in the workforce as smaller firms. Specifically, 12.52 percent of the survey respondents at smaller firms (those with fewer than 1,000 employees) were Explorers, while 12.16 percent of the respondents at large firms (those with more than 1,000 employees) were Explorers.

Of course, the survey data cannot reveal the story behind the somewhat narrower passion gap between large and small firms compared to last year. What is clear is that smaller firms cannot assume that their size alone will make them better able to attract and retain Explorers. Conversely, large firms should not give up on competing for and cultivating talent with the attributes of the Explorer. In fact, a large firm, if it is not hampered by too many policies and restrictions that squelch passion, can often offer more opportunities for learning and challenge precisely because of its size. However, there must be an intentional effort not to let the seemingly inevitable inertia of a large organization stand in the way of supporting questing and connecting. Rather than size of firm, what matters is whether a person has opportunities to quest and learn. In Strieter’s case, he took a variety of jobs within the wine industry to learn and be exposed to each aspect of the business; he left each job when he was no longer learning, irrespective of firm size. While some workers worry that, in the long term, they will run out of opportunities for questing and learning at one company, Diana Simmons, senior director of product commercialization and process and systems improvement at Clif Bar & Company, has been at the company for 10 years—“far longer than I ever expected.” Despite its size (approximately 400 US employees), the company’s growth and efforts to innovate have continued to provide her with new roles and new opportunities that negate the need to look elsewhere.12

Myth 3: Only certain groups of people can have passion. Are the attributes of worker passion something that we are all universally capable of having, or is the passion of the Explorer a function of particular American industries or regions? With regard to geography, our data show that a worker’s place of residence does not influence his or her likelihood of being passionate, at least not within the United States. So, while factors such as the presence of skilled labor will continue to be important in site selection, companies should expect to be able to find and cultivate Explorers regardless of the particular region of the country where they are doing business.

While it is conceivable that some industries might be more amenable to fostering worker passion than others, the data on industry is inconclusive. Again, there is the problem of how survey respondents understand and interpret industry designations and whether they identify as working within a specific industry. Both in the survey results and our interviews, we found passion and attributes of passion across a wide variety of sectors and types of work. We did find passion in software start-ups, but we also saw it in traditional enterprises. Consider Mandar Apte, a chemical engineer who won the Ashoka League of Intrapreneur award for creating an innovation learning program based on mindfulness practices while working in Shell’s GameChanger program. He has been with the company for 14 years and continues to find himself supported in taking on new challenges where he can make the most social impact.13

Myth 4: Educational attainment determines passion. Again, this seemingly plausible idea did not hold up under scrutiny. Despite Explorers having a slightly higher educational attainment at the postgraduate level (28 percent of Explorers vs. 23 percent of all workers), further analysis reveals that educational attainment overall does not have a statistically significant impact on having the passion of the Explorer. Instead, measures of internal drive and external environment are better predictors.

Myth 5: Only knowledge workers can be passionate. While Explorers are overrepresented at higher corporate levels, even some front-line workers reported being passionate (see figure 4). That said, it is true that the percentage of Explorers increases at each successive rung of the corporate ladder. One explanation could be that organizations appreciate the behaviors of Explorers and therefore reward Explorers with promotions. However, another, possibly more likely, explanation is that this distribution reflects decades of the practice of designing organizations and operations to maximize efficiency and predictability. As a result, workers, especially at the front line, are trained to follow detailed process manuals, and deviations are discouraged. In this kind of environment, even an Explorer is discouraged from questing or connecting; thus line workers are less well represented among the passionate relative to higher-level roles where there may be more degrees of freedom in questing and connecting.

In a rapidly changing world, however, front-line workers may be the ones who can sense opportunities first. For example, a call center agent is often the first to notice trends in customer requests or questions. As another example, going back a few years, the Toyota Production System was designed to tap into the insights and desire to improve performance in front-line workers. Assembly line workers were tasked with finding new ways to achieve the company’s goals in safety and product quality. One way front-line workers were given a path to make an impact was the Andon cord. If a worker noticed a potential safety or quality issue, he or she could stop the entire assembly line by pulling the cord. Further, the workers would then be involved in resolving the issue. These stoppages were celebrated and the worker’s impact acknowledged.14

On the other end of the spectrum, many managers and executives have the opportunity to impact the direction of the company and its initiatives. Their jobs require connecting with others in order to learn from industry peers and stay apprised of industry trends. They are asked to take on challenges and experiment with new solutions, and they see how their work impacts the most strategic goals of the company. As such, they are in work environments that encourage them to express the attributes of the Explorer, and they are more likely to be aware of their own potential and impact.

By creating the right work environments at all levels of the organization, companies have the potential to unleash the attributes of passion among workers at all levels—not just management—and to increase the number of Explorers within their workforce.

Debunking these preconceptions as myths suggests the need for a profound change in the way leaders try to identify the best talent within their organizations and, especially, the way they go about recruiting and hiring talent into their organizations. Firms almost always place an explicit premium on educational attainment and, less explicitly, are swayed by preconceived notions of what type of person will be most committed to their work and most valuable to the company. Granted, there is no doubt that workers with advanced degrees bring key skill sets and important theoretical backgrounds. A younger or older person may bring insights from his or her generation that are unique and valuable. But what firms need to realize is that, while these characteristics are valuable, they are not indicative of whether an individual has the passion of the Explorer or any of its attributes. For this reason, organizations seeking top talent must be more deliberate in identifying the attributes of passion among both candidates and the existing workforce, as well as in recognizing the potential for passion to multiply the value of the core skills they seek in employees. To do this, it is necessary to understand how the internal drive of passionate workers differs from that of the rest of the population.

What are Explorers actually like (on the inside)?

Explorers love their work. It is the work and the pursuit of improved performance related to their work that keeps them going. Of all of the variables tested, “loving my work” is the single best predictor of the passion of the Explorer. This indicates that Explorers tend to positively express themselves about their work, which, for many people, incorporates both the type of work they do, the role they play, and the management environment they do it in. It also suggests that a work environment that doesn’t elicit such responses may tend to discourage worker passion. Explorers’ willingness to work longer hours and be more available stems from this internal drive to learn and improve performance at work.

Beyond working harder, passionate workers also have a different tolerance for risk at work. They are intrinsically motivated to forge ahead with challenging problems and take significant risks to improve performance. Explorers are significantly more likely to take risks to improve their performance than workers with no attributes of passion: 46 percent of the Explorers in our study identified themselves as being very willing to take significant risks. Explorers’ propensity to take risks at work, such as embracing challenging tasks and taking on projects that require new skills, is three times that of workers who have no passionate dispositions.15 “Safe” jobs that lack opportunities to fail in the pursuit of building new skills, acquiring knowledge, and enhancing performance will not satisfy an Explorer. Being insulated from all risk can turn a daring Explorer into a departing Explorer. This is likely one of the reasons why Explorers switch jobs more frequently than the average Joe.

Explorers don’t just take risks; they are innovators at heart. They report innovating twice as frequently (37 percent) as nonpassionate workers do (18.5 percent).16 Explorers experiment with alternative approaches to pursue better results in whatever they do. This tendency complements the connecting disposition and leads Explorers to function as incubators of innovation. They connect with other innovators across the organization and bring them together to take on new challenges as well as some of an organization’s most intransigent problems, often at great risk of failure. With support and some direction, this aspect of worker passion can be harnessed. Indeed, it may hold the key to breaking long-established constraints and cost/benefit trade-offs that have limited firm performance.

Despite their tremendous value to the organization, Explorers are not driven by income. Our analysis found that income was not a statistically significant predictor of possessing the attributes of the Explorer.17 In fact, of the archetypes described in figure 1, only connectors are driven by income (that is, income is a significant predictor of belonging to this subgroup). In spite of not being driven by income, Explorers turn out to be overrepresented in higher-income brackets and underrepresented in lower-income brackets. One possible explanation is that, overall, the types of jobs that provide the most satisfying work environment for an Explorer also tend to pay better. Alternatively, Explorers in the right work environment may perform so well that they tend to receive higher salaries and bonuses.

This distinction between what Explorers earn vs. what motivates them is critical for management. Explorers may be paid a premium because of the value they deliver; however, giving a better raise is unlikely to increase a worker’s passion. Instead, companies need to explore other ways, beyond compensation, to deliver an enriching work environment—one where employees have sufficient autonomy to take risks, opportunities to improve their performance, and the chance to connect with others across and beyond the organization. Attention paid to creating this environment will help not only to attract and retain Explorers but also to cultivate potential Explorers and unlock their potential throughout the workforce.

Armed with a better understanding of who passionate workers really are, what practical tools can companies use to help better recruit, retain, and cultivate passion?

Explorers and social media behavior

To better understand Explorer behavior beyond personal attributes, we collected Twitter handles from respondents and tested whether Explorers had a statistically identifiable pattern of speech or selection of topics when communicating on Twitter. Additionally, we tested whether different kinds of passionate workers had more or fewer followers. Unfortunately, the rate at which respondents shared their Twitter handles was so low that neither practical nor statistical significance could be assigned to differences between the groups in any way. This is an area for future study pending improvements in sample size. We are hopeful that this new methodology of combining survey data with Twitter data will allow us to perform large-scale classification studies on the online behavior of Explorers in the future.

Cultivating passion at work

How to unlock the passion of the Explorer in your workforce

Passion either flourishes or disappears when put in certain environments. So how can companies create environments that unlock the potential of their employees? Organizations should rethink their work environments—from the physical space to virtual environments to management practices—to understand how policies, practices, and actions impact the attributes of passion.

From the analysis of our survey data, we have identified four organizational components that are most strongly correlated with a person being an Explorer. These are the organizational attributes that describe what passionate workers are likely drawn to in an organization and therefore have voluntarily opted into. At the same time, these organizational attributes illustrate work environment characteristics that are more likely to cultivate passion within workers. They are:

- Workers are encouraged to work cross-functionally (40 percent increase in likelihood to be an Explorer)19

- Workers are encouraged to work on projects they are interested in, even on those outside of their responsibilities (34 percent increase in likelihood to be an Explorer)

- Workers are encouraged to connect with others in their industry (17 percent increase in likelihood to be an Explorer)

- The company often engages with customers to innovate new product and service ideas (14 percent increase in likelihood to be an Explorer)

These four characteristics are well aligned with the attributes of passion. When workers are encouraged to work cross-functionally and connect with others in their industry, they tap into their connecting disposition. When workers are encouraged to work on projects they are interested in instead of (or as well as) those they are assigned to, they tap into their questing disposition. When workers are encouraged to engage with customers and other ecosystem partners to innovate together, they are seeing the impact they are making, helping to cultivate commitment to domain.

While these four organizational attributes turned out to be the most predictive of passion in our survey, other tactics exist that companies can deploy to unlock the attributes of passion. In our study of various work environments and their impact on performance, we identified three goals that companies should work toward when building their physical and virtual environments, as well as in designing their management practices (see figure 5). First, companies should define high-impact challenges by helping workers and teams to focus on the areas of highest business impact, learning, and sustainable improvement. Second, companies should strengthen high-impact connections by enabling workers to connect with people who matter, both inside and outside the organization. Finally, companies should amplify impact by augmenting workers’ impact with the right infrastructure. By building environments with these three goals in mind, companies can help unleash passion in their workforce.20Next, we will review some specific tactics that companies can use to unleash the attributes of passion while focusing on the three goals of effective work environment design.

Building commitment to domain

Helping individual workers understand the impact that they are having on the company’s (and even the broader business ecosystem’s) performance is a great catalyst for developing commitment to domain. Organizations should share the key challenges they are facing with all workers—from the executive suite to the front line. Workers should be given a chance to work on those challenges if they are interested, even if their job description does not call for it. For example, Geoffrey West, the theoretical physicist, knew early on that he wanted to learn more about the “basic forces of nature,” which fostered a commitment to the domain of scientific research. His interests started in the field of fundamental physics. Through his careers at Stanford University, a national lab, and the Santa Fe institute, he was able to see the impact he was making on the field of science by solving challenges and moving his chosen area forward. Eventually, pursuing a personal interest, West explored the field of biology and then embarked upon understanding complex systems at the Santa Fe Institute. Thus, while West switched organizations and roles, he was still committed to the domain of scientific research, but he wouldn’t have made the connections between his work and complex systems if he hadn’t first had latitude to dabble outside his assigned field of expertise.

Connecting performance to impact is an important and often missing element. Companies often have corporate-wide performance metrics that are irrelevant to, or misaligned with the goals of, specific units. The managers who were able to build commitment to domain were able to modify or interpret corporate metrics to make them relevant and meaningful for their teams. At Clif Bar, Diana Simmons developed a matrix of competencies and metrics that she believed were most important for her team: “We still use the company’s ‘five ingredients’ (connect, create, inspire, own it, and be yourself) framework as well. But my team is an influence-based, cross-functional product launch team—it seemed obvious that we needed a unique set of skills and leadership tools to succeed in this role.”21 Similarly, at TripAdvisor, Fatema Waliji says her group created its own performance management system to reflect the most relevant metrics and goals: “HR is fully supportive of it, and it’s easy for me to gauge my impact on my team because the metrics make sense to our work.”22

Unlocking the questing disposition

To unlock a worker’s questing disposition, companies should create experimentation platforms: environments that combine tools, processes, and management practices focused on rapidly prototyping solutions. Some companies, like Intuit, have excelled at creating these platforms. Intuit’s Design for Delight program allows teams to work directly with customers in order to address an issue through a rapid prototyping process.23

Experimentation is often associated with failures: Not all prototypes work. The way companies handle these failures has a direct impact on whether workers will experiment. Environments where failures are not an option discourage any desire to experiment, especially if a worker’s job is at stake. These are environments that value predictability and scalable efficiency and view questing as undesirable. However, Simmons found it hard to specifically define a time she failed: “Every day is a series of ‘mini-failures,’ I guess, because I’m always testing my ideas and approaches with others. I always focus on the larger goal, and as long as this goal is still correct, even if the tactics you take toward that goal do not work, that is not a failure.”24 Her remark illustrates how Clif Bar’s culture of innovation supports risk taking as long as it moves the company toward a larger goal.

Failures should be acceptable, especially if they are cheap and quick. Modular processes and products allow for experiments within each module, and even failures do not need to threaten the entire process, or product. Companies should try to redesign their processes and products to reduce risk and facilitate experimentation.

But in order to learn, experimentation is not enough. Workers should be given timely (as close to real-time as possible) and context-specific feedback. Additionally, workers should be allowed time and space for reflection and tools to capture and share lessons learned. The challenge at many companies today is how to make this process seamless. At many organizations, feedback, reflection, and capture are extra steps that workers have to take in addition to their daily activities. However, tools such as gamification platforms can integrate these processes more into daily work.

Unlocking the connecting disposition

Connections can lead to new learning. Companies should create environments—both physical and virtual—that help workers to develop new connections and also to strengthen their existing relationships. For example, companies can create environments that foster serendipitous encounters. Many firms already build their physical environments with the common areas strategically positioned to allow workers to “bump into each other.” These environments should also be developed in virtual settings. For example, cameras could be located in the common areas where remote workers can see their colleagues and interact with them. Additionally, screenshots from whiteboards in common areas could be distributed to enable a remote team to comment and add their perspectives, even if they were not part of the original serendipitous discussion.

Companies should develop platforms for collaboration with customers and other ecosystem players to share knowledge and develop solutions. A key aspect of such a collaboration platform is tools for connecting, including automatically generated reputation profiles. One example of a collaboration platform is that developed by RallyTeam, one of the start-ups that presented at the San Francisco Tech Crunch Disrupt’s Battlefield competition. The company challenged the usefulness of corporate training programs and instead suggested a way to facilitate on-the-job learning. It developed a platform that connects workers interested in learning a new skill (often outside their job description) with opportunities in need of extra resources. The results are documented, and workers receive performance badges, share project snapshots, and record additional “skills” on their online profiles. RallyTeam provides both a platform for connecting workers to opportunities and tools for creating action-based reputation profiles. The emergence of companies such as RallyTeam is evidence of the need for workers to connect and learn both inside and outside the four walls of their enterprise.

Work environments and management practices that cultivate the passionate disposition will not only help stimulate and engage workers who are already passionate but also allow those who do not demonstrate all the attributes of a passionate worker to cultivate the missing ones. Sadly, many executives focus more on attracting and retaining talented workers than on designing the right work environment, even though an environment where workers can learn fast, unlock their passion, and improve performance helps attract and retain workers. Word will spread that the company develops workers more rapidly than anyone else, and people will line up to apply. And why would anyone leave the environment where they can learn and improve performance most effectively?

When evaluating your work environment, consider the statements that the Explorers we interviewed made. How will your organization treat workers who think this way?

- I never ask for permission. I just do it.

- From one perspective, I have a series of mini-failures every day, but I don’t view that as failure.

- I get restless often.

- I want my work to make an impact on something important to society.

- I like to know that what I’m doing matters to the company.

- I don’t want to do anything that I can’t learn from.

- I have a goal, and I’ll stay as long as my management supports me in getting the experiences I need to move closer to that goal.

Recruiting Explorers

While developing the right work environment should be a priority, it is hard to ignore recruiting. Current recruiting practices at many companies are too rigid and often focus on analyzing a candidate’s credentials, overlooking his or her potential. Instead, companies should understand how candidates have demonstrated commitment to domain, questing, and connecting attributes in either their previous jobs or outside their career. Evidence such as participation in online communities (for example, GitHub) and contributing to forums can show that the candidate is truly passionate about the field.

Additionally, both organizations and workers should seek to be aligned in terms of values or personal aspirations. For example, early in his career, Dave Hoover faced a choice: Join a well-established financial institution’s technology group or a two-person start-up. At the time, he had three young kids and a mortgage, so the safety of the established organization seemed attractive and, in fact, would have provided an opportunity for advancement within the IT field. However, Hoover was also passionate about blogging and being a thought leader in the area of learning. He realized that his interest in blogging and speaking at conferences would help further the business goals and mission of the small start-up, while at the financial institution it would, at best, be tolerated but might also be viewed as a liability and prohibited. “I really enjoyed sharing ideas,” says Hoover. “So the right choice was clear for me. I wanted the organization that my passion best aligned with.” Hoover’s gamble paid off, and he has enjoyed a successful career as a cofounder of the start-up Obtiva, which was later acquired by Groupon. Hoover went on to cofound Dev Bootcamp, a short-term immersive “boot camp” program that transforms novices into web developers; this operation was recently acquired by Kaplan.25

Similarly, Clif Bar’s Simmons has spent her career looking for work environments that aligned with her desire to impact the environment and improve sustainability. Over time, she realized that she also needed work that took advantage of her particular skills and strengths. At Clif Bar, a company committed to sustainability where she led a number of successful product launches and worked to make the corporate sustainability initiative part of every product, she found alignment between the company’s goals, her skills, and her values. When the work environment and personal values and goals are aligned, workers are more likely to demonstrate the attributes of the passionate and make an impact on both the company and the broader ecosystem.

In the appendix, “Suggested behavioral questions for recruiting Explorers,” we provide some situational questions that recruiting teams can use to identify the passionate.

Retaining Explorers

Designing the right work environment helps retain Explorers. After all, if they do not learn and improve their performance quickly, they will look for another environment where these objectives can be satisfied. Additionally, as we discussed earlier, retaining Explorers with financial incentives is not sustainable because this tactic does not effectively impact Explore retention. Employers could use talent surveys to assess whether they are cultivating the passionate and to determine the impact of work environment initiatives.

We built a predictive model to help identify measurable characteristics that can best predict whether or not someone will be passionate. Listed in descending order, these are the top 10 predictors of whether a person is a passionate worker. These indicators could be used by companies in their worker surveys to understand the state of passion within the organization:

- To what extent do you love your work?

- In my job I’m encouraged to work on projects I am interested in, outside of my direct responsibilities.

- In my job I’m encouraged to work cross-functionally.

- I try to incorporate outside perspectives into my work.

- I talk to my friends about what I like about my work.

- I usually find myself working extra hours, even though I don’t have to.

- In my most recent performance evaluations, I was rated as meeting or exceeding expectations.

- I choose to be available to work 24/7, sometimes even on vacations.

- My company provides opportunities to connect with others in my industry.

- My company often engages with customers to innovate new product/service ideas.

Used in corporate talent surveys, questions that assess these factors can help leaders assess the health of a firm’s workforce and, in conjunction with a firm definition of worker passion, point to a set of levers that can help improve morale among passionate workers. Additionally, companies can cross-reference this talent survey data against performance evaluations to see if Explorers are getting the recognition they deserve. This could help companies fine-tune the performance evaluation process. Finally, the organization could engage the passionate workers identified through the talent survey to help redesign the work environment to cultivate passionate attributes in other workers.

One of the keys to retaining passionate workers is to make sure they do not feel alone. Connecting them with other passionate workers and allowing teams of Explorers to work together on challenges, coupled with a motivating recognition system, can help these workers feel energized.

The bottom line

In this report, we have made a number of recommendations on how firms can cultivate, attract, and retain Explorers while simultaneously advocating a new view of passion within the workforce. In aggregate, this challenge could seem overwhelming. However, at their core, our recommendations boil down to the following three principles:

1) Look for where your preconceived notions about the profile of a passionate worker are stopping you from identifying talent both externally and internally. Passionate workers come from all age groups, educational levels, and backgrounds.

2) Recognize that passionate workers outearn and outperform their peers because of their internal drive for sustained learning and performance improvement. Take risks to cultivate these dispositions, and passionate workers will take risks for you in return.

3) Cultivation of passionate workers internally is probably the most effective way to increase the proportion of passionate workers in your organization. Organizations should evaluate their work environments to understand where they cultivate or discourage passion. The right work environments will help attract, retain, and develop Explorers.

Appendix: Suggested behavioral questions for recruiting Explorers

Below are some questions interviewers could use to test worker passion. These are just suggestions. Each company should reflect on what the various attributes of passion mean for its work environment and develop its own approach to testing for attributes of worker passion.

Commitment to domain:

What is the market, area, industry, or function that you want to impact in 5–10 years?

What does success look like?

How can this job or position help you achieve the desired impact?

Individuals with commitment to domain will have an area that they want to impact professionally. For example, a person may want to build online learning communities or change the way diabetes education is conducted. To test further for commitment to domain, an interviewer can ask what the candidate has done to date in this area. A person with true commitment to domain will often already have taken steps in this area and see your job or position as a way to accelerate his or her efforts.

What roles have you taken on in your career to date?

How did these roles and experiences move you closer to achieving your goals?

Individuals committed to a domain often interpret their experiences both within and outside the domain as meaningful to achieving their goals. For example, a candidate who wants to make a difference in the developing world will likely view his or her experience at a technology start-up as a stepping stone. He or she may view the skills and learnings from managing uncertainty and understanding technology trends as important skills for helping communities in emerging economies develop.

Questing:

When faced with a new project or challenge, what is your first thought?

Look for candidates who view new challenges as opportunities to learn new skills and improve performance. Workers with a questing disposition will often welcome new challenges with excitement and anticipation instead of fear and concern.

Describe a situation where you failed. How did you adjust? What did you learn?

An individual with a questing disposition will often view failures as necessary steps to achieving a goal. Failures, they think, are a necessary part of experimentation. Moreover, passionate workers may not even see these as failures but as the steps that get them closer to making an impact. “I have many small failures every day,” stated an Explorer we interviewed.

Connecting:

Describe your approach to understanding a topic of which you had no prior experience.

As a part of his or her approach, an individual with a connecting disposition will reach out to others—for example, communities and teams inside and outside the organization—to learn about a new area. For example, an individual may attend a meeting on a topic in digital health to meet others interested in the topic and tap into their knowledge. He or she may also join a discussion board where individuals share ideas. Finally, picking up a phone and calling a professor who is conducting research in the area is not a challenge for a person with a connecting disposition.

Describe a time when you helped someone solve a challenge.

An individual with a connecting disposition will have broad networks he or she can leverage to learn together and share best practices. Look for networks that are outside of the team or even the organization that an individual belongs to. The key is to find those who are proactive about building broad trust-based networks that help them learn and improve performance.

Bonus question:

Describe the last time you took on a challenge you were not sure you could successfully complete. What did you do? What did you learn?

This question could help test several dispositions at once. A passionate worker will first be excited by an unexpected challenge: “When I was asked to develop a new process, I was excited. This is an opportunity to learn a new skill and to make an impact!” Additionally, a passionate worker will tap into his or her networks inside and outside the company to get up to speed on the topic and share learnings and insights. A passionate worker will likely experiment rapidly, ask for real-time feedback, and reflect on the lessons learned. She or he will not be afraid to take a step back and reframe the issue or the underlying assumptions as needed. And most likely, his or her solution will be unexpected and extensive.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.