Looking for convergence: How is the government workforce similar to the private sector? has been saved

Looking for convergence: How is the government workforce similar to the private sector? Behind the Numbers, April 2017

26 April 2017

Government and the private sector can differ in their priorities. There are, however, areas of convergence where government can adopt learnings from the private sector. An analysis of both workforces helps us identify two such areas.

Introduction

Discussions about improving government often lead to comparisons with the private sector.1 Such comparisons, especially using measures of efficiency and technology adoption, sometimes appear to favor the private sector.2 Priorities can differ, however, between government and the private sector. And many government workers are in different occupations than workers in the private sector. So, what are the areas where government can learn from the private sector to be more efficient and tech-savvy?

Our analysis of the Occupational Employment Statistics (OES) data on who is working in what jobs and in which sectors shows that while there are key differences between workforces in government and business, there are areas of strong similarity as well (see sidebar “Education looms large, but is not reflected in OES government data”). Occupations such as office and administrative support, for example, make up large shares of both government and private sector workforces. In areas such as technology, the focus of both government and the private sector is changing—although in varying degrees. These points of convergence could be prime opportunity areas where government may consider emulating private sector practices.

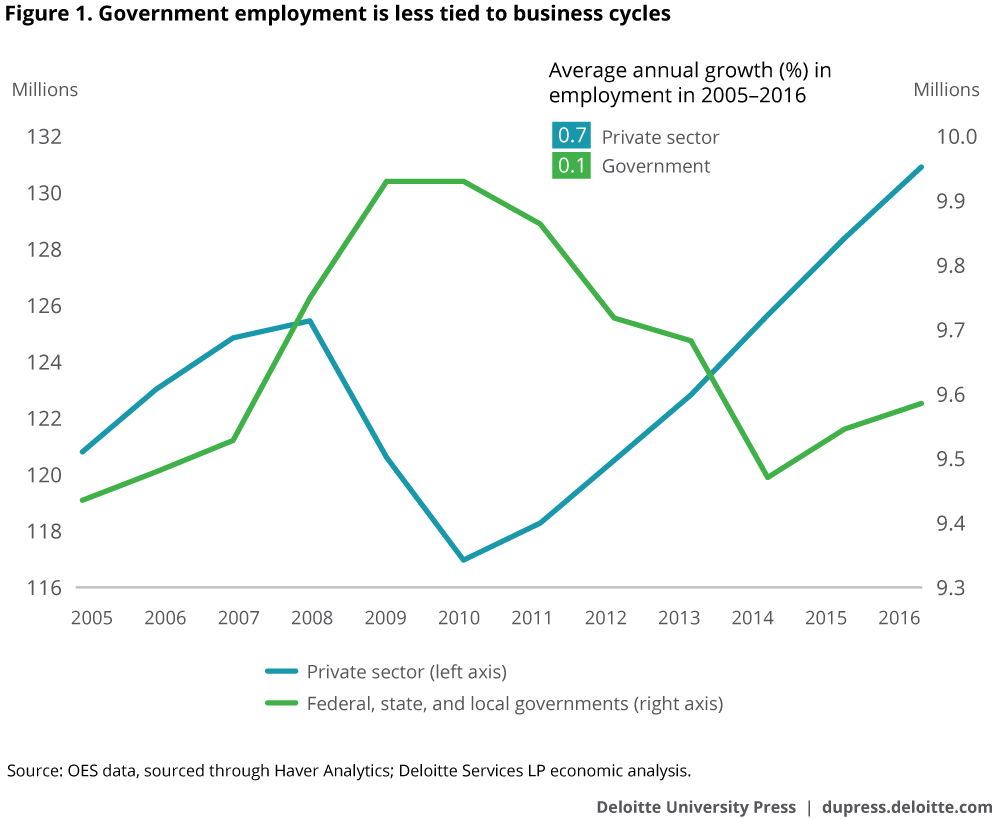

Growth rate and business cycle timing of government employment differs from the private sector

Overall, government employment has displayed a different growth pattern from private sector employment since at least 2005.3 Private sector employment grew during this period, but experienced sharp drops during and in the immediate aftermath of the Great Recession, before recovering steadily. In contrast, government employment was much slower to respond to the downturn of 2008–2009 (figure 1).4 Traditionally, government employment does not respond as much to business cycles. In this case, government employment continued to grow through most of 2009, not beginning to drop until 2010 as the ripple effects of the recession began to be felt in state and local governments.5

Different priorities can mean varying prominence of key occupations

The government workforce can differ also in composition from the private sector. Certain classes of occupation are much more prominent in government than in business, while others show the opposite pattern. Protective services, for example, accounted for 19.9 percent of the government workforce in 2016 compared to a mere 1.1 percent share in the private sector workforce. Production and sales occupations, by contrast, have a much lower share in the government workforce than the private sector (figure 2). This is again commonly a reflection of different priorities—the government has less need of sales occupations and engages in only very modest amounts of goods production.

Other differences, however, can be less easy to explain. For example, the higher share of business and financial operations in the government workforce (10.6 percent in 2016) than the private sector (4.8 percent) may initially appear unclear. However, there is often a difference in the types of business and financial operations jobs found in the public sector. Business operations; management analysts; claims adjusters, examiners, and investigators; and budget analysts all have a higher share in the government workforce than in the private sector. This may be due to more extensive oversight and control in government than in the private sector. In contrast, the private sector has a much larger share in occupations such as personal financial advisors; financial analysts; credit analysts; loan officers; insurance underwriters; and tax preparers. This is likely not surprising given that banking and insurance are almost exclusively carried out in the private sector.6

Education looms large, but is not reflected in OES government data

The Bureau of Labor Statistics provides several measures of employment. The measure we are using here comes from the OES survey. We base our discussion on OES data because it is designed to help understand the occupational structure of the US economy. However, the OES data place educational occupations separately from those associated with federal, state, and local government.

In fact, more than half of state and local government workers in the United States work in educational establishments. That’s according to another measure of employment, the Current Employment Survey (CES)—sometimes known as the “payroll” survey.7 According to payroll data, total employment in education for state government was 2.4 million and 7.9 million for local government in 2016 (figure 3). Since most government employment in the United States is at the state and local level, government education payrolls amount to almost half of total US government employment.

Since government is the largest (by far) employer of workers in educational occupations, comparisons for these occupations between government and the private sector could be misleading. By removing this component, the OES data makes the workforce in the private sector more comparable to government workforce for our analysis.

Office and administrative support occupations are comparable across public and private sectors

A function where government and the private sector show similar shares and trends in workforce is office and administrative support. In 2016, for example, office and administrative support had a 16.9 percent share in government employment and a 15.6 percent share of the private sector workforce (figure 2). However, despite this high share, the prominence of office and administrative support occupations has been declining over the years in both workforces (figure 4). A likely reason for this is the advent of technology, which has reduced some of the office and administrative-related workload. This is likely not difficult to comprehend—just look at the changes in office-related occupations over the years due to emails, word processing, statistical packages, and design software. Automation will likely only add to this trend in future.

What figure 4 also tells us is that over 2005–2016, employment in office and administrative-related occupations has fallen at a faster pace in government—at an average annual rate of 1.0 percent compared with a 0.3 percent decline in the private sector during that period. We suspect the explanation for this is that government has been slower off the blocks in introducing technology in different functions and therefore may be trying to catch up with the private sector. Likely as a result of this and a higher base to start with, the decline in the office and administrative support workforce has been faster for the government.

Technology is the second area where government can emulate private sector practices

As technology and process improvements have helped contribute to lower need for administrative personnel, there has been complementary growth in demand for information technology workers. While the share of tech workers is still low in both sectors, it is rising (figure 5). In government, the share of computer and mathematical science occupations in the workforce grew from 2.2 percent to 2.6 percent between 2005 and 2016. During the same period, the occupation’s share in private sector employment grew from 2.3 percent to 3.0 percent. These numbers show that tech jobs are growing faster in the private sector—at an average annual rate of 3.3 percent during 2005–2016 compared to only 1.9 percent in government over the same period. However, these numbers do not include contractors, who may be a larger part of the tech workforce in government.

Trends in median wages also help support the notion that government lags somewhat behind in the race for tech-related talent. In 2005, the median wage for computer and mathematical occupations was the third-highest among all occupations within government; by 2016, that had fallen to fourth place. Growth in median wages has been much slower within government for computer and mathematical science occupations compared to other occupations (figure 6)—which is surprising given that many governments have IT employee exemptions from salary restrictions. Figure 6 also shows us that the median wage in the occupation has grown at a slightly slower pace for government, on average, than for the whole economy. This is in contrast to some of the other occupations in government, shown in the figure, where wages have increased faster.

Government can start by focusing on back-office and technology occupations

Although there are differences in what government and private sector employees do, both have a substantial number of employees in administrative and tech jobs. Those are the areas in which government will be most likely to adopt best practices from the private sector. Also, as technology rises in prominence and the fortunes of administrative support occupations decline, it would likely serve government well to prepare more for a future where the share of artificial intelligence (AI) in the economy is expected to increase. Early planning and implementation within government may help pave the way for requisite education, employment, re-skilling, and wage policies essential to deal with an increasingly AI-driven future.

Workforce analytics can help refine our understanding of those organizational components where private sector ideas will be most beneficial to government efficiency. Please see our companion pieces AI-augmented government: Using cognitive technologies to redesign public sector work and How much time and money can AI save government?: Cognitive technologies could free up hundreds of millions of public sector worker hours for a deeper look at how technology is transforming government work.