Toeing the line: Improving security behavior in the information age has been saved

Toeing the line: Improving security behavior in the information age

29 January 2016

Joe Mariani United States

Joe Mariani United States Kwasi Mitchell United States

Kwasi Mitchell United States Mike Gelles United States

Mike Gelles United States Christine Elliott United States

Christine Elliott United States

Security needs to be viewed through a wider lens. Beyond technology investments, security begins and ends with people: their behaviors, motivations, and habits. Learn tangible ways leaders can link culture to strategies to actions to safeguard their organizations—and build stronger cultures.

Overview

In the floating, wooden world of the 18th century British Royal Navy, discipline and adherence to rules kept the ships above water and away from enemies. To ensure discipline, every morning the ship’s officers would inspect the crew by lining up the sailors along one of the seams in the wooden deck. With a shrill whistle signaling the start of the inspection, the sailors scrambled to put their feet on the right seam, to shouts of, “Toe the line, there!”1

While the dangers of the modern world are different, they are no less real for organizations relying on information. Even the threat of piracy is not diminished, with modern versions wielding laptops instead of cannons. Just like in the Royal Navy, the discipline of employees can help keep these information enemies at bay. But in a modern world full of distractions and ever-more technically complex threats, how can an organization ensure that its employees “toe the line” and adhere to security policies? Neither employees nor sailors are automatons, nor should they be. They are individuals with rich and complex lives. Improving security behaviors, therefore, depends upon understanding individuals and how they work together.

While the dangers of the modern world are different, they are no less real for organizations relying on information. Even the threat of piracy is not diminished, with modern versions wielding laptops instead of cannons. Just like in the Royal Navy, the discipline of employees can help keep these information enemies at bay. But in a modern world full of distractions and ever-more technically complex threats, how can an organization ensure that its employees “toe the line” and adhere to security policies? Neither employees nor sailors are automatons, nor should they be. They are individuals with rich and complex lives. Improving security behaviors, therefore, depends upon understanding individuals and how they work together.

Like a ship, an organization requires its employees and tools to be working in concert toward a common goal. By far, the most common tools used in business today are computers and computer networks. To defend the valuable information on these networks, organizations create layers of hardware protections and software code that protect data and network integrity. But what about the users of those systems? A lapse by a single individual, whether by malicious intent or by accident, can expose sensitive data and have far-reaching consequences. While high-profile leaks of national security data may be top of mind when we think of employees and security, simple errors can be just as damaging. Using a public Wi-Fi signal against policy, for instance, can compromise critical systems and cause the organization to lose valuable financial or research and development data from a hacker’s malicious attack. Such examples also highlight the close relationship between physical and cybersecurity in today’s connected world. Physical security issues such as lost identity cards or carelessly discarded bank information can compromise networks and lead to identity theft.2 Similarly, with the rise of the Internet of Things connecting physical objects to computer networks, cyber-vulnerabilities are becoming threats to physical security. As reported in Wired in July 2015, hackers can now take control of key functions of a car wirelessly, even its steering wheel, throttle, and brakes.3

Security must be designed with users in mind: individuals, with unique motivations, emotions, and cognitions.

Physical and logical security are linked as never before, and both depend on human judgment and action. Everyone in an organization must constantly be working together to comply with security policy. And unfortunately, the field of behavioral economics demonstrates to us that people—who increasingly work in complex, fast-paced environments—often make poor choices, despite their best efforts to do otherwise. Security must be designed with users in mind: individuals, with unique motivations, emotions, and cognitions. This article will examine the drivers for how individuals make security decisions, from their personality traits, to motivations and incentives, to social context. We will see how of these, the social context plays a large and often overlooked role in governing decision making. For most of us, that social context is made up of the friends, co-workers, meetings, and daily interactions of work—in short, the organizational culture of our companies. Therefore, creating a unified organizational culture with norms of behavior that reinforce security standards for each user is key to creating a secure and effective organization. Finally, using real-world examples, we will illustrate what leaders can do to develop a more secure, and even more productive, organization.

A Deloitte series on behavioral economics and management

Behavioral economics is the examination of how psychological, social, and emotional factors often conflict with and override economic incentives when individuals or groups make decisions. This article is part of a series that examines the influence and consequences of behavioral principles on the choices people make related to their work. Collectively, these articles, interviews, and reports illustrate how understanding biases and cognitive limitations is a first step to developing countermeasures that limit their impact on an organization. For more information visit http://dupress.com/collection/behavioral-insights/.

Security: A chain of individual decisions

We often think of security as an object. Like a dead-bolted door, it is what protects us and keeps us safe. However, in today’s digital age, where access to sensitive systems can come from anyone’s laptop or phone, this analogy no longer applies. Security in the digital age is not a monolithic object, but the sum of many individual decisions. If the users make those decisions correctly, along with well-built network infrastructure, they form a strong chain that can help protect sensitive data, applications, and even physical spaces. If, however, users do not follow policies and routinely take shortcuts, the chain has that many weak links in it, increasing the risk of compromise, theft, or crime.

So if security relies upon the actions of every user, how can it be improved? One natural instinct is to just “buy more security” by adding tools and features to the lines of defense. However, as we repeatedly see in security breaches reports, all the tools in the world will not protect a network or facility if users do not employ them properly. So how can an organization encourage users to make the right decisions for security every time? To begin to answer that question, we need to first understand how people make decisions.

We often think of security as an object. Like a dead-bolted door, it is what protects us and keeps us safe. However, in today’s digital age, where access to sensitive systems can come from anyone’s laptop or phone, this analogy no longer applies.

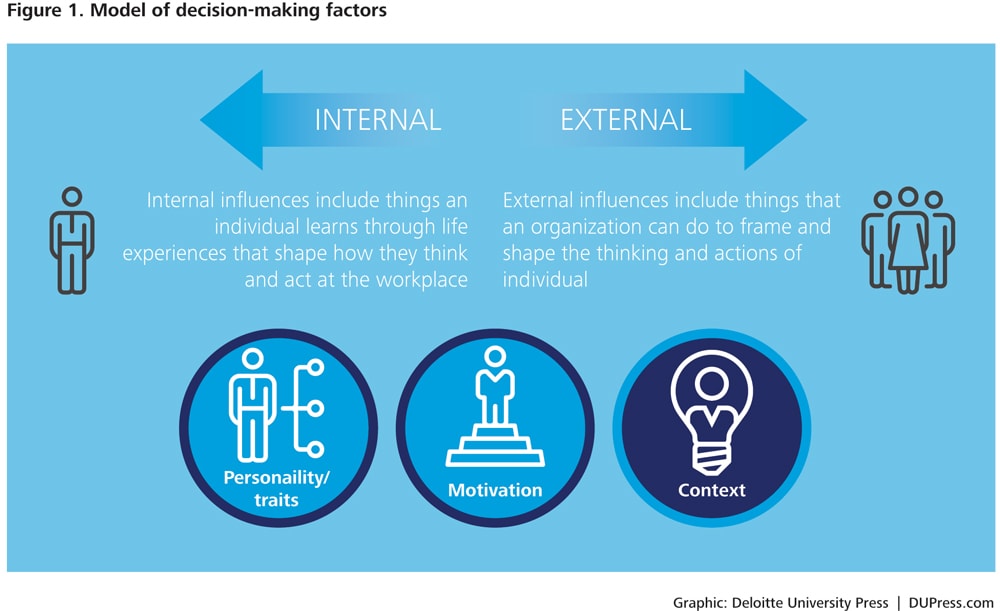

There are a number of internal and external factors that affect an employee’s decision making as it relates to policy compliance. Even seemingly unrelated factors, such as hunger or the presence of other people, have been shown to have an effect.4 Consider the simplest model of decision making, inherent in the phrase: “Every individual acts in the world.” If we wish to influence the outcome of the action—as we certainly do if we want to improve security behaviors—then we are left with three variables: (1) the individual; (2) the action and its alternative(s); or (3) the world. Therefore, if we want to understand why someone acted as he or she did, we can look at: (1) his or her personality/traits; (2) the motivation behind that action; or (3) the context of the world that influenced his or her decisions and actions (see figure 1).

Influencing to improve

Personality traits: Is it possible to hire only trustworthy people?

When thinking about how to use the three factors above to ensure that people comply with security policies, perhaps the most immediate solution is to pick the right people; examine personality traits and choose the candidates most likely to follow the policies. This is, at least in part, a strategy the US government employs with security clearances and background checks.5 By looking into your background, the government is gathering information about past behavior to assess your judgment, reliability, and future behavior if granted access to classified information, since past behavior is typically the best predictor of future behavior.6 Similarly, potential employers can analyze past patterns of behavior to determine a candidate’s judgment and reliability and provide some insight into the amount of risk their behavior would add if hired as an employee.

While this method can help identify individuals who may be at high risk for violating the rules, i.e., those with consistently poor track records of decision making, unfortunately, the process does not work in reverse. You cannot identify someone who will always follow the rules simply by looking at past decision making.

First, what qualifies as poor decision making may change over time, and these checks or clearances offer only a snapshot. For example, in the past, receiving counseling for mental health or behavioral issues was often viewed as a sign that an individual was unstable or had impaired judgment, increasing his or her risk to the organization. Today, social perceptions have begun to change. There is wider recognition that psychological treatment can effectively address issues such as grief, relationship challenges, and PTSD. Now, rather than being viewed as a risk, voluntarily seeking help for a personal issue is typically viewed as a positive sign, an example of good judgment, reinforcing trustworthiness.7

Second, even the most intrinsically trustworthy individual is still subject to the demands of context when making decisions. What would happen if a model employee were confronted with a crisis? Imagine this employee works at a health insurance company, she always arrives early to work, follows security and other policies, and consistently makes good choices. Now suppose the context of her judgments changes: her family is kidnapped and will not be returned unless a customer’s claim is approved. Here, factors external to this employee’s personality traits would play into her decisions to follow or break security policies.

In this extreme example, the employee could easily be influenced by an actual or perceived crisis that could change how she evaluated the choice, “Do I obey the policy or not?” While this employee may still value compliance to policies, the external event of the kidnapping has dramatically increased the probability that she will break the policy as a perceived solution to the crisis. While everyday events will probably not alter the valuation of alternatives as drastically as that, factors such as peer pressure and even fatigue can have a measurable impact on whether individuals follow policy. In other words, the environments that we live in, both social and physical, strongly influence how decisions are made—including those related to security.8

What is culture, anyway?

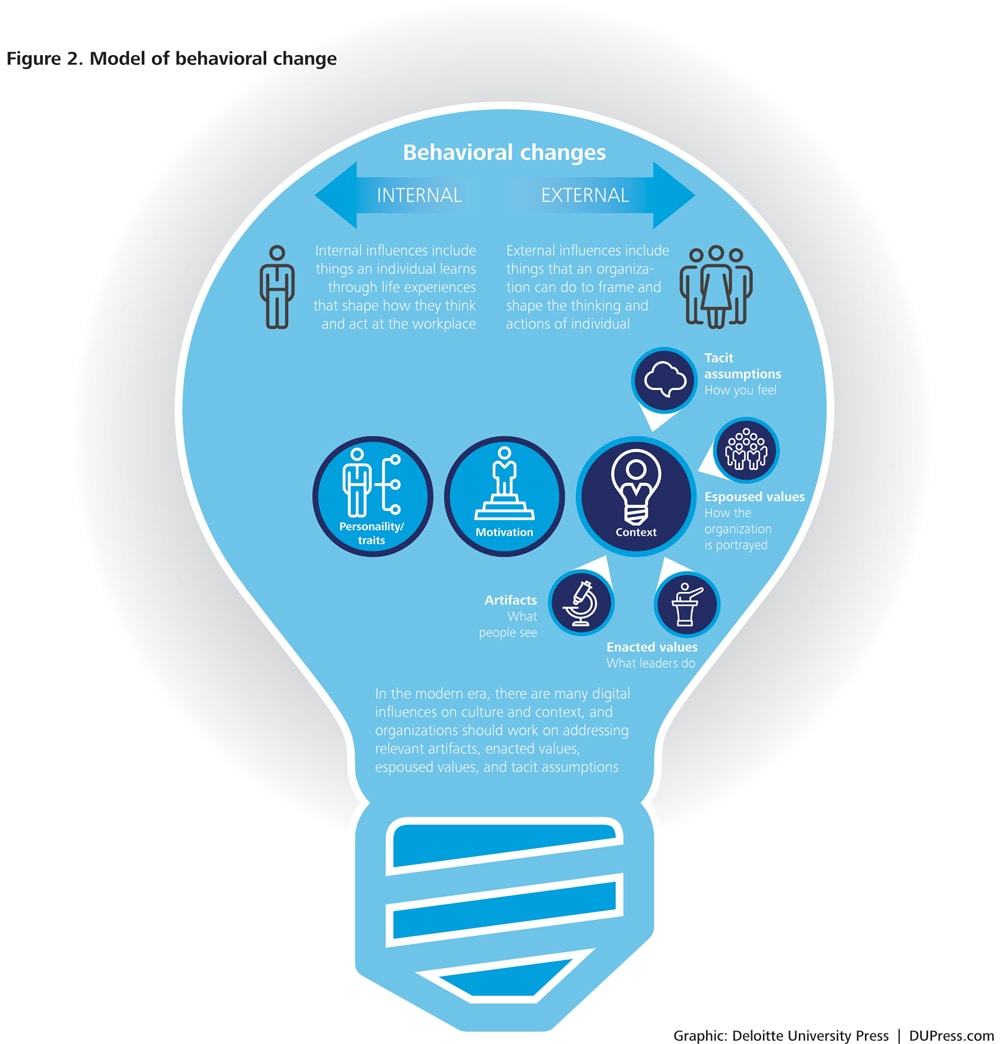

While culture seems to be an amorphous concept, it is made up of the objects, conversations, and thoughts we have every day. Organizational culture is a complex mix of physical artifacts with individual and shared beliefs, each influencing the other. There are multiple elements to culture, both tangible and intangible. For example, museums are increasingly returning objects to native peoples because they are “cultural artifacts,” physical reminders of intangible activities and beliefs. Just as a ceremonial pot may be of cultural significance to a native tribe, so too can the reminder signs, meetings invitations, and workspaces be artifacts of an organizational culture. They are the physical reminders of a culture and the tools with which we enact that culture.

But artifacts alone are not culture. Organizational culture also depends on the individual beliefs or tacit assumptions of each employee, as well the shared norms or espoused values of an organization. Those intangible values and assumptions become the tangible artifacts of culture through the group’s enacted values, or those values and norms exhibited by the group.

Motivation: What about rewards and punishments?

So if not intrinsic personality traits, what about the second factor in decision making, motivation? If these environmental factors are tipping an employee’s scales of judgment toward noncompliance, one immediate solution may be to apply additional external factors to rebalance those scales. These factors come in two forms: incentives to encourage appropriate behavior, and penalties to punish improper behavior. While rewards and punishments do influence behavior, they cannot be the only solution. In fact, penalties in particular may be less effective than we tend to believe. Used alone, excessive penalties can actually be counterproductive, increasing the frequency of employees breaking the rules.9

The limitation on the success of incentive/penalty schemes is their relationship to the wider organizational culture.10 If penalties are out of step with the prevailing organizational culture, culture will have a greater influence over an individual’s behavior.11 For example, many companies that issue laptops to employees also issue locks to minimize theft. While these organizations have policies and penalties in place to encourage employees to lock their laptops to a desk, the organizational culture of doing work quickly and on the move often provides a stronger pull in the other direction. Walk around the average work floor and count the number of laptop locks in use to get a sense of which is more powerful, incentives or culture.12

So while incentives/penalties may be effective, if they do not fit within and reinforce the existing culture, they are likely to be marginalized, with compliance minimized, and perhaps even actively rebelled against.13 This is the crux of the problem: If an organization aims to improve the security behavior of employees, it must understand and change its organizational culture to support and promote those behaviors.

The cultural context

The most challenging aspect of organizational culture is that it is a complex mix of a number of interdependent elements.14 Figure 2 and the sidebar, “What is culture, anyway?” show the four major elements of culture in the abstract, but a real-world example may help you see how they all come together. Think about entering a secure facility, for example, an airport. At the jetway door, there is a sign reminding every employee to badge-in individually and not to “tailgate” others through the door. This sign is evidence that the organization has a shared espoused value to restrict access to aircraft to only authorized personnel. Inspired by that goal, an airport manager may create a badging program identifying who is authorized for which areas and demonstrating an enacted commitment to the espoused goal. One artifact of this badging program is the badges themselves and another is the “no tailgating” sign at the gate. But the badges and sign alone are not culture. Compliance with that sign may be informed by how the pilots or employees feel about the organization, its goals, and the manager who created the program—a complex web of interactions.

With this in mind, it is clear that you cannot simply change one element and expect an entire organizational culture to change. We have all seen failed attempts to shift organizational culture in which the only actions taken were putting up posters or sending out emails. Likely those efforts failed because they were limited to just these tactics, and, as we saw with the laptop locks, when one thing goes against a larger cultural behavior, it is likely to lose. Rather, to successfully change culture, leaders must take advantage of the interactions between the elements, not work against them.15

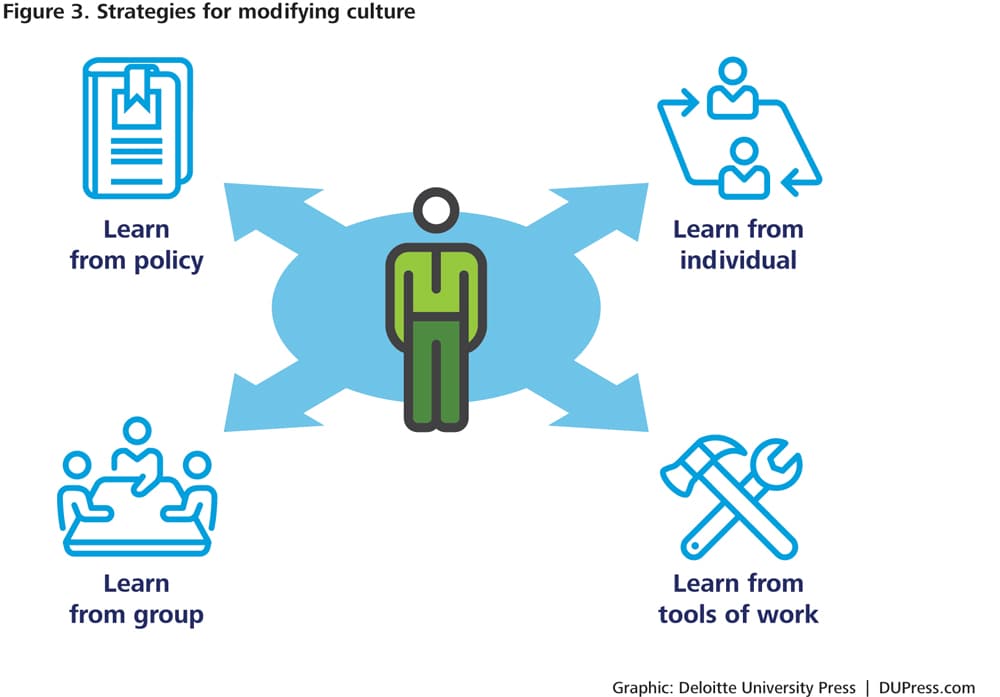

But how can an organization ensure that this occurs? To simplify the problem, imagine that a new employee has just come to work for an organization with a strong security culture. Now he must learn the new culture and begin to act accordingly. The new employee becomes familiar with each element of the organizational culture in a different way (see figure 3).16

- Learn from policy: First, he can read the security policies (espoused values), but lacking information about how the rest of the group thinks and actually does work, this alone will likely not be completely effective.

- Learn from a mentor or peer: He can learn from another individual in the organization through socialization. One potential way to reinforce this concept may be to assign an onboarding buddy or coach; the new employee can begin to take social cues from others within the organization (mirroring the actions that reveal their tacit assumptions).17

- Learn from the group: Similarly, he can also learn, not just from one employee, but from a group through the regular day-to-day interactions on the job. In doing so, the employee can see how others think and feel about the work or about security policies (enacted values), and can begin to form his own ideas for how the work should be done.

- Learn from the work: Finally, from being surrounded by the tools (or artifacts) of doing work every day, the employee can begin to internalize the message signified by the artifacts, and begin to believe—and act—accordingly.

If these four learning dimensions are how a new employee learns the ropes, then an organization must pay attention to all four strategies if it is to successfully align all the elements of organizational culture and create a more secure climate.

To see how organizations apply these strategies in real life to change organizational culture and improve security, the following success stories may be helpful.

Internalizing: From artifacts to assumptions

Perhaps some of the most tightly knit and well-known organizational cultures are those of the armed forces. Largely due to the cultural norms established through training, the military is able to get volunteers to willingly put their lives in danger, a situation that would make little sense if we were just considering a traditional economic model of incentives/punishments. Therefore, when looking to strengthen the organizational culture of any group, it may be worth considering how the armed forces craft their cultures.

In one study focusing on West Point Army cadets, researchers point to the beginning of cultural formation on the first day of training, called Reception Day or R-Day. The uniforms, haircuts, and stress of R-Day initiates a process of internalization by which cadets take the shared values of the Army and incorporate them into their own identity. Artifacts such as uniforms, marching, and specific phrases of speech all serve to consistently reinforce the shared values of the group. Slowly over time, those values become part of the cadets’ own tacit assumptions about the organization, their relationship to it, and even become intertwined with their self-images.18

In a different example of internalization, a Marine Corps veteran related a story about internalizing values around shared responsibility for the base grounds.19 He was walking with a senior leader across a parking lot after a meeting, and the leader spotted some litter in the grass next to the lot. He told the junior officer to pick it up, explaining that the base belonged to all of them and they needed to take care of every inch of it. The veteran said that the first time, he picked up the trash because he was told to. A few days later, walking across the same parking lot, he saw some trash again and picked it up so that he would not get reprimanded in case the senior leader was watching. A third time he picked up trash out of habit, but the fourth time he did it because he truly believed that it was his parking lot and he needed to take care of it. A fifth time he was walking across the lot with a more junior Marine and noticed some trash. He told the junior Marine to pick it up, just as he had been told by the senior leader, offering the same explanation he was given and passing on the cultural value.

By internalizing the shared values of an organization, the individual is less likely to act against the norms of behavior of that organization, less likely to break the rules. If your thoughts and identity are intertwined with those of the group, acting against the group actually hurts you as well.20 In this light, the high-profile leaks of classified military documents were not just failures of security procedure, but perhaps also of the organizational culture that promoted following those procedures.

Reinforcement: From assumptions to artifacts

The military is a special case when it comes to organizational culture. It has the ability to dictate the speech, dress, and even living conditions of its employees. So it is no surprise that organizations in other industries pursue different strategies to strengthen culture beyond internalization. A common strategy in these cases involves taking the organizational goals and ensuring that they are supported and reinforced at every level, from senior leadership down to the front line.

Safety programs in the oil and gas industry are a fine example of this. Beyond the individual costs in injuries and lives, accidents can have ecological, financial, and brand impacts that can be difficult for a company to overcome. As a result, safety is a top priority in this industry. Safety protocols are reinforced at every level, both in the field and in the office. Managers are evaluated not only on their financial or operational metrics, but also on safety statistics. Every meeting begins with a safety plan, and safety drills to practice important skills are held routinely. Safety is reinforced in small actions even down to the signs reminding workers to hold onto the handrails on drilling platforms.21

However, just passively reinforcing culture is not enough. Leaders must actively reinforce culture as well by rewarding positive behavior and correcting errors. Because it is difficult to predict exactly what types of issues may arise, often this active reinforcement comes down to shoe-leather leadership—just remaining involved. But with the increasing sophistication of computer models, an increasing number of risk factors can be identified digitally via employee monitoring.

In the financial services industry, for example, the insider threat is not just isolated to the loss of sensitive data, but can include rogue traders whose unauthorized actions can cost a company millions.22 The traditional approach to avoiding these dangerous trades is to set position limits, which hamstring traders’ ability to bet too much and risk the company. However, research suggests that position limits may not be completely effective and that, motivated by the desire to increase their “star power,” rogue traders often actively work to conceal their losses.23 Even worse, once they have executed a few rogue trades, these traders may go past a point of no return, where the only way to cover their tracks is with increasingly large fraudulent accountings. In this case, what is required are not simple policy limits forbidding bad behavior, but models that track trades and can identify suspicious trades or money transfers.24 With such tools, bank leaders can actively monitor and engage with the traders they manage to identify and address risky trades before they pile up and sink the company. Perhaps more importantly, these tools can also help the traders themselves by identifying and rewarding those who trade responsibly, and helping to balance the incentives for those tempted to make borderline or fraudulent trades.

Employee monitoring is known to improve compliance with expectations, but it is also often framed in a negative context. However, these two examples reveal that it can be a part of a healthy organizational culture where the monitoring is not a sign of management’s distrust of employees, but rather is used to improve employees’ safety and/or career development. Clearly articulating what those benefits are to employees is a key element not just for compliance with expectations, but also acceptance of the new technology. As with all things that deal with social perceptions, the exact approach and communication of employee monitoring should be tailored to the industry and even culture of the country.25

Realizing the benefits

Organizational culture is an important contributor to achieving a variety of security goals, from improving the safety of sensitive data, to limiting fraud, to promoting physical safety and security. Focusing on organizational culture can create lasting, measurable improvements to the physical security, information security, and cybersecurity of any organization. By integrating an understanding of the elements of culture, leaders can even improve the effectiveness of existing security programs by reinforcing the message in all of the ways employees receive them.

In fact, by adopting this approach to security, organizations may find themselves not just more secure, but happier, more innovative, and more productive.26 With culture playing such a crucial role in how employees regard the organization and their work, it is perhaps no surprise that organizational cultures that emphasize innovation are associated with more successful implementation of breakthroughs, faster technological adoption, and greater overall performance than companies that do not.27 But research also suggests that a strong culture can also make employees perform better at any task; that the same methods used to improve security culture can also have a measurable increase in productivity. Regardless of which method of culture change is used, over time, the effect is the same. Each employee’s tacit assumptions slowly become more aligned to the goals and activities of the organization. While we have illustrated how this can be used to improve security, a number of research projects have shown that the alignment of individual and group goals or norms is key to increasing productivity.28 An individual’s identification within a group is a strong driver to increased productivity, even more than factors such as clarity of task or likelihood of individual reward. This is a big reason why companies with strong cultures tend to outperform other companies.29 In other words, any investment in strengthening organizational culture, regardless of if it is directed at security, innovation, or merely belonging, is likely to earn back the investment through improved performance.

Given these clear benefits, what are some immediate steps leaders can take to improve the security culture of their organizations? Changing organizational culture involves a two-step process: assessing culture and transforming culture. To begin, leaders at all levels can use the model of organizational culture presented here to assess their current starting point. This should help them understand where elements of security culture may already exist within their organizations, and where they may need to be reinforced. Useful steps include:

- Using surveys of employee engagement or command climate can help leaders gain an understanding of baseline individual and group values within an organization. Simple survey questions such as, “I am proud to work for my organization,” “I receive the training I need to do my job well,” or “I feel part of a cohesive team,” can measure the level of employee engagement. Employee engagement is not only a useful tool for determining how cohesive an organization’s culture is, it is also a key indicator of how employees may react to any efforts to change that culture.

- Adding visioning sessions and other workshop-style events to help identify the current state of the organization and determine if it is aligned to the group’s goals.

- Aligning the existing security strategy and plans with the gaps identified in the visioning session. This will provide the foundation for a roadmap to change the organizational culture.

With a view of the cultural starting point, leaders can then embark on a transformational plan to improve key aspects of the culture using the following steps:

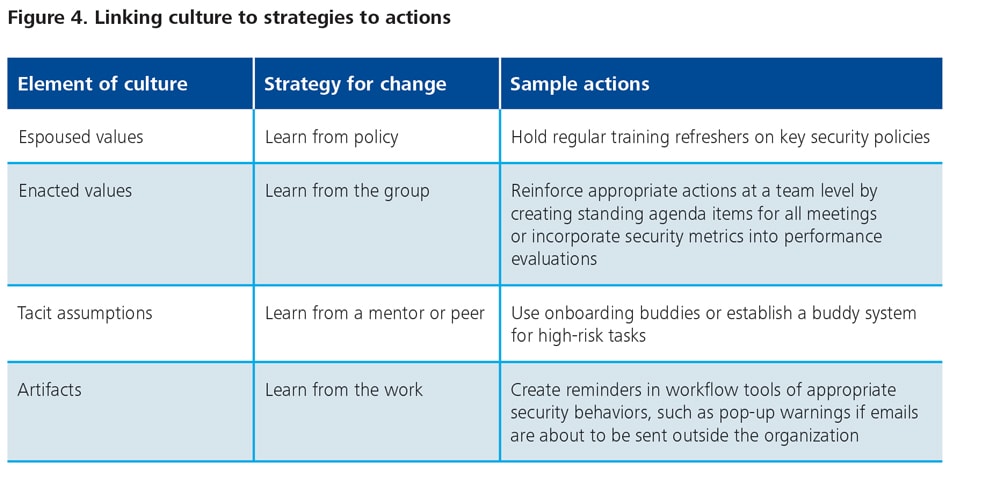

- Based on where the existing culture does not support goals, leaders can select from the right goals and mix and match the right tools to form a strong culture (see figure 4).

- Create a security culture task force or study group with representation from all levels to aid in the design of new artifacts or programs.

- Utilize common organizational change management tools such as change roadmaps and communication plans to help support these efforts.

Sailing into the future

Organizational culture is as living and breathing a thing as the people who embody it. Culture is not something that we can fix, like a leaky pipe, and then ignore; rather, it represents a powerful lens for leaders to continually examine their organizations to keep them healthy, productive, and, above all, secure. The leaders of the Royal Navy understood that the defense of their ships did not stop with the preparation of wood and cannons, but that most of all, it relied on the sailors themselves. So they created strong organizational cultures to support proper behavior, even in difficult situations. While ships have changed to networks, and cannonballs to digital bits, human nature remains the same. Therefore, the same time-tested approach to building security can still apply to your organization today.