CIO as chief integration officer has been saved

CIO as chief integration officer A new charter for IT

30 January 2015

- Peter Vanderslice

CIOs can help drive innovation by serving as a link between the business strategy and the IT agenda—fusing the vision for tomorrow with the realities of today.

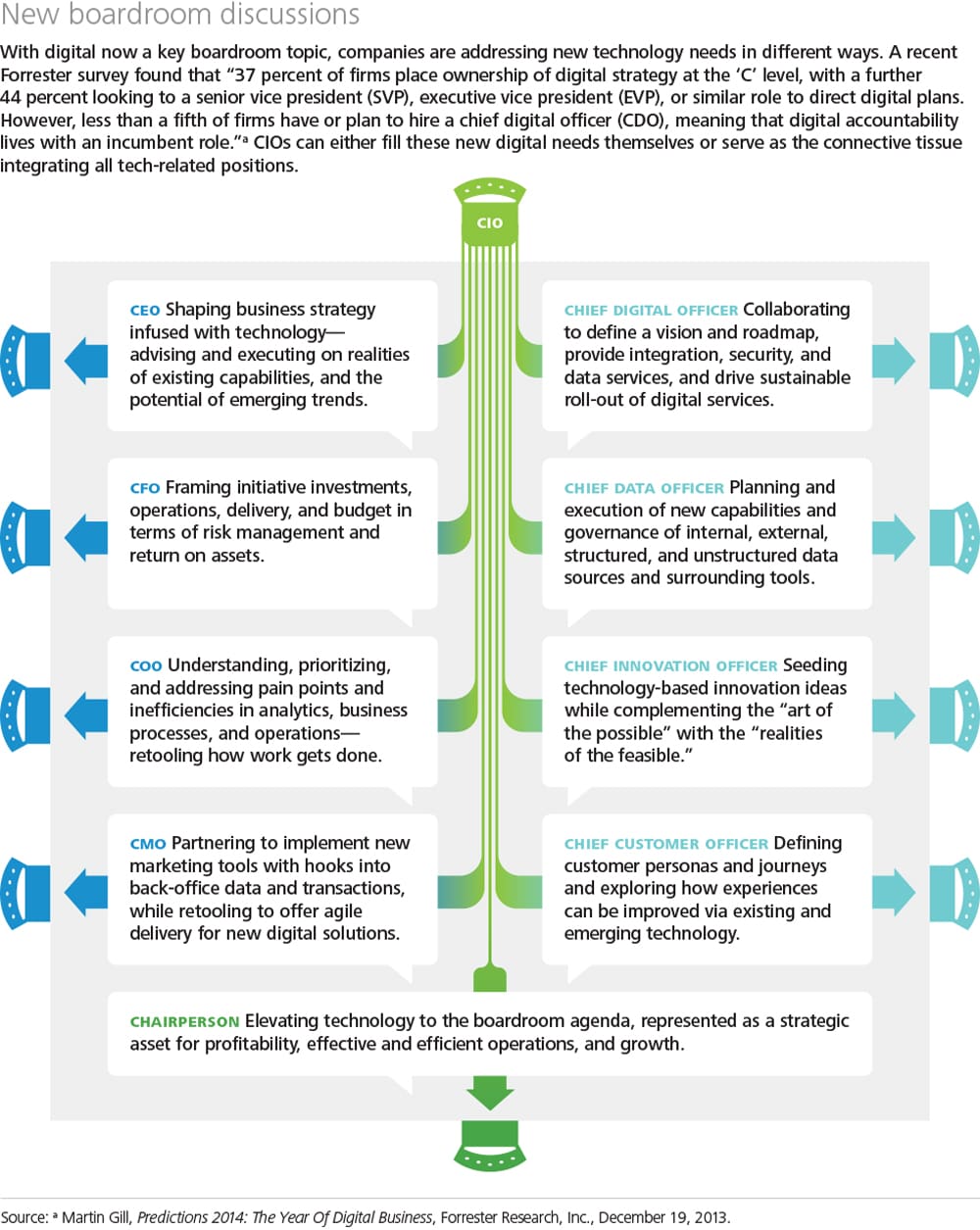

As technology transforms existing business models and gives rise to new ones, the role of the CIO is evolving rapidly, with integration at the core of its mission. Increasingly, CIOs need to harness emerging disruptive technologies for the business while balancing future needs with today’s operational realities. They should view their responsibilities through an enterprise-wide lens to help ensure critical domains such as digital, analytics, and cloud aren’t spurring redundant, conflicting, or compromised investments within departmental or functional silos. In this shifting landscape of opportunities and challenges, CIOs can be not only the connective tissue but the driving force for intersecting, IT-heavy initiatives—even as the C-suite expands to include roles such as chief digital officer, chief data officer, and chief innovation officer. And what happens if CIOs don’t step up? They could find themselves relegated to a “care and feeding” role while others chart a strategic course toward a future built around increasingly commoditized technologies.

For many organizations, it is increasingly difficult to separate business strategy from technology. In fact, the future of many industries is inextricably linked to harnessing emerging technologies and disrupting portions of their existing business and operating models. Other macro-level forces such as globalization, new expectations for customer engagement, and regulatory and compliance requirements also share a dependency on technology.

Learn more

View all 2015 technology trends

Create and download a custom PDF of the Business Trends 2015 report.

As a result, CIOs can serve as the critical link between business strategy and the IT agenda, while also helping identify, vet, and apply emerging technologies to the business roadmap. CIOs are uniquely suited to balancing actuality with inspiration by introducing ways to reshape processes and potentially transform the business without losing sight of feasibility, complexity, and risk.

But are CIOs ready to rumble? According to a report by Harvard Business Review Analytic Services, “57 percent of the business and technology leaders surveyed view IT as an investment that drives innovation and growth.”1 But according to a Gartner report, “Currently, 51 percent of CIOs agree that the torrent of digital opportunities threatens both business success and their IT organizations’ credibility. In addition, 42 percent of them believe their current IT organization lacks the key skills and capabilities necessary to respond to a complex digital business landscape.”2

To remain relevant and become influential business leaders, CIOs should build capabilities in three areas. First, they should put their internal technology houses in order; second, they should leverage advances in science and emerging technologies to drive innovation; and finally, they need to reimagine their own roles to focus less on technology management and more on business strategy.

In most cases, building these capabilities will not be easy. In fact, the effort will likely require making fundamental changes to current organizational structures, perspectives, and capabilities. The following approaches may help CIOs overcome political resistance and organizational inertia along the way:

- Work like a venture capitalist. By borrowing a page from the venture capitalist’s playbook and adopting a portfolio management approach to IT’s balance sheet and investment pool, CIOs can provide the business with greater visibility into IT’s areas of focus, its risk profile, and the value IT generates.3 This approach can also help CIOs develop a checklist and scorecard for getting IT’s house in order.

- Provide visibility into the IT “balance sheet.” IT’s balance sheet includes programs and projects, hardware and software assets, data (internal and external, “big” and otherwise), contracts, vendors, and partners. It also includes political capital, organizational structure, talent, processes, and tools for running the “business of IT.” Critical to the CIO’s integration agenda is visibility of assets, along with costs, resource allocations, expected returns, risks, dependencies, and an understanding of how they align to strategic priorities.

- Organize assets to address business priorities. How well are core IT functions supporting the day-to-day needs of the business? Maintaining reliable core operations and infrastructure can establish the credibility CIOs need to elevate their missions. Likewise, spotty service and unmet business needs can quickly undermine any momentum CIOs have achieved. Thus, it is important to understand the burning issues end users face and then organize the IT portfolio and metrics accordingly. Also, it’s important to draw a clear linkage between the balance sheet, today’s operational challenges, and tomorrow’s strategic objectives in language everyone can understand. As Intel CIO Kim Stevenson says, “First, go after operational excellence; if you do that well, you earn the right to collaborate with the business, and give them what they really need, not just what they ask for. Master that capability, and you get to shape business transformation, not just execute pieces of the plan.”

- Focus on flexibility and speed. The business wants agility—not just in the way software is developed, but as part of more responsive, adaptive disciplines for ideating, planning, delivering, and managing IT. To meet this need, CIOs can direct some portions of IT’s spend toward fueling experimentation and innovation, managing these allocations outside of rigid annual budgeting or quarterly planning cycles. Business sponsors serving as product owners should be embedded in project efforts, reinforcing integration between business objectives and IT priorities. Agility within IT also can come from bridging the gap between build and run—creating an integrated set of disciplines under the banner of DevOps.4

For CIOs to become chief integration officers, the venture capitalist’s playbook can become part of the foundation of this transformation—setting up a holistic view of the IT balance sheet, a common language for essential conversations with the business, and a renewed commitment to agile execution of the newly aligned mission. These capabilities are necessary given the rapidly evolving technology landscape.

Harness emerging technologies and scientific breakthroughs to spur innovation

One of the most important integration duties is to link the potential of tomorrow to the realities of today. Breakthroughs are happening not just in IT but in the fields of science: materials science, medical science, manufacturing science, and others. The Exponentials at the end of this report shine a light on some of the advances, describing potentially profound disruption to business, government, and society.

- Create a deliberate mechanism for scanning and experimentation. Define processes for understanding the “what,” distilling to the “so what,” and guiding the business on the “now what.” As Peter Drucker, the founder of modern management, says, “innovation is work”—and much more a function of the importing and exporting of ideas than eureka moments of new greenfield ideas.5

- Build a culture that encourages failure. Within and outside of IT, projects with uncharted technologies and unproven effects inherently involve risk. To think big, start small, and scale quickly, development teams need CIO support and encouragement. The expression “failing fast” is not about universal acceptance and celebrating failure. Rather, it emphasizes learning through iteration, with experiments that are designed to yield measurable results—as quickly as possible.6

- Collaborate to solve tough business problems. Another manifestation of “integration” involves tapping into new ecosystems for ideas, talent, and potential solutions. Existing relationships with vendors and partners are useful on this front. Also consider exploring opportunities to collaborate with nontraditional players such as start-ups, incubators, academia, and venture capital firms. Salim Ismail, Singularity University’s founding executive director, encourages organizations to try to scale at exponential speed by “leveraging the world around them”—tapping into diverse thinking, assets, and entities.7

An approach for evaluating new technology might be the most important legacy a CIO can leave: institutional muscle memory for sifting opportunities from shiny objects, rapidly vetting and prototyping new ideas, and optimizing for return on assets. The only constant among continual technology advances is change. Providing focus and clarity to that turmoil is the final integration CIOs should aspire to—moving from potential to confidence, and from possibility to reality.

Become a business leader

The past several years have seen new leadership roles cropping up across industries: chief digital officer, chief data officer, chief growth officer, chief science officer, chief marketing technology officer, and chief analytics officer, to name a few. Each role is deeply informed by technology advances, and their scope often overlaps not only with the CIO’s role but between their respective charters. These new positions reflect burgeoning opportunity and unmet needs. Sometimes, these needs are unmet because the CIO hasn’t elevated his or her role to take on new strategic endeavors. The intent to do so may be there, but progress can be hampered by credibility gaps rooted in a lack of progress toward a new vision, or undermined by historical reputational baggage.

- Actively engage with business peers to influence their view of the CIO role. For organizations without these new roles, CIOs should consider explicitly stating their intent to tackle the additional complexity. CIOs should recognize that IT may have a hard time advancing their stations without a positive track record for delivering core IT services predictably, reliably, and efficiently.

- Serve as the connective tissue to all things technology. Where new roles have already been defined and filled, CIOs should proactively engage with them to understand what objectives and outcomes are being framed. IT can be positioned not just as a delivery center but as a partner in the company’s new journey. IT has a necessarily cross-discipline, cross-functional, cross-business unit purview. CIOs acting as chief integration officers can serve as the glue linking the various initiatives together—advocating platforms instead of point solutions, services instead of brittle point-to-point interfaces, and IT services for design, architecture, and integration—while also endeavoring to provide solutions that are ready for prime time through security, scalability, and reliability.

Lessons from the front lines

Look inside IT

When asked recently about the proliferation of chiefs in the C-suite—chief digital offer, chief innovation officer, etc.—and the idea that CIOs could assume the role of “chief integration officer” by providing the much-needed connective tissue among many executives, strategies, and agendas, Intel Corp.’s CIO Kim Stevenson offered the following opinion: “The CIO role is unique in that it is defined differently across companies and industries. No two CIOs’ positions are the same, as opposed to chief financial officers, legal officers, and other C-suite roles. I don’t like it when people try to rename the CIO role. It contributes to a general lack of understanding about the role—and about what companies should expect from their CIOs.”

Monikers aside, Stevenson occasionally offers the following advice to CEOs and boards who are pondering the future amid tremendous technology-driven disruption: “If you need all those C-suite roles, you probably don’t have the right CIO.”

The “right CIO” is one who first achieves operational excellence by keeping the lights on, all critical IT positions filled, and all systems running at peak performance. At Intel, operational excellence of core business processes—satisfying day-to-day needs—has earned IT the right to collaborate with business leaders to identify solutions needed to achieve their goals.

It is through such collaboration that CIOs can elevate and broaden their roles. That means working with business leaders to not just give them what they ask for but helping them figure out what they really need. “Your internal customers have to want what IT is selling,” Stevenson notes, and to achieve this, CIOs should work with business leaders to create shared objectives and to expand expectations beyond incremental improvements to helping drive transformation. In one meeting with a senior vice president (SVP), Stevenson received the feedback: “We’re happy with everything you are doing right now.” When Stevenson and the SVP discussed where the function was strategically headed, several critical efforts were identified—new capabilities that likely couldn’t be delivered without IT. Because of the trust earned through more tactical collaboration, a more ambitious set of priorities was agreed upon.

Intel also tries to measure IT’s success not on its ability to provide a needed solution by a specific deadline but on the shared outcome of the initiative. The goal is for IT and its customer to be held responsible for achieving the same outcome—aligning priorities, expectations, and incentives.

Finally, through collaboration defined by shared objectives and outcomes, CIOs earn the right to influence how their companies will take advantage of disruptive change. At Intel, Stevenson recognized such an opportunity with the company’s mobile system-on-a-chip (SOC). The team looked at the product life cycle, from requirements to production, analyzing the entire process to understand why it took so long to get the company’s SOCs to market compared with competitors. Working closely with business units and the organization that oversees SOC production, Stevenson and her IT team identified bottlenecks and set their priorities for increasing throughput. The business units chose 10 SOCs to focus on, and IT came up with a number of improvements, ranging from basic (determining whether there was enough server space for what needed to be done) to complex (writing algorithms).

The outcome of this collaborative effort exceeded expectations. In 2014, the company saw production times for the targeted SOC products improve for one full quarter, in some cases for almost two. “That was huge for us,” said Stevenson. “The SOC organization set high expectations for us, just as we did for them. In the wake of our shared success, their view of IT has gone from one of ‘get out of my way’ to ‘I never go anywhere without my IT guys.’”

From claims to innovation

Like many of its global peers, AIG faces complex challenges and opportunities as the digital economy flexes its muscles. At AIG, IT is viewed not just as a foundational element of the organization, but also as a strategic driver as AIG continues its transformation to a unified, global business. AIG’s CEO, Peter Hancock, is taking steps to integrate the company’s IT leaders more deeply into how its businesses are leveraging technology. Shortly after assuming his post, Hancock appointed a new corporate CIO who reports directly to Hancock and chairs the company’s innovation committee. Previously, the top IT role reported to the chief administration officer.

AIG’s claim processing system, OneClaim™, is emblematic of the more integrated role IT leaders at the company can play. Peter Beyda, the company’s CIO for claims, is replacing AIG’s many independent claims systems with a centralized one that operates on a global scale. The mandate is to be as global as possible while being as local as necessary. Standardized data and processes yield operational efficiencies and centralized analytics across products and geographies. However, IT also responds to the fast-paced needs of the business. In China, for example, package solutions were used to quickly enter the market ahead of the OneClaim deployment—reconciling data in the background to maintain global consistency and visibility. AIG has deployed OneClaim in 20 countries and anticipates a full global rollout by 2017. The project is raising the profile of IT leadership within the company and the critical role these leaders can play in driving enterprise innovation efforts.

The OneClaim system also forms the foundation for digital initiatives, from mobile member services to the potential for augmenting adjustors, inspectors, and underwriters with wearables, cognitive analytics, or crowdsourcing approaches. IT is spurring discussions about the “art of the possible” with the business. OneClaim is one example of how AIG’s IT leadership is helping define the business’s vision for digital, analytics, and emerging technologies, integrating between business and IT silos, between lines of business, and between the operating complexities of today and the industry dynamics of tomorrow.

Digital mixology

Like many food and beverage companies, Brown-Forman organizes itself by product lines. Business units own their respective global brands. Historically, they worked with separate creative agencies to drive their individual marketing strategies. IT supported corporate systems and sales tools but was not typically enlisted for customer engagement or brand positioning activities. But with digital upending the marketing agenda, Brown-Forman’s CIO and CMO saw an opportunity to reimagine how their teams worked together.

Over the last decade, the company recognized a need to transform its IT and marketing groups to stay ahead of emerging technologies and shifting consumer patterns. In the early 2000s, Brown-Forman’s separate IT and marketing teams built the company’s initial website but continued to conduct customer relationship management (CRM) through snail mail. As social media began to explode at the turn of the decade, Brown-Forman’s marketing team recognized that closely collaborating with IT could be the winning ingredient for high-impact, agile marketing. While the external marketing agencies that Brown-Forman had contracted with for years were valuable in delivering creative assets and designs, marketing now needed support in new areas such as managing websites and delivering digital campaigns. Who better to team with than the IT organization down the hall?

IT and marketing hit the ground running: training, learning, and meeting with companies such as Facebook and Twitter. It was the beginning of the company’s Media and Digital group, which now reports to both the CMO and IT leadership. And more importantly, it was the creation of a single team that brought together advantages from both worlds. IT excelled at managing large-scale, complex initiatives, while marketing brought customer knowledge and brand depth. Their collaboration led to the development of new roles, such as that of digital program manager, who helped instill structure, consistency, and scale to drive repeatable processes throughout the organization.

As the teams worked together, new ideas were bootstrapped and brought to light. Take, for example, the Woodford Reserve Twitter Wall campaign, which originally required heavy investment dollars each year with a third party. The close interaction between marketing and IT led to the question: “Why can’t we do this ourselves?” Within a week, a joint IT-marketing team had used a cloud platform and open-source tools to recreate the social streaming display, promptly realizing cost savings and creating a repeatable product that could be tweaked for other markets and brands.

Fast-forward to today. Marketing and IT are teaming to provide Brown-Forman with a single customer view through a new CRM platform. Being able to share customer insight, digital assets, and new engagement techniques globally across brands is viewed as a competitive differentiator. The initiative’s accomplishments over the next few years will be contingent upon business inputs from the marketing team and innovation from IT to cover technology gaps.

The “one team” mentality between IT and marketing has put Brown-Forman on a path toward its future-state customer view. Along the way, the organization has reaped numerous benefits. For one, assets created by creative agencies can be reused by Brown-Forman’s teams through its scalable and repeatable platforms. Moreover, smaller brands that otherwise may not have had the budget to run their own digital campaign can now piggyback onto efforts created for the larger brands. The relationship fostered by IT and marketing has led to measurable return on investment (ROI)—and a redefined company culture that is not inhibited by the silos of department or brand verticals.

My take

Pat Gelsinger, CEO

VMware

I meet with CIOs every week, hundreds each year. I meet with them to learn about their journeys and to support them as they pursue their goals. The roles these individuals play in their companies are evolving rapidly. Though some remain stuck in a “keep the lights on and stick to the budget” mind-set, many now embrace the role of service provider: They build and support burgeoning portfolios of IT services. Still others are emerging as strategists and decision makers—a logical step for individuals who, after all, know more about technology than anyone else on the CEO’s staff. Increasingly, these forward-thinking CIOs are applying their business and technology acumen to monetize IT assets, drive innovation, and create value throughout the enterprise.

CIOs are adopting a variety of tactics to expand and redefine their roles. We’re seeing some establish distinct teams within IT dedicated solely to innovating, while others collaborate with internal line-of-business experts within the confines of existing IT infrastructure to create business value. Notably, we’ve also seen companies set up entirely new organizational frameworks in which emerging technology–based leadership roles such as the chief digital officer report to and collaborate with the CIO, who, in turn, assumes the role of strategist and integrator.

What’s driving this evolution? Simply put, disruptive technologies. Mobile, cloud, analytics, and a host of other solutions are enabling radical changes in the way companies develop and market new products and services. Today, the Internet and cloud can offer start-ups the infrastructure they need to create new applications and potentially reach billions of customers—all at a low cost.

Moreover, the ability to innovate rapidly and affordably is not the exclusive purview of tech start-ups. Most companies with traditional business models probably already have a few radical developers on staff—they’re the ones who made the system break down over the weekend by “trying something out.” When organized into small entrepreneurial teams and given sufficient guidance, CIO sponsorship, and a few cloud-based development tools, these creative individuals can focus their energies on projects that deliver highly disruptive value.

VMware adopted this approach with the development of EVO:RAIL, VMware’s first hyper-converged infrastructure appliance and a scalable, software-defined data-center building block that provides the infrastructure needed to support a variety of IT environments. To create this product, we put together a small team of developers with a highly creative team leader at the helm. We also provided strong top-down support throughout the project. The results were, by any definition, a success: Nine months after the first line of code was written, we took EVO:RAIL to market.

Clearly, rapid-fire development will not work with every project. Yet there is a noticeable shift underway toward the deployment of more agile development techniques. Likewise, companies are increasingly using application program interfaces to drive new revenue streams. Others are taking steps to modernize their cores to fuel the development of new services and offerings. Their efforts are driven largely by the need to keep pace with innovative competitors. At VMware, we are working to enhance the user experience.

Having become accustomed to the intuitive experiences they enjoy with smartphones and tablets, our customers expect us to provide comparable interfaces and experiences. To meet this expectation, we are taking a markedly different approach to development and design, one that emphasizes both art and technology. Our CIO has assembled development teams composed of artists who intuit the experiences and capabilities users want, and hard-core technologists who translate the artists’ designs into interfaces, customer platforms, and other user experience systems. These two groups bring different skill sets to the task at hand, but each is equally critical to our success.

As CIOs redefine and grow their roles to meet the rapidly evolving demands of business and technology, unorthodox approaches with strong top-down support will help fuel the innovation companies need to succeed in the new competitive landscape.

My take

Stephen Gillett

Business and technology C-suite executive

CIOs can play a vital role in any business transformation, but doing so typically requires that they first build a solid foundation of IT knowledge and establish a reputation for dependably keeping the operation running. Over the course of my career, I’ve held a range of positions within IT, working my way up the ranks, which helped me gain valuable experience across many IT fundamentals. As CIO at Starbucks, I took my first step outside of the traditional boundaries of IT by launching a digital ventures unit. In addition to leveraging ongoing digital efforts, this group nurtured and executed new ideas that historically fell outside the charters of more traditional departments. I joined Best Buy in 2012 as the president of digital marketing and operations, and applied some of the lessons I had learned about engaging digital marketing and IT together to adjust to changing customer needs.

My past experiences prepared me for the responsibilities I had in my most recent role as COO of Symantec. When we talked about business transformation at Symantec, we talked about more than just developing new product versions with better features than those offered by our competitors. True transformation was about the customer: We wanted to deliver more rewarding experiences that reflected the informed, peer-influenced way the customer was increasingly making purchasing decisions. Organizational silos can complicate customer-centric missions by giving rise to unnecessary technical complexity and misaligned or overlapping executive charters. Because of this, we worked to remove existing silos and prevent new ones from developing. Both the CIO and CMO reported to me as COO, as did executives who own data, brand, digital, and other critical domains. Our shared mission was to bring together whatever strategies, assets, insights, and technologies were necessary to surpass our customers’ expectations and develop integrated go-to-market systems and customer programs.

Acting on lessons I learned in previous roles, we took a “tiger team” approach and dedicated resources to trend sensing, experimentation, and rapid prototyping. This allowed us to explore what was happening on the edge of our industry—across processes, tools, technology, and talent—and bring it back to the core. CIOs can lead similar charges in their respective organizations as long as their goals and perspectives remain anchored by business and customer needs. They should also be prepared to advocate for these initiatives and educate others on the value such projects can bring to the business.

My advice to CIOs is to identify where you want to go and then take incremental steps toward realizing that vision. If you are the captain of a ship at sea, likely the worst thing you can do is turn on its center 180 degrees—you’ll capsize. Making corrections to the rudder more slightly gives the boat time to adjust—and gives you time to chart new destinations. Pick one or two projects you know are huge thorns in the sides of your customers or your employees, and fix those first. We started out at Symantec by improving mailbox sizes, creating new IT support experiences, and fixing cell phone reception on campus. We moved on to improving VPN quality and refreshing end-user computing standards by embracing “bring your own device,” while simultaneously building momentum to complete an ERP implementation. By solving small problems first, we were able to build up the organizational IT currency we needed to spend on bigger problems and initiatives.

When CIOs ask me about how they can get a seat at the table for big transformation efforts, I ask them about the quality of their IT organizations. Would your business units rate you an A for the quality of their IT experience? If you try to skip straight to digital innovation but aren’t delivering on the fundamentals, you shouldn’t be surprised at the lack of patience and support you may find within your company. A sign that you have built up your currency sufficiently is when you are pulled into meetings that have nothing to do with your role as CIO because people “just want your thinking on this”—which means a door is opening for you to have a larger stake in company strategy.

Cyber implications

In many industries, board members, C-suite executives, and line-of-business presidents did not grow up in the world of IT. The CIO owns a crucial part of the business, albeit one in which the extended leadership team may not be particularly well versed. But with breaches becoming increasingly frequent across industries, senior stakeholders are asking pointed questions of their CIOs—and expecting that their organizations be kept safe and secure.

CIOs who emphasize cyber risk and privacy, and those who can explain IT’s priorities in terms of governance and risk management priorities that speak to the board’s concerns, can help create strong linkages between IT, the other functions, and the lines of business. No organization is hacker-proof, and cyber attacks are inextricably linked to the IT footprint.8 Often, CIOs are considered at least partially to blame for incidents. Strengthening cyber security is another step CIOs can take toward becoming chief integration officers in a space where leadership is desperately needed.

Part of the journey is taking a proactive view of information and technology risk—particularly as it relates to strategic business initiatives. Projects that are important from a growth and performance perspective may also subject the organization to high levels of cyber risk. In the haste to achieve top-level goals, timeframes for these projects are often compressed. Unfortunately, many shops treat security and privacy as compliance tasks—required hoops to jump through to clear project stage gates. Security analysts are put in the difficult position of enforcing standards against hypothetical controls and policies, forcing an antagonistic relationship with developers and business sponsors trying to drive new solutions. As CIOs look to integrate the business and IT, as well as to integrate the development and operations teams within IT, they should make the chief information security officer and his or her team active participants throughout the project life cycle—from planning and design through implementation, testing, and deployment.

The CIO and his or her extended IT department are in a rare position to orchestrate awareness of and appropriate responses to cyber threats. With an integrated view of project objectives and technology implications, conversations can be rooted in risk and return. Instead of taking extreme positions to protect against imaginable risk, organizations should aim for probable and acceptable risk—with the CIO helping business units, legal, finance, sales, marketing, and executive sponsors understand exposures, trade-offs, and impacts. Organizational mind-sets may need to evolve, as risk tolerance is rooted in human judgment and perceptions about possible outcomes. Leadership should approach risk issues as overarching business concerns, not simply as project-level timeline and cost-and-benefit matters. CIOs can force the discussion and help champion the requisite integrated response.

In doing so, chief integration officers can combat a growing fallacy that having a mature approach to cyber security is incompatible with rapid innovation and experimentation. That might be true with a compliance-heavy, reactive mind-set. But by embedding cyber defense as a discipline, and by continuously orchestrating cyber security decisions as part of a broader risk management competency, cyber security can become a value driver—directly linked to shareholder value.

Where do you start?

There are concrete steps aspiring chief integration officers can take to realize their potential. Start with taking stock of IT’s current political capital, reputation, and maturity. Stakeholder by stakeholder, reflect on their priorities, objectives, and outcomes, and understand how IT is involved in realizing their mission. Then consider the following:

- Line of sight. Visibility into the balance sheet of IT is a requirement—not just the inventory but the strategic positioning, risk profile, and ROI of the asset pool. Consider budgets, programs, and projects; hardware and software; vendor relationships and contracts; the talent pool, organizational structure, and operating model; and business partner and other ecosystem influencers. Compare stakeholder priorities and the business’s broader goals with where time and resources are being directed, and make potentially hard choices to bring IT’s assets into alignment with the business. Invest in tools and processes to make this line of sight systemic and not a point-in-time study—allowing for ongoing monitoring of balance-sheet performance to support a living IT strategy.

- Mind the store. Invest in the underlying capabilities of IT so that the lights are not only kept on but continuously improving. Many potential areas of investment live under the DevOps banner: environment provisioning and deployment, requirements management and traceability, continuous integration and build, testing automation, release and configuration management, system monitoring, business activity monitoring, issue and incident management, and others. Tools for automating and integrating individual capabilities continue to mature. But organizational change dynamics will likely be the biggest challenge. Even so, it’s worth it—not only for improving tactical departmental efficiency and efficacy, but also to raise the IT department’s performance and reputation.

- All together now. Engage directly with line-of-business and functional leaders to help direct their priorities, goals, and dependencies toward IT. Solicit feedback on how to reimagine your IT vision, operating, and delivery model. Create a cadence of scheduled sit-downs to understand evolving needs, and provide transparency on progress toward IT’s new ambitions.

- Ecosystem. Knock down organizational boundaries wherever you can. Tap into your employees’ collective ideas, passions, and interests. Create crowd-based competitions to harness external experience for both bounded and open-ended problems. Foster new relationships with incubators, start-ups, and labs with an eye to obtaining not just ideas but access to talent. Set explicit expectations with technology vendors and services partners to bring, shape, and potentially share risk in new ideas and offerings. Finally, consider if cross-industry consortia or intra-industry collaborations are feasible. Integrate the minds, cycles, and capital of a broad range of players to amplify returns.

- Show, don’t tell. As new ideas are being explored, thinking should eclipse constraints based on previous expectations or legacy technologies. Interactive demos and prototypes can spark new ways of thinking, turning explanatory briefings into hands-on discovery. They also lend themselves better to helping people grasp the potential complexities and delivery implications of new and emerging techniques. The goal should be to bring the art of the possible to the business, informed by the realm of the feasible.

- Industrialize innovation. Consider an innovation funnel with layers of ideation, prototyping, and incubating that narrow down the potential field. Ecosystems can play an important role throughout—especially at the intersections of academia, start-ups, vendors, partners, government, and other corporate entities. Align third-party incentives with your organization’s goals, helping to identify, shape, and scale initiatives. Consider coinvestment and risk-sharing models where outsiders fund and potentially run some of your endeavors. Relentlessly drive price concessions for commoditized services and offerings, but consider adjusting budgeting, procurement, and contracting principles to encourage a subset of strategic partners to put skin in the game for higher-value, riskier efforts. Evolve sourcing strategies to consider “innovators of record” with a longer-term commitment to cultivating a living backlog of projects and initiatives.

- Talent. CIOs are only as good as their teams. The changes required to become a chief integration officer represent some seismic shifts from traditional IT: new skills, new capabilities and disciplines, new ways of organizing, and new ways of working. Define the new standard for the IT workers of the future, and create talent development programs to recruit, retain, and develop them.

Bottom line

Today’s CIOs have an opportunity to be the beating heart of change in a world being reconfigured by technology. Every industry in every geography across every function will likely be affected. CIOs can drive tomorrow’s possibilities from today’s realities, effectively linking business strategies to IT priorities. And they can serve as the lynchpin for digital, analytics, and innovation efforts that affect every corner of the business and are anything but independent, isolated endeavors. Chief integration officers can look to control the collisions of these potentially competing priorities and harness their energies for holistic, strategic, and sustainable results.