Internet of Things: From sensing to doing has been saved

Internet of Things: From sensing to doing Think big, start small, scale fast

25 February 2016

The IoT’s true value lies in its disruptive potential for reimagining business processes and, ultimately, rewiring business, government, and society. Realizing that potential means shifting IoT applications’ strategic focus toward not just sensing, but doing.

Increasingly, forward-thinking organizations are focusing their Internet of Things (IoT) initiatives less on underlying sensors, devices, and “smart” things and more on developing bold approaches for managing data, leveraging “brownfield” IoT infrastructure, and developing new business models. Meanwhile, others are developing human-impact IoT use cases for boosting food production, cutting carbon emissions, and transforming health services. What impact will IoT have on your business and on the people around you? Rapid prototyping can help you find out.

Explore

View Tech Trends 2016

Learn more about Deloitte Technology Consulting

Create and download a custom PDF of the 2016 report

Like a wildfire racing across a dry prairie, the Internet of Things (IoT) is expanding rapidly and relentlessly. Vehicles, machine tools, street lights, wearables, wind turbines, and a seemingly infinite number of other devices are being embedded with software, sensors, and connectivity at a breakneck pace. Gartner, Inc. forecasts that 6.4 billion connected things will be in use worldwide in 2016, up 30 percent from 2015, and that the number will reach 20.8 billion by 2020. In 2016, 5.5 million new things will get connected to network infrastructure each day.1

As IoT grows, so do the volumes of data it generates. By some estimates, connected devices will generate 507.5 zettabytes (ZB) of data per year (42.3 ZB per month) by 2019, up from 134.5 ZB per year (11.2 ZB per month) in 2014. (A zettabyte is 1 trillion gigabytes). Globally, the data created by IoT devices in 2019 will be 269 times greater than the data being transmitted to data centers from end-user devices and 49 times higher than total data center traffic.2

Even as businesses, government agencies, and other pioneering organizations at the vanguard of IoT take initial steps to implement IoT’s component parts—sensors, devices, software, connectivity—they run the risk of being overwhelmed by the sheer magnitude of the digital data generated by connected devices. Many will focus narrowly on passive monitoring of operational areas that have been historically “off the grid” or visible only through aggregated, batch-driven glimpses. To fully explore IoT’s potential, companies should think big, start small, and then scale fast.

Many enterprises already have unused IoT infrastructure built into their manufacturing machinery and IT software. We call these dormant components “brownfields”: Like roots, bulbs, and tubers in the soil, they need a good “rain” and a bit of tending to begin to thrive. Activating and connecting these brownfield components may help companies leapfrog some implementation steps and give their IoT initiatives a needed boost. In contrast, “greenfields”—enterprise environments with no preexisting IoT infrastructure—require basic seeding and a lot of tending over time to yield a new crop.

The value that IoT brings lies in the information it creates. It has powerful potential for boosting analytics efforts. Strategically deployed, analytics can help organizations translate IoT’s digital data into meaningful insights that can be used to develop new products, offerings, and business models. IoT can provide a line of sight into the world outside company walls, and help strategists and decision makers understand their customers, products, and markets more clearly. And IoT can drive so much more—including opportunities to integrate and automate business processes in ways never before possible.

Often overlooked is IoT’s potential for impacting human lives on a grand scale. For example, in a world where hunger persists, “smart farming” techniques use sensor data focused on weather, soil conditions, and pest control to help farmers boost crop yields. Meteorologists are leveraging hazard mapping and remote sensing to predict natural disasters farther in advance and with greater accuracy. The health care sector is actively exploring ways in which wearables might help improve the lives of the elderly, the chronically ill, and others. The list goes on and will continue to grow. We are only beginning to glimpse the enormity of IoT’s potential for making lives better.3

Sensing and sensibility

With so few detailed use cases, the sheer number of IoT possibilities makes it difficult to scope initiatives properly and achieve momentum. Many are finding that IoT cannot be the Internet of everything. As such, organizations are increasingly approaching IoT as the Internet of some things, purposefully bounded for deliberate intent and outcomes, and focused on specific, actionable business processes, functions, and domains.

The time has come for organizations to think more boldly about IoT’s possibilities and about the strategies that can help them realize IoT’s full disruptive potential. To date, many IoT initiatives have focused primarily on sensing—deploying and arranging the hardware, software, and devices to collect and transmit data. These preliminary steps taken to refine IoT approaches and tactics are just the beginning. The focus must shift from sensing to doing. How do inputs from sensors drive closed-loop adjustments and innovation to back-, middle-, and front-office business processes? Where can those processes become fully automated, and where can the core be reconfigured using feedback from connected devices and instrumented operations? What future IoT devices might open up new markets? To yield value, analytics-driven insights must ultimately boost the bottom line.

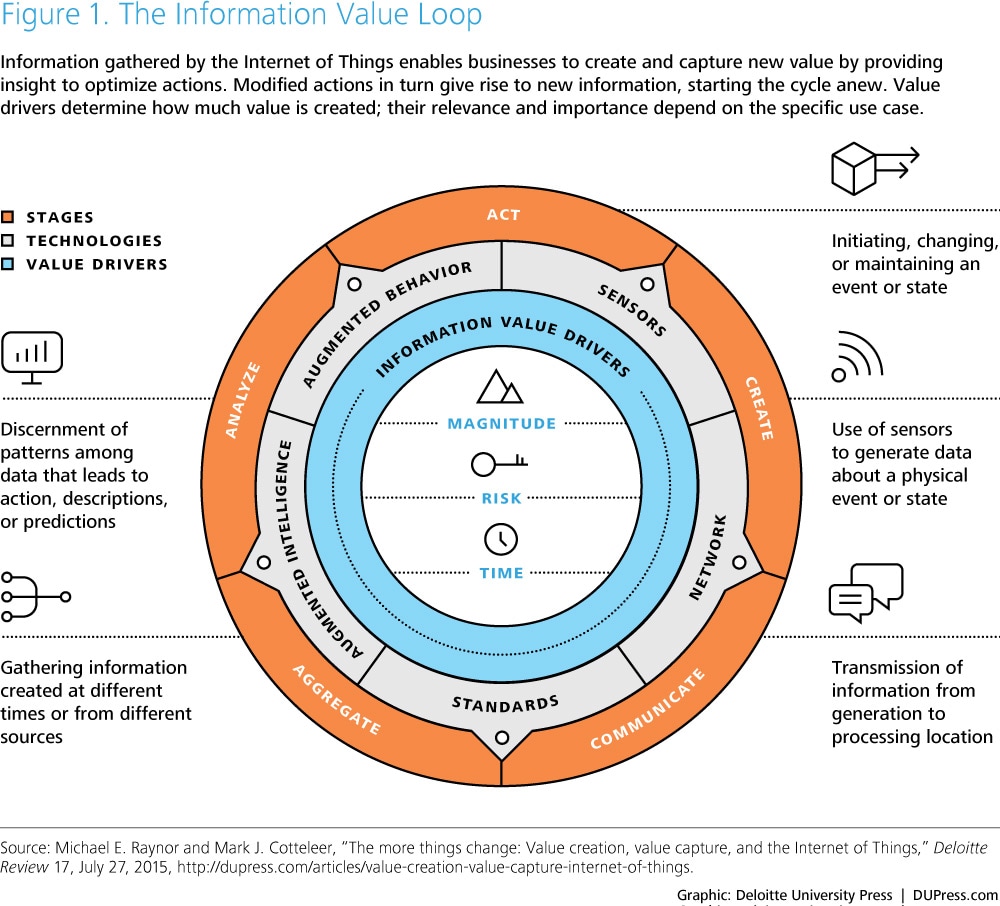

One strategy involves harnessing the information created by the IoT ecosystem to augment worker capabilities, a process modeled in the Information Value Loop. When built to enhance an individual’s knowledge and natural abilities and deployed seamlessly at the point of business impact, IoT, in tandem with advanced analytics, can help amplify human intelligence for more effective decision-making. For example, the ability to monitor the vital signs of elderly patients remotely and in real time will empower medical personnel to make more accurate care decisions more quickly. Even more profound, automated drug delivery systems may be triggered to respond to complicated signals culled from several parts of the care network.

Likewise, companies may harness data-driven insights to augment or amplify operational activity in the form of transforming business processes, reimagining core systems and capabilities, and automating controls. Eventually, robotic process automation and advanced robotics will monitor events, aggregate sensor data from numerous sources, and use artificial intelligence capabilities to determine which course of action they can take to deliver the most desirable outcome.4

Take manufacturing, for example. At a Siemens facility in Amberg, Germany, machines and computers handle roughly 75 percent of the value chain autonomously, with some 1,000 automation controllers in operation throughout the production line. Each part being manufactured has its own product code, which lets machines know its production requirements and which steps to take next. All processes are optimized for IT control, which keeps failure rates to a minimum. In this facility, employees essentially oversee production and technology assets, handling any unexpected incidents that may arise.5

Risks and rewards

As organizations work to integrate vast, disparate networks of connected devices into core systems and processes, there will likely be new security and privacy concerns to address. These concerns could be particularly acute in industries like health care—which may be aggregating, analyzing, and storing highly personal data gleaned from sensors worn by patients—or in manufacturing—where risks may increase as heavy industrial equipment or infrastructure facilities become increasingly connected. More data, and more sensitive data, available across a broad network means that risks are higher and that data breaches could pose significant dangers to individuals and enterprises alike.

With IoT, data security risks will very likely go beyond embarrassing privacy leaks to, potentially, the hacking of important public systems. Organizations will have to determine what information is appropriate for IoT enablement, what potential risks the assets and information may represent, and how they can ensure that solutions are secure, vigilant, and resilient.6

Similarly, as companies add additional inputs to their IT and IoT ecosystems, they will be challenged to create new rules that govern how action proceeds and data is shared. Opening up IoT ecosystems to external parties via APIs will give rise to even more risk-related considerations, particularly around security, privacy, and regulatory compliance.

Acting on the information created by the IoT—putting intelligent nodes and derived insights to work—represents the final, and most important, part of the IoT puzzle. Options for achieving this vary. Centralized efforts involve creating orchestration or process management engines to automate sensing, decisioning, and response across a network. Likewise, a decentralized approach typically focuses on automation: Rules engines would be embedded at end points, which would allow individual nodes to take action. In still other scenarios, IoT applications or visualizations could empower human counterparts to act differently.

Ultimately, the machine age may be upon us—decoupling our awareness of the world from the need for a human being to consciously observe and record what is happening. But machine automation only sets the stage; real impact, business or civic, will come from bringing together the resulting data and relevant sensors, things, and people to allow lives to be lived better, work to be done differently, and the rules of competition to be rewired.

With this in mind, organizations across sectors and geographies continue to pursue IoT strategies, driven by the potential for new insights and opportunities. By thinking more boldly about these opportunities and the impact they could have on innovation agendas, customer engagement, and competitiveness (both short- and long-term), companies will likely be able to elevate their IoT strategies beyond sensing to a more potentially beneficial stage of doing.

Lessons from the front lines

Caterpillar embraces the Internet of Big Things

At a remote mining region of western Australia, the IoT’s lofty potential meets the ground in a fleet of Caterpillar mining trucks—each boasting a 240-ton payload—that operate autonomously, 24 hours a day. These giant, driverless machines are outfitted with a variety of sensors that transmit information on oil pressure, filters, and other truck components via wireless connections (such as satellite, cellular, and others) back to Caterpillar headquarters in Peoria, IL, where an advisor monitors the equipment’s vital signs and can, when needed, make maintenance recommendations to the fleet’s owner.7

Though Caterpillar has been embedding sensors in its products for decades, only in the last few years has the global construction machinery and heavy equipment manufacturer begun exploring their potential application within the context of IoT. Today, IoT—or as they call it at Caterpillar, the “Internet of Big Things”—is a major strategic and technological focus, with the company exploring ways to mine IoT data that can then be used to develop predictive diagnostics tools, design products, and improve product performance.

For example, when compiled over time and analyzed, data generated by sensors embedded in construction-site machinery may be able to help engineers design heavy equipment that can accomplish more work with fewer passes. Fewer passes translates to reduced idle time, less operator fatigue, and lower fuel consumption. Ultimately, operating efficiently can help owners of Caterpillar equipment better serve their own customers.

Importantly, this information—combined with Caterpillar’s domain knowledge about heavy equipment and analytics—may help the company more accurately predict how specific pieces of equipment will perform in different environments and on specific types of jobs. To this end, Caterpillar recently announced it had entered into a technology agreement with analytics vendor Uptake to develop a predictive diagnostics platform to help customers monitor and optimize the performance of their fleets.8 Looking forward, Caterpillar expects IoT to help redefine business processes, drive better engagement with its customers, and evolve its products, services, and offerings.

Expanding the horizons of connected care

Some companies in the health care industry—including health plans, providers, medical device manufacturers, and software vendors—are testing the IoT waters with a number of sensor-driven big data initiatives that could transform the way patients and their providers manage acute health conditions.

One leading health care delivery system is currently developing a suite of mobile applications to track, record, and analyze biometric data generated by Bluetooth-enabled sensing devices worn by patients. These apps, each configured to monitor a specific medical condition, will share a common digital platform and feature APIs to encourage external development. Once deployed, they will be able to analyze sensor data and pair them with electronic medical records and other clinical information to help caregivers make faster—and more informed—decisions for patients. For example, a diabetic patient’s glucose readings would be streamed from a monitoring device to a mobile app on his or her phone or tablet, and then on to an integrated big data repository. Care coordinators would be alerted to unusual changes in the patient’s glucose levels so that they can take appropriate action, such as bringing the patient into the hospital for closer examination or adjusting his or her medications.

The organization piloted its diabetes monitoring application with almost 40,000 diabetic patients, demonstrating the viability of the platform. Next on the agenda: Expanding adoption of the diabetes pilot and extending the platform to support other conditions such as congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and high blood pressure, among others.

Living on “The Edge”

It’s morning in Amsterdam. An employee leaves her desk, walking casually toward a break room in the office building where she works. As she approaches, a custom app on her smartphone engages sensors embedded in a coffee machine, which immediately begins dispensing the employee’s preferred blend, complete with the add-ins she desires. When the employee arrives at the break room, her custom brew is waiting.

Welcome to life in “The Edge,” a futuristic office structure widely known as “the world’s smartest building.”9 Completed in 2014, The Edge—which is home to Deloitte Netherlands—is a showplace for leading-edge deployments of green architecture and advanced technology, including IoT applications. The innovative, connected lighting panels do more than sip minute amounts of voltage—they contain some 28,000 sensors that detect motion, light, temperature, humidity, and even carbon dioxide levels. It’s these sensors, providing real-time data, that make The Edge occupant-friendly.

The sensors allow facility managers to assess how and when certain parts of the building are being used. “In our building, IT and facilities management are a combined function,” explains Tim Sluiter, property manager, IT and Workplace Services, Deloitte Netherlands. In the short term, collected information can be used to determine where cleaning is and is not necessary on a given evening. Long term, emerging patterns showing light use in certain locales on certain days can lead to rooms or even entire floors being closed off to save energy.

IoT’s reach within this building extends far beyond lighting sensors. When employees approach The Edge’s high-tech garage, sensors identify their vehicles and then point them to available parking spots. Throughout the garage, sensor-equipped LED lights brighten and dim as drivers arrive and leave.

And that miraculous coffee app? It doubles as a digital office administrator that can assign daily workspaces that best fit users’ preferences and allows them to control the brightness of the lighting above their work surfaces and adjust the climate of their particular areas. It can direct people throughout the building—reading a meeting location from one’s online calendar, for example, and suggesting a route to get there. Employees can even use the app to track their progress in the on-site gym, where some of the fitness equipment actually feeds generated wattage into the building’s power grid.

Sluiter stresses that personal data generated by sensors and the app cannot be accessed by managers or anyone else. Privacy laws ensure that nobody can track a person’s whereabouts, monitor how many meetings he or she has missed, or see what times he or she is using the garage. “This building offers the technology to do certain things that would make tenants’ lives even easier,” Sluiter says. “But at the same time, it’s extremely important to protect people’s privacy and conform to the law.”

Those minimal barriers aren’t hindering The Edge’s reputation. “Our aim was to make The Edge the best place to work,” says Erik Ubels, director of IT and Workplace Services, Deloitte Netherlands. “Our meeting areas are filling up because every client and employee wants to experience this building. It’s not too small yet, but the economy is growing and the building is getting crowded. It’s possible we made it too popular.”10

My take

Sandy Lobenstein Vice president, connected vehicle technology and product planning, Toyota Motor Sales U.S.A., Inc.

At Toyota, we are all about mobility. I’m not talking just about car ownership. Mobility also includes public transportation, ridesharing, hoverboards, walking—anything that can get people from place A to place B more efficiently and safely. Mobility is truly multi-modal.

Toyota sees the IoT as an enabler of mobility, and we are moving very quickly to embrace its potential. Big data generated by sensors located throughout our cars will help engineers develop automobiles that think for themselves. Likewise, Dr. Gill Pratt, the chief executive officer of the Toyota Research Institute (TRI), and other researchers at TRI, will leverage IoT data to advance the science of intelligent cars as we move into the future mobility of autonomous vehicles. Progress in these areas will likely deliver autonomous connected cars that are reliable, safe, and fun to drive when you want to. The benefits that these innovations may eventually provide to everyday drivers, drivers with special needs, and to seniors could be life-enabling.

Toyota is no stranger to connected vehicle technologies; Lexus began offering connected vehicles in 2001. Today, all Lexus vehicles are connected, which enables services like Destination Assist, which links drivers to live agents who can provide directions for getting from point A to point B. Lexus also offers sensor-driven “car health” reports on current tire pressure, oil levels, and maintenance needs.

These IoT applications are just the beginning. Cars are mechanical products built with mechanical processes. Sensors are so small that we can place them virtually everywhere on cars. And what if you extend the same sensor technologies that monitor tires and brakes to the machines used to build vehicles on the manufacturing floor? These sensors could alert production leaders that there is a problem at a particular station, and that the parts manufactured at this station within a specific time frame will have to be rebuilt.

As for new offerings, it’s sometimes hard for companies to wrap their heads around the value of data. For example, early on, everyone assumed consumers wanted apps in cars. Very quickly, the auto industry realized that what customers actually wanted was for the apps on their phones to work in their cars. Across industries and sectors, strategists, designers, and decision makers typically believe that current approaches and systems are just fine. It takes vision—and a considerable amount of courage—to break with the way things have been done for the last 100 years and embrace some exotic technology that promises to deliver new opportunities.

But in this era of historic technological innovation, all companies must work aggressively to reinvent themselves by embracing new opportunities and compelling visions of the future. This is exactly what Toyota is doing with IoT and mobility.

I’m a car guy. In high school, I loved working under the hood of my car, which was the embodiment of leading-edge technology at that point in my life. For the last 15 years, we amateur mechanics have been distracted by other mechanical wonders—the kind everyone now spends their days staring at and speaking into. That’s about to change. Connectivity and cool new services are going to make cars come alive. All those people who’ve developed relationships with their smartphones are about to fall in love with cars all over again.

Cyber Implications

The IoT connects critical infrastructure that has been previously unconnected. As organizations begin harnessing these connections to create value, they may also add functionality to IoT networks that will make it possible to take control of devices and infrastructure remotely, and to automate monitoring and decision-making within certain parameters based on sensory data.

Make no mistake: As companies put IoT to work, the smart, connected objects they deploy offer tremendous opportunities for value creation and capture. Those same objects, however, can also introduce risks—many of them entirely new—that demand new strategies for value protection.

For example, every new device introduced in an IoT ecosystem adds a new attack surface or opportunity for malicious attack, thus adding additional threat vectors to a list that already includes protecting devices, data, and users. Likewise, identity spoofing—an unauthorized source gaining access to a device using the correct credentials—may present problems. And even if devices aren’t directly compromised but experience a hardware failure or a bug in the code, they should be able to fail in a safe way that doesn’t create vulnerabilities.

Moreover, the ecosystem structures that organizations often rightfully deploy can give rise to vulnerabilities. For example, IoT applications typically depend on the closely coordinated actions of multiple players, from vendors along the supply chain to clients, transport agencies, the showroom, and end-use customers. Vulnerabilities exist within each node and handoff seam between sensors, devices, or players. It should not be assumed that partners—much less customers—have robust mechanisms in place to maintain data confidentiality and guard against breaches.

In the face of these and other challenges, companies can take several steps to safeguard their ecosystems:11

- Work to define standards for interoperability: Internally, define data and service standards to guide consistent rollout within your organization’s boundaries. Also consider getting involved with consortia like the IIC12 to develop broader standards and ease connectivity and communication.

- Refactor with care: Retrofitting or extending functionality of old systems may be exactly what your IoT strategy needs. But when doing so, understand that there may be potential security, performance, and reliability implications, especially when pushing legacy assets into scenarios for which they weren’t designed. Whenever possible, use purpose-built components for the refactoring, engineered specifically for the use case.

- Develop clear responsibilities for the players in your ecosystem: Rather than sharing responsibility across a diffuse ecosystem, players should know where their responsibilities begin and end, and what they are charged with protecting. Assessing potential risks at each point—and making sure stakeholders are aware of those risks—can help make a solution more secure.

- Get to know your data: The quantity and variety of data collected via IoT—and the fact that so much of that data is now held by third parties—can make it difficult for companies to know if their data has been breached. When dealing with tremendous volumes of IoT data, small, virtually unnoticeable thefts can add up over time. Companies can address this threat by developing a deep understanding of the data they possess and combining this knowledge with analytics to measure against a set “normal.” By establishing a baseline of access and usage, IT leaders can more readily and reliably identify possible abnormalities to investigate further.

Where do you start?

As IoT gains momentum, many organizations find themselves paralyzed by the sheer volume of vendor promises, the number of novelty examples being imported from the consumer realm, and by an overarching conviction that something real and important—yet frustratingly out of focus—is waiting to be tapped into.

To maximize value, reduce risk, and learn fast, those just beginning their IoT journey should follow three innovation principles: “Think big, start small, scale fast”:

Think big

- Ideate: Analyze the big ideas and use cases in your industry. Move beyond sensing to doing. Also, explore opportunities for achieving greater consumer and human impact with IoT.

Start small

- Take stock: Before investing in new equipment, conduct an inventory of all the sensors and connected devices already on your balance sheet. Find your brownfields. How many sit dormant—either deactivated or pumping out potentially valuable information into the existential equivalent of /dev/null?

- Get to know the data you already have: Many organizations have troves of raw data they’ve never leveraged. By working with data scientists to analyze these assets before embarking on IoT initiatives, companies can better understand their data’s current value. Likewise, they may also be able to enhance this value by selectively installing sensors to plug data gaps.

- Pilot your ecosystem: Pick proven IoT partners to quickly pilot ideas, try new things, and learn quickly from failures. Many aspects of IoT cannot be tested or proven in laboratories but only with real enterprise users and outside customers.

- Get into the weeds: At some point, IoT initiatives require low-level expertise around the underlying sensors, connectivity, embedded components, and ambient services required to drive orchestration, signal detection, and distributed rules. The difference between a provocative “proof of concept” and a fully baked offering lies in a host of nuanced details: understanding the precision and variability of underlying sensing capabilities; MEMS sourcing, pricing, and installation; and wireless or cellular characteristics, among others. To fill knowledge gaps in the short term, some organizations leverage talent and skill sets from other parts of the IT ecosystem.

Scale fast

- Adopt an agile approach: Go to market and iterate often. One benefit of all the investment being made in and around IoT is that the underlying technology is constantly improving as existing products evolve and new categories emerge. As you explore possible IoT strategies and use cases, consider using lightweight prototypes and rapid experimentation. This way, you can factor in feasibility concerns, but you won’t be saddled—at least for the time being—with the burden of “enterprise” constraints. As compelling ideas gain momentum, you can then shape your solution, refine the business case for it, and explore it at scale.

- Enhance your talent model: Just as aircraft manufacturers hire aeronautical engineers to design products and software vendors employ legions of coders with specific skills, so too must companies pursuing IoT strategies hire the right people for the job. Does your IT organization currently include talent with the hardware expertise needed to operate and maintain thousands of connected devices? Most don’t. Before pursuing an IoT strategy, consider enhancing your talent model not only to bring in new skills from the outside, but also to reskill current employees.

- Bring it home: Remotely deployed assets and equipment often have starring roles in IoT use cases. But call centers, manufacturing floors, and corporate offices also offer considerable IoT potential. Consider how creating an “intranet of things” might lead to improved workplace conditions and enhanced comfort and safety at individual work stations. Moreover, how might reimagining employee experiences in this way help your company attract new employees and retain existing ones?

Bottom line

The Internet of Things holds profound potential. It is a futuristic fantasy made real—the connected home, connected workplace, and connected government come to life. The sheer scope of IoT carries countless implications for business, both finite and abstract. To sidestep such distractions, focus on solving real business problems by creating bounded business scenarios with deliberate, measurable value. For example, how can you use IoT to get closer to customers or increase efficiency in your manufacturing operations or supply chain? Look for hidden value in your brownfields. Move from strategy to prototyping as quickly as possible. Only real data, actual users, and sensors that respond with actions can demonstrate the remarkable value proposition of IoT.

Deloitte Consulting LLP’s Technology Consulting practice is dedicated to helping our clients build tomorrow by solving today’s complex business problems involving strategy, procurement, design, delivery, and assurance of technology solutions. Our service areas include analytics and information management, delivery, cyber risk services, and technical strategy and architecture, as well as the spectrum of digital strategy, design, and development services offered by Deloitte Digital. Learn more about our Technology Consulting practice on www.deloitte.com.