Rethinking human services delivery has been saved

Rethinking human services delivery Using data-driven insights for transformational outcomes

19 September 2015

Thanks to advances in technology and analytical techniques, human services agencies now are poised to move beyond transactional service delivery.

Introduction

Dr. Jeffrey Brenner’s patient’s blood pressure and diabetes were so out of control that, at just 39 years old, the man was going blind and suffering from kidney disease. If the patient had presented at another hospital, as he had on numerous prior occasions, doctors might have noted the patient’s moderate developmental deficits, adjusted his insulin dose and blood pressure medicine, and sent him on his way.

Rather than simply treat the immediate symptoms, Dr. Brenner’s staff opted to pay a visit to the patient’s home, where they found that the patient lived in unsafe conditions with his mother and was not keeping up with his medications. Their living conditions were so chaotic that there was little chance his condition would improve without intervention.

A program-centric view often misses important information about the actual lives of individuals and families, and can prevent them from getting the support they need to improve the trajectory of their lives.

The intervention he needed, it turned out, was supervised housing. New living arrangements allowed him to get help taking his medications on time, which in turn made it possible to avert dialysis for a while—and save the tens of thousands of dollars it costs.1

The intervention he needed, it turned out, was supervised housing. New living arrangements allowed him to get help taking his medications on time, which in turn made it possible to avert dialysis for a while—and save the tens of thousands of dollars it costs.1

The story of Dr. Brenner’s patient highlights a fundamental aspect of society’s safety net: Health and human services agencies, by design, take a program-centric view of the world and are often more transactional in nature than they are transformational. Rather than identifying and addressing the problems that bring individuals and families into contact with the social safety net, human services programs instead tend to see people through the lens of eligibility: The client is enrolled in the programs for which he is eligible, which means there is a particular set of services he can receive, even if those might not be the ones he really needs to improve his situation. This program-centric view is a lingering byproduct of the way health and human services programs were originally created—as stand-alone programs rather than as an integrated safety net.

But this program-centric view often misses important information about the actual lives of individuals and families, and can prevent them from getting the support they need to improve the trajectory of their lives.

Today’s human services programs tend to be focused on administering the individual programs and services that fall under their purview, rather than the ultimate outcomes those programs and services are meant to produce.

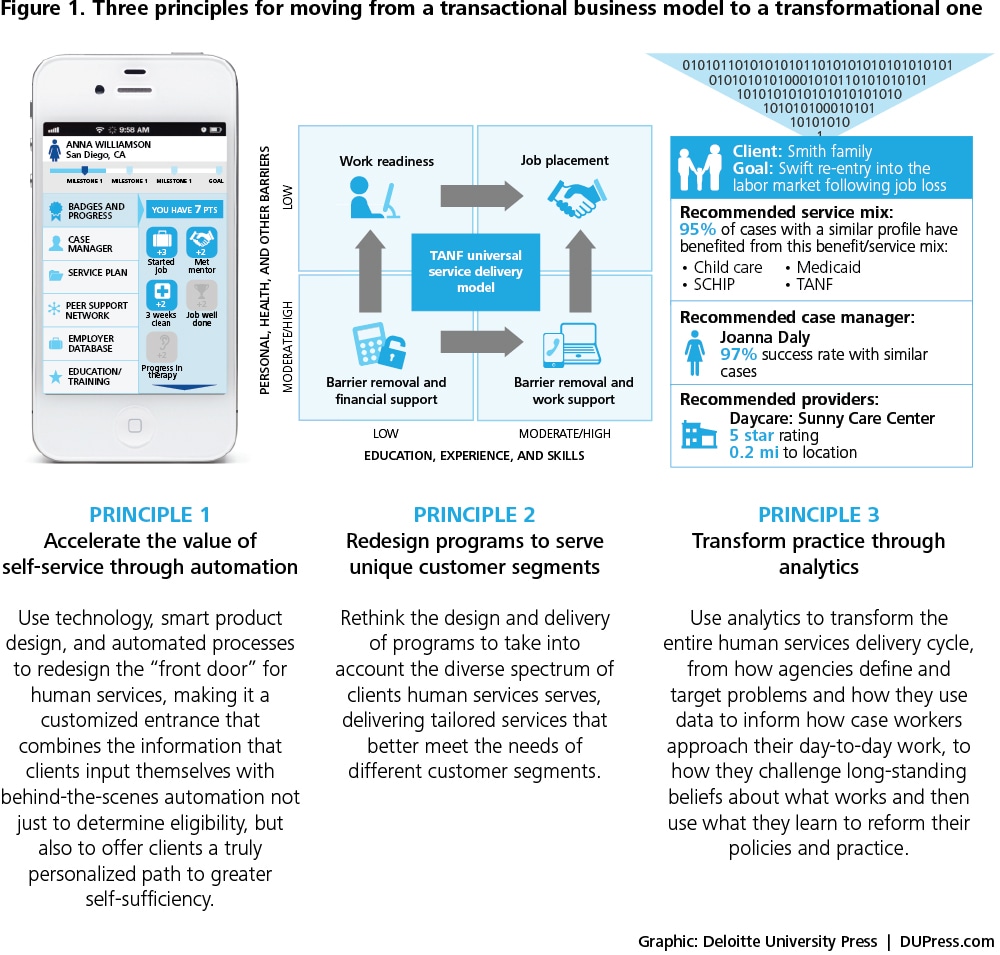

This report lays out three principles human services agencies can adopt to help change a transactional business model into one focused on transformational outcomes (see figure 1).

Moving from transactional service delivery to transformation

Although its core mission is to improve the trajectory of people’s lives, human services has long been more transactional than transformational.

For most human services programs, the business day consists of programmed actions and reactions, inputs and outputs, moving back and forth among government workers, their data systems, and their clients. Success is defined primarily by the timeliness and accuracy of these transactions rather than their results. This has led to a model in which “outcomes” are in fact merely outputs: Did we issue food stamps in a timely fashion? Did we approve 98 percent of our Medicaid applications within 30 days? Did we respond to 95 percent of our hotline calls within 24 hours?

But such measures do not necessarily translate into meaningful outcomes for real people. As former Arizona Department of Economic Security Director Clarence Carter observes, “There must be an objective beyond simple coordination and the receipt of benefits.”2

What’s often missing, particularly in eligibility programs, is any consideration of the extent to which these quantitative transactions have anything to do with qualitative changes in people’s lives. If an agency responds to 98 percent of its child-abuse hotline calls within 24 hours, what about the 2 percent the agency didn’t get to—were those children safe? And what percentage of calls to which the agency responded were eventually “screened out,” found to be based on unfounded allegations?

Or, more simply: To what extent are human services agencies doing the right work, for the right people at the right time, and thus achieving meaningful results?

This is not to say, of course, that output measures are irrelevant. They do matter and human services agencies should continue to track them. There will always be a needy individual or family that depends on timely and accurate delivery of programs and services. And there is certainly no shortage of federal and state reporting requirements and guidelines dictating how agencies should capture and publish their results.

The ability to turn volumes of data into actionable insights opens up new possibilities for redefining human services—for moving beyond a strictly transactional business model to one that is also transformational.

But transactional measures alone cannot support the kind of outcomes for which human services systems were created. And yet it’s easy to become fixated on transactional measures because they are exactly the requirements for which agencies are likely to be held publicly accountable. As a result, the people who work in internal data reporting are driven largely by the capture and reporting of performance indicators that may have little or no relation to real-world results for clients.

In this environment, it’s entirely possible for an agency to meet or exceed transactional performance metrics while experiencing breakdowns in the system—whether it’s food stamps ending up in the wrong hands, millions of Medicaid dollars channeled to one doctor at multiple addresses, or a child who is seriously injured despite multiple visits by a child welfare agency. And when human service systems experience their worst failures, where it matters the most, it often becomes obvious that traditional performance indicators do not guarantee meaningful, mission-critical outcomes for the people who rely on these services.

But this all-too-common pattern is beginning to change, thanks to the rapid proliferation of new technologies and methods, and the introduction of more sophisticated data analytics.

While human services agencies have always collected, stored, and reported a glut of data, the information rarely was readily available for problem-solving or managing day-to-day work. With today’s nimble and relatively inexpensive tools for data management and manipulation, however, information and insights that once might have taken a roomful of analysts weeks to understand can be put in front of workers and clients in near-real time.

This ability to turn volumes of data into actionable insights opens up new possibilities for redefining human services—for moving beyond a strictly transactional business model to one that is also transformational.

What might this look like, using transactional data to track people-centric outcomes?

What if we could know more about the people served and how the human services workforce serves them—and therefore, more about the potential impact of an agency’s work on their lives and their future? What if we could know more about each child’s day-to-day risk for maltreatment? What if we could get real-time reports that prompt us to take a second look at a particular case? What if we could see which doctors’ and clinics’ billing practices seem disproportionately higher than others similarly situated? What if we could see which kinds of food stamp cases are more prone to error, and had a chance to double-check our work on those cases?

What if we could predict which families are more likely to achieve financial independence if a single factor in their lives changes, and predict those factors based on something in a case file or external data about similarly situated families? And what if we could do all this while we’re determining their eligibility, so we would know which services are most likely to help them move forward?

These kinds of insights could help elevate human services from the realm of transactional service delivery, allowing agencies to measure the actual impact human services have on the lives of those they serve.

We begin with a look at how human services can automate its transactional business functions.

Principle 1: Accelerate the value of self-service through automation

Caseworkers are the front line, the people best situated to improve the trajectory of clients’ lives. Too often, however, they are shackled by paperwork and kept from the hands-on work that actually transforms lives.

Today, we can change this pattern. Thanks to technological advances, we can work to eliminate the paperwork burden and provide case management that is intensive, specialized, and reserved for the clients who need it.

Redesigning the front door

Human services agencies should ask themselves how they can use technology, smart product design, and automated processes to redesign their “front door,” making it a customized entrance that combines the information that clients input themselves with behind-the-scenes automation, not just to determine eligibility, but also to offer clients a personalized path to greater self-sufficiency, one that clients can self-navigate and manage on their own behalf.

Of course, some clients—those with mental illness, developmental disabilities, chronic substance abusers, the chronically homeless—may not be able to get back on their feet without more extensive help. But that’s an argument for engaging clients with less complex cases in their own service delivery, freeing caseworkers to focus their attention on those with more critical needs.

Today, citizen portals provide an online front door to many health and human services programs, allowing people to apply for benefits, check benefit status, file changes, renew benefits, and upload documents to case workers, all without an office visit.

While clients have benefited from this convenience, however, self-service portals have not necessarily produced meaningful savings in caseworker time.

“No-touch” and “low-touch” eligibility solutions

But with the implementation of the Affordable Care Act’s technology requirements, this is beginning to change.

Regulations established by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) have long required states to establish timeliness and performance standards for determining eligibility. What’s new is the growing technical ability to process the majority of health care applications with reduced or no human involvement. Automating manual worker functions can help states to keep up with the increasing volume of health care and SNAP (Supplemental Nutritional Assistance Program) applications.

Automating eligibility determinations

Many states are pursuing “no-touch” eligibility systems that automate the processing of medical assistance applications that are eligible for modified adjusted gross income (MAGI)-based processing with little or no caseworker intervention. Taking advantage of data exchanges and real-time verifications, applications and redeterminations can lead to “real-time” eligibility determination for MAGI-based Medicaid.

In the past, health care applicants had to wait days or weeks for an eligibility determination; with no-touch eligibility, they can receive an answer immediately upon submitting an application. Benefits can be issued sooner as well. And caseworkers can spend less time on data entry and more on clients.

Increasing the value of low-touch and no-touch systems

As no-touch eligibility systems expand to other means-based programs, human services agencies will benefit from additional time savings accruing from automated application processing and other time-consuming tasks such as processing renewals and re-verifications—time that can be redirected to more transformational work.

Furthermore, it is quite possible to push the capabilities of these no-touch solutions so they eventually facilitate seamless service referrals, enhancing the ability of human services clients to self-navigate programs and services. For those applying for economic assistance, for example, a check for the right amount at the right time is simply a successful government transaction. But automatically connecting the applicant with the state’s full spectrum of employment services to find a job that suits their interests and skills represents a transformational outcome, for them, their families, and the government systems serving them.

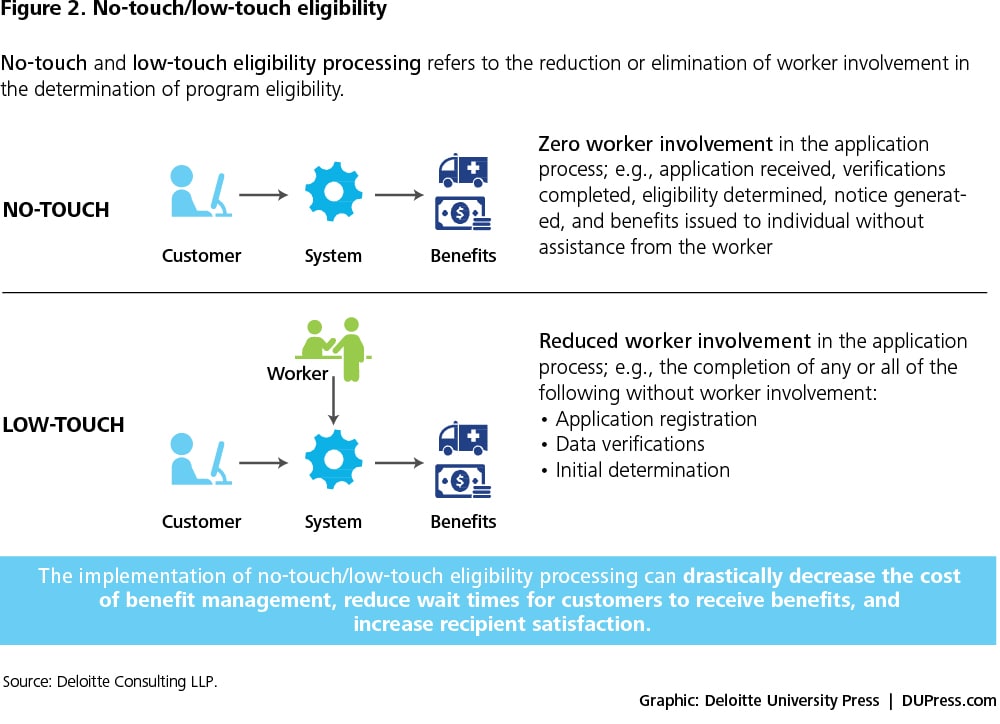

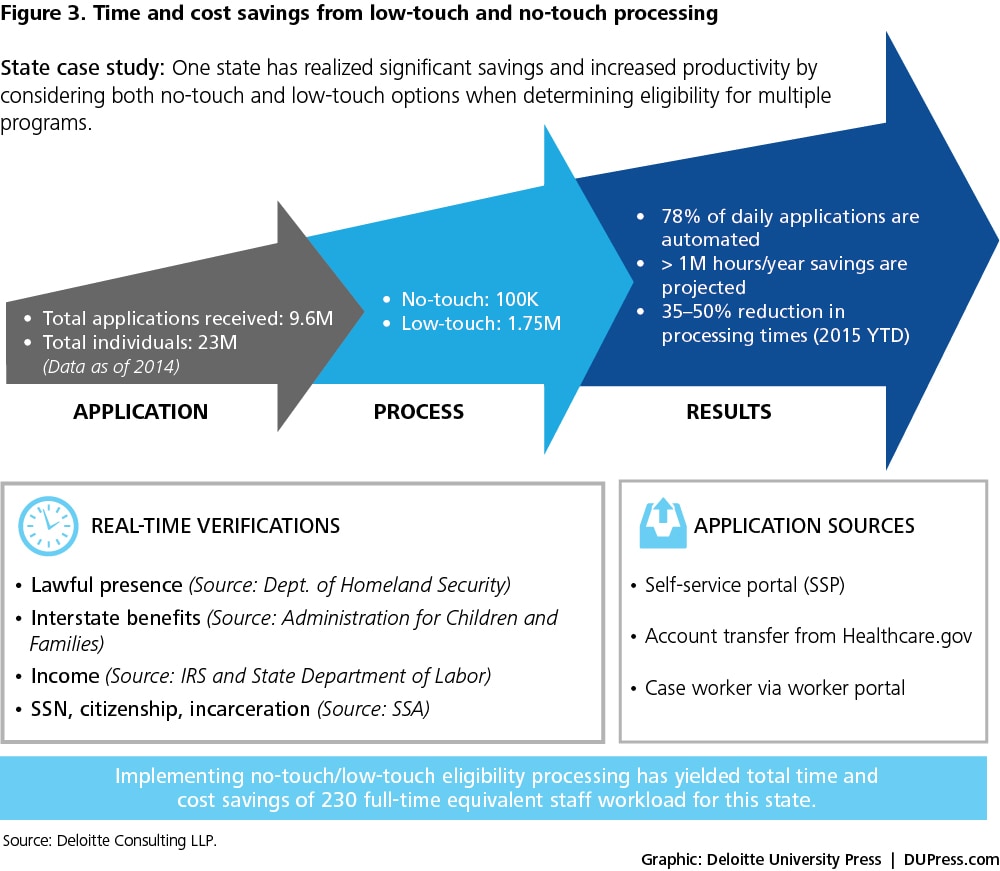

This said, it’s not possible yet to push all—or often even the majority—of applicants through no-touch solutions unless a state is willing to accept at face value everything an applicant says as being true and correct, which would likely increase error rates. Adding other Medicaid programs makes preventing error even more of a problem and adding human services programs even more so. That’s why it’s necessary to think about this issue in terms of “no-touch” and “low-touch” application processing. Significant time savings can still accrue with low-touch eligibility, which entails reduced worker involvement in the application process (see figure 2).

The implementation of no-touch/low-touch eligibility processing can sharply reduce the cost of benefit management (see figure 3), cut wait times for customers to receive benefits, and increase recipient satisfaction. Moreover, as low-touch and no-touch solutions continue to evolve, caseworkers can shift their focus from transactional services to life-changing work that benefits clients with complex needs.

Principle 2: Redesign programs to serve unique customer segments

Emergency-room doctors figured it out a long time ago. The triage protocol is designed to assess patients based on the severity of their immediate conditions and treat them accordingly.

Human services agencies do things differently. Rather than probing the circumstances that bring individuals and families into the safety net, and targeting the problems that must be solved to get them back on their feet, case managers tend to focus on identifying which programs the individual or family is eligible for—irrespective of whether those programs align with the reasons they came into contact with the safety net or the activities that are most likely to enable them to “bounce off the safety net” and leave successfully.

This culture of eligibility pervades human services, offering packages of services and benefits that may over-treat—or entirely miss—the problems that bring clients into the safety net in the first place. This approach is expensive and often fosters dependency, since individuals may face an abrupt loss of benefits if they leave the system for full-time employment.

An individual starting a job, for example, may lose all cash assistance just as childcare, transportation, and medical costs increase dramatically, resulting in a lower total household income than the benefits previously received. This “benefits cliff” promotes long-term dependency and can trap people in the safety net rather than helping them find their way out of it.

The challenge, then, is to understand which goals are best for each individual or family, and to provide them with the services and benefits most likely to help achieve them.

One size fits few: Customer segmentation

In the commercial world, businesses do this by breaking their larger customer population into sub-groups with similar characteristics. Doing so allows them to tailor their services to the unique needs of each customer segment more efficiently and effectively. An office supply store, for instance, might work quite differently with a Fortune 500 company that orders in bulk than it does with students who want to buy a stapler in a new and popular color.

A one-size-fits-all model is poorly suited for the diverse needs of human services clients. The needs of clients are not all equal. This recognition is giving rise to a new wave of experimentation, rooted in the premise that customized program design and delivery, based on a deeper understanding of the client, can lead to better outcomes.

Today, we can rethink the design and delivery of human services to take into account the diverse spectrum of clients, delivering tailored services that better meet the needs of different customer segments. The overarching goal is to get more individuals and families out of the system—not by redefining eligibility or cutting services, but by applying the right mix of services and benefits to help them achieve self-sufficiency, or to improve the trajectory of their lives in cases where self-sufficiency is not an attainable outcome.

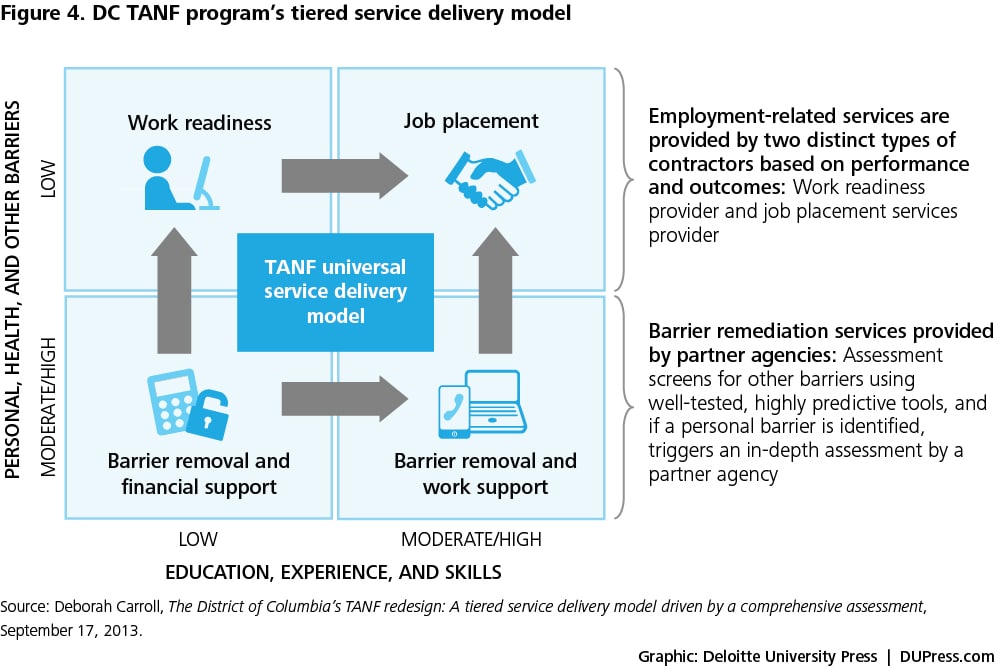

Washington DC’s tiered service model

One of the most far-reaching efforts to segment the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) client base is taking place in Washington DC, where the Department of Human Services’ Economic Security Administration is overhauling its TANF program.

With one of the nation’s highest shares of TANF recipients, many of the District’s participants languished on the rolls for years. “We knew that there were a group of families that had no work participation and we were trying to understand what would motivate them to gain work and what they would find engaging and worth their time,” says Deborah Carroll, director of the DC Department of Employment Services and former administrator for its Department of Human Services Economic Security Administration.3

Redesigning DC’s TANF program

In 2011, the District piloted a redesigned program to customize TANF service delivery based on its assessment of specific client needs. This assessment includes an analysis of strengths and weaknesses, considering everything from family and work histories and individual interests to problems such as substance abuse or mental health issues.4 The assessment is “solution-focused” and designed to solicit information about what has and hasn’t worked in the past. Typical questions include:

- How did you get by every day leading up to today? What changed that brought you here?

- With the problems you face, how do you manage to get through every day?

- What have you tried to address your problems? What worked and what didn‘t?

- What if a miracle occurred and all of your problems went away—what would your life look like?5

The result of the assessment is a customized profile that helps the agency categorize the client into one of the following four segments offering a specific suite of services (see figure 4):

- Job placement (rapid employment for those who are work-ready)

- Work readiness (skills training for those with low barriers and low skills)

- Barrier removal and work support (higher barriers but higher skills)

- Barrier removal and financial support (high barriers and low skills)6

This assessment drives the individual responsibility plan, a contract negotiated with the client, as well as the service referrals the customer receives. If personal barriers are identified, clients are referred to partner agencies for subsequent in-depth evaluations (for mental health issues, substance abuse, etc.).

According to Carroll, “This approach requires a renewed emphasis on helping families and individuals climb out of poverty, not just administering a benefits program.”7

Rather than just “doing things right”—securing the right verification documents and disbursing benefits in a timely fashion—the redesign has shifted the agency’s focus to “doing the right thing.” Questions such as “What brought the family in here?,” “What could be done to fix that?,” and “How can we have the biggest impact on this situation?” serve to drive the outcome the agency is seeking: moving TANF customers toward greater levels of self-sufficiency by helping them prepare for, find, and keep unsubsidized employment that provides a livable income.8

While the full rollout of the redesigned program is still in its early days, an evaluation of the initial pilot showed a tenfold increase in work activity among TANF recipients. According to Ed Lazare, executive director of the DC Fiscal Policy Institute, the results suggest that “the low rate of participation in TANF employment activities in recent years largely reflects the fact that TANF services were not well targeted to the individual needs of families.”9

Using customer segmentation to integrate service delivery for high-touch clients

The state of Washington also uses client data to better understand the various populations it serves, and to craft new approaches that can improve outcomes for certain client segments.

The state’s Department of Social and Health Services (DSHS) has, for instance, learned that 43 percent of its service dollars go to 11 percent of its clients who use services from three or more program areas.10 These high-cost users often have complex, interrelated issues that may include health conditions, family problems, behavioral health needs, criminal records, and other employment barriers. According to DSHS, “Integrated service delivery for these clients results in better outcomes through coordinated case management, fewer points of entry for clients, fewer barriers to care, slower disability progression, less emergency and crisis care, reduced inpatient and institutional care, and lowered costs.”11

By integrating service delivery around “high-touch” customers who can benefit the most from greater coordination of care, human services agencies can channel scarce resources where they’re needed most.

Applying customer segmentation to human services

Human services administrators can use customer segmentation to develop targeted initiatives that take into account the distinct attributes of different customer groups they serve. Through segmentation, the unique needs of each sub-group can be identified and translated into services designed to benefit both customers and taxpayers.

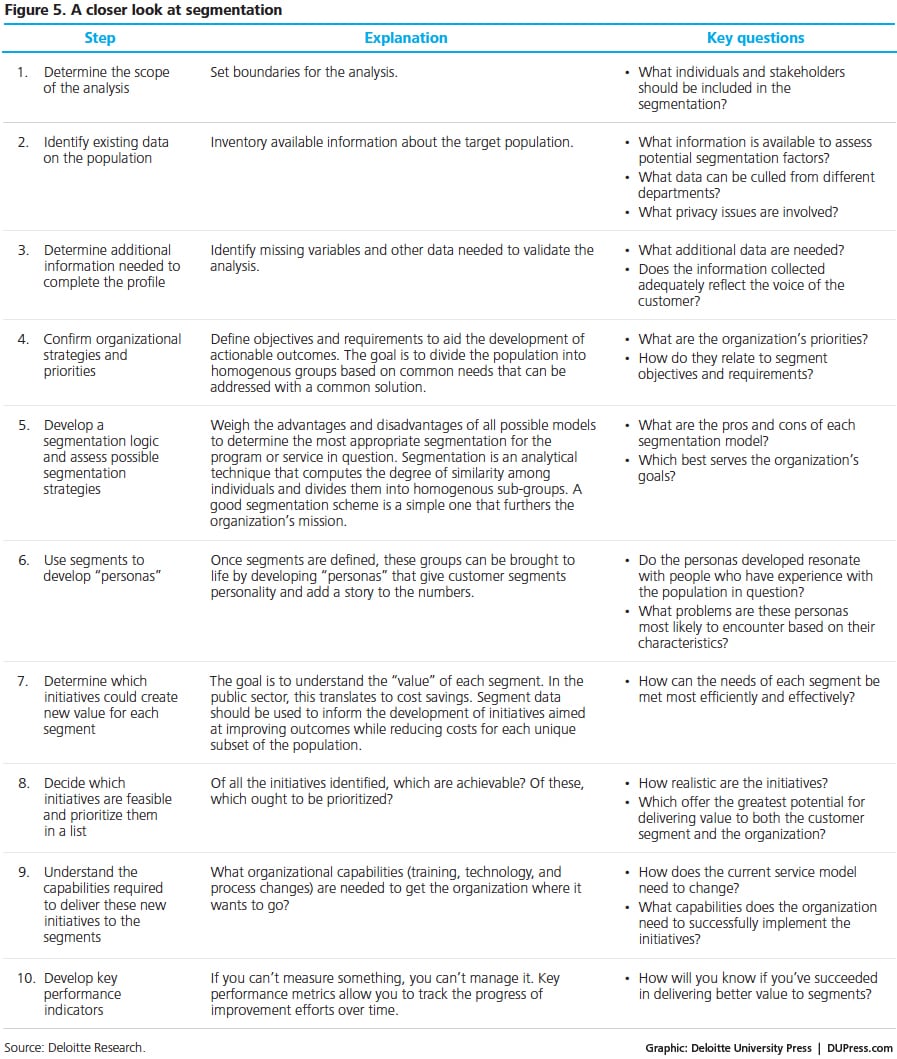

Segmentation is more art than science—not a one-off event but a continuing exercise, performed at regular intervals to keep pace with changing customer populations and evolving needs and preferences. The general process can be broken into 10 steps (see figure 5).

Principle 3: Transform practice through analytics

Thanks to advancements in technology, enhanced data capture, increased use of advanced analytics, and a shift in focus from “hindsight” indicators to predictive factors, human services agencies can glean new insights from transactional data and use them to fundamentally transform the relationships between workers and their tasks, between workers and their clients, and between clients and the services they receive.

Analytics holds the potential for transforming the entire human services delivery cycle, from how human services agencies define and target problems, to how they use data to inform how case workers approach their day-to-day work, to how they challenge long-standing beliefs about what works and then use what they learn to reform their policies and practices.

“Hot spotting”: Using geospatial data to see problems in a new way

When existing government data is coupled with location data, the resulting maps can provide a powerful window into complex public policy problems.

Take, for example, Harvard economists Raj Chetty and Nathaniel Hendren’s recent study of the effect of place on intergenerational mobility. Using earnings records to track the careers and neighborhoods of millions of families with children that moved during a 17-year period, Chetty and Hendren found that the neighborhoods in which kids grow up play a critical role in shaping their opportunity for success later in life.12 Among the 100 largest jurisdictions across the United States, children who grow up in Baltimore, for example, face worse odds of escaping poverty than those that grow up in San Francisco.13

When existing government data is coupled with location data, the resulting maps can provide a powerful window into complex public policy problems.

Chetty and Hendren are not the first to use the power of geospatial analysis. Medical “hot spotting” is often used to identify a relatively small number of patients, often in the same geographic locations, that account for a disproportionate share of health care spending. In Camden, New Jersey, for example, residents in just two buildings accounted for nearly $30 million in services. By better coordinating these clients’ health care and addressing their social circumstances, the Camden Coalition of Healthcare Providers was able to cut these costs by more than half.14

Target interventions to neighborhoods

The concept is gaining steam in the human services field as well. For more than a decade, New York City’s Justice Mapping Center has tracked the residential addresses of inmates in various prison systems—the address they gave when they went into prison. The center found that offenders often are concentrated in particular census blocks, some of them costing state and local governments more than $1 million a year in incarceration costs alone.15 Such findings are spurring some cities around the nation to design re-entry initiatives for specific neighborhoods, with services such as transitional housing and job training for ex-offenders.

Andrew Barclay’s organization, Fostering Court Improvement, uses state and local data to map hot spots of child abuse and neglect—neighborhoods where instances of child mistreatment are especially common.16 This information can help child welfare workers, judges, and others to ask meaningful questions about factors that may be driving higher rates of abuse, and to focus their resources on the neighborhoods—or even particular housing developments—where they’re needed most.

Thinking geospatially can offer significant benefits to human services providers, providing greater insight into client challenges and motivations, and enabling more sophisticated approaches to help them.

Isabel Blanco, former deputy director of South Carolina’s Department of Social Services and now with Casey Family Programs, argues that data from EBT cards, for instance, can help human services agencies understand their customers better:

We should be capturing data on how lower-income people spend their money, because that speaks to their motivations. We should be more like businesses—businesses don’t care about how much I get paid. They care more about our spending patterns and what we choose to spend money on. Could we take data on where EBT dollars are spent, where checks are cashed and so forth, to become the Facebook of networking for the poor, so we can better understand those behaviors?17

When location data is coupled with human services information, every point on the map can provide the perspective needed to better understand the demand for services, and target interventions to improve outcomes and lower costs.

“Metering”: Using data in day-to-day decision-making

Human services executives often find themselves waiting on data. They review reports that describe what happened—but that are too late to change the outcome. As a result, executives often cannot offer their frontline staff the kind of timely information and guidance they need to improve performance. This, in turn, impedes the agency’s collective ability to improve the outcomes it seeks in the lives of those it serves.

Data analytics can offer leaders and managers near real-time feedback and insights to help align the right actions with the right problems and see the impact of that action in time to change course if necessary.

Take child support enforcement, for example.

Advanced analytics in child support enforcement

America’s child support agencies possess a treasure trove of historical data on the cases they manage—case-level information on income, monthly support obligations, employers, assets and arrears, prior enforcement actions taken, and more. Though highly useful, these data often go unused rather than being brought to bear to help caseworkers. As a result, the child support enforcement process generally has been reactive, with noncustodial parents (NCPs) typically contacted only after they fail to meet their support obligations.

Pennsylvania’s Bureau of Child Support Enforcement is an exception to this rule, however. With 15 years of historical data, the bureau used predictive modeling to develop a “payment score calculator” to estimate the likelihood of an NCP beginning to pay court-mandated child support; of becoming in arrears at some point in the future; and of paying 80 percent or more of the accrued amount within three months.18 Based on this score, caseworkers can follow a series of recommended steps to keep a case from becoming delinquent—scheduling a conference, for instance, or telephoning a payment reminder, or linking payers with programs that can help them keep up, such as education, training, or job placement services.

Beyond informing the actions taken in a particular case, analytics also can be brought to bear in management decisions about how casework is prioritized and assigned. More difficult cases can be assigned to caseworkers with more experience or specific skills. Managers can direct workers to focus attention on cases with the most significant potential for collections. And in cases in which the likelihood to pay appears to be very low, caseworkers can intervene early by establishing a non-financial obligation or by modifying the support amount according to state guidelines.

By moving data and information management to the front end of the work so it becomes a day-to-day tool for decision-making rather than a back-end tool for accountability, states are working toward redefining the business model for health and human services.

As a result of its use of data to inform day-to-day practice, Pennsylvania is the only state that meets or exceeds the 80 percent standard set by the federal Office of Child Support Enforcement for all five federal child support enforcement performance metrics.19

Using data to redefine the business model

Other jurisdictions are using advanced analytics to shift practices from reactive to proactive in nature. Washington State, for instance, has developed a web-based analytics tool called the Predictive Risk Intelligence System (PRISM) to support interventions for high-risk Medicaid patients. This tool integrates information from state medical, social service, behavioral health, and long-term care data systems to provide case managers with a risk score identifying the Medicaid clients most likely to need a comprehensive care approach.20 The tool tracks data including demographics, latest medical and dental appointments, hospital stays, health conditions, and prescriptions to paint a detailed picture of each client’s unique circumstances.

Similarly, the Florida Department of Juvenile Justice uses predictive analytics to identify which juvenile offenders are most likely to commit new crimes. The aim is to reduce recidivism by using predictors such as past offense history, home-life environment, gang affiliation, and peer associations to place offenders in specific rehabilitation programs.21

By moving data and information management to the front end of the work so it becomes a day-to-day tool for decision-making rather than a back-end tool for accountability, states are working toward redefining the business model for health and human services. Now they can use data to understand which early interventions make the most difference, and which mix of services could help each client. This, in turn, allows caseworkers to adjust their approaches as circumstances warrant, potentially making the safety net more responsive to client needs and changes in practices over time.

Using data to challenge long-standing beliefs

Policies supported by evidence and firmly grounded in leading practices typically achieve better outcomes. Too often, however, the application of a “cure” is not preceded by a good diagnosis—someone asking thoughtful, probing questions and exploring the data rigorously to gather the right information upfront.

Improving the well-being of children

For years now, child welfare agencies have made strides in identifying abuse and neglect. But simply removing a child from immediate danger is often not enough. Once children are in the foster care system, we need more information about the type of trauma they suffered and the kinds of interventions most likely to help them overcome that trauma and move toward a safe and permanent exit from the system. Therefore, data that help measure risk must be correlated with questions and data that help measure the quality of exits.

The most urgent business questions are often aimed at the front end of the work rather than the back door, which too often assumes that the child’s immediate safety equates with their general well-being. This is in part, however, also why we often see systems struggling with teens involved with the juvenile justice system, or with high re-entry rates for children returned home or placed with relatives or adoptive families. Children living in foster care or in permanent family situations may be safe, but they may still carry with them the trauma that brought them to child welfare in the first place.

To improve children’s overall well-being, agencies should address issues like the trauma of maltreatment that often keeps kids from developing “the skills and capacities they need to be successful in the classroom, in the workplace, in their communities, and in interpersonal relationships.”22 Focusing on children’s well-being means shifting resources from interventions that have proven to have little impact—generic parenting classes, for instance—to interventions that are comprehensive and that work. This means paying attention to such matters as building parents’ ability to sustain their families, and providing children with the kinds of evidence- based interventions that could be effective in helping them recover from the trauma of abuse or neglect. And it means tailoring services to the specific circumstances of each family and each child.

The moral: A transactional system only captures and tracks what is wrong. A transformational system considers the why, and uses information to determine what to do and to track the outcome of that intervention in real time so that it can change course as needed.

In response to the Administration for Children and Families’ focus on promoting child well-being and addressing trauma, a number of child welfare systems are using their Title IV-E waivers to intensify their efforts to transform what happens with children while they are in foster care and to try and strengthen families capabilities to support vulnerable children and keep them out of care.

Checklist for human services administrators: How does your organization stack up?

- Tools: You use data as a day-to-day tool for decision-making rather than just a back-end tool for accountability.

- Assessment: You have a process in place for understanding which goals might work best for an individual or family and you provide them with the services and benefits most likely to help achieve them.

- Segmentation: You can easily identify the customer segments that make up your customer base, as well as their needs and preferences.

- Resources: You understand which customers account for the majority of human services spending.

- Service integration: You integrate service delivery around those with complex needs that could benefit from coordinated care.

- Analytics: You have the analytical capabilities to discern underlying patterns in the data.

- Geospatial analysis: You use location data to better understand the geographic underpinning of complex public policy problems and target resources where they are most needed.

- Planning: You use the data you have to better understand customer needs and anticipate changes in customer behavior that will affect your organization.

- Service: Your organization is pursuing no-touch eligibility solutions and more robust models of self-service that allow clients to self-navigate and manage their own personalized path to greater self-sufficiency, freeing caseworkers up to focus on clients with more critical needs.

- Outcomes: You track and measure not just the timeliness and accuracy of transactions, but also whether your programs are improving people’s lives.

Looking ahead

In the past, when human services executives wanted to drive change, they typically changed the people doing the work or the policies driving their work. Changing their business processes was often the last thing thought of—and for good reason. In government, the business model often is hardwired into and driven by the agency’s technology and data systems.

But if human service agencies have to keep “building to order” every time they need to solve hard problems, we shouldn’t be surprised when the problems don’t go away.

Human services leaders need business models that leverage and integrate the data they have, that are adaptable to rapidly changing technologies, and that use data extraction and analysis to improve frontline practice.

Thanks to advances in technology and analytical techniques, human services agencies now are poised to move beyond transactional service delivery. When agencies can put their data in front of the people, both clients and caseworkers, who need it, in a way they can readily understand, and in time to use the data in a way that affects results, then what was once a transactional business model can become a transformational one, capable of achieving potentially life-changing outcomes in an efficient and cost-effective way.

For more than 45 years, Deloitte state health and human services professionals have worked side by side with state agencies. We are focused on helping agencies improve the efficiency, effectiveness, and accountability of state services and benefits. Our offerings include eligibility and service integration, state health care, child welfare, child care and early learning, and many others. Learn more about our Health and Human Services practice at www.deloitte.com.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.