China's Belt and Road Initiative Recalibration and new opportunities

13 minute read

16 August 2019

China's Belt and Road Initiative is poised to make its mark on Europe. We look at how industry players can benefit from the Initiative's focus on international participation and quality projects.

Executive summary

China’s massive global development project, the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), now includes more than two-thirds of the world’s countries. It has also come a long way from its initial conception as a massive infrastructure project connecting Asia, Europe and Africa. A range of new international opportunities will arise as Beijing works to address these issues.

Our key findings include:

Participation in BRI projects will be more international and inclusive, with greater private-sector involvement. Furthermore, the term “Belt and Road” is no longer synonymous with developing countries, and opportunities will increasingly emerge in more advanced economies, such as Italy.

The focus on quality projects will lead to more transparency and less risks, with a greater emphasis on due diligence. In this regard, international consultancies are well positioned to help their clients assess overseas opportunities and navigate differing regulatory and cultural landscapes.

The range and geographical scope of BRI opportunities will continue to expand, with the fast-growing Digital Silk Road poised to spur several technology-led projects.

Part I. Where does the BRI stand now?

Learn more

Read more about the China-proposed Belt and Road Initiative

Visit the weekly global economic outlook

Explore the economics collection

Download the Deloitte Insights and Dow Jones App

Going more global

China has launched an earnest effort to cultivate greater international participation in funding and developing projects. This, along with Beijing’s focus on quality projects, should broaden access to BRI opportunities and enhance their status.

BRI received a timely credibility boost in March 2019 when Italy became the 130th nation to sign on.1 Although the BRI already counts several less prosperous EU nations among its ranks, Italy is the biggest European economy and first member of the Group of Seven (G7) bloc of advanced countries to join, conferring renewed legitimacy on the Initiative.

Italy no doubt hopes the agreement will lead to more Chinese investment inflows to shore up its aging infrastructure, especially after the collapse of a 50-year-old highway bridge in Genoa in August 2018.2 With Italy’s national debt now at 130 percent of GDP, the BRI is likely seen by members of the country’s newly installed populist ruling coalition as a means of attracting a much-needed infusion of funds.3

Japan is also eyeing BRI opportunities, with speculation it could become the second G7 nation to join. Japanese officials recently announced plans to send a high-level delegation to the second Belt and Road Forum in China in April 2019 to extend their cooperation on BRI-related issues.4

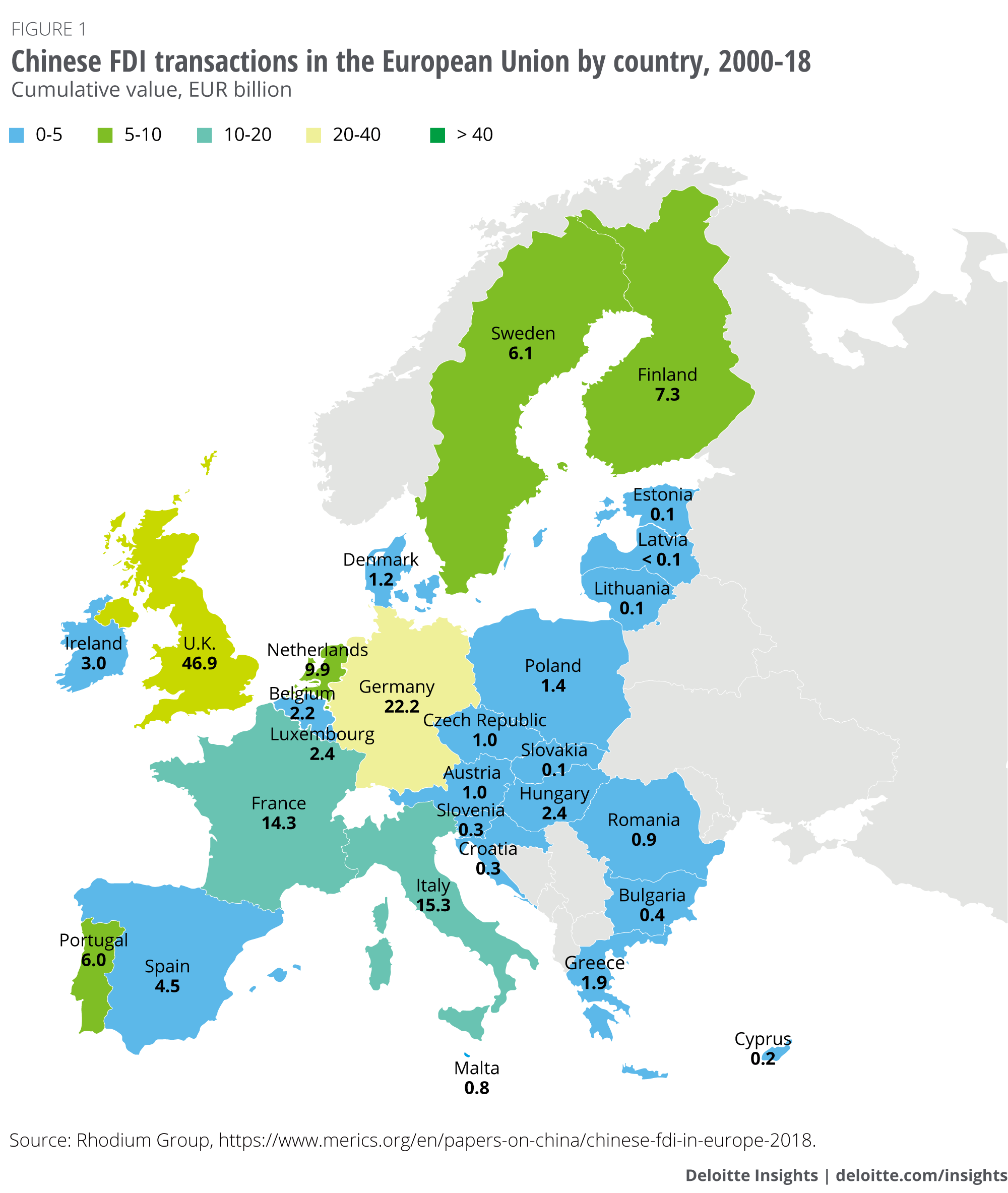

Europe is the leading destination for Chinese investment

Well before the advent of BRI, Chinese investment sought strategic assets overseas, particularly in the advanced economies of Europe.5 Chinese firms have invested heavily in key sectors across Europe over the past decade, with several high-profile acquisitions, including stakes in most of the UK’s leading banks,6 Sweden’s largest carmaker,7 robotics in Germany,8 power utilities in Portugal,9 solar farms in Hungary,10 as well as Greece’s Piraeus port, which has flourished following the investment.11

Italy, meanwhile, is already one of the biggest European destinations for Chinese investment. According to data compiled by the Rhodium Group, since 2000, Chinese enterprises have invested EUR15.3 billion (about RMB115 billion/USD17 billion) in Italian companies in sectors, ranging from luxury brands to high-tech manufacturing and the country’s power grid.12 Since the signing of Italy’s BRI agreement, there have been suggestions it could soon open up its ports to Chinese investment, with Trieste tipped as having the potential to develop into a key gateway to Europe with China’s support.13

Yet Chinese investment going to Europe and North America plunged from 2017 to 2018, declining from USD111 billion to just USD30 billion, according to a report by Baker McKenzie.14

Although Beijing’s capital controls and China’s mounting debt load crimped Chinese foreign investment last year, heightened scrutiny by regulators of Chinese acquisitions—a move that has been criticized as antithetical to free market principles—was a major factor behind the drop in investment, with a large number of deals cancelled or blocked.15

The removal of such protectionist measures is one of the core aims of the BRI. It is therefore imperative that the Initiative extend deeper into the more advanced countries of Europe, as this should reverse the short-lived dip in Chinese investment into the continent,16 especially as Chinese companies tighten their focus on choosing investments more judiciously.

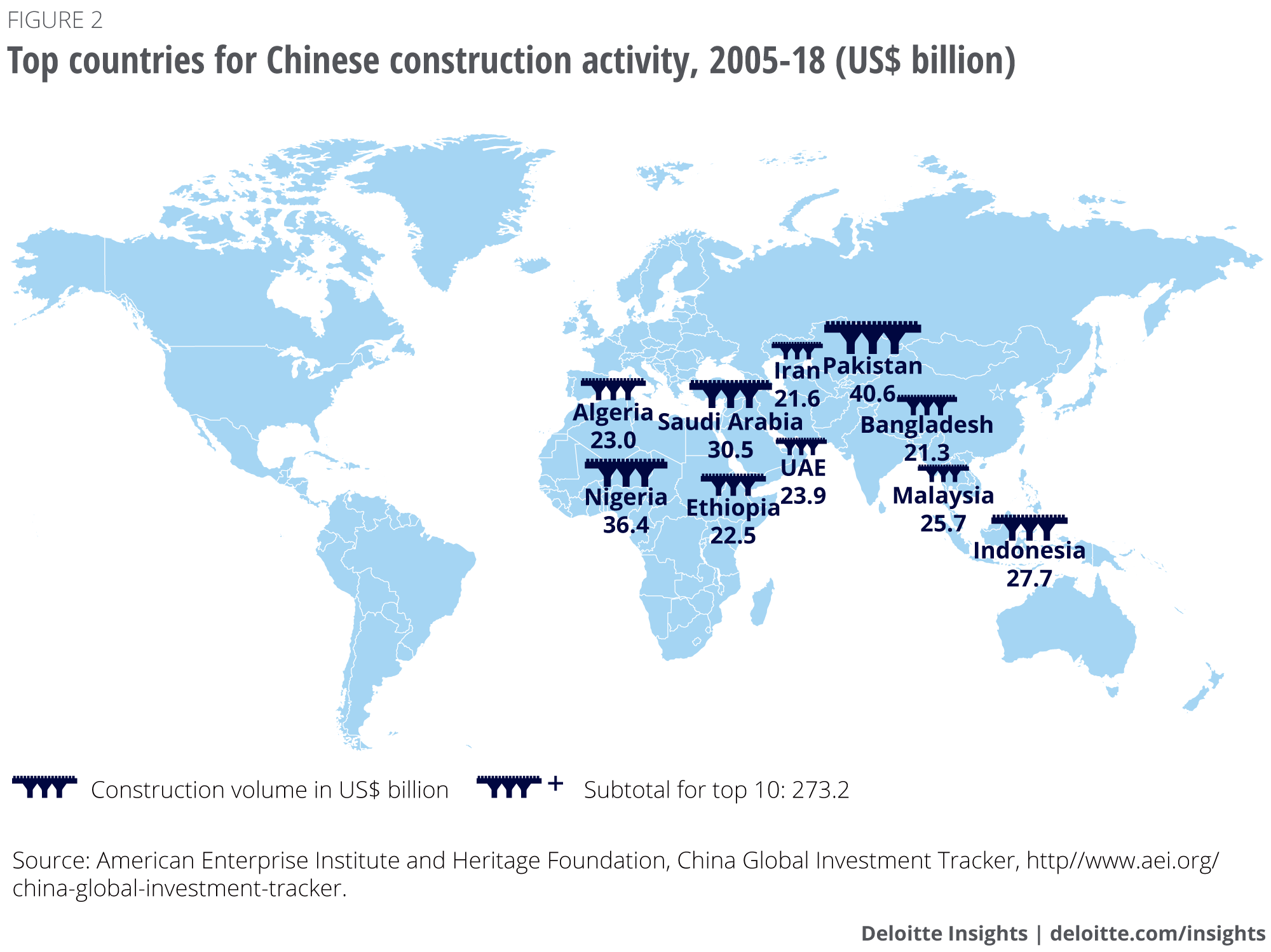

Successes and challenges

The BRI has transformed a substantial portion of the developing world over the past five years. Given the long investment horizon associated with the infrastructure projects of BRI, a commensurate timeframe—10-15 years rather than 3-5 years—should be used when measuring returns. Still, there have been clear short-term benefits associated with construction activity to date, which have boosted the economies of host countries and benefited Chinese and international firms involved in the projects. Larger long-term benefits are in sight, with new infrastructure and improved connectivity likely to facilitate trade and transform the economies of many host countries–by improving continuity. Trade agreements inked under the BRI banner also stand to benefit China and its partners.

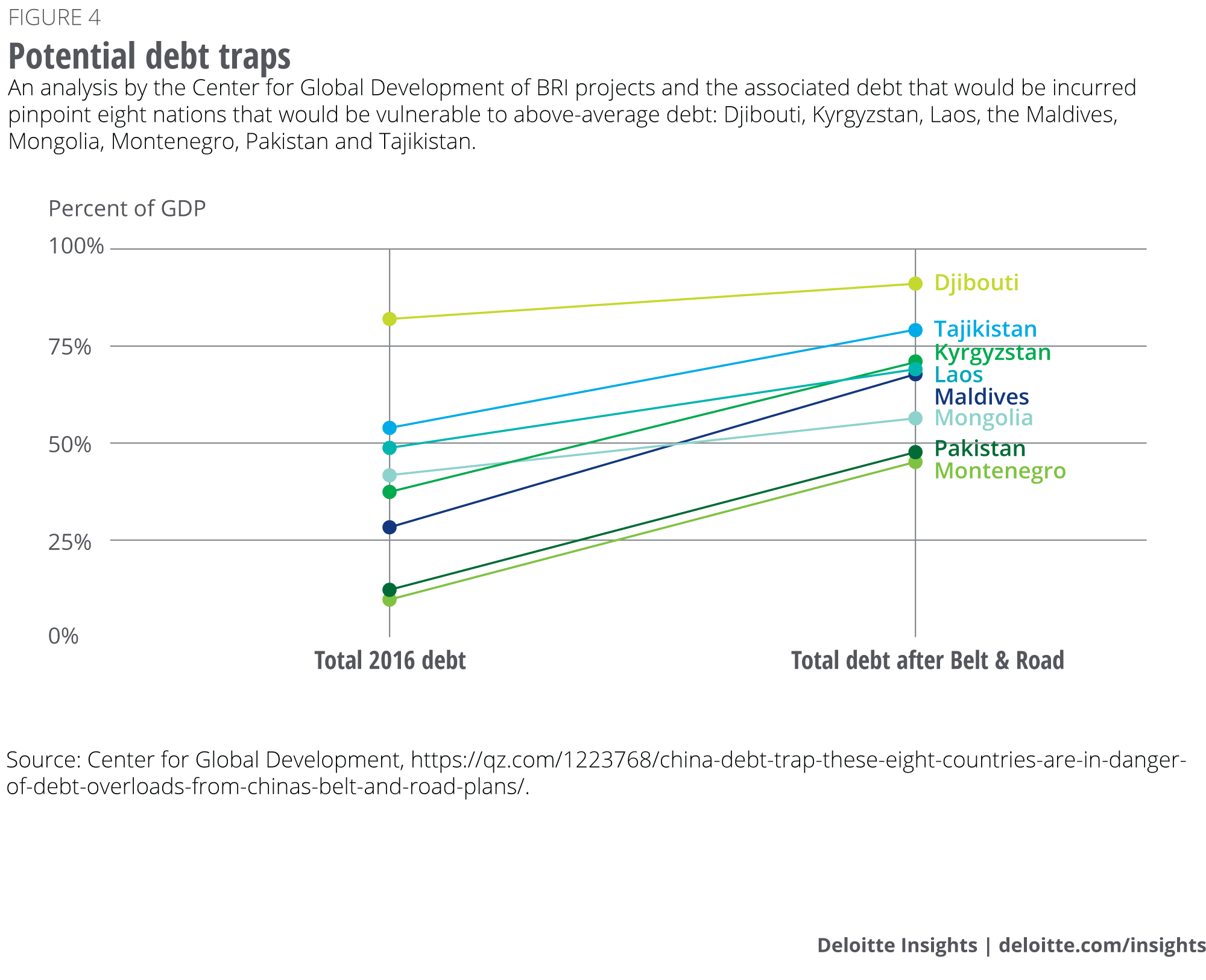

That said, BRI has also faced challenges that have affected the general perception of the Initiative over the past couple of years. The tide of opinion turned sharply toward the end of 2017 when Sri Lanka handed over the strategic port of Hambantota on a 99-year lease to Chinese firms as part of a USD1.1 billion debt repayment deal.17

Elsewhere, governments have been reassessing several BRI projects. In Malaysia, the cost of the BRI’s most expensive undertaking, the East Coast Rail Link (ECRL), was scaled back by a third following negotiations by the country’s new government, led by Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad.18 Projects have also been cancelled or scaled back in Myanmar,19 Pakistan20 and Sierra Leone21 due to concerns about unsustainable debt.

Meanwhile, the new Maldives administration has claimed large-scale graft under the previous government led to the signing of construction contracts perceived to be overly ambitious with Chinese companies and is now seeking a reduction in the debts accrued on those contracts from Beijing.22

Part II. Recalibration in progress

China shifts tack on BRI financing

The backlash to high-profile debt-prompted crises in Sri Lanka, Pakistan and the Maldives has sent a clear signal to China to modify its approach to lending. There is clearly awareness of what went wrong with those projects, such as with the USD4 billion railway linking Addis Ababa with neighboring Djibouti, where the loan repayment terms had to be extended by 20 years.23

At a meeting of Chinese policymakers in January, Han Zheng, the vice‑premier holding the BRI portfolio, reiterated a call for the “high-quality” development of the Initiative. This was preceded last year by the release of guiding opinions by several central government agencies aimed at standardizing funding sources, enhancing general risk-management and better guiding the financing channels for Chinese overseas projects.24

Working with international agencies and multinational corporations (MNCs) is another way for China’s lenders to better assess and hedge financial, sovereign and geopolitical risks.25

The Chinese policy banks funding the BRI, including the China Development Bank (CDB) and the Export-Import Bank of China (Exim Bank) are already pursuing partnerships with international lenders to improve financial governance and manage debt and investment risk.26

Infrastructure gaps can be addressed by making projects “bankable”

The world needs as much as USD3.7 trillion in annual infrastructure spending for years to come, with the potential consequences of failing to close the infrastructure gap more dire in developing countries.27 China’s readiness to extend loans to upgrade roads, railways, ports, and electricity and telecommunications infrastructure is therefore welcome in those countries and the allure of the BRI remains strong, despite mounting concerns about debt sustainability and the commercial rationale of projects.

The Global Infrastructure Forum held in Bali in October 2018 stressed that, contrary to widespread perception, there is enough financing available to fix the world’s infrastructure shortfalls. What is needed is to make the projects “bankable.”28 This needs to happen anyway, because even before China’s policy banks were instructed to step up their due diligence in extending infrastructure loans, the most aggressive estimates of BRI spending fell well short of addressing the anticipated infrastructure shortfall over the coming years.

Paving the way for private investment can be achieved by better assessment of the risks of individual projects and improved project preparation and planning. Concurrently, countries need to step up their procurement processes and regulatory frameworks. The forum also highlighted the vital role multilateral development banks can play in bringing credibility to projects by identifying and removing barriers to private investment, such as weak project preparation, unsupportive policy and regulatory environments and insufficient financial preparation.

China’s focus on the quality and viability of BRI projects should thus help to draw much greater funding from more varied sources, commensurate with realizing its ambitious vision of unfettered global connectivity underpinning a more equitable economic system.

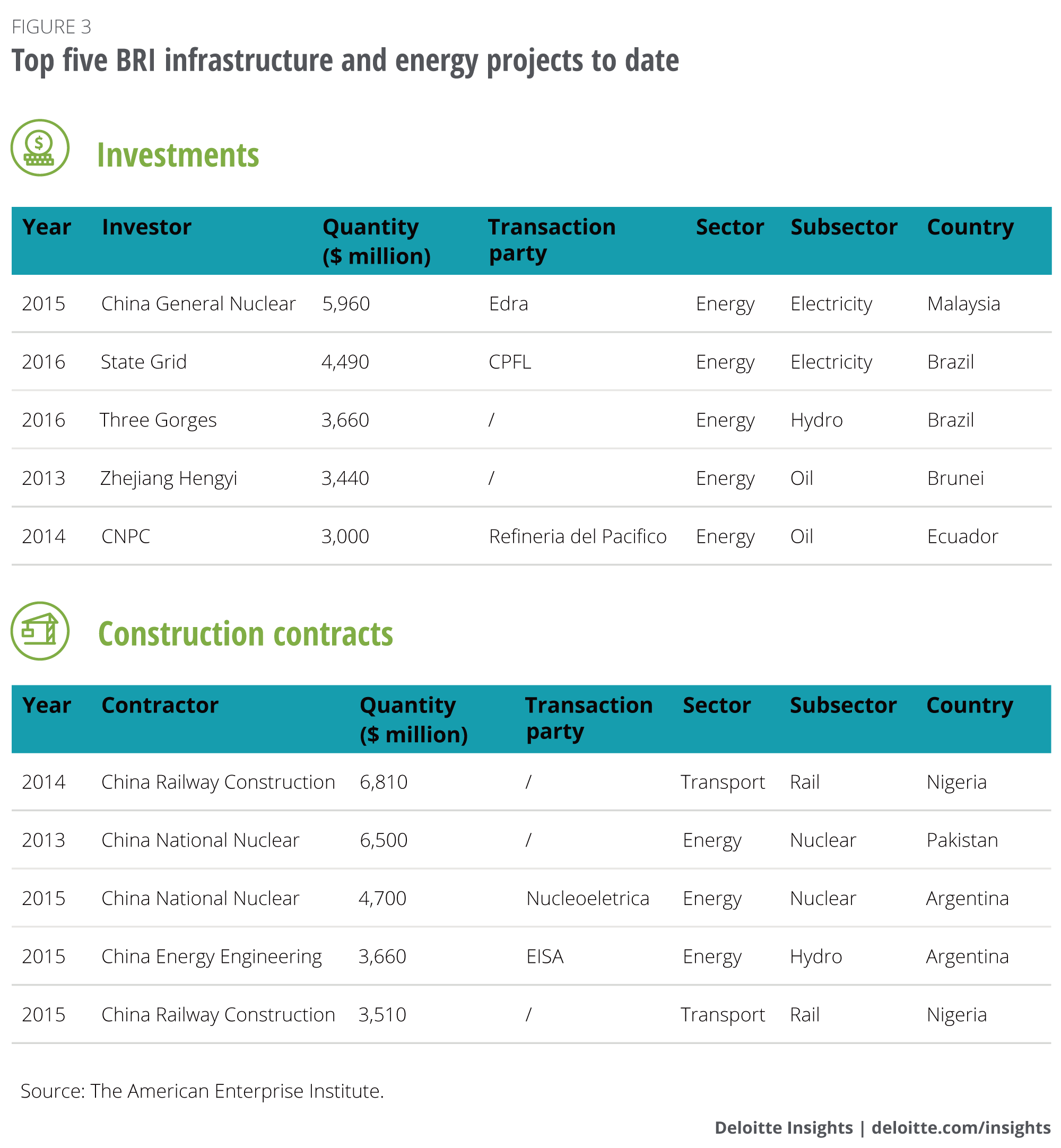

Even before concerns about debt sustainability and project feasibility came to a head, China had sought to foster greater international involvement in financing BRI projects by spearheading the creation of two key multilateral financial institutions: the New Development Bank (NDB) established in July 2015 and funded by the BRICS countries; and the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) set up in January 2016 and cofunded by 57 other countries.29

Among other high-profile international partnerships focused on improving the financing of BRI projects, the People’s Bank of China supported the City of London Corporation in compiling a comprehensive report detailing case studies of BRI projects financed through London by banks such as HSBC and Standard Chartered.

Published in October, this report offers suggestions on how to understand the opportunities and risks of such projects better.30 Standard Chartered provided several insights, having funded more than 50 BRI projects and committed to funding deals worth an additional USD20 billion by 2020. Among the projects already financed by Standard Chartered are a USD515 million power plant in Zambia and a USD200 million electricity plant in Bangladesh, as well as a USD42 million export credit facility for a Sri Lanka gas terminal.

Crucially, the BRI has also prompted the United States to seek to counter China’s rising influence in the Indo-Pacific through measures including a joint investment fund with Japan and Australia to support infrastructure investment that was announced in July 2018, and another alliance formed in April 2019 with Canada and the European Union called the Overseas Private Investment Corporation.31

Handling commercial disputes along the Belt and Road

On 1 July 2018, China formally established two specialized Chinese International Commercial Courts (CICCs) to handle commercial disputes under the BRI. It is envisioned that the CICC in Xian will focus on disputes arising from projects spanning the land-based “belt” of the BRI, while the other CICC in Shenzhen will cover disputes related to infrastructure developments along the maritime “road.”32

Although the formation of the CICCs is viewed as a positive step towards more transparent commercial governance, it is unclear whether they will be sufficient to handle all the disputes that are likely to arise. Furthermore, international investors worried about the independence of courts in China could prefer to seek third-party arbitration in either London, Hong Kong or Singapore.33

Part III. Expanding participation and purview

China has called on US and European MNCs to participate in the BRI, with Zhou Xiaofei, deputy secretary general of the National Development and Reform Commission, saying it hopes to combine its manufacturing and construction expertise with the advanced technology of Western firms to take the Initiative forward.34 Beijing’s push for greater international involvement is also seen as stemming from a desire to counter the perception that the BRI is an attempt to project China’s influence across the world, and to make the Initiative more inclusive.

MNCs are already widely involved in BRI projects. General Electric, for instance, has cooperated with Chinese partners on 37 gigawatts of power generation projects since 2013, providing equipment in countries including Kenya, Pakistan and Saudi Arabia.35

BRI’s five key goals remain the same

With the BRI characterized as a “moving target, loosely defined and ever expanding,”36 it can be difficult to keep track of its evolving nuances and scope. Its key goals, however, remain the same, as we detailed in our comprehensive overview, Embracing the BRI ecosystem in 2018, namely policy coordination, facilities connectivity, unimpeded trade, financial integration and people-to-people bonds.

Also at the heart of BRI is the construction of infrastructure to improve connectivity between Asia, Europe and Africa along two main conduits: the Silk Road Economic Belt of six land corridors and the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road sea route linking the three continents.

Recently, China has strived to emphasize that the connectivity it seeks to engender through the BRI extends beyond transport infrastructure and more generally entails bridging gaps between countries to enable them to interact freely and trade on equal terms.

The Alliance of International Science Organizations in the Belt and Road region was established in 2018, charged with building technology transfer platforms to serve developing countries. To date, China has also built 82 overseas economic cooperation zones in BRI countries with investment of more than USD30 billion. In addition, China is keen to stress its cultural cooperation agreements with BRI members, including the setting up of overseas cultural centers.37

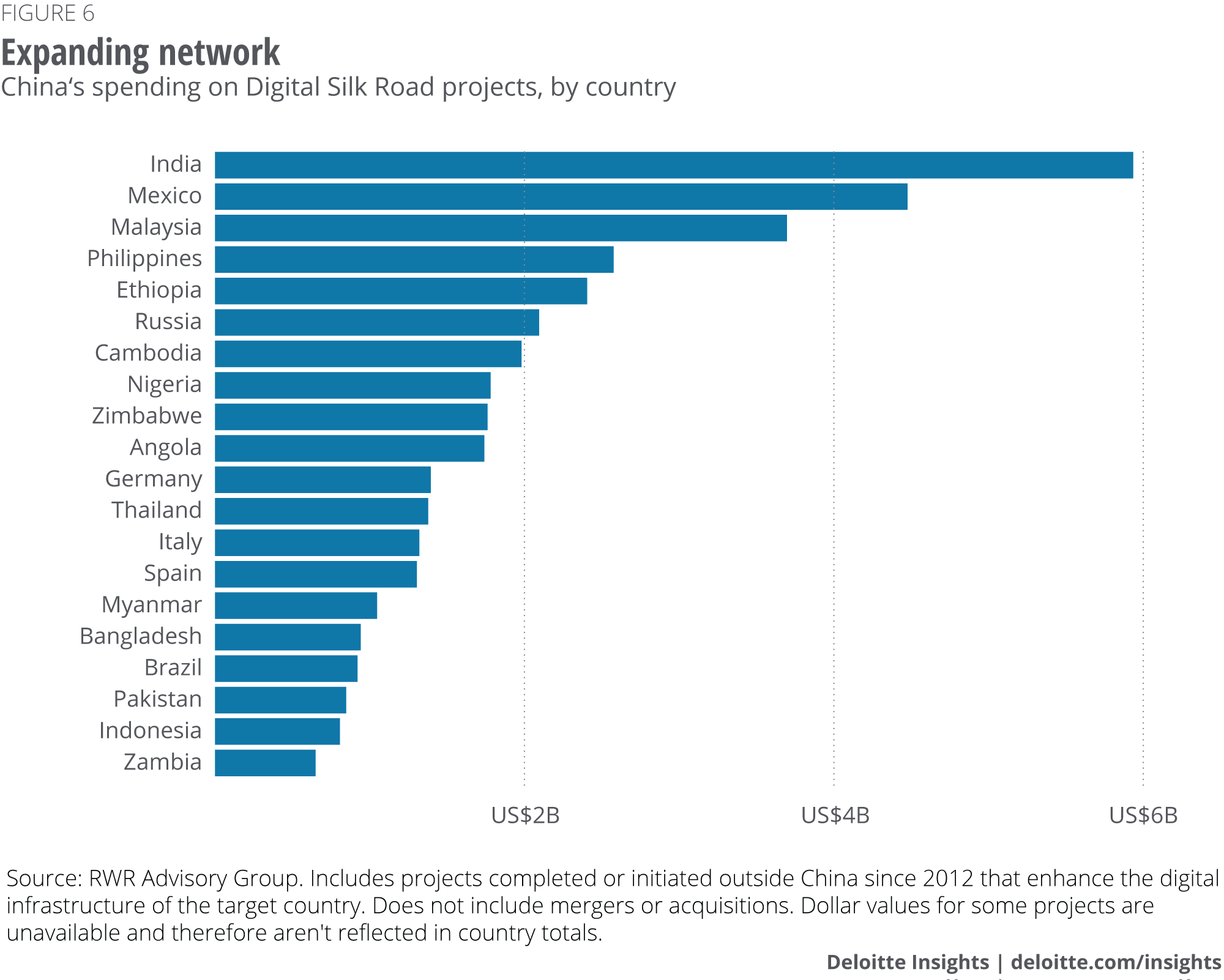

The vast digital dimensions of BRI

In 2018, there was steady progress on the digital components of the BRI, dubbed the “Digital Silk Road,” which currently amounts to an estimated USD79 billion worth of projects around the world, according to RWR Advisory Group, covering optical fiber cables, 5G networks, satellites and devices that connect to these systems.38 The Digital Silk Road is estimated to require total investment of USD200 billion.39

Chinese President Xi Jinping, the architect of the BRI, has said the Digital Silk Road will also encompass quantum computing, nanotechnology, artificial intelligence, big data and cloud storage40—areas in which China is on track to become the world’s leading innovator and filer of patents.41 China’s Vice-minister of Information Technology, Chen Zhaoxiong, last year said China intends to create “a community of common destiny in cyberspace.”

The most tangible infrastructural components of the Digital Silk Road encompass two major undertakings. The first is the upgrading of internet connections across the Belt and Road regions in the form of new undersea cables linking east and west, and rolling out broadband in dozens of countries where such infrastructure is either underdeveloped or non-existent.42

The second component of the Digital Silk Road is a massive expansion of China’s BeiDou navigation satellite network to rival the US-owned Global Positioning System. Some USD25 billion will be spent on expanding the BeiDou network from 17 satellites covering the Far East to 35 covering the entire world. The new satellites were launched last year ahead of schedule and the system is on track for completion by 2020.43

Part IV. Broader cooperation opportunities among companies

Having calibrated BRI and the enormous opportunities it entailed, Deloitte expects broader cooperation among companies. MNCs, privately owned enterprises (POEs) and state-owned enterprises (SOEs) will leverage their respective strengths, deepen their collaboration, boost efficiency in project implementation and aim for higher rate of return, making joint efforts to promote the high-quality development and inclusiveness of the Belt and Road Initiative.

Funding: As discussed earlier, BRI project funding is shifting toward a mix of private capital, multilateral banks and foreign governments. This will offer opportunities to MNCs with expertise in raising funds for large projects.

Deloitte’s research shows more than half of the SOEs know they must boost their ability to attract finance.44 This could see MNCs involved in various ways, from debt or equity financing to M&A, build operate transfer (BOT) contracts, public private partnerships (PPPs) and even engineering, procurement and construction partnerships.

Technology transfer/licensing: Projects in high-technology sectors will bring opportunities, as will those that need to meet high local compliance standards—for instance in the realms of environment, energy-saving technology and health and safety.

In following China’s “Go Global” strategy, its SOEs and POEs are catching up with their Western counterparts in terms of technology, but most still lag behind. MNCs can leverage this, either by collaborating to provide technology or by being acquired.

Quality products: International MNCs have a comparative advantage over Chinese firms in certain areas, placing them in a strong position to offer key middleware or elements of end products to meet the needs in another participant’s global supply chain.

Advanced management experience: Some MNCs have greater expertise in managing infrastructure, real estate and joint ventures, as well as experience in running operations in a range of countries. GE, for example, is on the ground in nearly every BRI country, giving it valuable local knowledge.

Deloitte’s research found that talent is one of the key areas SOEs identify as necessary to boost their chances of success in expanding overseas. Others include improving long-term strategy and better controlling risk.45

Integrated solutions: MNCs can cooperate with Chinese companies in areas that encompass two or more segments. An MNC might provide quality products as well as the related technology and management skills needed to run them.

Conclusion: Three key insights and predictions

The recalibration of BRI and China’s calls for more international participation in the Initiative presents clear opportunities across a range of sectors, from infrastructure and energy to technology and telecommunications. From our experience with BRI projects to date and our analysis of the evolution of the Initiative, we have developed three key insights and predictions for the years ahead:

Although the bulk of BRI projects undertaken to date have been funded and developed by Chinese firms, and SOEs in particular, participation in BRI projects will become more international and inclusive, featuring much greater private-sector involvement. It is also clear that the term “Belt and Road” is no longer synonymous with developing countries, and as the Initiative continues to spread across the world, opportunities will increasingly appear in more advanced economies, such as Italy. At the same time, the opportunities in Asia and Africa will continue to deepen beyond sectors such as energy, resources and infrastructure.

China’s focus on quality projects will also lead to more transparency and a concurrent reduction in the risks involved. In this regard, consultancies are well-placed to conduct due diligence of opportunities to help their clients avoid “buying wrong” or “buying expensive” when making investments. Consultancies with a wide international presence across BRI countries are especially suited to help navigate differing tax and regulatory requirements, as well as assess political and policy risks, not to mention the potential impact of cultural differences, to safeguard and maximize their clients’ overseas investments. Indeed, Zhou Xiafei, deputy secretary general of China’s National Development and Reform Commission, has stressed that BRI projects would benefit from involvement by international professional services, and management and financing firms.46 This can help MNCs and China’s SOEs navigate the various challenges and find the most suitable BRI opportunities.

Finally, BRI opportunities will continue to emerge in new sectors and geographies, with technology an area to watch as the Digital Silk Road progresses. The official “Belt and Road” portal,47 for instance, lists a slew of recent technology-led projects, including a self-driving tractor run on Chinese technology being trialed in Tunisia,48 and foreign companies being linked with Chinese suppliers through Chinese B2B platforms such as Osell and Alibaba, dubbed “matchmakers” along the Belt and Road.49

The focus now is very much on assessing each project on its individual merits, while being mindful of the overarching goal of spreading prosperity and inclusiveness.50

To be sure, BRI is the most ambitious geo-economic vision in recent history, although it has also been described as the “best-known, least-understood” foreign policy effort underway.51 China is striving to address the need for greater understanding by devoting considerable time and effort to organizing BRI events and conducting outreach. In the process, a better understanding of BRI’s motives and potential has been spreading, and greater participation has naturally followed. This, in turn, will take the Initiative even further.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.

Explore economics in the Asia-Pacific region

-

Economics: Asia Pacific Collection

-

Voice of Asia Collection

-

China economic outlook, February 2023 Article2 years ago

-

Will political tensions derail economic gains in Asia Pacific? Article6 years ago

-

Asian consumer outlook Article6 years ago

-

Global Weekly Economic Update Article6 days ago