Widening the lens Big-picture thinking on disruptive innovation in the retail power sector

To compete with new market entrants and business models, retail power companies ought to consider broadening their innovation programs. This report shares how some companies are disrupting the retail power sector by innovating across the business.

Executive summary

Disruption in the retail power sector isn’t anything new, but its pace and consequences appear to be increasing. Nonetheless, many retail power providers are not responding to the existential threats with the urgency one might expect. While the call to innovate faster and more effectively is getting louder by the minute, Deloitte’s experience with retail power providers around the world suggests that the vast majority of innovation is still focused on core operations. In other words, it’s generally about making established products and services better, rather than expanding from existing business into “new-to-the-company” business or inventing brand-new products or services for markets that don’t exist yet. This narrow approach to innovation can cause retail power companies to overlook both risks and opportunities—essentially creating “blind spots” in terms of how they may be disrupted, or, conversely, in terms of how they may grow by disrupting traditional ways of doing business.

Learn more

Download the full report

View more content for the Power & Utilities sector

Find out more on the book: Detonate: Why—and how—corporations must blow up best practices (and bring a beginner's mind) to survive

Subscribe to receive content related to energy and resources

In order to survive amid a multitude of new market entrants and new business models from existing competitors, retail power companies should consider broadening their innovation programs. To that end, this report outlines three levels of innovation ambition and defines 10 key types of innovation. It also details common blind spots in the retail power sector as identified by our specialists. Furthermore, it explains how retail power companies can avoid these blind spots or, alternatively, seize the opportunities they present, by taking a more comprehensive approach to innovation. By highlighting inspiring examples from around the globe, this report aims to show how some companies are disrupting the retail power sector by innovating across the business. This generally implies going beyond core optimization to create transformational breakthroughs by integrating several types of innovation together.

Introduction

Some would say that working in the retail power sector today is like getting caught in a wind storm. No matter which direction you turn, something is flying at you. While regulatory constructs vary, utilities around the world are generally being disrupted by government policy, economics, changing customer habits and expectations, and of course, by technology. The latter in particular is upending business as usual by lowering competitive barriers to entry. Especially within the wider expanses of deregulated markets, many new entrants are using digitization and disruptive technologies to challenge established business models. As a result, a whole new breed of company has emerged that more closely resembles an online consumer retailer rather than a traditional retail power provider.

Though disruption seems to be widely perceived as the biggest issue of the day, innovation may carry even more weight. Innovation underpins disruption, and disruption provides opportunities for growth. Without the capabilities to re-envision every aspect of how business is done and to act upon those insights, companies can neither respond to disruption effectively nor create new opportunities by disrupting the existing state of affairs.

Innovate or die

While the imperative to innovate is as old as business itself, the term has ambiguous connotations. “Innovate” is a fuzzy word that is often long on enthusiasm but short on substance. To make innovation more meaningful for business, Doblin, a Deloitte business,1 offers the following definition: Innovation is the creation of a new, viable business offering. Simple enough, but more to the point:

Innovation (as separate from invention) is the creation of a new (to our market or the world), viable (creating value for both our customers and ourselves) business offering (ideally going beyond products to platforms, business models, and stakeholder experiences).

Granted, it’s a lot easier to say innovation than to do it, no matter how one defines it. But, in the retail power sector, where disruption is well under way, some companies may be running out of time to develop the capabilities to do innovation well. Based on interviews with several of our power and utilities specialists across five different geographies, traditional retail power companies have generally begun to innovate in select areas—such as using digital technologies to reduce administrative costs or to improve the customer experience—but they have yet to make innovation a strategic priority and to act upon it in a consistent or integrated way. While some startups and a handful of progressive incumbents are shaking up the sector with ground-breaking ideas, many traditional retail power companies generally have some way to go in embracing innovation as a means of growing revenues and transforming their businesses.

Innovation ambition

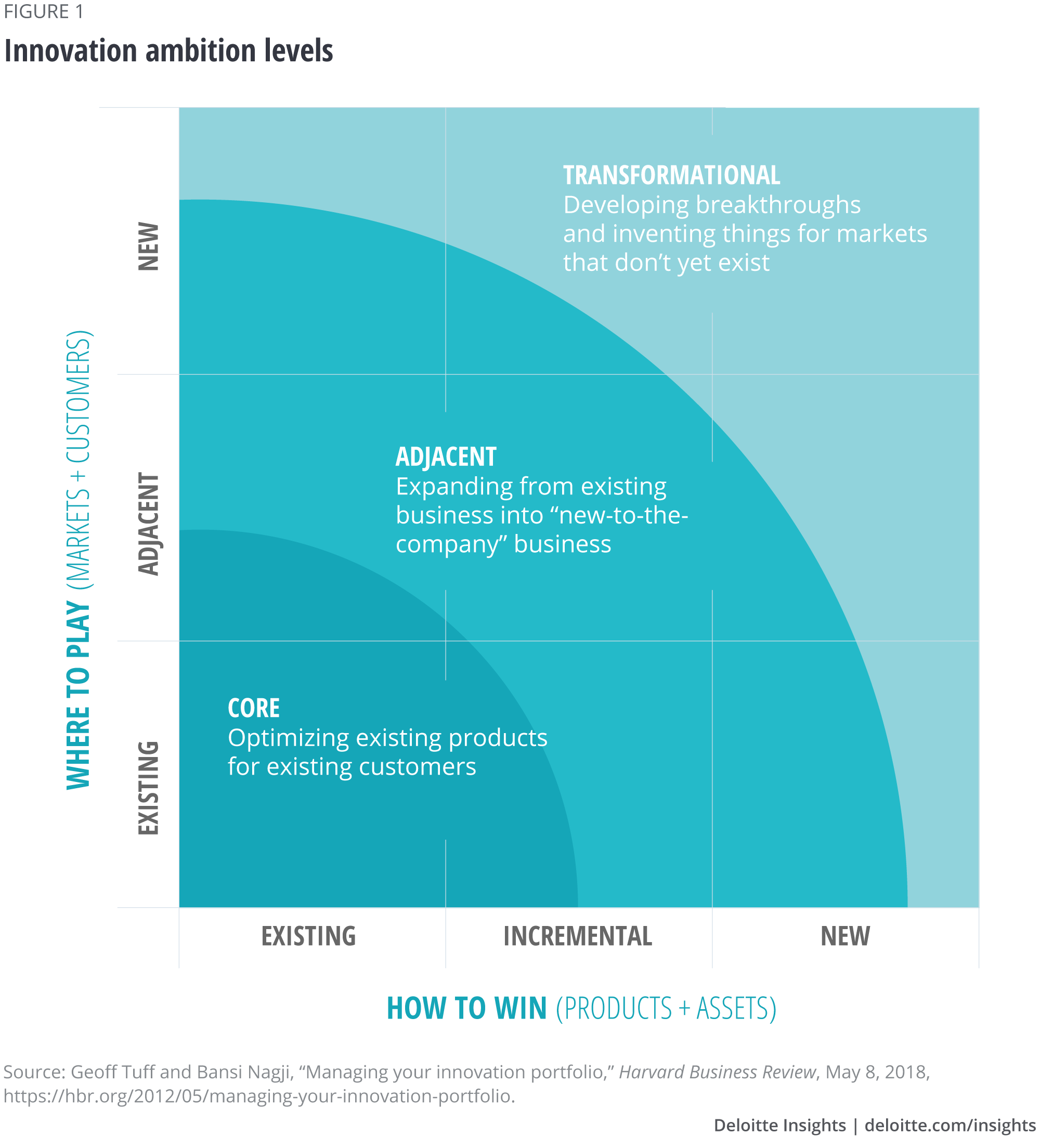

Doblin’s Innovation Ambition Matrix (figure 1) provides a framework for understanding where a company stands in terms of its commitment to innovation. Within the matrix, innovation can occupy one of three “ambition levels,” which define its purpose or result:

- Core innovations optimize existing products for existing customers

- Adjacent or incremental innovations expand existing business into new-to-the-company business

- Transformational or new innovations are breakthroughs and inventions for markets that don’t yet exist.

Doblin research suggests that the most successful innovators manage their innovation efforts and investments as a portfolio of activities that is balanced across the three ambition levels.2 Until recently, this research found that companies with well-balanced innovation portfolios spent an average of 70 percent of their investments on innovation at the Core level, 20 percent at the Adjacent level, and 10 percent at the Transformational level.3 In their 2018 book Detonate: Why and How Corporations Must Blow Up Best Practices (and bring a beginner’s mind) to Survive, authors Geoff Tuff, a senior leader in Deloitte Consulting LLP’s Innovation and Applied Design practices, and Steven Goldbach, chief strategy officer for Deloitte LLP, contend this “golden ratio” has shifted even further away from the Core level (i.e., optimizing existing products for existing customers).4 In a world where disruption can upend entire sectors, the authors maintain the ideal investment ratio has likely shifted to 50 percent Core, 30 percent Adjacent, and 20 percent Transformational.

Despite the call to think differently about innovation, companies generally are not responding in kind to the existential threats they are facing. Typically, Deloitte’s experience with retail power providers suggests that the vast majority of innovation is still focused on the Core. In other words, it’s about making existing products and services better for existing customers.

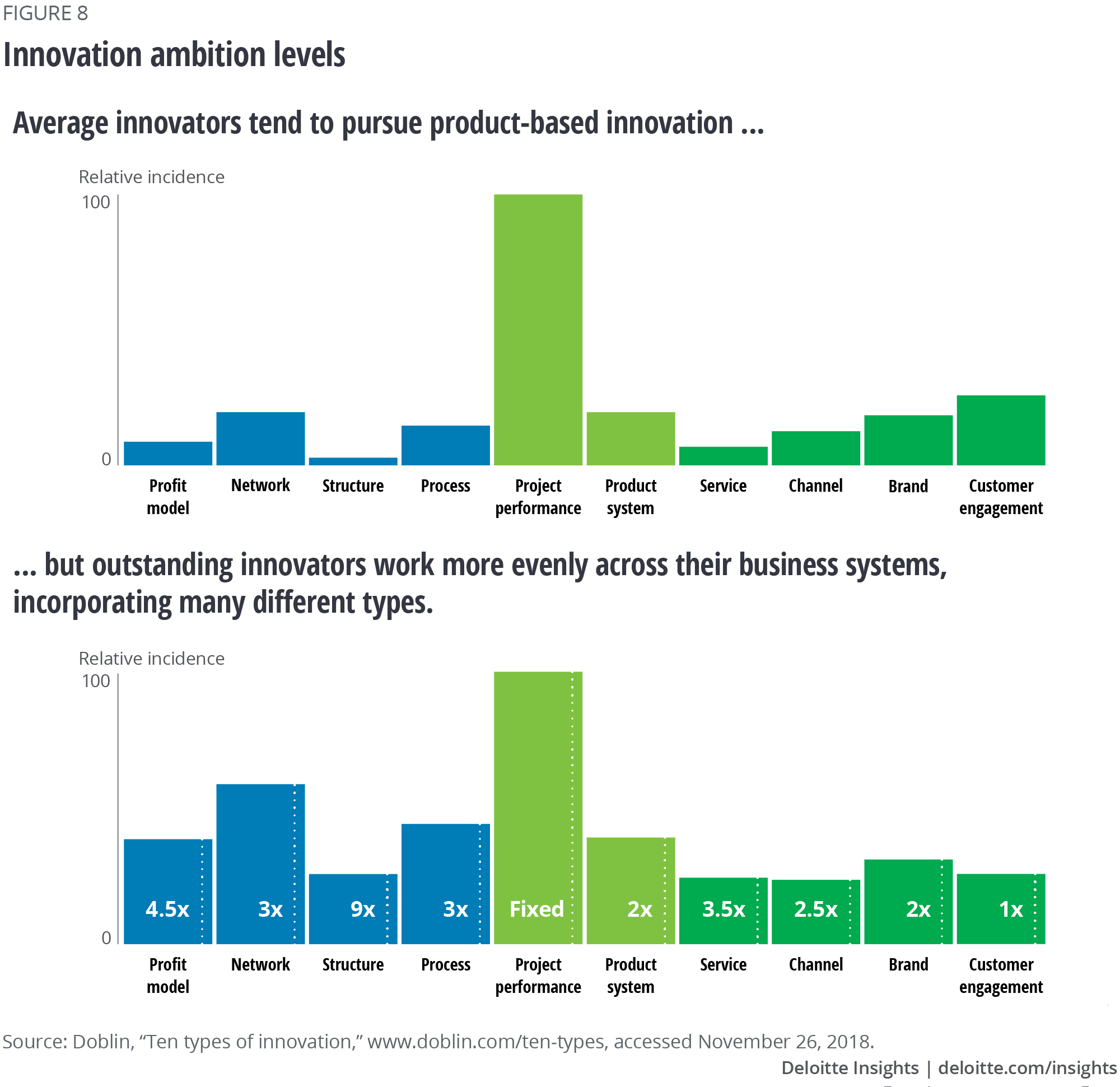

Core ambitions can generally be achieved by focusing on one or two types of innovation. In contrast, achieving Adjacent and Transformational ambitions typically requires companies to focus on several types of innovation at once. At present, most retail power companies tend to focus on Core ambitions, which means they don’t typically weave in all of the types of innovation that they should. This focused approach can cause them to overlook both risks and opportunities.

Innovation in action: Aggregation of residential distributed energy resources

New business models are emerging that aggregate customer-sited generation (i.e., rooftop solar panels) and energy storage (i.e., electric vehicle batteries or residential systems) to provide a range of services to utilities, grid operators, and electricity customers. Powered by artificial intelligence, blockchain, and predictive analytics, aggregation can offer greater flexibility for utilities and greater value for residential and business customers. OVO in the United Kingdom offers an example of business model innovation based on aggregation.

Through collaboration with Nissan, OVO is tying together its customer proposition for electric vehicles, home storage, and energy supply. At present, the company is trialing an offering for residential consumers with solar panels that combine VNet, OVO’s intelligent energy technology, with the capabilities of the innovative Nissan XStorage Home system.5 Through the technology, intelligent algorithms manage the network of batteries so that they store energy when demand on the grid is low and more likely greener, and then release it when needed to help balance the grid.

The company has also announced its intention to launch a vehicle-to-grid (V2G) offering for private customers buying the new Nissan LEAF, which could allow them to sell energy back to the grid at peak times.6 Even without the V2G component, OVO provides electric vehicle owners with an innovative home energy plan that combines fixed electricity prices for two years; the ability to charge one’s vehicle with 100 percent renewable energy; free membership in a large, public charging network; and an off-peak charging tariff that makes electric vehicle charging even more economical.7 By tapping into several trends at once, these offerings span six types of innovation. Or, put another way, they involve implementing new configuration models and enhancing the experience for stakeholders as much as they do creating new offerings.

For further explanation of the ten types of innovation, refer to figures 7 and 8.

The blind side

Based on a focus group comprising 40 Deloitte power and utilities specialists from around the world, we identified five “blind spots”: rapid development of battery storage, ecosystem convergence, new market entrants, regulatory environment, and cyberthreats. These blind spots are commonly found among retail power companies, which can be traced back to a narrow approach to innovation:

- Rapid development of battery storage technology. By the time you finish reading this sentence, battery technology has probably advanced in some way. Continuous innovation in this space has been generating cost reductions, performance improvements and/or new applications for battery storage at a pace that has been surprising to some. As of mid-2017, the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) had identified more than 18 use cases for battery storage.8 One of the most compelling developments in this arena is the emergence of new business models that aggregate customer-sited storage to provide a range of services to utilities, grid operators, and electricity customers. As noted in the recent Deloitte report, Supercharged: Challenges and opportunities in global storage markets, aggregation—powered by artificial intelligence (AI), blockchain, and predictive analytics—could provide greater flexibility for utilities and developers and greater choice for residential, commercial, and industrial customers.9 It could also demand more effort and investment from retail power providers, who should stay abreast of developments and identify where to play in this space.

- Ecosystem convergence. Electric vehicles straddle the automotive and the retail power sectors. Smart cities blend Internet of Things (IoT), microgrids, renewable power, self-driving vehicles, energy management, and battery storage, among other technologies. Wherever you look, ecosystems are converging, if not colliding. What is the role of the power provider amid this fusion? A leader, integrator, and innovator—or a pipes and wires provider? Some retail power companies are testing the extent of ecosystem convergence through pilot projects. However, because there is no single ecosystem right now, platforms and configurations have yet to be standardized. Thus, offering integrated solutions to customers generally comes at a high cost. While some have pressed onward despite this challenge, others have yet to enter this space even on a trial basis. With their “heads down” on their core businesses, these retail power companies may be misjudging the velocity of convergence and the need to adjust their business strategies in order to compete on what is effectively becoming a whole new playing field.

New market entrants. As illustrated by the aforementioned aggregation example, technology is bringing new players and more competition into the value chain. For instance, Flux, based in New Zealand, offers an all-in-one platform that enables virtually anyone to launch a retail energy business and run it from end to end.14 It was originally created as the engine behind Powershop, a power company operating with a similar model in New Zealand, Australia, and the United Kingdom. Recognized for its innovative shopping approach to energy, the Flux platform is now available as an out-of-the-box offering to aspiring power retailers around the world.15

By making it easier for companies to implement new business models, technology is inviting not only startups but also established players from adjacent industries to enter the retail power sector. For example, consider Royal Dutch Shell’s move into the retail power and solar business. The oil and gas organization recently purchased First Utility, an independent UK power provider, as well as MP2 Power, a commercial and industrial retail power provider with a significant existing book of business in the North American market.16 These moves are part of a strategy to make electricity the fourth pillar of its business, alongside oil, gas, and chemicals.17

- Regulatory environment. In many parts of the world, the utility regulatory structure has yet to catch up with disruption in the sector. With policy constraints to contend with, retail power providers in some regions may feel hamstrung in how effectively they can adapt to disruption, since incentives may not be aligned with the new widely recognized priorities of de-carbonization, decentralization, and digitization. How can retail providers codevelop an updated regulatory model that allows enhanced services through technology but doesn’t undermine the whole basis for the retail power business? The challenge of answering this question may be a blind spot, since utilities and regulators alike would need to move away from the traditional model of cost recovery and allowed rate of return on investments, which has typically provided stability to investors and other stakeholders. However, utilities may also be underrating the upside potential of innovation within the regulatory construct. New policies and regulations could help retail power providers to achieve Adjacent and Transformational breakthroughs by incentivizing new technology-enabled business models such as management of energy storage and delivery of predictive analytics, forecasting, and other business services. Either way, retail power providers increasingly see the regulatory environment as an opportunity for collaborative innovation.

Cyberthreats. With cyberattacks making headlines around the world, one might question how cybersecurity could be a “blind spot” for retail power providers. The issue is not lack of awareness; however, it seems to be an inadequate realization of what it might take to stay ahead of the rapidly evolving threat landscape. Some cybercriminals are highly skilled, well-organized, and well-funded; others are small groups or individuals who can do considerable damage with relatively little knowledge, simply by using prebuilt tools and infrastructure available through the cyber underground. Whether they’re acting alone or as part of a sophisticated operation, malicious actors are becoming more proficient at evading detection, while their motives are becoming more diverse.

The threat landscape is expected to become even more complicated as the retail power sector increasingly adopts smart technologies, leverages IoT, and digitizes its back-office systems. As a byproduct of these efforts, corporate office systems and operational technologies are becoming more tightly mingled and interdependent than ever before, opening new avenues for accidental or targeted disruption. Consequently, some retail power companies may be underestimating the multiplicity of the attack vectors as well as the pace of innovation required to keep up with, across people and processes as well as technology.

Innovation in action: Green power and local sustainability

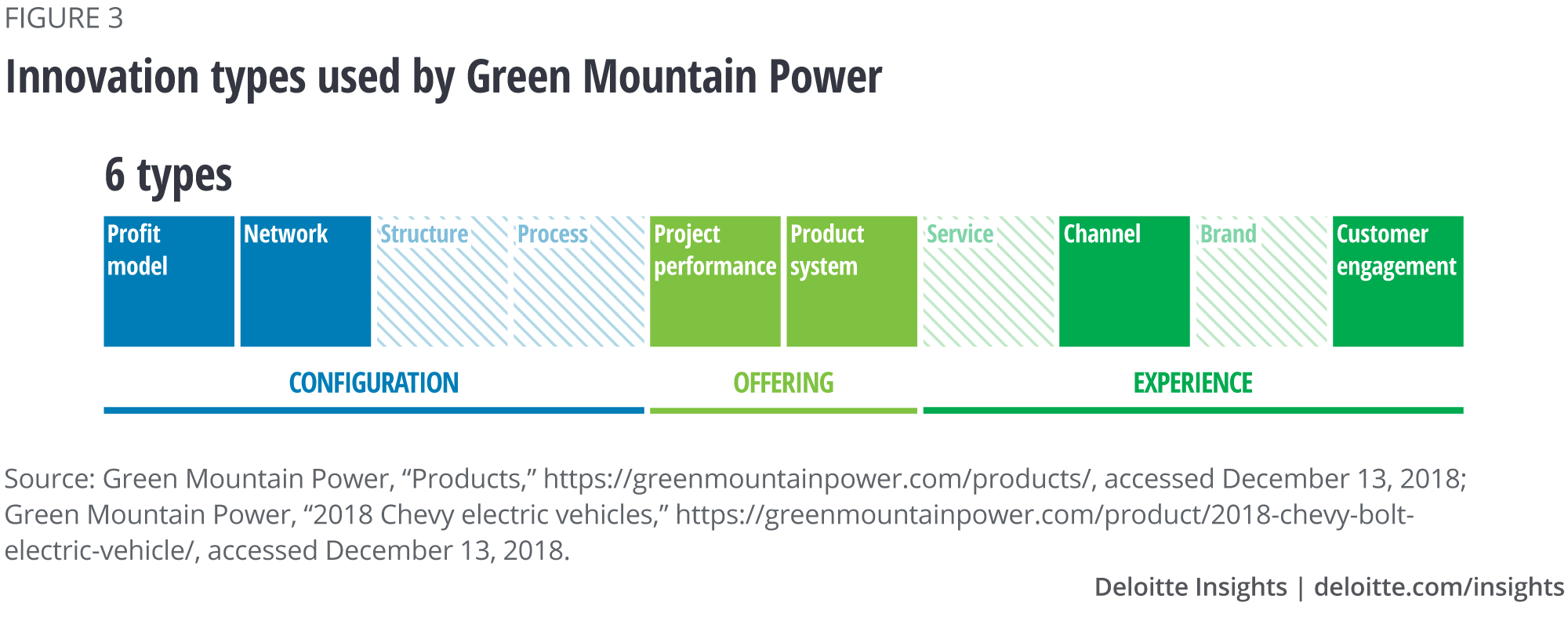

The local utility in the US state of Vermont, Green Mountain Power, struck a deal with Tesla in 2015 when the first generation of the Powerwall, a home energy storage system, came on the market. Through the deal, Green Mountain Power is now working to install Powerwalls in up to 2,000 homes.10 Customers can lease the system or buy it outright from the utility at a significant discount. In exchange, customers agree to allow their units to be used by the utility as a “virtual power plant” to support its grid. According to Green Mountain Power, not only can the Powerwall improve reliability for those participating in the program, but it can also lower costs for everyone on the grid by reducing transmission and capacity expenses during peak energy times.11

The program provides an example of offering innovation in the form of enhanced product performance and product systems, but, less noticeably, it also incorporates Configuration and Experience innovations of the following types: profit model (i.e., a leasing arrangement and ability to earn bill credits), network (i.e., partnering with Tesla), channel (i.e., Tesla installs the battery storage unit), and customer engagement (i.e., a simplified purchasing/leasing experience and making people feel they are part of the “green” movement).

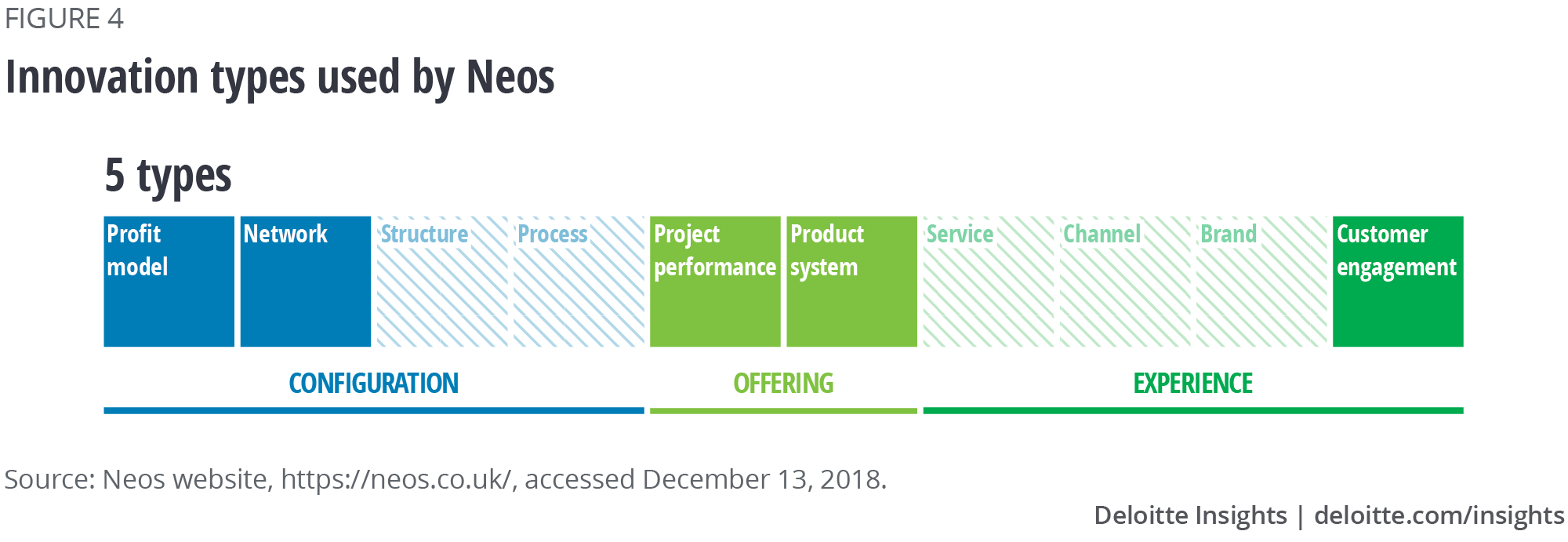

Innovation in action: IoT-enabled home solutions

Home insurance may seem distant from a traditional retail electricity business but, upon closer inspection, may be more closely related than one might think. Enabled by sensor technology and wireless connectivity, Neos in the United Kingdom is trying to rewrite the rules of the insurance industry and illustrating the potential for IoT to connect seemingly unrelated sectors in the process.12 Neos sells insurance products with a twist: They come with several mainly third-party, internet-connected sensors that customers can install and subsequently monitor with the Neos app.13 The app is designed to alert users to potentially problematic events, such as the air temperature dropping below freezing or water starting to leak under a sink. And, if necessary, it can connect customers to repair services for rapid remediation. By focusing on proactively mitigating some of the most common home-related risks, Neos can offer highly competitive rates. While Neos is an insurance industry startup, and not a retail power provider, it appears to demonstrate how IoT can be used to drive transformative innovation. It also points to the potential for network and product innovations within the retail power sector. Could utilities install sensors on power lines, heating units, air conditioners, etc. to stem the risk of fire or water damage from a malfunction? Could smart meter data be used to provide insight into a customer’s insurance risk profile (i.e., is the customer home during the day and thus at less risk for burglary)? These and similar questions offer compelling food for thought as ecosystems converge.

The company has also invested in projects to develop charging stations for electric vehicles across Europe, and it has signed agreements to buy solar power in Britain and develop renewable power grids in Asia and Africa.18

With the door to the sector being flung wide open, some retail power providers may be underestimating the influx of new competitors and the downward margin pressures that commoditization often brings. Even if their competitive calculus is correct, they will still need to find new ways of creating value if they are to stand out from the crowd.

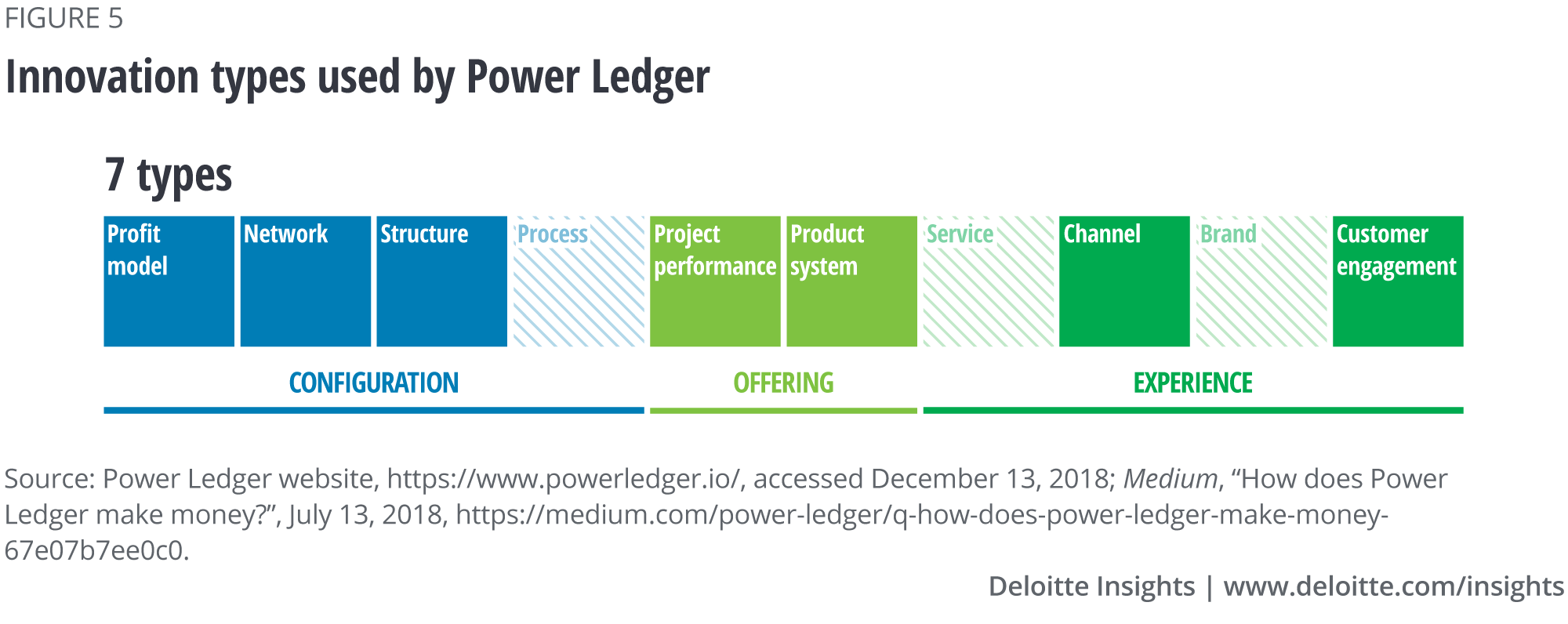

Innovation in action: Peer-to-peer trading platforms

Australia-based Power Ledger provides a peer-to-peer (P2P) marketplace for renewable energy and seeks to “democratize power” using blockchain technology.19 As explained in the company’s promotional video, “the energy market isn’t geared up to buy home-grown electricity any more than the supermarket is geared up to buy home-grown tomatoes.”20 The Power Ledger platform strives to solve that problem by using blockchain technology and a token system to allow “prosumers,” or those who own rooftop solar panels, to sell electricity directly to their neighbors. Through Power Ledger hardware and an app, participants can decide who to sell their electricity to and at what price by trading units called Sparkz.21 These units are backed up by a blockchain bond called POWR Tokens, which are designed to make trades easy, trustworthy, and immediate. Blockchain-enabled P2P trading platforms such as Power Ledger provide an example of truly transformational innovation. To get there, the company, which was founded by experienced executives from the traditional retail power sector, combined several types of innovation, including profit model, network, structure, product performance, product system, channel, and customer engagement. By leveraging advanced technology, the founders not only invented an entirely new-to-the-market offering, but they also avoided the blind spot of “new market entrants” by differentiating their value proposition. Power Ledger’s customers aren’t just trading electrons and getting a better deal on either side of the transaction; they’re empowering each other to participate in the transition to a “cleaner, greener, and more locally generated energy future.”22

Innovation in action: Storage as a service

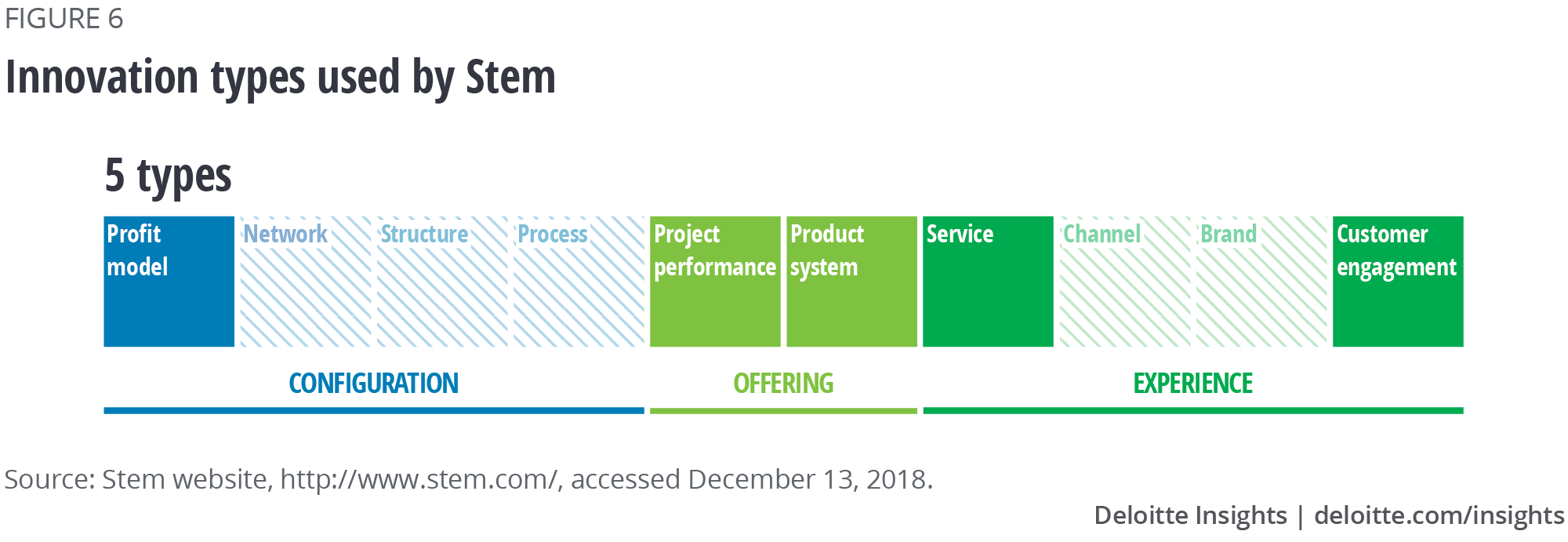

Via a platform that uses artificial intelligence to dispatch and reconfigure a network of customer-sited batteries at a moment’s notice, US-based Stem offers storage as a service to commercial and industrial customers.23 The offering is designed to help organizations automate cost savings by shifting their energy use away from the most expensive times—all without manual intervention such as turning off heating, ventilation, and air conditioning systems and lights. Together, Stem’s customers form one of the world’s largest energy-storage network, which can provide fast-acting, dispatchable capacity, ramping support, and ancillary services to utilities and grid operators.24 Beyond pioneering a new product for two complementary customer segments (i.e., businesses as well as utilities and grid operators), the company has employed other types of innovation in its efforts to win customers and fuel its growth. These include a focus on turnkey installation, operation, remote monitoring, and maintenance of the battery systems; a more customer-friendly subscription model that requires no upfront payments; automated and verifiable savings; customer support; and the ability to earn revenue through Stem’s Grid Rewards programs.25

As we will explore, retail power companies can lessen their chances of being blindsided by these vulnerabilities by adjusting their approach to innovation. The challenge for most organizations is to think about innovation more broadly.

Integrate to outperform

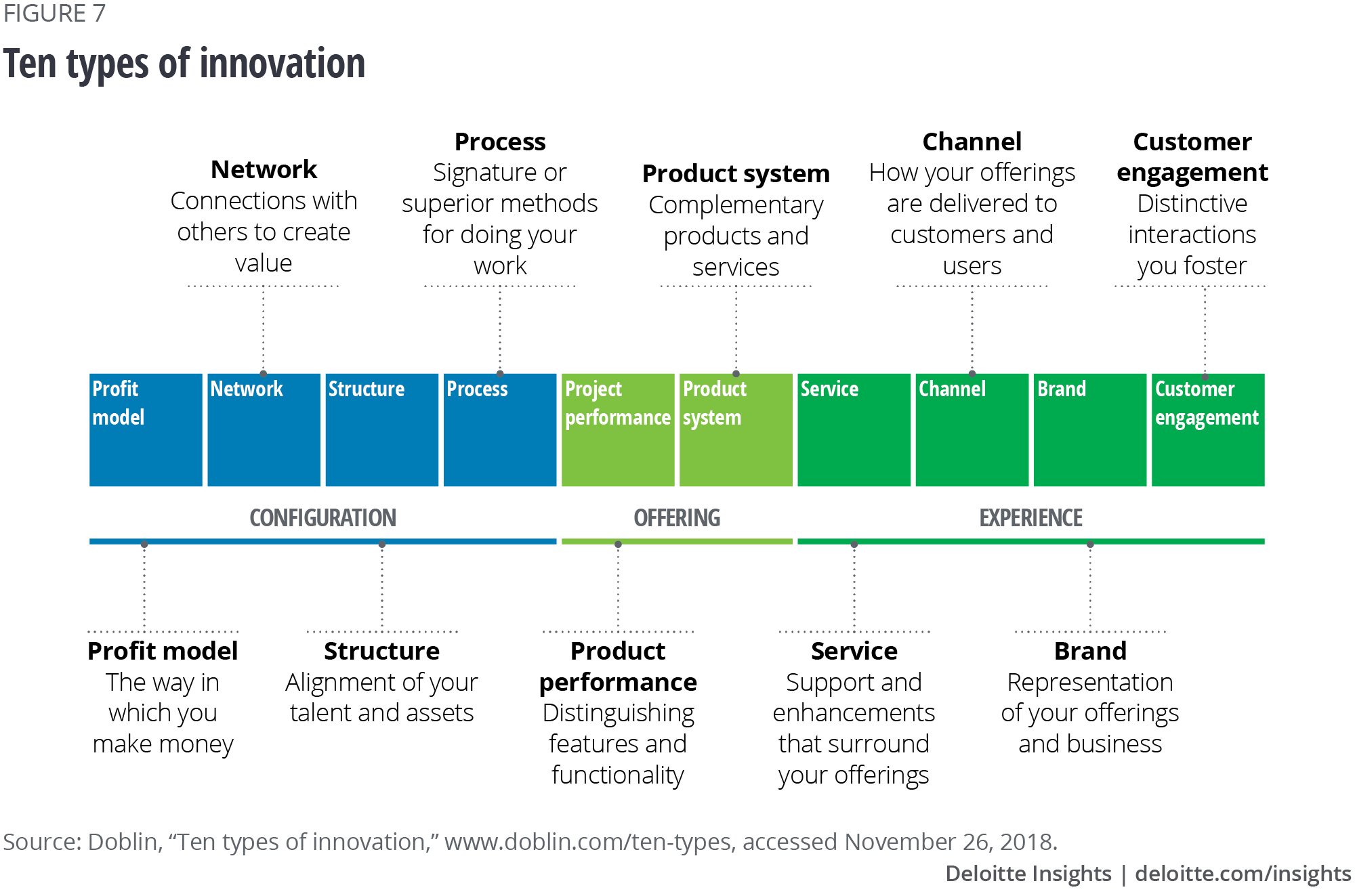

Until recently, the retail power sector had been relatively insulated from consumer pressure to innovate faster and had not been directly affected by exponential technology shifts. Thus, it is generally less mature in its innovation capabilities than industries that felt the brunt of these forces earlier, such as automotive, retail, financial services, and technology, media, and telecommunications. Though every organization is different, many retail power companies still think of innovation in terms of updated software and systems, meaning many are focused on improving administrative efficiency and enhancing the customer experience, often by adding mobility and other digital capabilities. However, these incremental improvements represent a small part of the innovation compendium. Indeed, Doblin identifies ten distinct types of innovation across three categories (figure 7):

- Configuration innovations apply to profit models, networks, structures, and processes. This comprises the back-of-the-house activities needed to develop the offering.

- Offering innovations apply to product performance and product systems. This is what companies produce.

- Experience innovations apply to services, channels, brands, and stakeholders. This is how an offering is delivered to customers and how stakeholders are engaged as a company performs its business activities (e.g., through regulatory affairs and community relations programs).26

A comprehensive approach to innovation matters because it directly correlates to performance. Doblin research shows that top innovators across all industries outperform the S&P 500 in relation to how many different types of innovation they pursue. It also finds that the most shareholder value accrues not from Offering innovations (i.e., product performance or product system), but rather from Configuration innovations or Experience innovations.

Based on these findings, in order to be truly disruptive, or to create transformational breakthroughs, companies should weave in multiple types of innovation—usually five to six types or more (figure 8). Retail power companies generally have a high degree of awareness that they need to innovate faster and more effectively. However, they are not necessarily thinking about comprehensive or holistic disruption. More likely, they are intending “to do something” with blockchain or another emerging technology. However, the technology itself isn’t transformative; it has to be integrated with several other types of innovation if it is going to disrupt the status quo and produce the desired business outcomes.

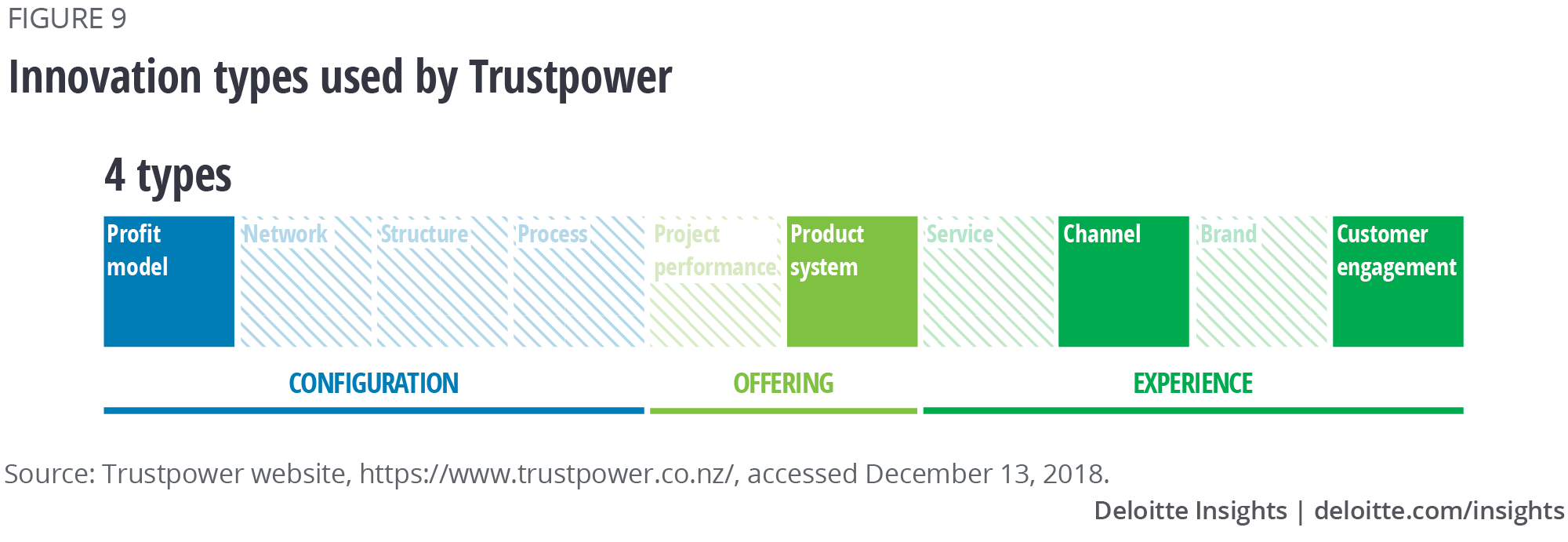

Innovation in action: Bundled home services

There has been much speculation about the potential for utilities to leverage their status as a trusted provider to offer adjacent home services. Trustpower in New Zealand was a first-mover in pursuing this strategy.27 Today, the company bundles power, natural gas, phone, and internet plans, offering its customers competitive rates and the convenience of a single bill.28 Rather than just providing a list of fixed services, the company tried to bring them together in ways that optimize value for the customer, thus weaving channel and customer engagement innovation into its offerings.29 As with a number of the innovation in action examples, the competition moves fast to follow successful innovation. In New Zealand, bundling is now becoming a mainstream offering with competition coming from both energy and telecommunications companies.

Indeed, integrating multiple types of innovation is exactly what disruptors in the retail power sector are doing. The “Innovation in action” sidebars (found throughout this report) feature some of the most innovative developments in the retail power sector as identified by our specialists. More specifically, these snapshots illustrate how some companies are disrupting the sector and transforming their businesses by weaving several types of innovation together.

Digital’s role

As demonstrated in the “Innovation in action” examples, digital transformation provides the foundation for disruptive innovation by enabling a multipronged approach. It allows companies to focus on multiple types of innovation at the same time by breaking down functional silos and improving collaboration across the business.

Innovation in action: Open data

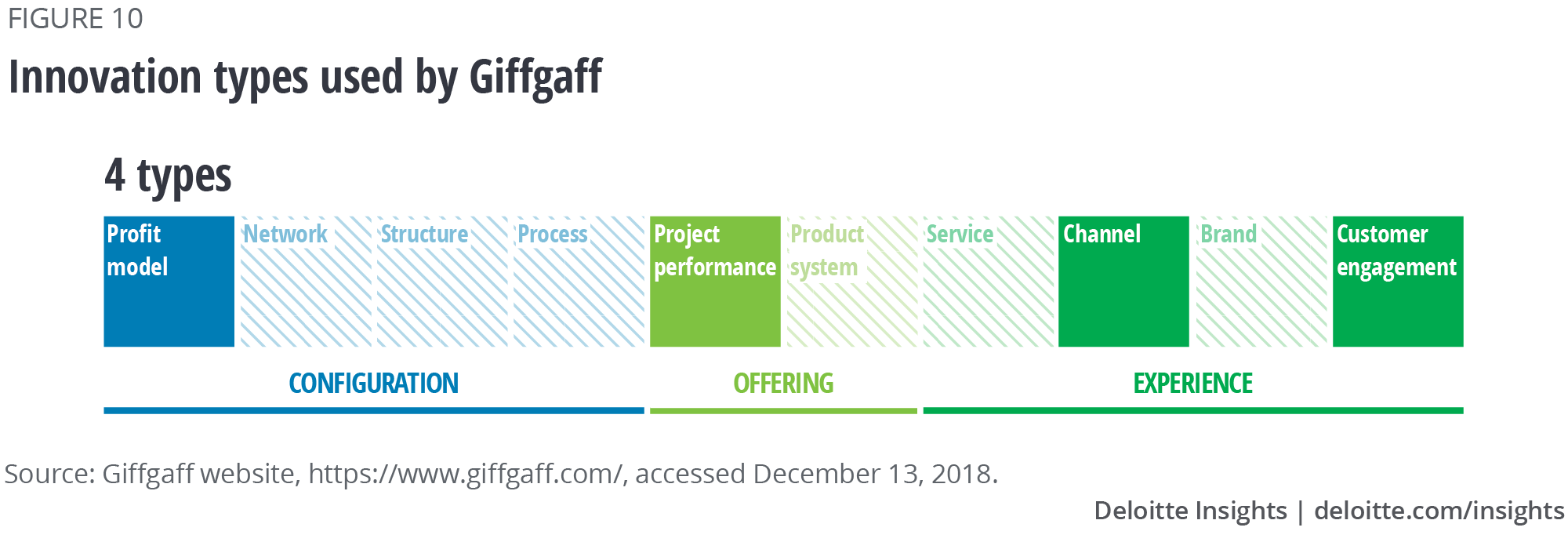

New business models and pricing programs that leverage the data collected by smart meters have begun to emerge. Some examples of this “open data” include comparison sites that help consumers search for better price; startups that mine customer data to gain insight in order to tailor offerings to niche markets; and new brokerage models where companies compare customers’ current tariffs and/or bundle energy data with other data from the home, making it easier for them to identify the best deals and switch providers. Giffgaff in the United Kingdom provides an example of the latter.30 This telecom company offers its customers a way of aggregating their data and switching various services. In addition to assessing mobile-phone offerings, customers can also compare loans, credit cards, car insurance, and energy prices on the Giffgaff site.31 This “open-data” model is starting to be replicated across the globe, particularly as smart meters become more prevalent and markets deregulate. The speed of change within the sector is likely to accelerate as electricity usage data becomes more widely available and government-led initiatives support greater transparency into tariffs and billing. Power of Choice in Australia offers an example of this trend. Through detailed smart-meter data, this government-led, industrywide program gives consumers more opportunities to make informed choices about how they use electricity products and services.32

Innovation in action: Digital attackers

Some established utilities are employing an innovative tactic to accelerate digitization of their retail businesses.33 Similar to what has been done in other sectors, they are setting up new “challenger brand” subsidiaries.34 These new companies are wholly based on digital processes and operate independently from the utilities’ core units.35 Since traditional utilities often have complex structures, this streamlined approach allows them to develop, test, and optimize digital processes and services much faster than otherwise possible. In many instances, utilities can develop and launch a challenger brand for the retail business in less than a year, giving them a chance to jump over several intermediate stages and innovate at a pace that is typically only found within startups.36

Conclusion

A rapidly evolving retail power market is forcing companies to either disrupt or be disrupted. However, today many organizations are still tinkering in the Core, perhaps because they see disruption on the horizon, but the answers are not clear. This narrow approach to innovation can leave them exposed to blind spots, which are generally not being addressed as the existential threats that they are. As we have observed in other industries facing similar conditions, the remedy often involves taking a portfolio approach to innovation as illustrated in the Innovation in Action case studies featured in this report.

For many retail power companies, this could involve investing more in Adjacent and Transformational innovations. It could also entail focusing on multiple types of innovation at once, including leveraging new platforms such as renewables and battery storage, as well as digital enablers such as smart meters, blockchain, and AI. By innovating across the enterprise with the help of new technologies, our experience suggests companies can lessen the probabilities of being blindsided while improving the odds of finding new ways to grow.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.

Explore more on Innovation

-

The innovation paradox Article6 years ago

-

Forget fail fast Article6 years ago