A new mindset for public sector leadership Take the #TenYearChallenge

10 minute read

28 June 2019

- Rebecca George United Kingdom

- Alexander Massey United Kingdom

- Adam King United Kingdom

- Ed Roddis United Kingdom

Government and public services have changed substantially in the past decade and so have the demands on public sector leaders. This article sets out the new capabilities that the sector’s leaders need today – and the new mindset they will need to thrive in the future.

Introduction

Have you taken the #TenYearChallenge? For the uninitiated, it is a social media dare in which people share a photo of themselves from 2009 alongside a current snap. Whether you join in or not, it is a reminder of how much we – and the world around us – change over a decade. For leaders in government and public services, it raises three questions. How has the public sector environment changed in the past ten years? What has this meant for the capabilities its leaders now need? And, crucially, what can leaders do now to prepare themselves for the ten years ahead?

The public sector in 2009

Learn more

Explore the government and public services collection

This article is featured in Deloitte Review, issue 26

Download the issue

Learn about Deloitte’s services

Go straight to smart. Get the Deloitte Insights app

The public sector was in a very different place in 2009. In the UK, for example, the size of the government workforce was at its highest level since records began and health spending was at a historic high.1 But as Prime Minister, Gordon Brown, dealt with the fallout from the global financial crisis, the opposition leader, David Cameron, warned of a coming ‘age of austerity’. In the years that followed, austerity under Cameron’s government drove down budgets and headcounts across public services, while at the same time stimulating new business models, a shift to shared services and an emphasis on digital transformation. And now, in 2019, leaders across the UK public sector are grappling with various challenges, such as alleviating citizens’ demand for their services, driving inclusive economic growth and managing the implications of the UK’s exit from the EU.

Brexit aside, most of these trends are equally evident in governments and public sectors around the world. Spending power has fallen, public sector workforces have shrunk, organisational models have diversified and technology is central to change, while citizens’ expectations have continued to soar.2

The breadth of public sector leadership

Leadership in the public sector is a broader concept than many commentators acknowledge. Think of all the leadership positions across government and the public services: school principals, medical directors, military officers, police chiefs, government officials, heads of service and research scientists, to name but a few. Then there are directors and chief executives of local government, healthcare providers, educational institutions and more. And there are non-executive and elected representatives at multiple levels. Some of these jobs require deep technical knowledge, some daily interaction with citizens, and others an ability to manage spending negotiations with finance ministries and departments. Leadership also takes place at all levels in an organisation – not just in the C-suite. In other words, public sector leadership is diverse across multiple dimensions.

The public sector mission however, in many cases, is timeless. In local government, officials and elected representatives will always want to make their area a great place in which to live, work and invest. In healthcare, clinical and non-clinical staff will always want the best outcomes for patients. And in government, departmental officials will always want to develop workable policies and deliver programmes that bring political commitments into being. What has changed across the entire public sector is the environment in which these missions are pursued – and this has provoked at least five fundamental shifts in what is expected of public sector leaders.

Five shifts in what is expected of leaders

The first shift is that more than ever, creativity is needed to get results. In this age of budget restraint, public sector bodies often need to ‘make do and mend’, finding new and creative ways to deliver results. This often involves working with the private and voluntary sectors, which means that relationships need to be built with stakeholders in very different organisations with very different cultures. It can also mean that leaders need to embrace new technologies and iterative, agile approaches to change, not least in digital transformation where success can depend on the courage to experiment, fail fast, and adjust in order to keep a project moving forward.

Second, leading in the public sector has become more challenging and relentless than ever, and as a result, personal resilience has become a ‘must have’. Leaders tend to be talented people who are excellent at what they do, but in today’s public sector they are more stretched than ever. Many are asked to deliver more and more with less and less, often in uncertain policy environments. But they are all committed to doing their utmost because they have a strong sense of integrity and public service.

Resilience is a hugely positive characteristic, but it should not be mistaken for invincibility. Leaders are not impervious to stress, burn-out or other factors that can affect their wellbeing. All leaders need to understand their own limits and know when to take time out to re-energise. One of the most encouraging workplace trends in recent years is that taboos about mental health in the workplace are increasingly breaking down. The best and boldest leaders have become champions for the wellbeing of others, as well as guardians of their own.

The third shift in the past ten years is a blurring of the limits and boundaries of leadership. Fewer public sector leaders operate solely within their own organisation. At a local level, services increasingly converge around the citizen as the most effective way to improve outcomes, and nationally it’s hard to separate public health from education, national security from transport and border security, housebuilding from homelessness, and infrastructure projects from industrial strategies.

As a result, in order to make progress the best public sector leaders are working together and ignoring traditional boundaries. This has changed their approach from ‘direct’ organisational leadership to ‘networked’ leadership. Leaders now need to connect effectively with peers and exert influence over people who are outside their hierarchy – and this requires different skills and behaviours from the old command-and-control approach. This shifting boundary between the public, private and third sectors means that collaborative system leadership is more important than ever.

The fourth shift is that the public sector has become more complex. Increased complexity requires leadership styles that embrace ambiguity, ask the challenging questions, and don’t look for easy answers. Where leaders have risen through a technical or specialist route, they are now likely to need a far broader set of skills and mindsets. One area where different skills are needed is in driving organisational effectiveness and efficiency, where capabilities often associated with business, such as commercial acumen, project management and innovation, have become more necessary than ever.3

The fifth shift is a result of this increased complexity: effective leaders cannot be all things to all people. We often expect public sector leaders to be experts in leading their organisation or service, with an intimate knowledge of how legislation is passed, translated into policy and delivered to time and budget. We expect them to maintain their excellent specialist knowledge, and tackle anything else that comes along – whether it be technology, new methods of contracting or new financial regulations. But in reality, they cannot do it all. That’s why public sector leaders need to be masters of prioritisation and building the right teams around them. They need to identify what matters most and focus on it, revisiting that choice continually. And they need to identify the right blend of skills they need in their teams, and how to shape it accordingly.

Looking forward: the new public sector leadership mindset

The demands on public sector leaders have changed substantially over the past ten years, but what about the next ten? What capabilities should today’s leaders and future leaders be developing? Looking ahead to 2029, our analysis suggests the public sector will change more in the next decade than it did in the last – so much so, that new capabilities will not be enough. Next generation leaders around the world will need an entirely new mindset to thrive in the future of government and public services. Let us explore the public sector’s direction of travel and what it means for leaders.

The public sector in 2029

While governments affected by the global financial crisis have stabilised their day-to-day finances over the past decade, the dominant trend for public spending in the next ten years remains downward.4 Of course, changes in political direction can affect levels of tax and spending, but demand pressures in most advanced economies and government debt levels in many are still likely to constrain public spending power in the medium term. As a result, public sectors around the world will continue to focus on cost control, managing down citizen expectations and managing up productivity.

This means that the environment for leaders will remain challenging, and support will be more important than ever. A taskforce backed by the UK government recently concluded that personal networks for leaders are at present under-developed.5 Many could benefit from peer-to-peer experience as well as the kinds of coaching and mentoring that such networks would create for support and reflection. It’s a model that, if successful, could be replicated at national level by governments around the world.

The difficult fiscal environment also means that the creativity leaders have developed in the past decade will be needed even more in the next – not least in their application of technology.

Many commentators have recognised that the world is entering a fourth industrial revolution, characterised by technologies that are bringing together the physical, the human and the digital in an entirely unprecedented way.6 While some larger public sector bodies around the world have begun realising the benefits of such technologies, Deloitte research suggests that most public sector organisations are yet to invest at scale, prioritising instead fundamentals such as cybersecurity.7 Looking ahead, public sector bodies that manage high volumes of rules-based transactions could have much to gain from robotics, and the time saved in healthcare by using technologies like artificial intelligence could be reinvested so that clinicians can spend more time with patients. A recent study into preparing the healthcare workforce for future technologies called this the ‘gift of time’.8 The potential for fourth industrial revolution technologies in government is huge. Our own analysis suggests that automating tasks using artificial intelligence could free up 96.7 million working hours annually in the US Federal government, saving some $3.3 billion – and that is a conservative estimate.9

While the public sector may be in the early days of the fourth industrial revolution, there is little doubt it will seize its opportunities in the decade ahead. Doing so means that public sector leaders have to be clear about what technology can do for their organisation. The days when those at the top could cheerfully admit to being a Luddite are coming to an end.

They will also need to understand technology’s wider impacts. By 2029, artificial intelligence (AI) will routinely be making decisions that affect people’s lives. AI-driven systems could determine the urgency of a medical appointment or the allocation of a school place, and when that happens public sector leaders will should be clear on accountability, citizens’ rights and the legal provisions about data use.

Technology will also change the size, shape and employment mix of public sector bodies. As digital and fourth industrial revolution technologies become more widespread, the number of people engaged in administrative tasks such as data entry will drop substantially while the number of skilled digital and artificial intelligence experts will rise, albeit in smaller numbers.

The loss of administrative jobs to automation should not be as brutal as many headlines suggest, but a rather more gradual process in which clerical staff are able to develop their roles as their administrative burdens are eased. That said, managing the roll-out of artificial intelligence will oblige many public sector leaders to undertake significant levels of restructuring, with all the difficulties and hard choices that entails.

Beyond restructuring, other workforce concerns are likely to preoccupy public sector leaders in the decade to come – not least, attracting the right talent. The global supply of health and care professionals is increasingly stretched, driven in part by the demands of an ageing population.10 Our research suggests that at the most senior levels, many roles are difficult to fill because they are seen as relentless and over-exposed to risk. 11

As a result, making organisations appealing as employers, able to attract, recruit and retain the best people, will be a priority for public sector leaders. Public sector bodies, like those in the private sector, will have to wage war for talent.

Approaches to staff engagement will also need to evolve. Traditional engagement channels will not be effective as the workforce diversifies, with contractors, associates and people with a portfolio career complementing the part-time and full-time employee base, all of which will work with increasing flexibility in terms of hours and location. As the workforce becomes more diffuse, leaders will have to rethink how they motivate and communicate with their staff and remain visible.

Leaders also need to keep up with the pace of social change, in order to create an organisational culture in which staff can perform at their best. Recent years have seen some welcome developments in the workplace, with corporations reporting on gender pay gaps and the best employers investing in inclusive treatment of staff. The public sector leaders of 2029 will have to be champions for all their employees, celebrating diversity and attracting talent by empowering people to be themselves at work.

Research into millennial preferences shows that many young professionals want to work for organisations that make a positive impact.12 That should work in the public sector’s favour in the battle for talent, but many public bodies are yet to make the most of this advantage in their recruitment efforts.

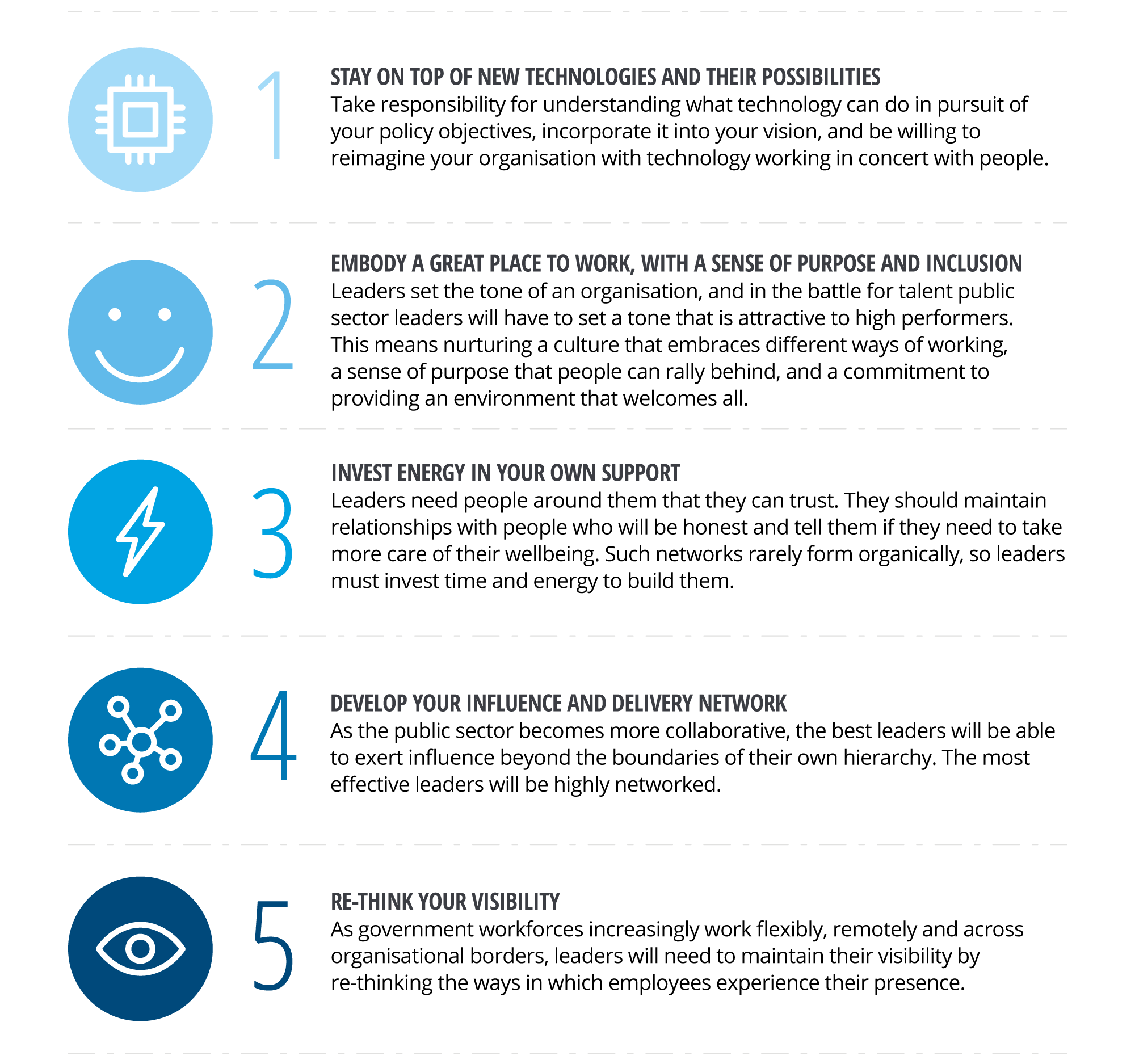

This assessment of the next decade suggests that public sector leaders will need to adapt their mindset to meet the challenges ahead. We conclude that leaders at all levels in the public sector can take five actions now to tilt their thinking towards the future.

Public sector leadership is not easy, and never has been. But recognising how the world is changing and getting on the front foot with the right leadership development can go a long way to help leaders make the most of their abilities and get ready for the future. So, take the #TenYearChallenge by setting aside some time to reflect on how your leadership demands have changed over time, and how they could change in the years to come.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.

Explore the Government Trends Collection

-

Introduction Article5 years ago

-

Innovation accelerators Article5 years ago

-

Nudging for good Article5 years ago

-

Citizen experience in government takes center stage Article5 years ago

-

Anticipatory government Article5 years ago

-

Smart government Article5 years ago