5G: The new network arrives TMT Predictions 2019

15 minute read

12 December 2018

Although it will take years for 5G to replicate 4G’s marketplace dominance, its speed, capacity, latency, and penetration make 5G an opportunity many telecommunications operators can’t—and won’t—refuse.

Deloitte Global predicts that 2019 will be the year in which fifth-generation (5G) wide-area wireless networks arrive in scale. There were 72 operators testing 5G in 2018,1 and by the end of 2019, we expect 25 operators to have launched 5G service in at least part of their territory (usually cities) with another 26 operators to launch in 2020, more than doubling the total. Further, we expect about 20 handset vendors to launch 5G-ready handsets in 2019 (with the first available in Q2), and about 1 million 5G handsets (out of a projected 1.5 billion smartphone handsets sold in 2019) to be shipped by year’s end. One million 5G modems (also known as pucks or hotspots) will be sold, and around a million 5G fixed wireless access devices will be installed.

At the end of 2020, we expect 5G handset sales (15–20 million units) to represent approximately 1 percent of all smartphone sales, with sales taking off in 2021, the first year in which retailers will sell more than 100 million 5G handsets. The most noticeable benefits of these first 5G networks for users will be faster speeds than today’s 4G technology: peak speeds of gigabits per second (Gbps), and sustainable speeds estimated to be in the hundreds of megabits per second (Mbps).

The three main uses of 5G—in the short term

Learn more

Listen to the related podcast

Watch the video or view the infographic for this prediction

View TMT Predictions 2019, download the full report, or create a custom PDF

In 2019 and 2020, 5G wireless technology will have three major applications. First, 5G will be used for truly mobile connectivity, mainly by devices such as smartphones. Second, 5G will be used to connect “less mobile” devices, mainly 5G modems or hotspots: dedicated wireless access devices, small enough to be mobile, that will connect to the 5G network and then connect to other devices over Wi-Fi technology. Finally, there will be 5G fixed-wireless access (FWA) devices, with antennas permanently mounted on buildings or in windows, providing a home or business with broadband in place of a wired connection.

All of these 5G devices will operate over traditional and new cellular radio frequency bands in the low- (sub-1 GHz, such as 700 MHz), mid- (1–6 GHz, such as around 3.5-3.8 GHz), and millimeter-wave (mmWave, such as 28 GHz) ranges. While smartphones, modems, and hotspots will mostly use low- and mid-range frequencies, 5G FWA devices will often operate using mmWave technology,2 which offers the potential for higher bandwidth than sub-6 GHz frequencies. Because mmWave frequencies struggle to penetrate walls or pass through certain types of glass, many 5G FWA devices will require mounting antennas on windows or a building’s exterior wall.

5G smartphones. Making a 5G-ready handset is more complicated than one might think due to differences in two critical components of a 5G versus a 4G phone: the radio modem and the antenna. The modem in a smartphone usually sits on the same chip as the processor. A bundled 4G chip for a high-end phone cost an estimated US$70 in 2018;3 the 5G version will almost certainly cost more. A leading modem/processor manufacturer has announced that its 5G chipset will be ready in 2019,4 although supply constraints suggest that wide availability will not occur until the second half of the year.5

The bigger challenge is designing an antenna for 5G. Since the new radio technology will launch both at frequencies around 28 GHz (which require narrow-beam, high-gain antenna systems made up of multiple combined radiators) and at frequencies below 6 GHz (for which single-element, low-gain, omnidirectional antennas can be used), the design of a 5G antenna is much more complicated than that for a 4G antenna.6 The antennas and front end of a leading-edge 4G smartphone typically cost around US$20 in 2018, and 5G solutions, expected to be available in 2019, will almost certainly carry a higher price—possibly much higher.

Putting these factors together, a 5G-ready phone’s component costs in 2019 will likely be US$40–50 higher than for a comparable 4G phone—for a phone with relatively few networks worldwide to connect to, and likely with only narrow coverage even where available. There’s one good piece of news, however: Battery life will likely be a smaller issue than it was when 4G was launched. Chipmakers have said that they expect battery life for the first 5G phones to be more or less in line with that of current 4G handsets.7

5G modems/hotspots. The first 4G network was activated in December 2009. From 2010 through 2012, retailers sold tens of millions of 4G modems/hotspots, generating hundreds of millions of dollars of revenue for both the device makers and the operators charging wireless subscription fees.8 These small devices, about the size of a hockey puck, sold for US$200–300 each at first but rapidly dropped to under US$100.9 They were portable, and people used them to connect phones, computers, tablets, and other devices to the internet. But their sales began to decline as more and more 4G handsets entered the market, particularly as users were able to use later-model smartphones as 4G hotspots to wirelessly tether other devices to their phones instead of needing standalone modems.

We expect the 5G equivalent of the 4G modem/hotspot to be approximately as successful, bridging the gap between when 5G networks are turned on and when 5G handsets become widely available and affordable for casual users. The two largest American carriers have already publicly discussed selling modems before mobile handsets,10 and one major chip manufacturer’s new 5G chipset is so large that it is unlikely to fit in a smartphone but can easily be used for modems.11 Since modems consist of just a radio, antennas, and a battery, they cost much less than smartphones, with no need for a screen (usually a phone’s most expensive component), camera, or sleek body. Thus, although handsets will rapidly overtake them in the first year or two following launch, modems will likely be an important part of the nascent 5G market. It should be noted that although the signal to the modem will be on 5G, the signal from the puck to the devices it connects (smartphone, PC, etc.) will be over Wi-Fi or other local-area wireless technology, which means that speeds could be degraded depending on the technology.

5G FWA devices. As discussed above, a small antenna about the size of a hardcover book can be placed on the inside or outside of a home or business window that has an unobstructed line of sight to a 5G mmWave transmitter not more than about 200–500 meters away. (That mmWave transmitter will usually be located on a commonplace utility pole, not an expensive special-purpose tower, and will likely use multiple bands, both mmWave and sub-6GHz.) If that transmitter is connected to a high-speed fiber network, the subscriber will enjoy speeds of hundreds of Mbps, with possible peaks of gigabits per second. The antenna will connect or be attached to a modem/router that distributes the high-speed signal inside the home or business over Wi-Fi, connecting smartphones that otherwise would not achieve 5G speeds, as well as computers, tablets, smart TVs, and other connected devices.

Some American carriers have already begun their 5G launch on a limited basis in a few cities using both mmWave and traditional frequencies.12 There have also been many non-US trials of 5G FWA devices using mmWave; however, at this time, the only firm outside the United States that is definitely planning a 2019 launch is an Australian operator.13

Note that the markets for both 5G modems/hotspots and 5G FWA devices are about providing wireless connectivity as an alternative to traditional home broadband, rather than providing an alternative to 4G for mobility. In the long term, the 5G mobile market (for handsets, Internet of Things devices, and connected vehicles) will likely be measured in terms of billions of connections, but in 2019, most 5G customers will likely use 5G as an alternative to wireline, not as a replacement for 4G. Used in this way, the applicability of 5G FWA over mmWave varies considerably by country. In places where fiber-to-the-home or other high-speed internet service is ubiquitous and affordable, FWA does not always deliver a particular advantage (although there may be some situations in which 5G FWA offers higher speeds and/or capacities than some fiber solutions). It is in places where wireline is less widely available and/or more expensive, or where wireless capacity in the traditional cellular radio bands is already congested, that mmWave solutions will likely be more useful.

Indeed, many internet users worldwide already rely on cellular wireless data for 100 percent of their home data needs. According to a 2017 Deloitte survey, that percentage is very low in some countries (such as the United Kingdom, at 5 percent). But in other countries (such as the United States, Canada, and Turkey), nearly one-fifth or even more of the internet-using population relies on cellular radio waves instead of wires (figure 1).14 It is worth noting that there can be a form of digital divide between wired and wireless-only users, with those resorting to the latter option sometimes experiencing lower speeds and/or capacity. The two user groups are also demographically different: Wireless-only consumers in each of the countries studied differ in age, income, education, and other factors.15

When it comes to reaching the broadest possible customer base in a country where both wireless and wired connections make sense in different geographies, 5G wireless (at both sub-6 GHz and mmWave frequencies) can be useful when combined with a wireline fiber strategy. In Canada, two of the country’s three major operators have announced such a hybrid strategy, using FTTP for homes where fiber density is high enough, and 5G to cover the rest. One carrier plans to enable 9 million of its 12 million subscriptions with FTTP and sees an “immediate opportunity” to reach another 0.8–1 million using 5G wireless technology.16

Wireless adoption through the generations: It always looks like this

To some, our predictions for 5G adoption might seem unusually conservative or pessimistic. But we see no reason to doubt that the first years of 5G will look almost exactly like the first years of 4G (2009–10). At that, 5G usage will spread faster than 3G, which launched in 1998 and took time to gain widespread acceptance.17

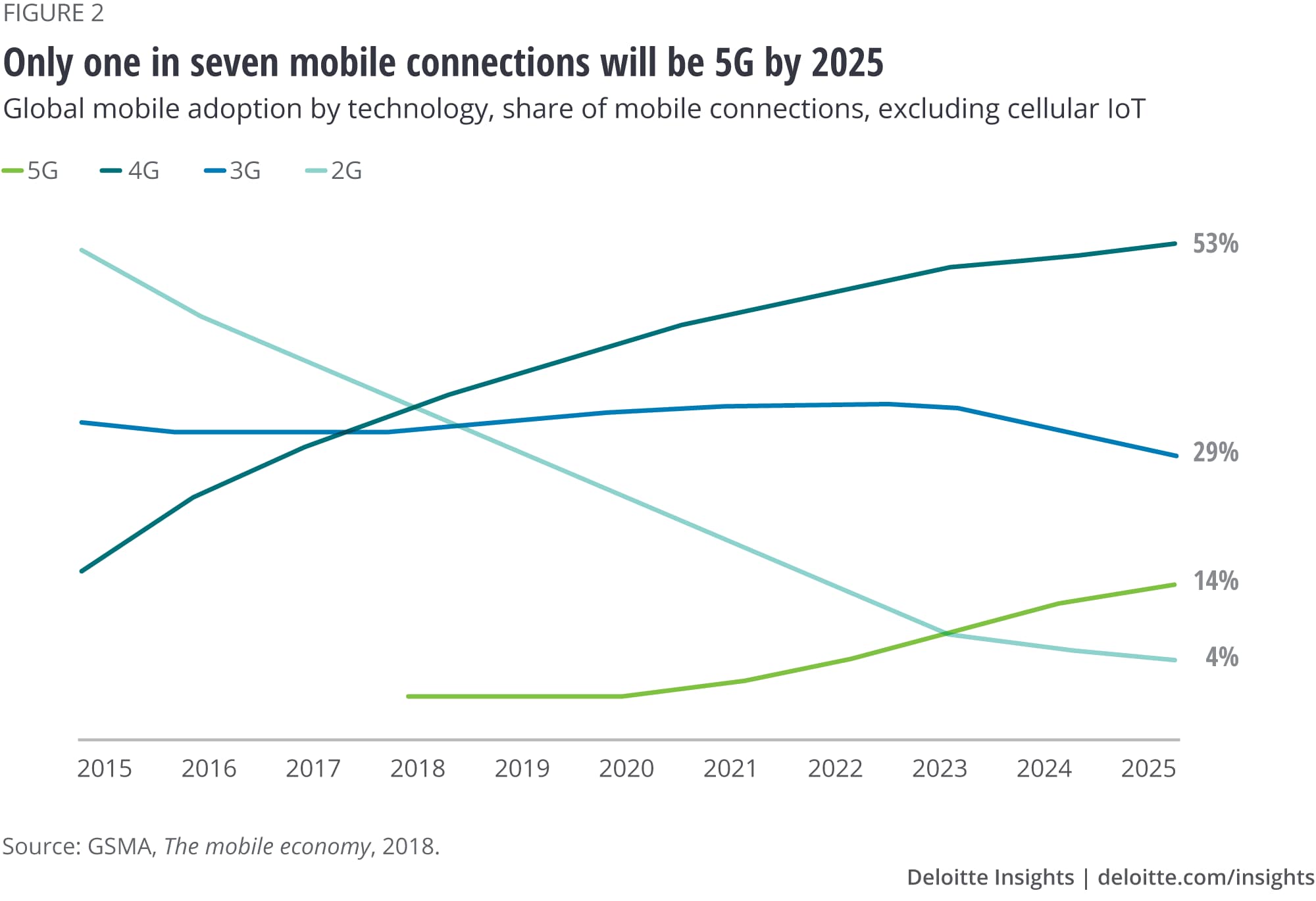

4G launched in late 2009 and early 2010 with only a handful of operators offering services within a limited territory.18 Although more and more 4G networks have deployed in the decade since then, it will take until 2019 for 4G to become the single-most used wireless technology worldwide, and according to the GSMA, 4G usage will not surpass 50 percent of all subscribers globally until 2023—14 years after launch.19 This means that 5G will likely still be a relatively niche technology even in 2025, with its forecast 1.2 billion connections making up only 14 percent of the total number of mobile non-IoT connections worldwide (figure 2). Considerable variance will be seen across countries: 49 percent of all American subscribers are expected to be 5G in that year, 45 percent in Japan, 31 percent in Europe, and 25 percent in China, but only single-digit percentages in Latin America, Middle East, and Africa.20 Ten years from now, providers will still be rolling out 5G.

The need for speed: Ideal vs. real-world conditions

New wireless technologies always offer faster speeds, but speed can mean at least three different things: speeds achieved in the lab or in limited trials, peak speeds achieved in the real world under ideal conditions, and the speeds that real users in the real world achieve on average. Although 5G is still in its early days, there is some data indicating what each measure is likely to be.

The fastest-ever 5G lab transmission has been 1 terabit per second,21 and the record for a field trial currently stands at 35 Gbps.22 Neither is a good indicator of real-world speeds in the short term, although longer-term projections are that 20 Gbps may be an achievable real-world peak speed.

5G under real-world conditions will likely be slower than 35 Gbps but still markedly faster than 4G networks—and also faster than some fiber and cable solutions. In general, peak speeds of more than 1 Gbps are likely, although that would only be for someone ideally situated, very close to the transmitter, and using the network when it was not busy. Nonetheless, according to simulations, median data speeds would surge with the upgrade to 5G, based on the cell-site locations and spectrum allocations of two current networks. One simulation based on a Frankfurt-based network estimated a ninefold increase in median speed, from 56 Mbps to 490 Mbps.23 Another test based on a San Francisco network calculated a 20-fold increase, from 71 Mbps for a median 4G user to 1.4 Gbps for a median 5G user if using mmWave coverage.24 As with real estate, achieved 5G speeds will come down to location, location, and location!

Speed is not the only benefit of 5G networks, of course. Another additional potential benefit is lower latency: the time it takes to send a message from a device to the network and get the answer back. 4G networks average latencies of around 60 milliseconds (ms),25 although there can be considerable variation, and 4G latencies could theoretically be lower than that. But 5G networks will have, in time, a latency of less than 1 ms.26 Even in 2019, 5G will have lower latency than that of the average 4G network—and although 5G’s average latency may not be much lower than that of 4G, the worst-case latency will likely be much better. In 5G field trials, real-world latency has been “as low as 9 ms,”27 although it is unclear what the average latency will be on the commercial networks that expect to launch in 2019; 20–30 ms seems like a plausible figure.

For the average consumer or enterprise user, and for most current real-world applications, there is little practical difference between one-tenth of a second and one-fiftieth of a second (100 ms and 20 ms, respectively). Over time, however, ultralow latency may matter a great deal for IoT-enabled applications,28 autonomous vehicles,29 and performing remote surgery with haptic feedback,30 even though these applications are more likely to materialize in 2021 and beyond rather than in the next two years, and will require both ultralow latency and ultrareliable networks with guaranteed reliability.

Bottom line

So far, this chapter has largely focused on the aspects of 5G that are likely of most interest to 5G network users (whether enterprise or consumer). Here, we focus more on the concerns that are likely more relevant for network operators.

The predictions at the top of this chapter relate to only true 5G networks and devices, excluding those operators who will almost certainly market the very latest 4G LTE (long-term evolution) technology, often referred to as 4.5G, as 5G.31 To users, the distinction may not matter at first: Both 4.5G and 5G networks offer very high speeds of hundreds of megabits per second, or even gigabits per second. However, there is an important difference for the operator—namely, cost. If operators can deliver 500 Mbps wireless service over 4.5G, why should they bother to spend tens of billions of dollars on capital expenditures (capex) for equipment and radio spectrum to enable 5G globally?

There actually is a nonflippant answer to this question, and it has to do with 5G’s greater capacity. Through various technologies, 5G is expected to provide a hundredfold increase in traffic capacity and network efficiency over 4G.32 This may not matter to all operators: A third- or fourth-rank player with a lot of spectrum but relatively few customers may well be able to offer 5G-like speeds on a less efficient 4G network. But for the leading operators in many countries—such as the United States, the Philippines, France, Ireland, Australia, and the United Kingdom, where networks are running at higher capacity than in some other countries33—the ability to offer higher speeds, more-uniform high speeds, and greater overall capacity per month can be achieved only by moving to 5G.

Speaking of capex, the picture for 5G looks better for operators than was first thought. One study predicted that, to enable 5G, operator capex spending would need to rise from 13 percent to 22 percent of revenue for only a limited rollout.34 But as 2018’s field trials progressed, many operators in North America, Europe, and Japan are reevaluating the cost, and releasing public guidance that capex intensity for 5G will be more or less flat with their 4G spending.35 One major reason for this is that they have “pre-loaded” spending by aggressively investing in denser fiber networks (both in anticipation of 5G in the future and to support 4.5G technology today), as well as by purchasing 5G-ready radio hardware that can be upgraded to full 5G with software upgrades when the time for launch comes.36

All of the above, it should be noted, applies only to capex—one-time investments. It is unclear what impact 5G might have on annual operating expenses.

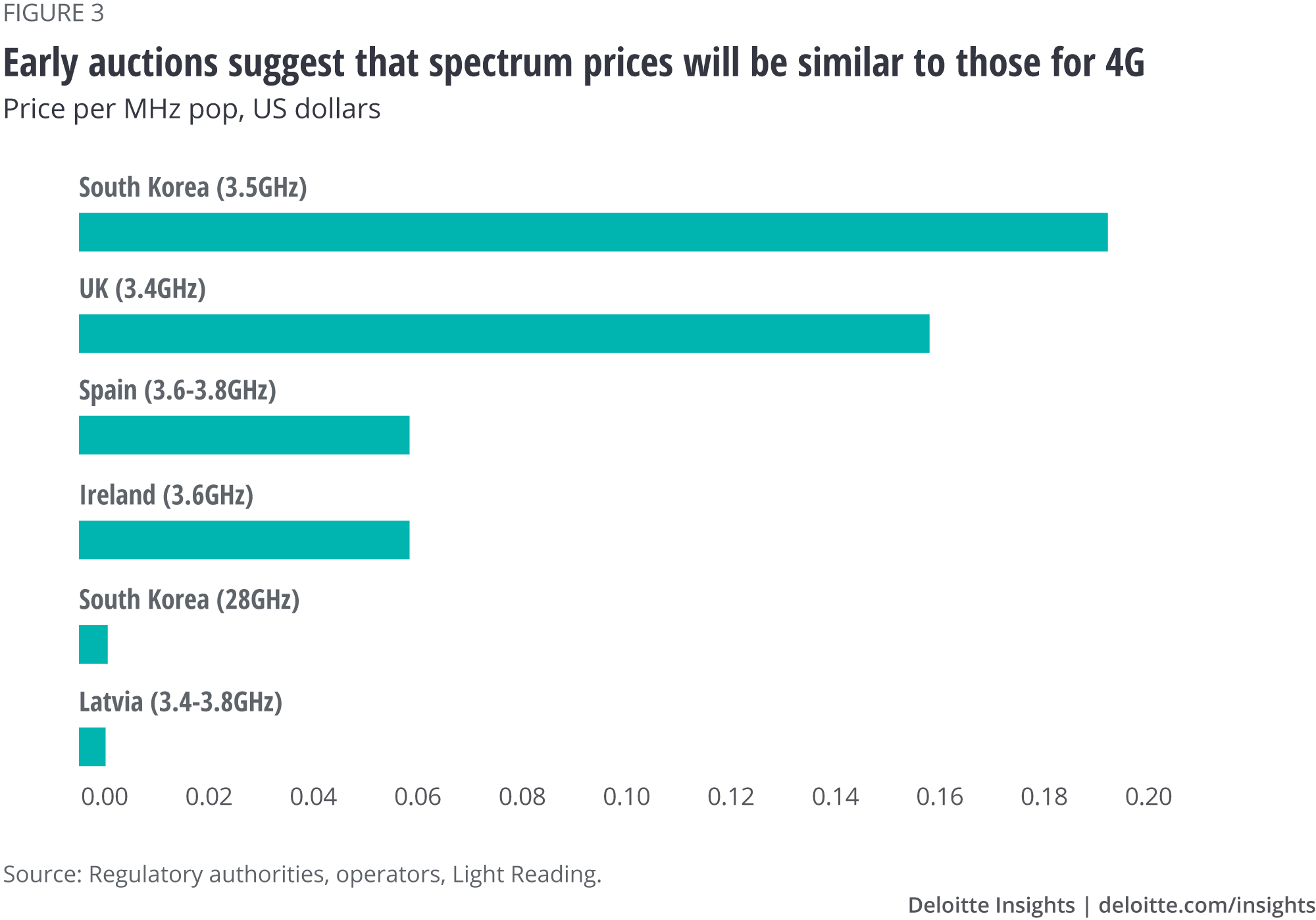

As far as spectrum goes, early signs are that operators’ spectrum costs will be closer to the 4G experience than the 3G (see figure 3). For the launch of 3G, network operators spent heavily on spectrum: As measured in price per MHz per person (MHz pop), the United Kingdom’s 3G spectrum auctions sold frequencies for an average of US$3.50 MHz pop. In spectrum auctions prior to 4G’s rollout, however, operators spent much less, with 800 MHz spectrum going for US$0.60 MHz pop, and spectrum in the 2.6 GHz bands garnering only US$0.07 MHz pop. (It is important to note that the exact bands matter a lot to price: Lower frequencies travel further and better penetrate buildings, and are spectrum’s equivalent of beachfront properties. Hence, the higher the frequency, the lower—usually—the MHz pop.) Based on some early auctions, the prices for 5G spectrum, depending on the frequency band, are consistent with those for 4G spectrum: All auctions in the six countries in figure 3 have been for less than US$0.20 MHz pop, and two were under a penny.37

However, spectrum prices have not been so uniformly low in all geographies. The Italian spectrum auction that concluded in October 2018 saw higher prices, with 700 MHz spectrum commanding a robust US$0.65 MHz pop, and the mid-band 3.6–3.8 GHz frequencies priced at more than US$0.42 MHz pop—much higher than expected (more than double, in fact) for the Italian market. Going forward, if the Italian experience is more typical, operators may need to adjust their expectations upward, at least a little, for how much they will have to pay for non-mmWave spectrum. At this time, no one appears to be paying a premium for mmWave frequencies: Even the Italian auction is pricing them at less than 1 percent of the MHz pop of the mid-band spectrum.38

Make no mistake: 5G is the connectivity technology of the future. Although its adoption curve may be relatively shallow in the next 12 to 24 months, and it will likely take years for 5G to replicate 4G’s marketplace dominance, many telecommunications operators have a strong incentive to jump on the 5G bandwagon for reasons of speed, latency, penetration, and (especially) capacity. When that happens, it should be a much faster world.

Explore the collection

-

Quantum computers: The next supercomputers, but not the next laptops Article6 years ago

-

Radio: Revenue, reach, and resilience Article6 years ago

-

Does TV sports have a future? Bet on it Article6 years ago

-

3D printing growth accelerates again Article6 years ago

-

5G: The new network arrives Article6 years ago