What’s holding organizations back? According to the skills-based organization survey, the top challenge/obstacle is legacy mindsets and practices, cited by 46% of business and HR executives as one of the top three obstacles to transforming into a skills-based organization. Technology is not the issue; only 18% cite lack of effective skills-related technology as a top three obstacle, the lowest of the 10 obstacles listed.6

The new fundamentals

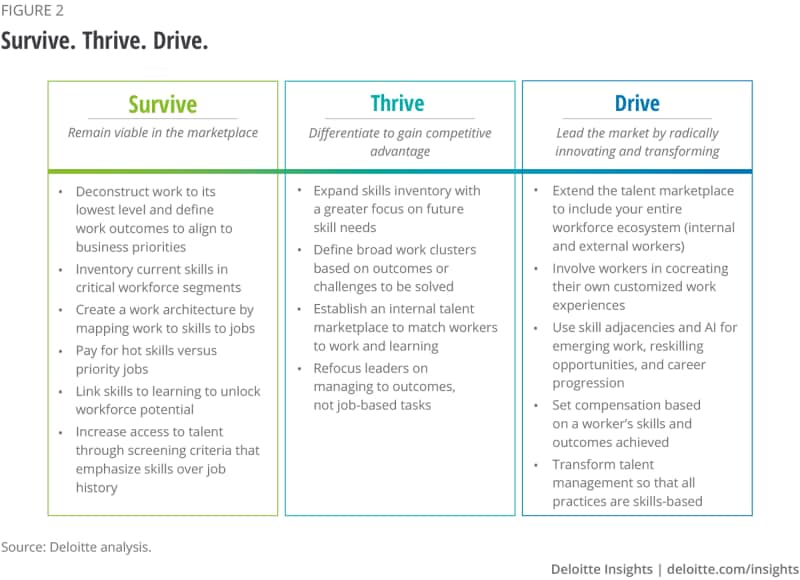

Define work based on the skills required. Instead of defining work as a specific set of tasks and responsibilities (i.e., a job), define work primarily based on the skills it requires. Organizations will need to first consider their strategic objectives or desired outcomes, then identify the work that needs to be done to achieve them and the skills required to do that work.

Collect and analyze data about worker skills. Thanks to recent technology advances in skills assessments, skills inferencing, analytics powered by artificial intelligence (AI), and live “tryouts” for evaluating external candidates, organizations have access to a differentiated level of work skill data. Similar technology can be used to inventory the skills of existing workers, supplemented with more holistic data about workers’ interests, values, work preferences, and more.

Collecting data about workers can be controversial, as discussed in our “Negotiating worker data” chapter. However, in the context of skills, our research suggests workers are more open to having this data collected. Eight in 10 workers are willing to have their organization collect data about their demonstrated skills and capabilities and seven in 10 are willing to have data collected about their potential abilities. This even extends to using AI to passively mine worker data as they work, with 53% of workers seeing this as positive.7

View workers based on their skills, not job titles. Instead of viewing workers narrowly as job holders performing predefined tasks, view them holistically as unique individuals with a portfolio of skills to offer—and then match them with work that aligns with those skills. The work might be performed by an individual, a team, or a shifting set of resources, each person contributing their appropriate skills (while improving their current skills and developing new ones), then moving on to other work when their particular skills are no longer needed. As part of the deployment process, it’s ideal to match workers with work that aligns not only with their skills, but also with their unique interests, values, passions, development goals, location preferences, and more—since people are happiest and most productive when doing work that fits who they are and what they care about. Doing so will help workers maximize their personal contributions and growth. It will also help create a more equitable and human-centric worker experience, creating value for workers and society at large.

Make decisions about workers based on skills. Beyond matching workers to work based on skills, organizations will want to make skills the focal point for all workforce practices throughout the talent life cycle—from hiring to careers to performance management to rewards—placing more emphasis on skills and less on jobs. For example, in hiring, that means evaluating candidates based on skills and capabilities rather than degrees and certifications. More than one in three respondents to the Deloitte 2023 Global Human Capital Trends survey state that they are not using skills to help their workforce meet their fullest potential, highlighting an opportunity to embed skills throughout the talent life cycle.