Balancing worker autonomy and choice with organizational needs

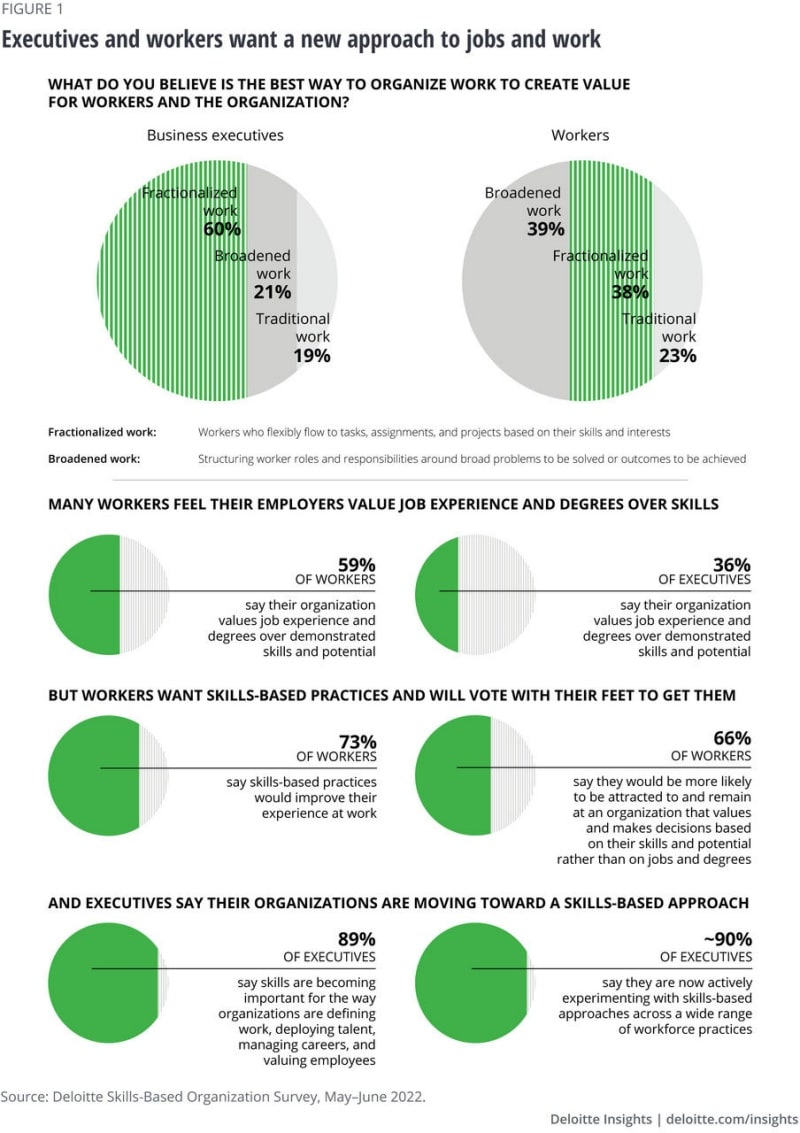

If work is unbound from jobs, and workers are given more opportunities to exercise choice and autonomy in how they apply their skills, what happens if the work workers want to do no longer aligns with the work that organization needs them to do?

The rise of internal talent marketplaces so far has been primarily based on workers exercising discretion as to which projects and tasks in addition to their “day job” they want to take on, once they negotiate with the manager offering the work. Rarely is a person’s performance on this type of work ever formally evaluated, recognized, or rewarded; only 15% of business and HR executives say they capture this data.

If work becomes completely fractionalized into projects and tasks, will some organizations decide to match workers’ skills without the workers’ agreement, either via algorithms or at the discretion of managers? Surprisingly, 54% of workers say this would be a positive development—perhaps because they would prefer this to being confined to a job entirely—yet only 33% of business and HR executives agree.

Organizations will need to be careful that work doesn’t get parceled out only in a top-down or mechanistic fashion, driven by opaque and potentially biased algorithms. Leaders seem ready to cede this type of control: 70% of business and HR executives say providing workers with more autonomy, agency, and choice in the work to which they apply their skills, with subsequent less centralized control by the organization, would be a positive development, and only 4% say it would be a negative one. Ceding control like this can yield big gains in innovation and growth (think of Google’s engineers who developed Gmail in their 20% time allotted to letting them apply their skills to solving problems they think are worth tackling),26 but, as with most organizational transformations, it’s a massive culture shift that will require ongoing effort.

Taking the first steps toward the skills-based organization

In our experience working with organizations embarking on this journey, they typically take one of three different approaches.

1. Often, they’ll start with a particular talent practice and transform it to be based more on skills and less on jobs, and then continue to either similarly transform another practice or determine that they have to create a skills “hub” before realizing the transformation.

For example, Cargill started by transforming learning and development to be based more on skills, and less on suggesting learning and development opportunities based on people’s jobs. As it proceeded to also adopt skills-based hiring and a skills-based talent marketplace, it realized it had core skills hub work to do to realize the vision; so it embarked on an initiative to develop an enterprisewide skills framework, using skills as a unit of measurement to better acquire, manage, and develop its people going forward.27

2. Others start with creating a centralized “skills hub” before expanding out to skills-based talent practices. To do this, they often start by inventorying or creating a language for skills or developing a skills-based talent philosophy.

One life sciences organization focused on designing a skills-based organizational philosophy and value proposition, and then developed a skill-mapping playbook that enabled it to tag its skills ontology and proficiency levels to learning objects. This enabled the organization to start on transforming learning with a skills-based approach, with an ultimate goal of creating more personalized development opportunities for its employees. It also identified the “hot” skills (skills in high demand but short supply) upon which to focus its efforts. Ultimately, the organization hopes to incorporate skills into many aspects of the talent life cycle in the future, from talent sourcing to compensation.28

3. The third archetypal journey is to start with the work, either with an internal talent marketplace that lets some work live as projects and tasks outside of the job, or as broadened jobs.

Trane (formerly Ingersoll Rand) started with broadening the job: doing away with highly specialized jobs spread across 28 distinct job grades, and instead creating broader job “clusters” that share similar broadly defined work responsibilities and outcomes, spread across seven job grades, and narrowed down to only 800 job titles with a set of skills for each job. This allowed the organization to effectively build a skills-based development and career strategy, enabling employees to assess their career goals and current skills, find a future role, and create a development plan for growth. Using the platform Fuel50, the company now has a career assessment, matching, and development system—which the organization believes has increased employee engagement and retention by double digits.29

Whatever the archetypal journey chosen, the following practices can help organizations:

- Think evolution, not revolution. Dismantling the paradigms and practices of jobs we’ve lived with for over a century is best thought of as a long-lasting evolution, not a revolution. Few organizations will be willing to abandon jobs and hierarchies entirely. But there might be certain spots in your organization where doing so, either fully or partially, will yield significant benefits. Consider places where skills are changing so fast that talent practices can’t keep pace, where you could use diverse thinking and skill sets to solve problems or to innovate, or where you’re spending time determining what automation or humans should do but never seem to be done. Most organizations start small and build out from there, with the majority starting with transformation of a single talent practice rather than starting with the bigger challenge of reorganizing work beyond the job.

- Always lead with the why. Explains Cargill’s Julie Dervin, “Start by defining the why, which is your value proposition and your business case to support this multiyear journey. It involves a lot of change at a very systemic level in people processes and the way things are done.” For Cargill, this “why” included the ability to:

- Create greater speed and agility, including speed to market

- Better respond to customers with the right skills accessible when the business needs them

- Provide more opportunities for workers to grow through unique career experiences by applying their skills to different areas within Cargill

- Reduce variable costs by letting employees take on new projects and tasks instead of paying contractors or off-balance-sheet talent

- Better utilize the workforce by unlocking untapped capacity30

- Find your pain point or lowest-hanging fruit. When starting with a skills-based practice, pick an area where the business case is the biggest, based on your organization’s specific needs and pain points. Many organizations, for example, are now emphasizing the value of skills, not just degrees or experience, when hiring—both in response to a tight labor market, and to improve equity, diversity and workplace culture.31 Alternatively, start with those practices that have the clearest connection with skills today, such as learning and development or talent acquisition, or that can use mature technologies easily available as upgrades to existing HR information systems such as talent marketplaces.

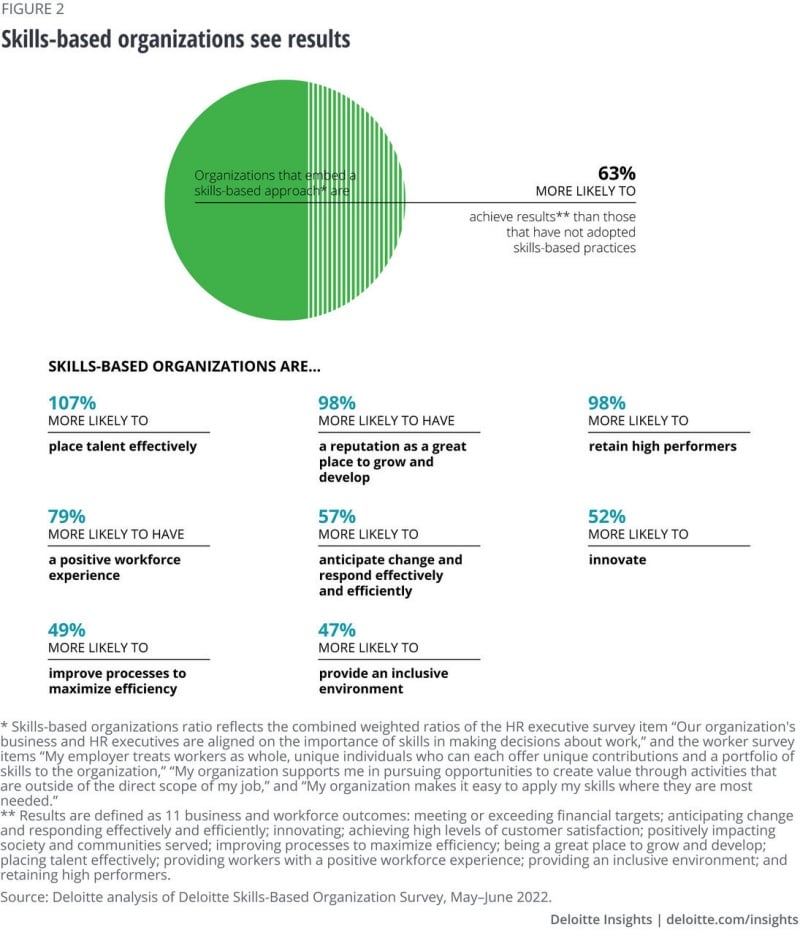

For most organizations, the notion of the job won’t go away entirely. Instead of being the only way to organize work and make decisions about workers, it will become just one of many ways, giving leaders the option to use a variety of approaches. By moving to a skills-based approach, leading organizations can pivot from a traditional model aimed at scalable efficiency that grew out of our industrial past to one that is far more suited to a world in which speed, agility, and innovation rule the day, and in which people expect more meaning, choice, growth, and autonomy at work.