New payment models in medtech Regulatory, technology, and marketplace trends converging to create new opportunities for manufacturers

21 minute read

02 March 2020

Jay Zhu United States

Jay Zhu United States- Christopher Park United States

Leena Gupta United States

Leena Gupta United States Debanshu Mukherjee United States

Debanshu Mukherjee United States

Medtech manufacturers are rising to the challenge to deliver value through new payment models. To be successful, they will likely need to identify the right customers, construct the right contract, implement a new go-to-market model, and navigate regulatory constraints.

Executive summary

Health care organizations, under pressure from the government and private payers to demonstrate value (improve clinical outcomes and patient experience) while controlling costs, are in turn putting pressure on medtech manufacturers to differentiate themselves and deliver higher value. This is an opportunity for medtech manufacturers to propose new forms of contracting and partnerships, ranging from aspects of product performance to risk sharing.

Learn more

Explore the Life sciences collection

Learn about Deloitte's services

Go straight to smart. Get the Deloitte Insights app

Many medtech manufacturers are rising to the challenge and creating interesting new contracting and value arrangements, such as sharing risk with providers for total cost of care or clinical outcomes. Health systems and health plans are also interested in the shared-risk models if regulatory hurdles can be surmounted and if the value proposition is strong enough. Industry experts we interviewed for this study agreed that data systems, regulatory considerations, and other changes are aligning to create new opportunities, but all parties identify regulatory and government payment systems, data, and lack of quality measures as barriers.

As forward-thinking companies develop the required capabilities in their products, value propositions, and go-to-market approaches, they should track and measure outcomes. They should identify the right customers, select appropriate outcomes, construct the right contract, implement a new go-to-market model, navigate regulatory constraints, and build new capabilities, including data and analytics. Companies also should understand what the customer values—a critical first step—and then select customers and partners based on the company’s ability to deliver on value as they define it. This report provides insights on all these elements of new payment strategies.

Our research

The Deloitte Center for Health Solutions interviewed US and global medtech manufacturers, health systems, health plans, and former government officials as well as Deloitte professionals during fall 2019. In addition, we led a workshop with technology companies and health system supply chain experts to discuss these issues as well as learn about their experiences with these models to date.

Many trends are making the time ripe to develop new payment arrangements

Medtech manufacturers are facing marketplace pressures

Globally, governments, employers, and individuals are raising concerns about health care costs and challenging health care stakeholders to show value; global health care spending is expected to rise to about US$10 trillion by 2022.1 In the United States, hospitals—the major purchasers of medical technologies—are under financial pressure themselves as government programs’ share of revenues rise. Medicare and Medicaid tend to pay less than other payers and increase payment rates slowly, even while costs continue to increase.

In response, many hospitals are consolidating and using their greater purchasing power to drive harder bargains with medtech manufacturers. Value committees are often driving decisions about what is purchased for the hospital, including being more selective about which technologies they choose. New regulations will require hospitals to publish the prices for services they provide, starting in 2021, which may heighten interest in finding ways to lower costs. Collectively, a focus on costs and pressure to demonstrate value has contributed to intensified competition and the potential for medical technology to be seen as a commodity where price rules.

Care delivery is being transformed

With increasing cost of care, health plans and government program payment policies are supporting delivery of care away from the traditional hospital settings, and many see the future of health care in wellness and prevention.2 When care moves from inpatient to outpatient settings, payment rates can be lower,3 which can exacerbate financial payment pressures for medtech manufacturers. Our forthcoming report found hospital outpatient spending to be 48 percent of hospitals’ total revenues in 2018, having grown from 37 percent in 2007.

Technology is advancing rapidly

As discussed in our recent article Winning in the future of medtech, technology companies continue to disrupt health care with innovative products aimed at bridging the disconnect between providers and patients and improving overall outcomes. Other technology capabilities such as remote patient monitoring and telemedicine, as well as the increasing use of big data and AI, are also changing the face of health care.

Value-based care is on the rise

In the United States, purchasers are trying to control spending and improve outcomes by encouraging hospitals and large physician groups to take on more financial risk for patient outcomes and total cost of care. The US Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) regularly announce new payment models that require providers (hospitals or physician groups) to take on risk, and is revising existing programs to require providers to take even greater risk. Value-based purchasing for hospitals is also driving interest in ways to improve outcomes and patient experience and to reduce readmissions.

In a recent Modern Healthcare article, CMS administrator Seema Verma said: “Value-based payment under the Trump administration is the future. So, make no mistake—if your business model is focused merely on increasing volume rather than improving health outcomes, coordinating care, and cutting waste, you will not succeed under the new paradigm.”4

Employers and health plans are committed to have most of their contracts based on outcomes and sharing risk with provider organizations and implementing strategies accordingly. Health plans such as Aetna, Anthem, and UnitedHealthcare have entered into new partnerships, including payment models with health systems. They have also entered into risk-based contracts with drug companies and population health vendors.5

Globally, many governments are developing their own value-based initiatives. They are focused on developing and using value measures and frameworks, including through tenders. For example, the European network for health technology assessment (EUnetHTA) has been set up with the goal to enable HTA bodies across Europe to harmonize health technology assessment.6 Many countries have some form of a national disease registry to track patient outcomes.7 In the European Union, coverage with evidence development is commonly used for medtech risk-sharing agreements. As more data sources become available, organizations such as the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) continue to use them and create frameworks for evaluating value and evidence to cover therapies and technologies.8

In response, some medtech manufacturers are considering how to shift from selling products to outcomes, which naturally moves the contract from product/volume-based to outcome-based and positions them well for new payment arrangements.

Policy and regulations influence payment models

In general, government sets payment for many items and services and has a strong influence on the incentives in the medtech market through policy and regulations. Medicare, Medicaid, and health plans pay the hospital for a bundle of services that includes medical technology; technology could be a small or large part of the cost of care for that bundle. Even though these payers are driving value-based care, they are not necessarily open to developing separate payments for technology and are instead leaving it to health systems to arrange for payments with medtech manufacturers. Special payments for innovative new technologies do exist.

The Medicare and Medicaid programs feature several laws that were established to govern incentives in the system that can generate excessive and even fraudulent revenue under fee-for-service payment. These rules limit hospitals and physicians from offering incentive payments—even if the incentives reward better value in today’s new systems. Industry stakeholders have been calling for changes to these policies to allow value-based contracts to go into place, and the federal government recently issued two proposed rules in response (see sidebar, “Proposed changes that will allow value-based contracts to go into place").

Proposed changes that will allow value-based contracts to go into place

Physician Self-Referral Law (Stark Law)9: This law was established to prevent physicians from generating revenue by referring patients to entities in which they have a financial interest. The law calls for compensation to be set in advance, at fair market value, and not take into account the volume or value of a physician’s referrals or the other business generated between the parties.

This might inhibit value-based contracts if the payment model gives physicians more money for reducing unnecessary care. Many shared savings payments do take into account the volume or value of referrals for hospital services and other designated health services—not, as was the concern that led to the law, by increasing spending but by paying more of the shared savings payment if volume or total cost of care goes down.

The proposed rules would create an exception to the physician self-referral laws for value-based arrangements, and include a definition of the purpose of these arrangements:

Value-based purpose means:

(1) Coordinating and managing the care of a target patient population;

(2) Improving the quality of care for a target patient population;

(3) Appropriately reducing the costs to, or growth in expenditures of, payers without reducing the quality of care for a target patient population; or

(4) Transitioning from health care delivery and payment mechanisms based on the volume of items and services provided to mechanisms based on the quality of care and control of costs of care for a target patient population.

Anti-Kickback Statute:

In coordination with CMS’s proposed rules on self-referral, the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Office of the Inspector General (OIG) proposed rules creating safe harbors for the anti-kickback regulations, which allows the government to charge entities with criminal penalties if it finds they have knowingly and willfully offered, paid, solicited, or received remuneration to induce or reward the referral of business under Federal health care programs.

Despite the coordination between the agencies around permissible activity, value-based, and other arrangements, the OIG notes that “arrangements that might be protected by a physician self-referral law exception, but might not be explicitly protected by an Anti-Kickback Statute safe harbor, would not necessarily be unlawful under the Anti-Kickback Statute. They would need to be examined on a case-by-case basis, including with respect to the intent of the parties.”

Medtech manufacturers are taking on risk for clinical outcomes

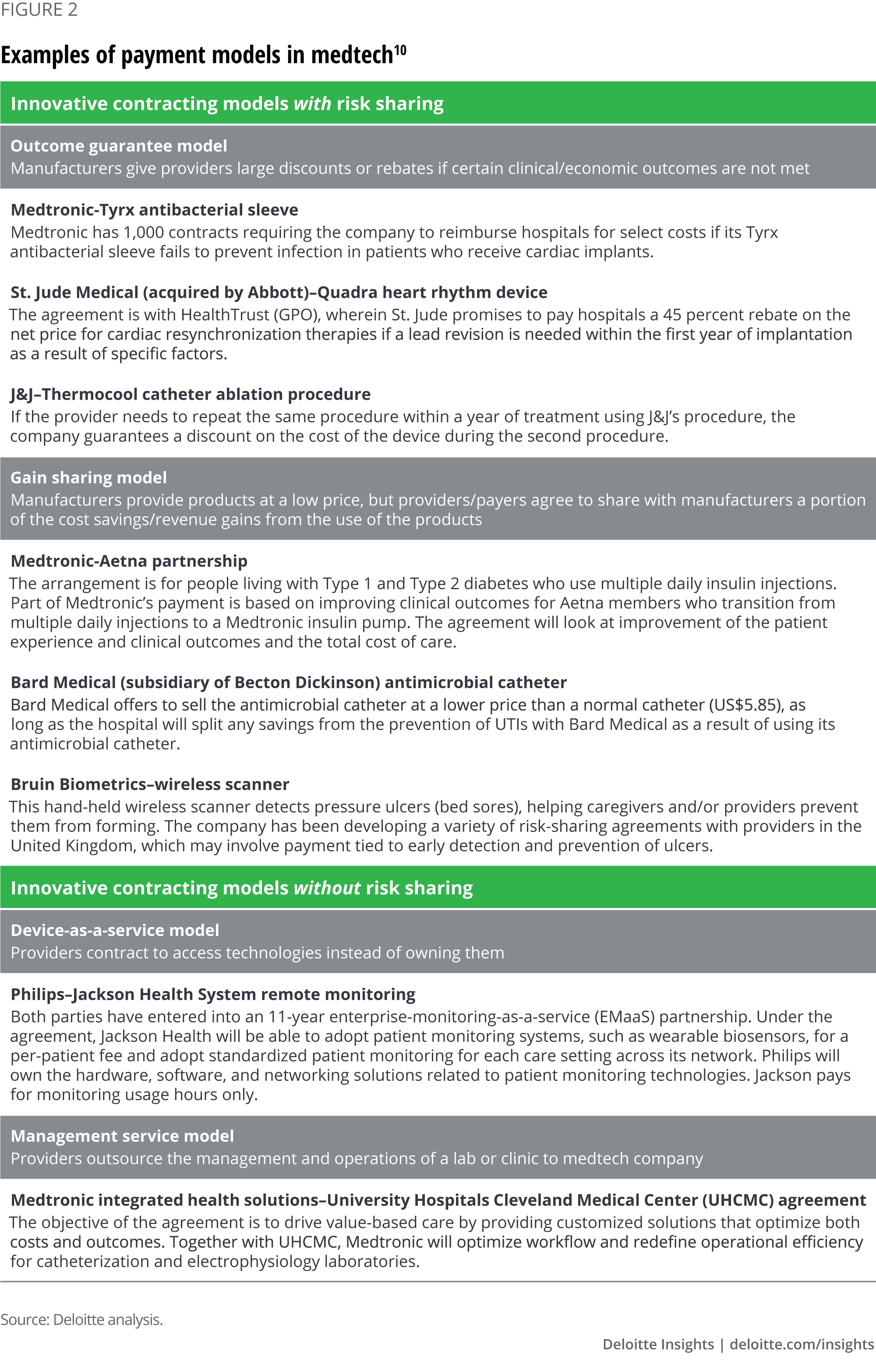

Our interviews with industry experts and extensive review of secondary sources yielded examples of payment arrangements where medtech manufacturers take risk for clinical outcomes and others where risk is not part of the payment model. Even more such arrangements might be in the negotiation stage (figure 2). In this paper, we refer to both payments from Medicare or a health plan and contracting between manufacturers and health systems as payment models.

The value proposition for payment innovation

In general, all parties—providers, payers, and medtech manufacturers—stand to benefit from innovation in payment models. For both providers and payers, one benefit of entering into value-based contracts is shifting some of the financial risk to medtech manufacturers. Providers can gain access to manufacturer resources to optimize care delivery and operations. With aligned incentives, we expect higher overall care quality, better patient experience, and, ideally, lower cost of care, all of which benefit payers and patients and can help providers succeed under their own value-based care contracts. Additionally, contracts can enable providers to have a holistic and long-term approach rather than the traditional procedure-focused approach.

From the standpoint of a medtech manufacturer, the benefits of entering into a value-based contract arrangement are many:

- Creating meaningful product differentiation

- Improving access to and overall use of nonreimbursable products

- Offering protection from price erosion

- Increasing the barrier to switching to another product or vendor and creating a stickier relationship with customers

- Increasing market share and revenue by becoming a preferred product

Of course, a product should demonstrate value in the arrangement and the financial risk should be reasonable from both parties’ point of view. Interviewees expressed interest in getting outside their comfort zone with respect to taking on risk to gain experience with such models. Depending on the type of technology, partnerships could be forged with providers for procedure- or service-related products or with payers for products that show value in chronic disease management or prevention. Physicians and patients can benefit from earlier access to and the use of higher-value technologies, faster recovery, and better control of symptoms.

Barriers to implementing value-based models

One of the major barriers to starting a conversation about alternative payment models is the fear of Anti-Kickback Statute and Stark Law, according to interviewees. Some companies have approached health systems with proposals for sharing risk, only to be told they could not be allowed under these regulations. Our interviewees told us that while some models may be allowable and that recent proposed updates are a step in the right direction, compliance may still be a burden.

A second barrier is the CMS not setting a precedence in its own approach to paying for medical technologies: When some medtech manufacturers approached it to propose new payment arrangements, they were told that there is not much room to innovate since the medical technology payments may be downstream from what the agency pays the hospital. The good news is that the CMS has shown its willingness to explore payment options by recognizing and developing ICD-10 codes for new technologies, and they are particularly interested in technologies that reduce overall cost and are user-friendly. However, there is currently no standardized approach to support coverage with evidence-development models or new technology add-on models on more than a one-off basis in the United States.

Another major barrier to value-based contracting for medical devices is the need for both medtech companies and health systems or health plans to collect, store, and share data with enough specificity to capture value. For instance, the manufacturer should track the utilization of a given device, which is often not captured in today’s data, nor is it standardized for sharing across entities. And hospitals may not be willing to invest in tracking the performance of technologies or to share the data they do have.

A related issue is the lack of valid, accepted, and meaningful measures of quality that are specific to the medical technology’s value proposition. And even if the technology contributes to a measurable outcome, how much of that outcome can be attributed to the device as opposed to other factors at play, such as the surgical team and the quality of postoperative care?

Overall, medical technologies make up just 6 percent of the total spending on health care in the United States, and companies may not consider it worth their while to go through the hassle of setting up value-based contracts for them, especially if the device or technology serves a small patient population or represents a small portion of their product portfolio. However, for technologies where value is easier to demonstrate (e.g., insulin pumps versus injections) and in some therapeutic areas, where a given devices’ share of sales is large, it might be worth pursuing contracting.

Most stakeholders expect value-based arrangements to accelerate with regulatory changes and better data

Most of our interviewees expect acceleration of value-based arrangements for medical technologies. Key factors that are expected to lead to greater adoption include:

- Regulatory change. In the United States, the Anti-Kickback Statute and Stark Law dampen interest, and in Europe, the disconnect between primary care and secondary/tertiary may also make value propositions challenging. Changes to these regulations could increase adoption of value-based arrangements.

- Ability to track products and data to show their impact on outcomes. Interviewees agreed that data is becoming more interoperable and more robust, leading to better evidence and insights. That said, it still can be challenging to track a particular device used in a procedure and to establish which outcomes are meaningful. Today, some products can show long-term improvement in outcomes, but most health systems and hospitals are interested in more immediate returns. Related to this is the fact that the impact on outcomes should be significant—the patient population needs to be big enough and the impact on the savings and clinical outcomes needs to be significant.

- Support and precedent from the CMS and governments (in other countries) for these arrangements. The pressure on health systems to take risk helps; pilots with medtech companies themselves might be even more influential. More successful examples and pilots can be helpful both in the United States and other countries, but in the United States, the CMS's actions are the most influential.

- Capabilities to put these arrangements in place. Today these are lacking at health systems, health plans, or manufacturers.

In Europe, a Deloitte study based on interviews and a survey conducted in five countries found that “Procurement in the health care sector is clearly moving away from traditional lowest price procurement strategies and product buying. Instead, it is moving its focus toward quality, services, and solutions. True value-based procurement, however, remains in its initial stages of practical implementation.”11

Global government efforts to promote value for medical technologies

National Innovation Funding, France12

In 2007, French authorities introduced Forfait Innovation, the coverage with evidence development (CED) mechanism. The goal was to provide temporary funding of promising and innovative medical technologies to accelerate their introduction. In 2015, the authorities made changes to the law and brought a defined application process with a clear description of which technologies could be candidates for the program. In the revised rule, selection criteria focus on the use of clinical data to demonstrate potential risks. It also demands clinical or economic benefit, which could be a significant benefit for unmet need or decrease in health care expenditure. The clarity and approach of the recent redesign of the Forfait Innovation has generated significant optimism on how France will look into promising medical technologies.

New Methods for Treatment and Screening (NUB), Germany13

Although an exception and only temporary, the law has been in place since 2012, with the aim of remunerating cost-intensive, innovative services and technologies that are used in addition to the procedures included in the valid DRG case-based flat rate. This process is for technologies/procedures considered new. Selection criteria require the procedure to demonstrate value by improving current treatment. Some of the procedures passed include: radio frequency denervation for chronic low back pain and intra-arterial thrombolysis for acute stroke.

Where are the opportunities and where to begin?

Industry stakeholders say that the greatest opportunities for new payment models are in products—including those wrapped with solutions—that:

- Show clear impact within a relatively short period; for example, within three months of a surgery or within a year

- Generate enough spending to be “worth the effort” of setting up payment systems, monitoring outcomes, and making sure that the arrangements meet regulatory tests

- Are in therapeutic areas that are “low-hanging fruit”—that is, in areas where outcomes are being measured, where there is a major population health initiative, or in CMS pilots

One strategy may be to partner with a provider group or disease management organization. The technology manufacturer and the partner together may be able to show impact on outcomes. A technology alone might not make sense for a novel payment arrangement—for example, its specific impact might be too hard to isolate—but if paired with services, it might be able to take risk.

Health plan representatives said they may be interested in opportunities to share in new technology equity opportunities. Many health plans have innovation arms and having skin in the game is attractive provided the product’s value can be adequately demonstrated. One health plan representative told us that he thought offering the investment opportunity to a popular product would interest plans.

Interviewees agreed that CMS payment models are highly influential in creating opportunities. Two new CMS models feature medical technologies, although provider organizations directly take on the risk (see sidebar, “New CMS models featuring medical technologies”).

New CMS models featuring medical technologies

End-stage renal disease (ESRD) treatment choices14

Medicare proposed this demonstration program in July 2019 (comment period ended). It is designed to reward greater utilization of home dialysis and kidney transplantation by rewarding higher use of these options through payments to dialysis facilities and physicians who receive the monthly capitation rate for dialysis care.

How does payment work? There are two parts to the payment incentives. One part—which will have greater weight initially—will be an add-on to the home dialysis rate for participating facilities and physicians. The other part will increase or decrease participating facilities’ and physicians’ overall payment rates to reflect their higher or lower-than-target use of home dialysis.

Who participates? The demonstration proposes to occur within certain geographic areas, where a target of one half of all facilities and physicians would be required to participate.

What’s the medtech angle? Companies that manufacture home dialysis equipment would benefit from higher use of the equipment. No explicit risk-sharing is mentioned, but presumably, equipment manufacturers with better rates of satisfaction and use will help facilities and physicians increase their payment rates.

Radiation Oncology Model15

Medicare proposed this demonstration program in July 2019 (comment period ended). It is designed to address the difference in payment rates between outpatient hospital, physician group practices, and free-standing radiology settings, encourage physicians and providers to consider tradeoffs between number and intensity of treatments, reward higher quality, and reduce spending for Medicare.

How does payment work? The program will set standard payments to providers (outpatient hospitals, physician group practices, and free-standing radiology centers) for 90-day episodes rather than on a per-treatment basis. These payments will apply to Medicare patients with 17 types of cancer (making up 84 percent of radiation therapy episodes today). A discount will be reserved from payment rates, in part to reward performance on quality measures and to save money for the Medicare program.

Who participates? The demonstration proposes to occur within certain geographic areas, where participation would be required.

What’s the medtech angle? Companies that manufacture radiology equipment that can provide equivalent or better therapeutic benefits with fewer treatments within the 90-day episode will help providers do well under this payment model. Those that help providers earn money back based on better quality and consumer satisfaction results will also be more readily used.

Building a value-based contracting strategy

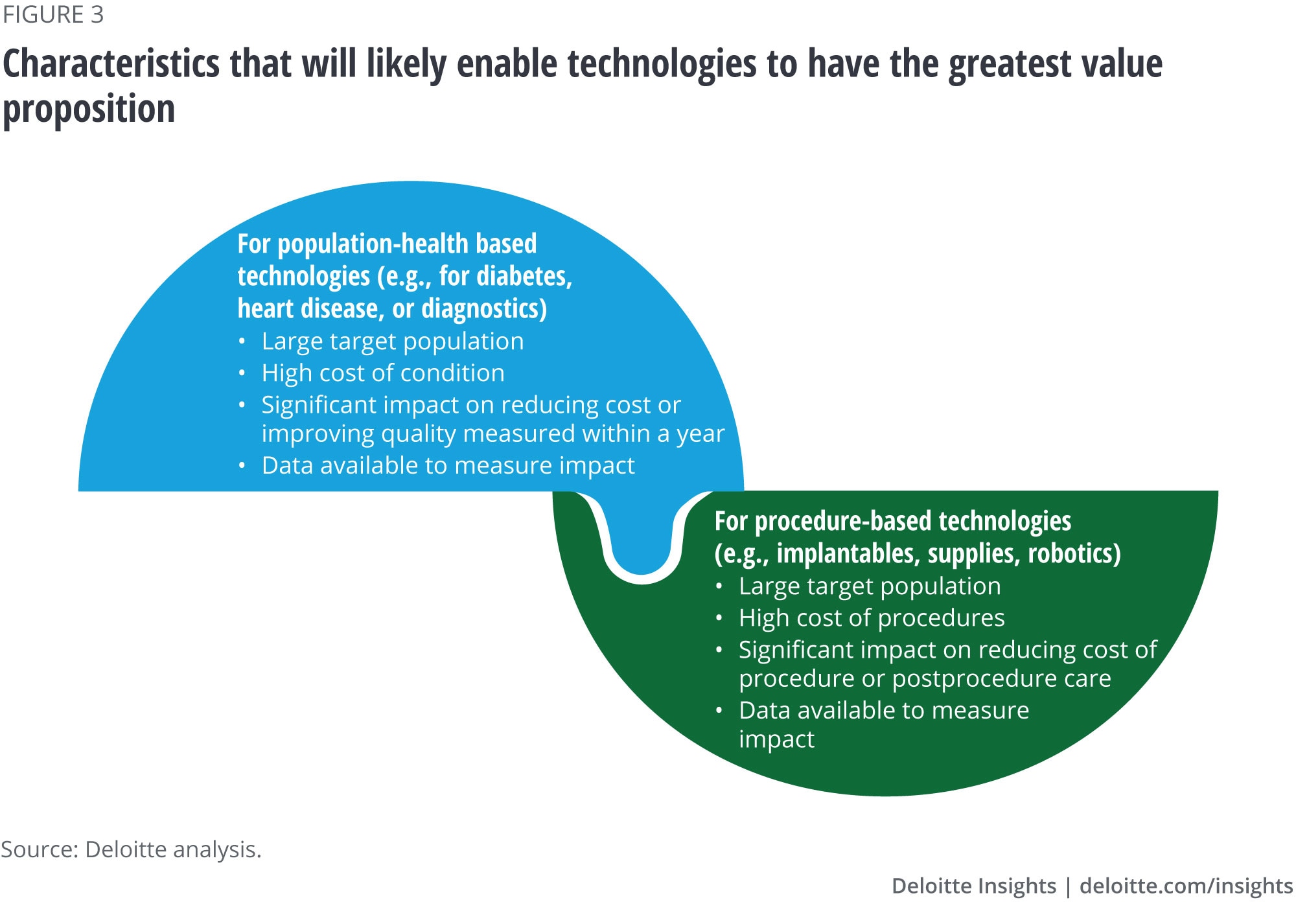

Our interviewees gave us valuable insights on what they think it will take for value-based payment arrangements to be adopted, as well as the benefit to manufacturers—getting paid for a differentiated product that demonstrates clinical and economic value as well as humanistic (patient centric) value drivers such as quality of life and improved mental health status. Our interviewees made it clear that not all products are good candidates for new payment models (figure 3), and not all companies or potential partners are ready to embrace value-based payment models. But those that want market access, market share, or a higher price and offer a product that has a robust value proposition should consider a strategy to build needed capabilities.

Considerations in building a strategy include:

Who to partner with? A manufacturer interested in experimenting with new payment models should start by approaching health systems that have signaled commitment to value-based care by taking on risk or those that are heavily investing in particular therapeutic areas. Manufacturers may wish to partner with technology companies to develop capabilities, including the ability to use data and improve interactions with patients, as we discuss later in this paper.

A government or health plan might be a good target if the technology is paid for separately, makes up a large part of the cost/impact of a therapy area, or shows convincing evidence of saving costs/improving outcomes that go beyond a relatively short time frame (e.g., more than 90 days but probably less than a year or two).

What combinations of solutions to offer? There is no one right answer to this. The combination should demonstrate value and relevance to the therapeutic area and type of procedures. So, if the technology itself far outperforms its competitors in concrete ways that lower the cost of a procedure, no other services might be needed. But if by adding services the manufacturer can show impact, they should consider them. Potential add-on services might include remote monitoring/continuous and actionable data, clinical support people, companion consumer technologies that promote adherence, diet/exercise, etc.

What financial terms to offer? Managing financial risk may not be medtech manufacturers’ competency; so, developing a proposal that creates financial and possible regulatory risk may be intimidating. Partnerships, for example, with specific clinical teams such as hospital departments or medical affairs demonstrating best outcomes, might help deliver better value and outcomes within those agreements. The value of the data itself to both parties—medtech manufacturer and provider or plan—should also not be underestimated.

The agreements themselves will likely hinge on metrics and mechanisms to show that the product or solution achieves these metrics. Consider both: what evidence is needed to show that the solutions achieved the desired market results and in what time frame. Proving that the metrics were met will involve figuring out a data source, who owns that data, how to collect data from it, whether it is automated or not, and whether the information is specific enough to the particular product. Sometimes hospitals will be asked to develop a new system for tracking, which may be costly in terms of information technology investments and staff time.

The best value proposition can tie metrics to a time period and a target that aligns with the health system’s incentives. A hospital that is primarily paid on volume will be less interested in a product that reduces volume of services. Impacts that go beyond one year will be of less interest than more immediate impacts that relate to a bundle or chronic condition over the period during which the health system itself is at risk. A device that has a 10-year battery life compared with one that has a 5-year battery life will have a harder case to make, since many purchasers in the United States don’t cover an individual 10 years later.

The terms also should be consistent with what is permissible from a regulatory perspective: complying with Anti-Kickback Statute and Stark Law and protecting data under HIPAA.

Whom to approach? Many medtech manufacturers of physician-sensitive products tend to approach clinical leaders of hospital departments. For value-based arrangements, consider other potential decision-makers.

Interviewees told us that for hospitals, companies should start with the medical director or department head, who gets the chief medical officer (CMO), and eventually, the CFO to sign off on the cost arrangements. Once the CFO’s approval is secured, the pilot may begin. One interviewee suggested that rather than approach an entire system, a company may approach an individual and find a clinical advocate (CMO/medical director). Another said that for health systems with a dual model (both supply chain– and therapeutic area–focused purchasing), the company might approach both medical and operations leads.

In approaching a health plan, technology companies will likely want to start with the medical director, then the CMO, and finally the contracting head. The CEO is also likely to sign off on these arrangements.

Technology is the enabler. Data is critical to monitor outcomes. The medical technology can itself generate the data needed for tracking patient outcomes. Consider building the right technology into the arrangement and the product.

Trust between parties is critical. Consider a third-party intermediary to analyze the data and decide if a product is meeting the contract’s terms.

Conclusion

Despite challenges, medtech companies expressed a strong interest in and an understanding of the potential benefit from value-based contracts. Industry experts we interviewed for this study agreed that data systems, regulatory considerations, and other changes are aligning to create new opportunities.

Some companies are moving quickly to develop the strategic capabilities needed for these arrangements, including value propositions and go-to-market approaches, positioning themselves to seize new opportunities. Fast followers will likely want to start mapping out their strategies so as not to become price takers and treated as commodities by purchasers rather than differentiated, valuable technologies.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.

Explore more on life sciences

-

Showing cybersecurity's value to health care leadership Article5 years ago

-

Radical interoperability Video5 years ago

-

Intelligent drug discovery Article5 years ago

-

What will health look like in 2040? Video5 years ago

-

Intelligent biopharma Article5 years ago

-

Tackling digital transformation in life sciences Article5 years ago