Ransoming government What state and local governments can do to break free from ransomware attacks

18 minute read

11 March 2020

As malware attacks increasingly hold various governments ransom over critical data, to pay or not to pay can become an impossible dilemma. Taking simple steps to secure IT infrastructure and data can help government organizations avoid this dilemma.

The increasing sophistication of ransomware

In December 1989, computer researcher Jim Bates popped a floppy disk into the disk drive and was shocked at what he saw. On a disk labeled “AIDS Information Version 2.0,” he found, hidden among files containing information on AIDS and the HIV virus, a virus of another kind: a program designed to encrypt the root directory of a computer.1 A few months before, this same disk had made its rounds at a world conference on AIDS. Any researchers unfortunate enough to insert the disk were greeted by large red screen demanding that US$189 be mailed to a post office box in Panama if they wished to use their computer again. This was the world’s first ransomware.

Learn more

Explore the Government & public services collection

Learn about Deloitte’s services

Go straight to smart. Get the Deloitte Insights app.

While distribution and payment methods may have advanced beyond floppy disks and post office boxes, the basics of ransomware largely remain the same: Hackers gain access to a system and, once in, use malware to lock data behind complex encryption; in order to regain access to that data, victims must pay a ransom ranging from a few hundred dollars to several millions. As connected devices and digital systems proliferate at breakneck speed, government services ranging from health care to policing to public education are increasingly managed through digital networks and software.

Governments then may find themselves vulnerable as they try to keep pace with cybersecurity developments, often on increasingly old systems. Vulnerable networks, critical citizen services, and paying ransoms can create a positive feedback loop where successful ransomware attacks can encourage more and more attacks asking for more money. In such situations, governments often face a dilemma: paying ransoms that can likely fuel more attacks and other illicit activities, or dealing with the considerable cost of losing data necessary to provide public goods and services.

Unfortunately, there is no silver bullet for ransomware. It takes hard work, starting with first understanding what makes governments attractive targets for ransomware and then putting in place new tools, new policies, and a new approach to cybersecurity. A few governments are already protecting themselves against and recovering from ransomware attacks, setting an example for other governments. Ultimately, reversing the current trend in ransomware attacks rests on doing the basics well: building and operating networks well, and responding well to inevitable attacks.

Why governments seem particularly vulnerable

Along with the health care industry, governments are among the top targets for ransomware. Ransomware is a particularly powerful weapon against governments, who must provide public services and cannot afford, financially or civically, to have data compromised to the point of governance paralysis. The cost of a police department unable to serve and protect the community or a school district unable to educate the community’s children escalates quickly. As a result, government often see paying the ransoms as the only logical solution. After all, not paying the ransom and having to recoup lost data and systems can often be significantly more expensive than the ransom.

Beyond being a desirable target, governments can also be a vulnerable one, for several reasons:

Growing attack surface

A successful ransomware attack typically needs three ingredients: a vulnerability, or “exploit,” in the network or system to create access, encryption to block access to the data and create the need to pay ransom, and a payment method to collect that ransom.2 With powerful algorithms and bitcoin offering easy off-the-shelf methods for encryption and payment, exploits are often the driver behind new waves of ransomware attacks.

Governments are now providing more services to citizens through digital means than ever before. Indeed, the total number of computers used by government organizations have grown significantly. A few decades ago, there may have been a few computers in the central office of local school districts or police departments, but today every squad car has a computer, and each classroom likely has a few. Each of these computers is a potential access point for malicious malware, with the result that the potential attack surface that a government agency must protect has grown significantly without commensurate investments in cybersecurity.3

This trend is not likely to stop either. Connected traffic cameras, ambulances, trash trucks, parking meters, and libraries (just to name a few) make up an incredibly varied, constantly growing array of endpoints, all connected to state and local government networks—and all potentially vulnerable to attack, creating a larger attack surface.4

Outdated technology and inadequate defenses

While new technology coming online can pose a challenge for governments, the lack of new technology can too. Many governments struggle to keep pace with the rapid pace of technology refresh cycles.5 Tight budgets limit the amount of modernization that can take place, and even if budget is available, the tech refresh process itself can strain government IT departments. Private sector networks are often designed with enough redundancy to support taking portions offline for tech refresh without suffering a loss in capability, but state and local government network operations teams rarely have that luxury. Taking a system offline to replace or upgrade it generally means some service is unavailable to citizens, making modernization a tough tradeoff for government leaders.6

Even current-standard, updated networks require constant effort to maintain security patches and configurations, a task that even the most well-staffed, well-trained cybersecurity staff could find difficult. For state and local governments operating with older, legacy systems, keeping those systems up to date can be a daunting battle. An audit conducted in Atlanta, not long before the 2018 ransomware attack, found up to 2,000 network vulnerabilities.7 However, as the staggering costs of recovery—US$17 million in the Atlanta attack—become more widely known, government leaders may begin to see the necessity of timely maintenance and modernization.8

As important as continuous maintenance of machines is the basic cybersecurity education and training for every civil servant, employee, contractor, or elected official who has access to government networks. It can take only one click to compromise a network, and everyone who is part of the network should understand the basics of how to protect it. But regular cybersecurity training costs time and money, and for local governments on tight budgets and with too few staff, this could seem like a near-impossible ask. The most advanced cybersecurity tools in the world cannot make up for poorly trained workers.

The cost of being small

However, the most significant challenge is not typically technology—it is people. New systems do not come online and legacy systems do not get patched without trained staff to do the work. Attracting and keeping the right number of trained technology staff, and cybersecurity staff specifically, is perhaps the greatest challenge for many governments.

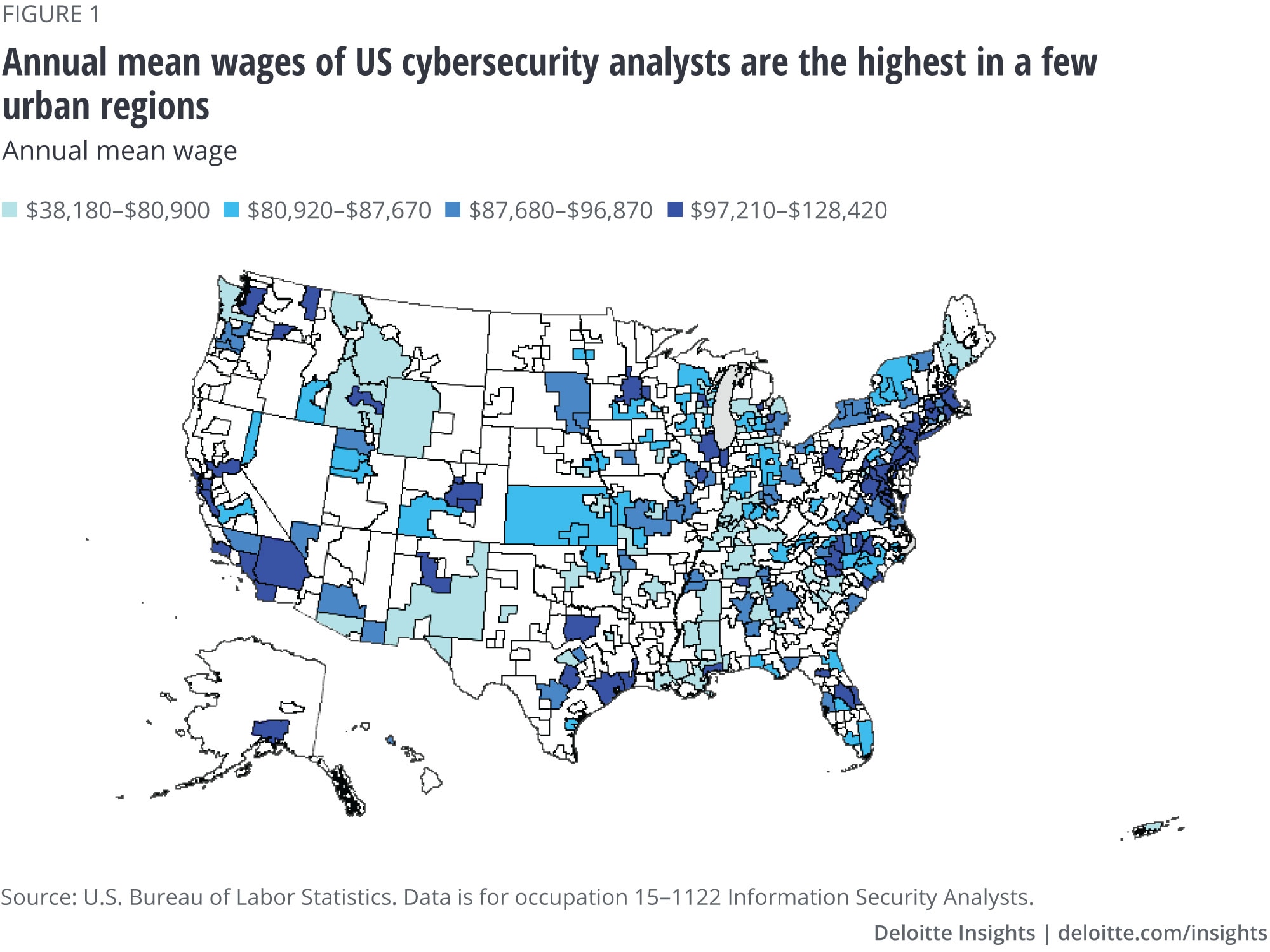

Cybersecurity talent is in high demand today in every sector. According to the 2017 global information security workforce study, two-thirds of its nearly 20,000 respondents indicated that their organizations lack the number of cybersecurity professionals needed for today’s threat climate.9 By 2021, 3.5 million cybersecurity jobs are expected to remain unfilled.10 With every organization looking for cyber talent from a limited pool, the bidding war for that talent can become intense. The US Department of Labor reports that the median salary for cybersecurity talent is nearly US$100,000.11

Faced with small IT budgets, state and local governments can struggle to attract and retain the cybersecurity talent they need. A biannual NASCIO/Deloitte cybersecurity survey found that a lack of budget has been the #1 concern of state-level chief information security officers (CISOs) every year since 2010. The majority of states spend only 1 to 2 percent of their IT budgets on cybersecurity, and nearly half of states do not have a cybersecurity budget that is separate from their IT budget.12 In contrast, federal-level agencies and private sector organizations generally spend between 5 and 20 percent of their IT budgets on cybersecurity.13

Skilled cybersecurity talent in the United States is attracted to high-wage, high-demand jobs in a few select urban areas (figure 1). The result is that most state-level IT security organizations are staffed at drastically lower levels (6–15 cyber professionals in an organization) than a comparable-sized financial organization in the private sector (more than 100).14 The problem is compounded when you consider that on average less than 15 percent of IT staff work on cybersecurity.15 So many local governments are left with, at best, one cybersecurity professional, though often that individual has to split time between cybersecurity and other IT tasks. A part-time cybersecurity effort fighting against full-time, professional attackers is never going to be a fair fight.

To pay or not to pay?

As an attractive target, more and more governments are finding themselves in the crosshairs of ransomware attacks. While the US federal government doesn’t encourage payment of ransom, the decision government agencies face isn’t an easy one: either pay the ransom to (maybe) regain access to your systems and data while likely fueling additional criminal activities with money from the ransom, or don’t pay the ransom and absorb the almost-always greater costs of system restoration and lost revenue.

The costs associated with restoring the system and loss of revenue when systems are down often significantly outweigh the ransom demand. For example, in May 2019, the city of Baltimore was hit with a ransomware attack demanding US$76,000, and it decided not to pay. This decision cost the city at least US$18.2 million in a combination of restoration costs and lost revenues.16 Hackers purposely keep the ransom demands lower than what it would cost to recover the systems, making paying the ransom seem to be a better economic choice for underfunded local governments.17

Other municipalities have seen those costs and chosen another route. In June 2019, Lake City, Florida, reportedly agreed to pay ransom to hackers to regain access to its municipal computer systems two weeks after systems were disrupted. According to news reports, Lake City agreed to pay the US$460,000 ransom. Lake City also had cyber insurance that covered the payment itself, leaving the city with only a US$10,000 deductible to pay.18 But even the decision to pay is not a guaranteed path to recovery. Some malware such as NotPetya may ask for ransom even though it cannot ever decrypt the data, while some attackers may simply refuse to send a key.19 According to one survey of 1,200 cybersecurity professionals, less than half of those who paid ransom regained access to their data.20

But why the big increase in ransom attacks now?

All of this seems to beg the question, why does there seem to be a recent explosion of ransomware targeting state and local governments? After all, governments have had limited IT budgets and aging legacy systems for decades, and ransomware itself is not new, so what has changed?

Impact of cyber insurance

Certainly, the recent increase in cyber insurance plays some role. That growth has been driven by two factors. First, for many organizations, transferring cybersecurity risk to an insurer can be a cost-effective strategy in a rocky cyber world. Second, the market is proving an attractive one for insurers. While many other areas of insurance are flat, cyber insurance remains a profitable, if uncertain, segment. The loss ratio for US cyber policies was about 35 percent in 2018 compared with 62 percent across all property and casualty insurance.21 In other words, for every dollar in premiums collected from policyholders, insurers paid out roughly 35 cents in claims, making cyber insurance nearly twice as profitable as other types of insurance. However, this profitability may be largely due to the uncertainty related to the cyber insurance no-win situation in which insurers find themselves: When attacked, no organization wants to be helpless, but those that use cyber insurance policies to cover ransom payments may unintentionally be fueling the increase in ransomware attacks.

Government-specific circumstances

More cyber insurance policies paying out more ransoms may be part of the issue, but it cannot be the whole story. After all, the majority of cyber insurance policies are issued to commercial organizations, not to governments. So why are governments such a target right now? The answer may lie in the peculiarities of some of those policies issued to governments.

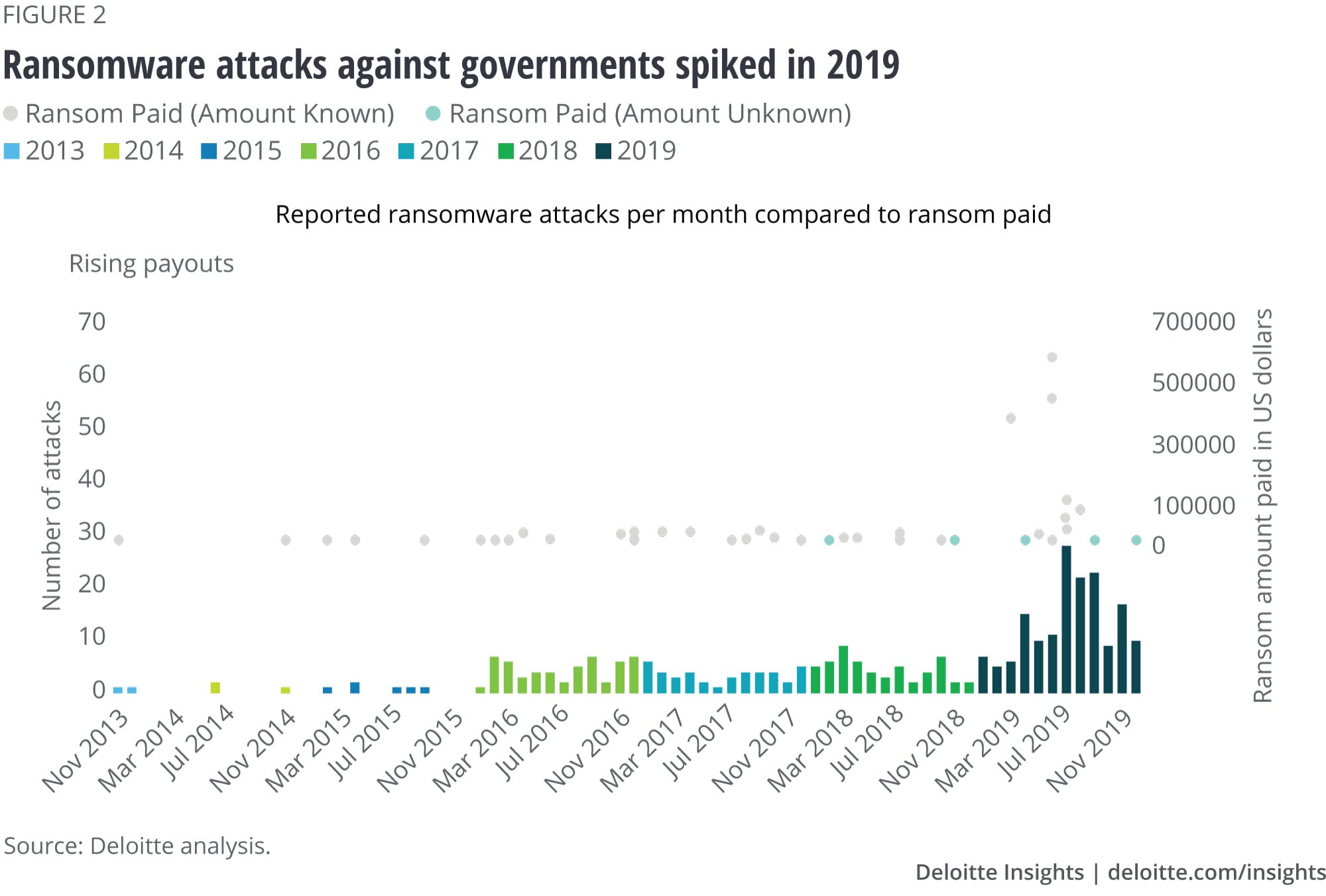

The simple answer is that cyber insurance, poor defense, and criticality of government services are creating a positive feedback loop where attackers are asking for and getting more money more often. For example, in the second quarter of 2019, governments that chose to pay ransoms ended up paying 10 times more than their commercial counterparts.22 This appears to create a situation where, aided by cyber insurance, more vulnerable government organizations are paying more than better-protected ones. Like blood in the water, this appears to have attracted at least one organized cybercrime syndicate in Russia, which created the Ryuk ransomware strain that appears to be behind many recent attacks.23 While diverse in its targets, this syndicate appears to be specifically targeting US state and local governments and demanding nearly 10 times higher ransom than average attacks.24

Like the chicken and the egg, it is difficult to know whether increased ransom demands are driving higher payments or higher payments are attracting larger demands, but the link between them seems clear. To help illustrate this relationship, we drew on a number of data sources to compile a database of ransomware attacks targeting public sector organizations beginning in 2013. Along with a significant increase in attacks recently, there also appears to be a clear correlation between the ransom paid and volume of attacks (figure 2).

Therefore, while paying the ransom in a ransomware attack may seem to be an easy, short-term solution, in the long run, it may make the problem worse, encouraging attackers to continue to target governments. Incentives should be put into place to make sure that governments don’t see paying the ransom as the better, or only, option.25

Finding a third way

Clearly, both typical methods of response to ransomware are not sustainable. Not paying ransom can lead to massive costs and the loss of critical data and citizen services. Paying ransom may save money in the short term but may also invite more attacks in the long term. To move forward, governments should consider an approach to dealing with ransomware, built on doing three things well: building well, operating well, and responding well.

Building well: Making governments hard targets

The first step should be to avoid becoming a target in the first place—partly by developing smarter systems, and partly by having skilled staff to work with these systems.

Develop a smart systems architecture

No system can ever be completely secure. Unknown security flaws that could provide access into a system will likely always exist. However, how an organization manages its data can mitigate the consequences of any ransomware attack.26 Developing a system architecture where the most critical data is compartmentalized can make it more difficult for hackers to encrypt enough critical information to create leverage and demand a ransom. This compartmentalization is as much about function as physical connectivity. Disabling extraneous services on connected devices and putting in place policies that prohibit checking email or playing games on critical hardware can be important defensive measures.27

Developing system backups should be the next, and possibly most important, step.28 Air-gapped backups—isolated computers or systems that don’t have connections to external links—or even tape backups can help keep critical business information insulated from ransomware attacks. The air gap decreases the likelihood that ransomware can infiltrate the backup, and in the event it does enter, the design of the vault prevents the ransomware from executing its payload (figure 3).29 Similarly, tape back-ups can help restore data without the risk of reintroducing ransomware. Regardless of method, data backups inaccessible by ransomware attacks are another way organizations can avoid falling prey to criminals who hope to hold their information hostage.

Build a cyber-aware workforce

The best technology and business processes in the world are useless without the skilled staff to implement them. Cybersecurity talent is in high demand, so governments must be creative about ways to attract and retain that talent, including sharing talent via rotational assignments within government, improving pay and benefits packages, or looking to the gig economy.30 For example, Michigan’s Cyber Civilian Corps not only offers new ways to attract talent, its CISO-as-a-service offering also helps to make that talent available to smaller governments that otherwise could not afford it.31

But training and reskilling efforts cannot end with IT staff; every worker should be cyber-aware. Programs such as the Federal Cybersecurity Reskilling Academy that educates non-IT workers in cybersecurity basics can be valuable tools in creating an aware and active workforce.32

Operate well: Minimizing risk

Some ways in which risk can be minimized include improving basic cyber hygiene and using war-gaming to prepare for real-life attacks. State and local government leaders and their teams should know how to respond if attacked just as emergency responders know how to respond during a fire, car accident, or severe weather.

Improve basic cyber hygiene

The maintenance of legacy systems can be a critical vulnerability for many governments, making improved cyber hygiene important to reducing the overall risk of attack. Timely application of software patches and updates are imperative, as are regular system backups to an air-gapped recovery vault. Updates can help limit the vulnerability of a government’s systems, while the system backups could speed recovery time if the systems are attacked and avoid the need to either pay ransom or spend more in recovering the data. Improving basic cyber hygiene also means regular trainings and evaluations for all staff. While the cost of effective training programs may seem like a less-than-critical expense, it’s generally far less than the cost of a ransomware attack. It is also feasible that as rates of ransomware attacks increase, insurers may require policyholders to meet certain basic requirements, including staff trainings, in order to pay out on policies.

War-Gaming

Planning for a ransomware attack begins with a system audit to identify which systems, information, and people are critical to the organization’s operations and most vulnerable to ransomware. For example, a police department would cease to function if its emergency dispatch system was compromised, but it could function if the system tracking employee time sheets was compromised. With that information, governments can then test their protective measures and responses using war-gaming and simulation.

Cyber war-gaming and simulation are valuable tools in preparing staff and ironing out kinks in processes. Rehearse with a realistic scenario so that you’re able to simulate the decisions that you might have to make. You don’t want to be forced to decide under duress. Often, only during such simulations do leaders begin to see the many details that they must master—from the logistics of transferring bitcoin to learning what exactly is covered by a cyber insurance policy. Government can use the successes and failures of the war-game to craft a playbook spelling out responsibilities and key tasks in the event of an attack to speed response. Speedy recovery depends on everyone knowing the plan and being able to execute it quickly, and for that, there is no substitute for practice.

Responding well: Getting back to normal quickly

Attacks can strike even the best-prepared government, so knowing how to respond and restore critical services to citizens as quickly as possible is essential.

Deploy emerging technologies

Finding and retaining skilled cybersecurity talent will likely remain a challenge in the near future, so deploying emerging technologies that can make the existing workforce more effective can be a significant cost advantage to governments. For example, artificial intelligence (AI) can help prevent ransomware attacks by blocking unusual downloads from links that employees unwittingly click on.33 The city of Las Vegas has used AI to detect and respond to cyber threats for three years with great success. In the words of director of innovation and technology, Michael Sherwood, “Ransomware can spread across your network rapidly, so you need tools that can prevent that from occurring. AI can autonomously take control and provide split-second reactions, which is very useful for preventing damage.”34

Adopt an ecosystem approach to cyber

Governments should not try to go it alone. Information-sharing bodies such as industry-specific organizations can link governments to other local governments and organizations so that they can learn from each other’s successes and failures.35 Similarly, staying in touch with external researchers, vendors, and law enforcement can help governments access new tools and technologies and create the relationships that will likely be needed if a crisis should ever occur.

Finally, sharing information about ransomware experiences, even when it is uncomfortable or potentially embarrassing, can be key to the “herd immunity” that can keep other governments safe. Although there is currently no legal requirement in the United States to report ransomware attacks, those reports are important to understand the technical nature of attacks to both find perpetrators and help others protect themselves. While some governments are beginning to consider reporting requirements—Texas, for example, is considering a law requiring ransomware reporting— government leaders at all levels should consider devising and practicing some form of voluntary reporting procedure.36 It will be important for local governments to coordinate outside of their typical state silos through the establishment of cyber monitoring and incident response services provided across jurisdictions.

Success is possible

These steps toward a new approach to ransomware resilience represent a significant amount of work. Government entities need to become resilient in a world where a constant threat of a cyberattack is the “new normal.” But the good news is that success is possible.

Take Lubbock County, Texas, for instance. The IT department gets calls about strange behavior on Lubbock County's 1,300 computers all the time. But one call about icons changing on a worker’s desktop in real time caught the department’s attention. It was a clear sign of an attack. By quickly isolating the affected computers, the Lubbock County IT staff was able to stop the ransomware attack before it locked down any critical systems. Lubbock County was one of 23 local governments hit by ransomware in August 2019 in Texas alone, yet it appears to be the only one that successfully stopped the hackers.37 Though hardly revolutionary, its actions show how training and resources—and a bit of luck—can thwart hackers who have been hobbling US cities and counties.

Ransomware is a hard problem for governments. It springs from a variety of sources and demands an entirely new approach if governments are to free themselves from the difficult dilemma of paying versus not paying ransom. The good news is that a clear vision and a few concrete actions can help secure government systems and the valuable services they provide to all citizens.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.

More from the Government & public services collection

-

The realist’s guide to quantum technology and national security Article5 years ago

-

Cyber everywhere: Building cybersecurity, one vehicle at a time Article5 years ago

-

Government’s cyber challenge: Protecting sensitive data for the public good Article8 years ago

-

The revenue agency of the future Article5 years ago

-

Crafting an AI strategy for government leaders Article5 years ago

-

Government executives on AI Article5 years ago