Crafting an AI strategy for government leaders Does your agency have a holistic AI strategy?

27 minute read

04 December 2019

William D. Eggers United States

William D. Eggers United States Tina Mendelson United States

Tina Mendelson United States Bruce Chew United States

Bruce Chew United States Pankaj Kishnani India

Pankaj Kishnani India

Artificial intelligence in all its forms can enable powerful public sector innovations in areas as diverse as national security, food safety, and health care—but agencies should have a holistic AI strategy in place.

A strategy is crucial for AI success

The city of Chicago is using algorithms to try to prevent crimes before they happen. In Pittsburgh, traffic lights that use artificial intelligence (AI) have helped cut traffic times by 25 percent and idling times by 40 percent.1 Meanwhile, the European Union’s real-time early detection and alert system (RED) employs AI to counter terrorism, using natural language processing (NLP) to monitor and analyze social media conversations.2

Learn more

Explore the Government & public services collection

Download the Deloitte Insights and Dow Jones app

Subscribe to receive related content from Deloitte Insights

Such examples illustrate how AI can improve government services. As it continues to be enhanced and deployed, AI can truly transform this arena, generating new insights and predictions, increasing speed and productivity, and creating entirely new approaches to citizen interactions. AI in all its forms can generate powerful new abilities in areas as diverse as national security, food safety, regulation, and health care.

But to fully realize these benefits, leaders must look at AI strategically and holistically. Many government organizations have only begun planning how to incorporate AI into their missions and technology. The decisions they make in the next three years could determine their success or failure well into the next decade, as AI technologies continue to evolve.

It will be a challenging period. But such transformations, affecting as they do all or most of the organization and its interactions, are never easy. The silver lining is that agencies have spent the last decade building their cloud, big data, and interoperability abilities, and that effort will help support this next wave of AI technology. AI-led transformation promises to open completely new horizons in process and performance, fundamentally changing how government delivers value to its citizens.

But this can’t be achieved simply by grafting AI onto existing organizations and processes. Maximizing its value will require an integrated series of decisions and actions. These decisions will involve complex choices: Which applications to prioritize? Which technologies to use? How to articulate AI’s value to the workforce? How can we manage AI projects? Should we use internal talent, external partners, or both?

This study outlines an integrated approach to an AI strategy that can help government decision-makers answer these questions, and begin the effort required to best meet their own needs.

Overlooking an AI strategy is risky

Without an overarching strategy, complex technology initiatives often drift; at best, they fix easy problems in siloed departments and at worst, they automate inefficiencies. To achieve real transformation across the organization and unlock new value, effective AI implementation requires a carefully considered strategy with an enterprisewide perspective.

But AI strategy is still pretty new—and for many organizations, nonexistent. According to a recent IDC survey, half of responding businesses believed artificial intelligence was a priority, but just 25 percent had a broad AI strategy in place. A quarter reported that up to half of their AI projects failed to meet their targets.3

And government is behind the private sector on the strategy curve. In a 2019 survey of more than 600 US federal AI decision-makers, 60 percent believed their leadership wasn’t aligned with the needs of their AI team. The most commonly cited roadblocks were limited resources and a lack of clear policies or direction from leaders.4

But a coherent AI strategy can attack these barriers while building a compelling case for funding. A winning plan establishes clear direction and policies that keep AI teams focused on outcomes that create significant impacts on the agency mission. Of course, strategy alone won’t realize all the benefits of AI; that will require adequate investments, a level of readiness, managerial commitment, and a lot of planning and hard work. But an effective AI strategy creates a foundation that promotes success.

What constitutes an effective AI strategy for government?

For some, an AI “strategy” is simply a statement of aspirations—but since the lack of planning frustrates and confuses implementation efforts, this definition is clearly inadequate. Other strategies treat AI purely as a technical challenge, with a narrow plan based on a handful of incidents. This limited focus risks missing opportunities and the organizational changes needed to produce a truly transformational impact on performance and mission.

An effective strategy should align technological choices with the overarching organizational vision and, drawing on lessons learned from past technology transformations, incorporate both technical and managerial perspectives.5 A holistic strategy, in turn, should support the broader agency strategy as well as federal goals for AI adoption. Because of the rapid evolution of AI, strategies also should be updated periodically to keep up with technological developments.6

What does this mean for government leaders charged with AI strategy? The scholar Michael Porter has observed that “The essence of strategy is choosing what not to do.”7 With so many different types of technology and potential opportunities, leaders with limited resources should decide carefully about the use of AI—and the choices can seem overwhelming.

In their book Playing to Win, A.G. Lafley and Roger Martin introduce a pragmatic framework that we build upon here.8 The strategic choice cascade (figure 1) is adapted here for government AI. It’s based on the premise that strategy isn’t just a declaration of intent, but ultimately should involve a set of choices that articulate where and how AI will be used to create value, and the resources, governance, and controls needed to do so.9

This approach has five core elements—five sets of critical choices—that, as a whole, comprise a clearly articulated strategy. The first choice an organization must make concerns vision, specifically its level of AI ambition and the related goals and aspirations. With that vision as a guide, the next two elements concern choosing where to focus AI attention and investment, in terms of problem areas, mission demands, services and technologies, and how to create value in those areas, including an approach to piloting and scaling. The final two choices in the cascade concern the capabilities and management systems required to realize the specified value in focus areas. They answer questions such as, “What culture and capabilities should be in place?” including personnel, partners, data, and platforms; and “What management systems are required?” including performance measures, change management, governance, and data management.10

An integrated and holistic strategy

These five sets of choices link together and reinforce one other,11 like the DNA’s double helix, with entwined strands including technology as well as managerial and organizational choices. They ensure that the agency’s AI goals are clearly linked to business outcomes and identify the critical activities and interconnections that can help achieve success. Figure 1 illustrates some of the individual choices at each stage through the twin lenses of management and technology.

You need both strands to capture the full value of AI. Without understanding the technology and its potential, decision-makers can’t identify transformative applications; without a managerial perspective, technological staff can fail to identify and address the inevitable change-management challenges. Regardless of their role within the organization, however, government planners must sift through an assortment of potential issues, including changing workforce roles, as well as the data security and ethical concerns that arise when machines make decisions previously made by people.

And these issues are amplified when an AI program’s goal is not just incremental but dramatic improvement.

The five elements of a winning AI strategy

Let’s take a closer look at each element of the strategic choice cascade and see how government agencies are using them in their AI strategies.

Vision: What is our level of AI ambition?

“ Transform the Department of Energy into a world-leading AI enterprise by accelerating development, delivery, and adoption of AI.”—Artificial Intelligence and Technology Office, US Department of Energy12

In 2019, the US Department of Energy (DoE) issued this statement of its AI goals and aspirations to transform its operations in line with national strategy. The US Office of the Director of National Intelligence issued a similar vision statement, declaring that it will use AI technologies to secure and maintain a strategic competitive advantage for the intelligence community.13 Both examples represent a high level of AI ambition, directed toward broad, mission-focused transformation.

Other agencies may have less ambitious goals; they may wish to use AI to address a particular, long-standing problem, to redesign a specific process, to free up staff, increase productivity, or improve customer interactions. But while government AI strategies can have multiple objectives and ambitions, all of them must consider the well-being of people and society. For example, AI-based intelligent automation can help make decisions for both simple and complex actions. But agencies that contemplate delegating more decision-making to machines must be able to understand and measure the resulting risks and social impacts, as well as the benefits. Thus, communicating and socializing the AI strategy with citizens is key to gaining wider acceptance for AI in government.

For this reason and others, the organization’s goals, aspirations, or requirements regarding the ethics of AI should be involved in this and at all levels of the cascade.

Regardless of the ambition, listing aspirations and goals is only a first step. As the vision crystallizes, the next steps—the identification of opportunities and execution requirements—come into focus. As the DoD writes in its AI strategy, “Realizing this vision requires identifying appropriate use cases for AI across the DoD, rapidly piloting solutions, and scaling successes across the enterprise.”

Vision: Strategic choice questions to address

What specific goals, aspirations, and requirements do we have for AI?

Which elements of our larger strategy and goals will AI support?

What’s the long-term ambition behind our investment in AI?

How will our organizational values help us deal with questions of ethics, privacy, and transparency?

Will AI produce savings or some other positive outcome to justify the investment?

Focus: Where should we concentrate our AI investments?

“ The Department of Defense aims to apply AI to key mission areas, including:

- Improving situational awareness and decision-making with tools, such as imagery analysis, that can help commanders meet mission objectives while minimizing risks to deployed forces and civilians.

- Streamlining business processes by reducing the time spent on common, highly manual tasks and reallocating DOD resources to higher-value activities.”

—US Department of Defense AI strategy14

AI-based applications can reduce backlogs, cut costs, stretch resources, free workers from mundane tasks, improve the accuracy of projections, and bring intelligence to scores of processes, systems, and uses.15 A variety of solutions are available; the important question is the choice of problems and opportunities.

Which applications and problems should we tackle?

The DoE focuses its technology-based initiatives in this way:

The mission of the Energy Department is to ensure America’s security and prosperity by addressing its energy, environmental and nuclear challenges through transformative science and technology solutions.16

Its budget priorities reflect this commitment. Much of DoE’s planned US$20 million for research and development in AI and machine learning will go toward two goals: more secure and resilient power grid operation and management, and research toward transformative scientific solutions.17

Specific statements of intent provide “guardrails” for DoE decision-makers, keeping them focused on priority needs. Each choice involved may be explained and championed separately, but, in practice, each choice must align with and reinforce others. In this case, DoE’s “where to focus” choice was reinforced by its “management systems required” decision to launch the Artificial Intelligence and Technology Office in September 2019. The organization will focus on accelerating and coordinating AI delivery and scaling it across the department.18

Back office, customer engagement, mission focus—or all three?

Leaders deciding where to focus their AI efforts can consider the question through several different lenses. One might consider which problems to address; what processes to focus on; or what part of the organization would benefit most from the investment. There’s no one “best way,” and in fact looking through multiple lenses can be helpful.

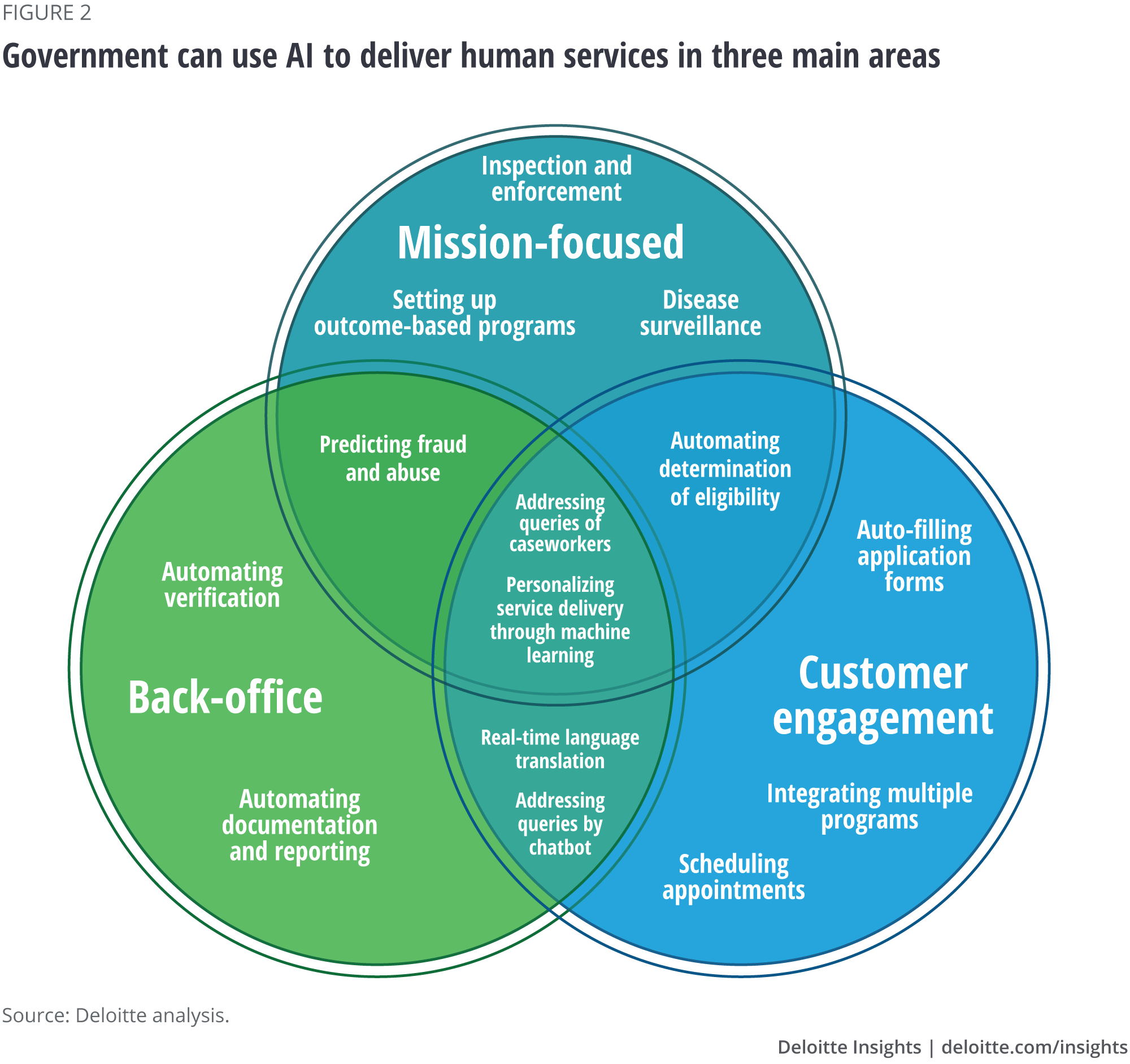

Figure 2 illustrates potential AI applications in human services, with examples from all three lenses. In human services, AI has considerable potential to transform processes for caseworkers and administrators, improve service, and enhance mission outcomes. Policymakers will have to determine how to prioritize advanced technological solutions. Should AI be used to automate case documentation and reporting? To create chatbots to answer queries? To compare our beneficiary programs with those of other organizations, to better identify the optimal mix of services? Or should we strive for all three goals?

A broad initial view can help government agencies find the right blend of uses. It can help them avoid becoming focused on a single class of applications—simple automation of back-office tasks, for example—at the expense of more transformative opportunities.

Every agency faces a similar set of questions about where to focus its activities, and how to balance quick solutions with those promising longer-term transformation. A carefully articulated AI strategy that clearly establishes priority focus areas should answer these questions. To do so, it must consider both managerial and technological perspectives.

The technology perspective

The technological focus should be determined by the mission need. Broadly, the pool of available technologies roughly corresponds with each of the bubbles in figure 2. Intelligent automation tools, also called robotic process automation, are highly relevant to back-office functions. Customer interaction or engagement technologies bring AI directly to the customers, whether they’re citizens, employees, or other stakeholders. Finally, a variety of AI insight tools can identify patterns or develop predictions that can be highly relevant to many agency missions.

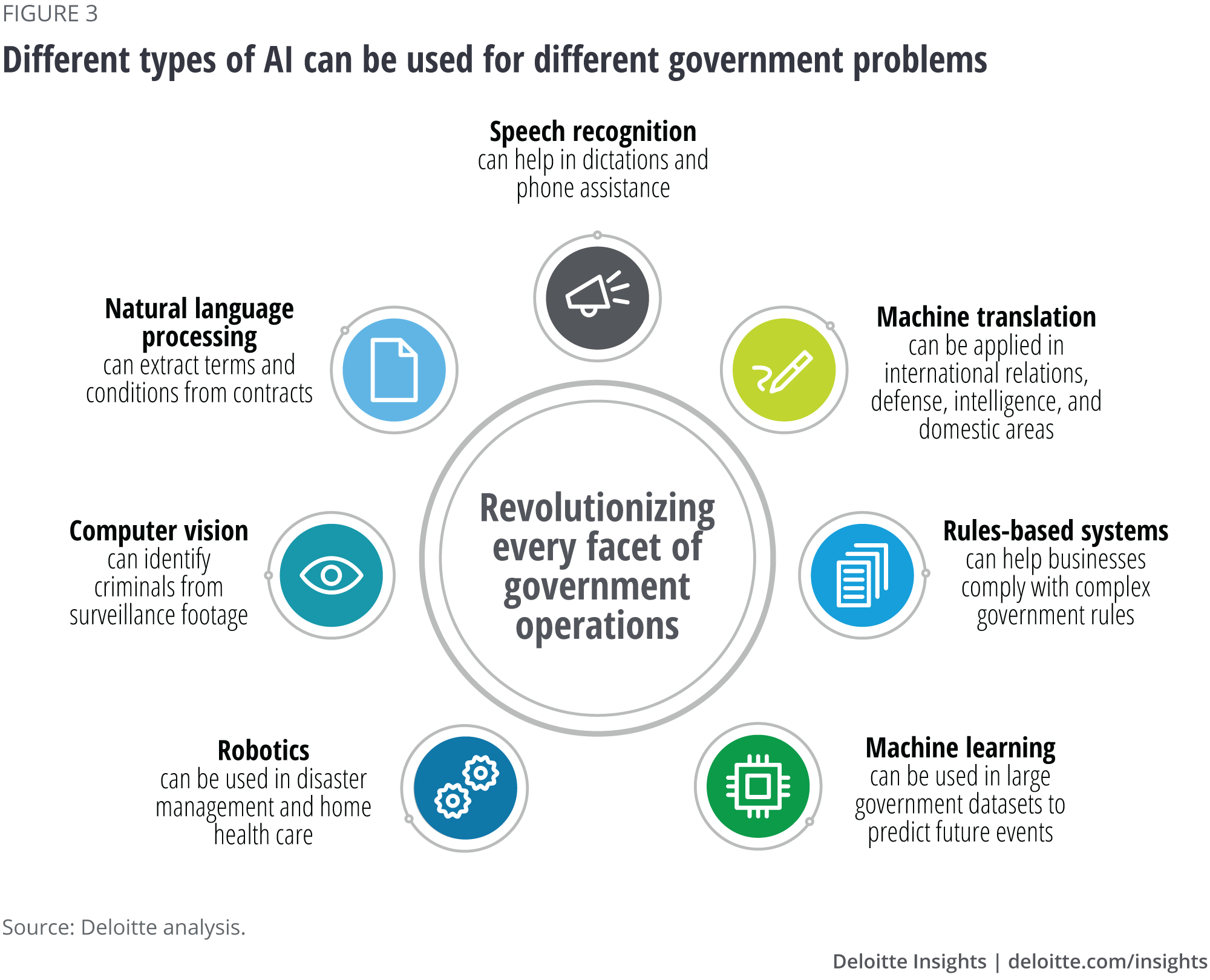

For agencies beginning their AI journey, this level of detail will be sufficient. Others may benefit from a deeper dive into the opportunities created by specific technologies being deployed in a variety of government settings, separately or in concert. These applications include intelligent robotics, computer vision, natural language processing, speech recognition, machine translation, rules-based systems, and machine learning (figure 3).

The technology perspective, obviously, must go beyond separate innovations to consider how they’ll be used. Any of these technologies can be implemented in different ways, with differing degrees of human involvement:

- Assisted intelligence: Harnessing the power of big data, the cloud, and data science to aid decision-making.

- Augmented intelligence: Using machine learning capabilities layered over existing systems to augment human ability.

- Autonomous intelligence: Digitizing and automating processes to deliver intelligence upon which machines, bots, and systems can act.

A skilled AI implementation team will understand that each technology has different uses, with distinct capabilities, benefits, and weaknesses. The list of possible use cases and available technologies will continue to expand and grow in significance. (See AI-augmented government for a primer on AI technologies and their deployment in government.)

The focus questions for the technology strategy have been answered when the organization knows where to concentrate its investments, in terms of problems and processes, with a level of detail that seems appropriate to the decision-makers. As with all strategies, more detail will be needed as the strategy is translated and further developed within the organization.

Focus: Strategic choice questions to address

Managerial

- Who will be the user of AI, and who will benefit from its use?

- Which problems will AI address?

- How will AI transform our mission or the way in which we pursue it?

- In which mission areas or functions will AI be used? And to further which mission?

- Which processes and services will AI affect? Back-office processes, customer interfaces, or other activities?

Technical

- Which goals should we pursue with AI, and which technology or combination of technologies should we use?

- Will the application involve assisted, augmented, or automated intelligence?

- How should we prepare for and accommodate future developments in AI and the underlying technologies? (Note that choices may need to be reexamined as capabilities and resources are explored.)

Success: How will AI deployment create value?

“It is likely that the most transformative AI-enabled capabilities will arise from experiments at the “forward edge,” that is, discovered by the users themselves in contexts far removed from centralized offices and laboratories. Taking advantage of this concept of decentralized development and experimentation will require the department to put in place key building blocks and platforms to scale and democratize access to AI. This includes creating a common foundation of shared data, reusable tools, frameworks and standards, and cloud and edge services..”—US Department of Defense AI strategy19

AI-based technologies can create such wide-ranging impacts in so many fields and at so many levels that it can be difficult to imagine how it would change our own work environments. Next to budget constraints, “lack of conceptual understanding about AI (e.g., its proposed value to mission)” was the second-most common barrier to AI implementation cited by respondents in a 2019 NextGov study.20

That’s why an AI strategy should articulate its value both to the enterprise in general, including the workforce, and to those affected by its mission, which includes taxpayers as well as public and private stakeholders, reflecting a clear alignment with broader goals, strategies, and policies. Proactive communication regarding the value that AI creates for an agency and those it serves should help to allay fears of misuse and enhance trust.

Articulating the value of AI

It may help to focus on a few transformative capabilities to start. The most common starting points for AI value creation in government today are typically rapid data analysis, intelligent automation, and predictive analytics.

Data analysis. AI feeds on data as whales consume krill: by the ton, in real time, and in big gulps. AI-based systems can make sense of large amounts of data quickly, which translates into reduced wait times, fewer errors, and faster emergency responses. It can also mine deeper insights, identifying underserved populations and creating better customer experiences.21

Intelligent automation. AI can speed up existing tasks and perform jobs beyond human ability. Robert Cardillo, former director of the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency, estimated that without AI, his agency would have needed to hire more than 8 million imagery analysts by 2037, simply to keep up with the flow of satellite intelligence.22

Predictive analytics. Police in Durham, North Carolina, have used NLP to spot otherwise-hidden crime trends and correlations in reports and records, allowing for better predictions and quicker interventions. The effort contributed to a 39 percent drop in violent crime in Durham between 2007 and 2014.23

Showing value to the workforce

When explaining how AI creates value, it’s imperative to include the perspectives of the organization and its workforce. The benefits to the organization are relatively easy to articulate—process automation improves speed and quality; analytics identify investment priorities in areas of utmost need; and predictive tools deliver completely new insights and services.

For the workforce, however, the argument is more nuanced. Staff members must be reassured that AI won’t eliminate their jobs. The strategy should show, as applicable, how AI-based tools such as language translation can enhance their existing roles. Freeing employees from mechanical tasks in favor of more creative, problem-solving, people-facing work creates more value for constituents and can greatly enhance job satisfaction.

In an age of electronic warfare, for example, US Army officers are constantly collecting, analyzing, and classifying unknown radio frequency signals, any which may come from allies, malicious, actors or random sources. How can they manage this overload? The Army created a challenge that drew some 150 teams from industry, research organizations and universities. Models offered by winning teams, based on machine learning, gave the Army a head start in developing a solution to sort through the signal chaos.24 The resulting models have the potential to improve sifting through data with much greater speed and accuracy.25

Governments should build a shared vision of an augmented workplace with the public-sector professionals who will be working alongside these technologies, or incorporating them into their own work. For these professionals, as well as citizens and other stakeholders, this vision must address the ethical considerations of AI applications (see sidebar “Managing ethical issues”) and emphasize its value to the organization and its mission.

Managing ethical issues

In view of the risks and uncertainty associated with AI, many governments are developing and implementing regulatory and ethical frameworks for its implementation.26 The US Department of Defense (DoD), for example, is planning to hire an AI ethicist to guide its development and deployment of AI.27 Other methods being used to meet this challenge include:

Creating privacy and ethics frameworks. Many governments are formalizing their own approach to these risks; the United Kingdom has published an ethics framework to clarify how public entities should treat their data.28

Developing AI toolkits. The toolkit is a collection of tools, guidelines, and principles that helps AI developers consider ethical implications as they develop algorithms for governments. Dubai’s toolkit includes a self-assessment tool that evaluates its AI systems against the city’s ethics standards.29

Mitigating risk and bias. Risk and bias can be diminished by encouraging diversity and inclusion in design teams. Agencies also should train developers, data scientists, and data architects on the importance of ethics relating to AI applications.30 To reduce historical biases in data, it’s important to use training datasets that are diverse in terms of race, gender, ethnicity, and nationality.31 Tools for detecting and correcting bias are evolving rapidly.

Guaranteeing transparency. Agencies should emphasize the creation of algorithms that can enhance transparency and increase trust in those affected. According to a program note by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, “Explainable AI … will be essential if future warfighters are to understand, appropriately trust, and effectively manage an emerging generation of artificially intelligent machine partners.” 32

Scaling as a strategy

After identifying goals for AI, the next step is deciding how to scale it across the organization. The architects of the scaling strategy should always keep in mind the relatively low historical success rate for many large-scale government technology projects.33

Moving AI from pilot to production isn’t a simple matter of installation. It will involve new challenges, both technical and managerial, involving the ongoing cleaning and maintenance of data; integration with a range of systems, platforms, and processes; providing employees with training and experience; and, perhaps, changing the entire operating model of some parts of the organization. Our advice: Break the process into steps or pieces, each clearly articulated to increase the likelihood of success. Test with pilot programs before scaling. And don’t neglect the “capabilities” element of strategy, which, when coupled with an accurate assessment of today’s AI readiness, can identify gaps in current technical and talent resources.

The Central Intelligence Agency’s former director of digital futures, Teresa Smetzer, urged her agency to “start small with incubation, do proofs of concept, evaluate multiple technologies [and] multiple approaches. Learn from that, and then expand on that.”34

Define measures of AI performance and value

The architects must also decide how to measure the value of proposed AI solutions. And if a potential value has been identified, how will it be tracked? On deployment, for example, or usage? The ability to accurately identify value—and plan deployment, sets of metrics, and expectations—will depend, in part, on the maturity and complexity of the AI technology and application. It will also be important to explicitly define performance standards in terms of accuracy, explainability, transparency, and bias.

Success: Strategic choice questions

Managerial

- What specific value will be created by applying AI? Are we improving a current process or allowing the organization to do something new? How will it be measured?

- How do we define success with regard to our workforce? What goals do we set or what actions do we take to increase AI’s value to our employees?

- How will we define and demonstrate success in deployment?

- How can we ensure value is achieved through the ethical usage of AI?

Technical

- How mature or complex are the types of AI we might use? What are the appropriate performance expectations for this type of AI?

- What applications and objectives should a successful pilot have? How do we define success for effective scaling? What timing should be used to implement AI? Which metrics should be used?

Capabilities: What do we need to execute our AI strategy?

“ The intelligence community must develop a more technologically sophisticated and enterprise aware workforce. We must:

- Invest in programs for training and retooling the existing workforce in skills essential to working in an AI-augmented environment.

- Redefine recruitment, compensation, and retention strategies to attract talent with high demand skills.

- Develop and continually expand partnership programs with industry, including internship and externship programs, to increase the number of cleared individuals with relevant skills both in and out of government.”

—US Office of the Director of National Intelligence35

An agency can have the right roadmap, technology, and funding for an AI program and still fail at execution. Different capabilities can help ensure success.

Bridging the AI/data science skills gap

One of the most fundamental questions government leaders must consider is, “Who can build an AI system?” In a Deloitte survey, about 70 percent of public-sector respondents identified a skills gap in meeting the needs of AI projects.36 While the private sector can often attract the right data science talent with competitive compensation, the public sector faces the constraint of relatively limited salary ranges.37

Of course, government work has its own attractions. Many professionals, for example, say they want work that is meaningful and improves the world around them.38 Agency recruiters should emphasize the vital problems they’re fighting and the opportunities to serve society that they’re pursuing through the promise of AI.39

But the constant talent challenge needn’t derail an AI strategy. When recruiting falls short, agencies can acquire expertise in other ways, such as:

- Upskilling and reskilling. Using internal trainers or external partners (such as colleges and universities), agencies can establish training programs to grow thriving AI communities in government.40 For example, the DoD has started offering an AI career path, using a range of digital learning platforms operated by schools and businesses to help personnel keep pace with AI developments in the private sector and give them the knowledge they need to adapt to new roles. These programs are made available across levels and roles, from junior personnel to AI engineers to senior leaders, and combine digital content with tailored instruction from leading experts.41

- AI “guilds.” The UK Government Digital Service (GDS) has created a data science community across multiple agencies. The community organizes conferences and frequent knowledge-sharing events that showcase different approaches agencies are taking toward data science. GDS also runs a data science accelerator program that offers participants the chance to build their skills on an actual government project with guidance from experienced mentors.42

- Competitions and prizes. Government entities also host competitions and partnerships to entice innovative solutions from outside. In March 2019, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services launched a contest, with a US$1.65 million prize for the development of an AI tool that could predict patient health care outcomes.43

- Partnerships. Smaller agencies with limited resources are exploring partnerships with educational institutions and businesses. In conjunction with IBM, for example, the city of Abu Dhabi launched AI training workshops for local government employees. The program was designed to promote a better understanding of AI and its benefits while also improving decision-making skills.44

Agencies should consider whether they will develop AI talent capabilities internally, hire contractors, or use both. On the technical side, agencies must decide whether AI software can be developed in-house, purchased off-the-shelf, or commissioned as custom code. These issues require careful consideration from agency leaders and will vary depending on the agency, its level of ambition, and the maturity of the technology in question.

Building the right foundation

Just as human capabilities are essential to a winning AI strategy, so are the appropriate architectures, infrastructures, data integration, and interoperability abilities. Agencies should test and modify infrastructure before rolling out solutions, of course, but also determine whether their existing data center can manage the expected AI workload. Often the answer is “yes” for a simple proof of concept, but “no” for a production solution. This also raises the issue of how data and cloud strategy will come into play. For example:

- Data: Since AI quality depends on its ability to access high-quality data, data strategy and governance are all-important. The US Department of Health and Human Services’ data strategy includes the consolidation of data repositories into a shareable environment accessible to all authorized users.45 For robust data governance, agencies must clearly define business and system owners and stewards, with clear roles and accountability, as well as guidelines for security, privacy, and compliance issues.

- Cloud: The DoD is preparing a foundation for AI with a US$10 billion contract that aims to move its computing systems into the cloud.46 The Pentagon says that this will help it inject artificial intelligence into its data analysis, reaping benefits such as providing soldiers with real-time data during missions.47

Cloud and data strategies are essentially universal issues for AI deployment. Others, such as necessary organizational changes or the need to modernize individual systems, will be specific to each agency and the ambition, applications, and value it pursues.

Capabilities: Strategic choice questions

Managerial

- What are the skills needed to implement AI applications? What will scaling require? Is the workforce adequately trained? If not, how can we recruit talent with the necessary knowledge and expertise?

- What will the workforce need to accept AI implementation and training?

- How can we recruit AI talent? What advantages could be achieved by partnering with other entities?

- What academic and industry partners can we use?

- What organizational or cultural changes will be necessary?

Technical

- What specific tools and platforms can be used for this AI solution?

- What data governance and modern data architectures will it need?

- What technology and data issues must we face?

- What other process changes will be required?

Creating the management systems

“ The DoD will identify and implement new organizational approaches, establish key AI building blocks and standards, develop and attract AI talent, and introduce new operational models that will enable DoD to take advantage of AI systematically at enterprise scale.”—US Department of Defense48

Some leaders breathe a sigh of relief once their roadmap has the necessary AI technologies, processes, capabilities, and funding—but that’s often part of the reason it fails. Not enough attention is typically focused on successfully developing management systems to validate specific initiatives (including cost/benefit analyses), evangelize the project to stakeholders and employees, scale projects from pilot to implementation, and track performance.

Good change management and governance protocols are important. AI is likely to be disruptive to organizations and governments both due to its novelty and its potential complexity. Reviewing all these protocols is beyond the scope of this paper, although we’ve already alluded to the importance of building a compelling story and value proposition for the workforce and other stakeholders. For governance, we touched upon the need to establish and track performance measures—and to revisit them regularly.

This section focuses on some of the emerging structures and systems needed to bring AI strategies to fruition.

Establish an AI operating model

One common best practice for a complex technology project is to establish a center of excellence (CoE) or “hub.” Centers of excellence are communities of specialists built around a topic or technology that develop best practices, build use-case solutions, provide training, and share resources and knowledge.

CoEs draw technology and business stakeholders together for a common purpose, and they in effect partner to identify and prioritize use cases, develop solutions, create innovations, and share knowledge. For example, DoD chief date officer Michael Conlin established the Joint Artificial Intelligence Center (JAIC) with the overarching goal of accelerating the delivery of AIenabled capabilities, scaling AI departmentwide, and synchronizing DoD AI activities to expand Joint Force advantages.49 Similarly, the Department of Veterans Affairs’ first director of artificial intelligence, Dr. Gil Alterovitz, is leading an effort to connect the department with AI experts in academia and industry.50

Develop governance frameworks

JAIC, again, is more than a simple CoE; it’s a critical element of AI governance. Governance challenges must be addressed if change management is to be effective as AI is adopted across mission areas and back-office operations. And since data-sharing is a vital element in achieving AI’s full impact, explicit governance models must address when and how data will be shared, and how they will be protected. But these challenges might be typical of any digital project; AI brings its own unique governance challenges.

Government agencies increasingly use algorithms to make decisions—to assess the risk of crime, allocate energy resources, choose the right jobs for the unemployed, and determine whether a person is eligible for benefits.51 To instill confidence and trust in AI-based systems, well-defined governance structures must explain how algorithms work and tackle issues of bias and discrimination.52

Several nations are establishing coordinating agencies and working groups to govern AI. Among these is the United Kingdom’s Centre for Data Ethics and Innovation, which will advise the government on how data-driven technologies such as AI should be governed, help regulators support responsible innovation, and build a trustworthy system of governance.53 Singapore has published an AI governance framework to help organizations align internal structures and policies in a way that encourages the development of AI in a fair, transparent, and explainable manner.54

Establish AI deployment structures

Another challenge is thinking through how to advance the many pieces of a project from design through execution. One common trap is “pilot purgatory,” in which projects fail to scale. The reasons for this are varied, but often fall into one of these categories:

- Pilots are designed narrowly, and thus more easily achieved, but do not have much of an impact on a wider audience. Impact is what generates buy-in.

- A pilot generates limited returns, despite considerable expenditure of financial and human capital. Stakeholders become reluctant to move it to implementation.

- Scaling AI pilots requires adapting new technologies and different ways of working, which some workers inevitably resist.

One way to avoid such potholes is to borrow from the studies of behavioral scientists and build quick wins into the process. At the start of your AI journey, focus resources on quick payoffs rather than more lengthy transformative projects. They can be relatively easy to execute and generate high mission value. Further, before launching pilots, agencies should prioritize business issues and subject potential AI solutions to a cost-benefit analysis. Then pilots can be launched to see if the hypothetical benefits can be achieved.

Establish structures and systems for scaling

For public agencies, processes that integrate AI within existing computational infrastructures remain a challenge.55 While solutions vary, four areas often require significant new systems, structures, or leadership. An AI strategy should be sure to carefully consider whether changes will be required in:

- Technical infrastructure. AI is not part of most agencies’ IT stack, but it should be. To deploy AI applications, agencies require high-bandwidth, low-latency, and flexible architectures. And since data is the food that feeds the AI beast, special care is needed to ensure existing and forthcoming data is cleansed to remove inaccurate, incomplete, improperly formatted, and duplicated data.56

- Organization and team structure. AI can be one of the most effective antidotes to the siloed organization. To generate the most benefit, AI systems rewrite processes and integrate data from across the organization. AI implementation should involve cross-functional teams from the start. Representation from many teams empowers workers to make decisions based on fast-flowing data.

- Talent management. As noted above, AI-driven organizations need to bring in new capabilities but also need to train current workers. New retention strategies will be needed, compensation will have to be redefined, and partnerships will need to be developed.57

- Culture. Existing culture often hinders efforts to infuse AI into the organization. Agencies should inculcate a data-driven culture by incentivizing data-based experimentation, appointing informed change agents, and appealing to influential leaders to become sponsors of AI initiatives in the organization.58

Ensure data quality for AI applications

Data is often stored in a variety of formats, in multiple data centers and in duplicate copies. If federal information isn’t current, complete, consistent, and accurate, AI might make erroneous or biased decisions. All agencies should ensure their data is of high quality and that their AI systems have been trained, tested, and refined.59

JAIC is partnering with the National Security Agency, the US Cyber Command, and the DoD’s cybersecurity vendors to streamline and standardize data collection as a foundation for AI-based cyber tools. This standardized data can be used to create algorithms that can detect cyberattacks, map networks, and monitor user activity.60

Management systems: Strategic choice questions

Managerial

- What’s our operating model? Who will be responsible for AI? How should we track performance measures and indicators of AI’s impact?

- What communication strategies should we use to gain the trust of employees, external partners, media, and the public?

- What change management skills do we need?

Technical

- How can we manage AI risks?

- How can we manage the piloting and scaling of AI across different departments?

- How should AI resources be developed, accessed, housed, allocated, and managed?

Conclusion

As with the introduction of electricity at the beginning of the 20th century and the internet more recently, AI can fundamentally change how we live and work. As key developers and users of AI-based systems, government agencies have a special responsibility to consider not only how it can be used to make work more productive and innovative, but also to think about its potential effects, positive and negative, on society at large.

Agencies should begin the AI journey with a strategy that entwines technology capabilities with mission objectives; creates a clear methodology for decision-making; sets guardrails and objectives for implementation; and emphasizes transparency, accountability, and collaboration. Government leaders are already acting on AI investments. A clear, holistic strategy will help them ensure their AI programs are more likely to achieve their potential for the mission, the workforce, and citizens today and tomorrow.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.

Explore Artificial Intelligence in government

-

Artificial intelligence in government Collection

-

Government executives on AI Article5 years ago

-

The rise of data and AI ethics Article5 years ago

-

AI-augmented human services Article5 years ago

-

AI-augmented cybersecurity Article7 years ago

-

AI-augmented government Article5 years ago