Service design in government How design thinking principles can bolster mission effectiveness, productivity, and customer satisfaction

9 minute read

07 June 2019

Service design combines principles of customer experience and business process design to help public sector agencies improve three critical tasks: mission effectiveness, productivity, and customer satisfaction.

When patients began trickling away to commercial drug stores, a government pharmacy network tried a customer experience cure. But the trickle continued, then grew to a steady flow. The network was hemorrhaging money.

The pharmacies were paying upwards of 50 percent more for every prescription filled outside their network. Even when patients were buying their medicine elsewhere, the network still had to pay for their pharmacy network staff and real estate.

Learn more

Explore the Government and public services collection

Subscribe to receive related content from Deloitte Insights

Pharmacy operating costs were swallowing a quarter of the medical budget that had to cover a full range of medical care for their patients.

Drug spending outside the network had to come down.

It wasn’t as though the pharmacies hadn’t tried to entice customers back. They added displays in waiting rooms showing time estimates for checking in and for filling prescriptions. Pharmacy staff monitored wait times on their computers and attempted to reduce them. But it wasn’t enough.

Patients continued voting with their feet.

The pharmacy network’s customer experience needed drastic improvement, and the root causes for patients’ pain appeared to run deeper than pharmacy checkout counters. So, network leaders kicked off a full-scale pharmacy service redesign. It began with a broad study of patients’ habits, motivations, and expectations and examined how they moved end-to-end through pharmacy services. Researchers surveyed 1,000+ patients and a broad range of health care providers, conducting direct interviews with patients in waiting rooms and with pharmacy staff.

The results caught the pharmacy team by surprise. It wasn’t waiting for prescriptions that most irritated patients. It was that at the end of the wait, the pharmacies often didn’t have the medications they needed.

The network had been treating the wrong problem.

Rx for the real problem

The pharmacy team’s prescription for curing patients’ real complaint—unavailable medications —took effect far from the waiting areas. Treating it meant recombining and improving data streams so staff could track drug availability, view historical and real-time prescription demand data, and track supply performance.

Using a new inventory data tool, pharmacy staff aligned the amounts and types of medication they keep on hand with actual patient demand. Now they are able to prepare for seasonal shifts and changes in available medicines, so they have enough of the right drugs on hand even when demand peaks.

At the pilot test sites, medication availability increased 25 percent. It led to a 46 percent increase in patients served within 30 minutes at one pharmacy, and lifted service quality scores by 22 percent at another.

Pharmacy staff no longer over-order drugs that sit on shelves beyond their expiration dates or underorder them, driving empty-handed patients to retail drug stores. Adding effective drug data and logistics to a positive interaction at the pharmacy counter ensures their prescriptions are filled and keeps pharmacy customers coming back.

Beyond customer experience

Many companies and government agencies have undertaken customer experience (CX) improvements.1 Until recently, however, these efforts have focused purely on the customer interactions. Few have combined CX with business process reengineering to design—or, as is more often the case in the world of government legacy systems, redesign—services more broadly.

Service design uniquely considers how the “front-stage” experience of the patient, traveler, business partner, or other end user is orchestrated with the “back-stage” capabilities and sequencing of activities to enhance that experience.

Service design uniquely considers how the “front-stage” experience of the patient, traveler, business partner, or other end user is orchestrated with the “back-stage” capabilities and sequencing of activities to enable and enhance that experience (figure 1). It is an inherently holistic and systems-oriented approach to problem-solving that involves planning and organizing people, processes, and technologies, along with the infrastructure to improve the quality of interactions between organizations and the audience they are serving.

CX-minded providers often envision the “optimal experience” for their customers, but unless the ecosystem of supporting processes and systems is optimized to deliver that experience, any plans for improvement will ultimately fail.

A mandate for service design

Service design isn’t just a promising practice for improving mission delivery, productivity, and customer satisfaction. It’s highlighted in the President’s Management Agenda, which calls it out as a tool for pursuing more effective customer interaction and engagement. The agenda includes a cross-agency priority goal, “improving customer experience with federal services,” that covers more than two dozen high-impact service provider (HISP) programs in more than a dozen departments.2

A new section in the Office of Management and Budget Circular A-11 includes service design in a list of core functions to be used by HISPs in managing customer experience:

Service design: Adopting a customer-focused approach to the implementation of services, involving and engaging customers in iterative development, leveraging digital technologies and leading practices to deliver more efficient and effective touchpoints, and sharing lessons learned across government3

The White House Government Effectiveness Advanced Research Center aims to be an incubator for innovative solutions to government’s biggest problems. Among its charges is to create holistic and systems-oriented solutions by bringing together experts in economics, computer science, and design thinking to reimagine how citizens interact with government and how government delivers services—in short, to redesign the delivery of its services.

Remaking poorly performing services doesn’t just help a government program or agency reap effectiveness and efficiency dividends and improve customer satisfaction; it also helps it comply with White House mandates. HISPs, especially, must meet customer experience metrics, which are then publicly reported. Service design is one of the tools to help these programs meet their goals.

Public service redesign in action

The pharmacy initiative described earlier displays the hallmarks of service design:

- It made impactful improvements in customer experience through informed, deep understanding of users and of the current state of the service provided.

- It mapped the immediate and supporting processes and systems to demonstrate how they influenced and potentially limited current capabilities and could be changed to enable potential improvements.

- It thoroughly accounted for and analyzed staff, manager, stakeholder, and customer points of view to reimagine the service.

- It shifted the focus from delivering on time to delivering value.

All this involved redesigning pharmacies’ structure, metrics, culture, and processes. The pharmacies’ experience illustrates the importance of examining first- and second-order processes when attempting to transform customer experience. Often, the fix is far removed from the customer, and nothing truly will change until the processes and technologies creating poor experiences are addressed.

Furthering USPTO’s core mission

Service design can help heal other government ills, too. For example, when the constituencies served change or one segment grows faster than another, an organization might lose track of users’ needs. Service design dives into the demographics and experiences of new or changing customers, identifies the root causes of service shortcomings, and prescribes integrated front-end and back-end solutions that support an optimal experience for users.

Case in point: the US Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO). As Jill Leyden Wolf, customer experience administrator for trademarks at USPTO, explains, “We have a growing segment of do-it-yourselfers. About 30 to 40 percent of our applicants are coming to access our services on the trademark side without attorneys. That could be a mom-and-pop shop; it could be a startup without legal counsel yet coming to us to access our services, but they don’t have a baseline understanding of what trademarks really are.”4 The same could be said for new users of the even more complex patent process.

Accountable for much of the country’s job growth and innovation, this group of mostly first-time applicants arguably have the greatest need for patent and trademark protection. Without lawyers to show them the ropes, most first-timers didn’t know how to begin the complex trademark or patent application processes or how to find or fill out the right forms on USPTO.gov. These customers were the most likely to give up on the application process, depriving themselves of protection and the agency of fees. They also were the biggest users of the call center, which added significant cost for USPTO.5 The struggles of do-it-yourselfers were not unknown, but until the customer journey of the novice user was analyzed using service design methods and tools, it was difficult for USPTO to see clearly how those struggles were impacting the agency’s mission goals and bottom line or how best to improve on an underoptimized system.

USPTO applied service design, backtracking to learn more about every step of new users’ experience. Those lessons led the agency to reorganize its website and hire writers to simplify and clarify its language. It adopted quick, easy fixes, such as a cheat sheet on how to fill forms, cluing in users on form idiosyncrasies and how to handle them. And, to mimic a more YouTube-like experience that customers were accustomed to, it corralled all its how-to videos in one place.

Redirecting resources where they belong most

Citizens all too often find themselves frustrated because they must navigate disconnected, inconvenient systems to access government services. Employees resent being pulled from their work to assist users of these poorly designed processes. That’s exactly what was happening in the US Customs and Border Protection’s (CBP) Global Entry Program.

Global Entry was designed to speed prevetted international fliers through airports, both saving trusted travelers precious time at the airport while freeing the time of security and customs officers to focus more on screening higher-risk passengers. It seemed like a customer-service slam-dunk. But it wasn’t taking off. Service design prompted traveler and employee listening sessions that showed while the Global Entry service at airports was enticing, the Global Entry enrollment centers were chokepoints.

Provisionally approved Global Entry applicants had to travel to an enrollment center for an in-person interview to complete the process. But making interview appointments often took months and getting to them could entail a trip of hundreds of miles.

To smoothen the process, CBP designed Enrollment on Arrival (EOA), an alternative interview process conducted at airport customs booths when customers were returning to the United States.

Since its inception in 2017, EOA has expanded to 47 major international airports, with over 70,000 enrollments in FY18, resulting in added convenience for Global Entry applicants and saving CBP thousands of officer hours over each traveler’s five-year Global Entry membership.6

Reducing backlogs

Regulatory agencies don’t have direct customers in the commercial sense, but they, and the citizens they protect, have as much to gain from service design as commercial organizations. Take the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB), which supervises financial institutions to help ensure they don’t engage in risky practices.

When the bureau came under scrutiny from its inspector general in 2014, improving the operational efficiency of supervision was flagged as a management challenge that, left unaddressed, would most likely hinder the bureau’s ability to achieve its strategic objectives.7

At the time, CFPB’s examination process was bogged down under the weight of multiple, duplicative reviews, unclear authority, and mountains of conflicting edits, leading to delays in the issuance of examination reports. According to CFPB’s inspector general: “[T]he CFPB had not met its goals for the timely issuance of examination reports, and a considerable number of draft examination reports had not been issued,” resulting in “delays in the issuance of examination reports that can leave supervised institutions uncertain about the CFPB’s feedback on the effectiveness of the institutions’ compliance programs or processes, which could delay the implementation of required corrective actions.”8

Unsticking exams and reports proved relatively inexpensive—as often is true with service design projects—but it wasn’t easy. CFPB had to delicately realign final decision-making power from key stakeholders and delegate it to fewer that were closer to the frontlines. A new triage function expedited reviews for lower-risk examinations. Templates made reports faster to write and improved quality. Setting time limits and enforcing them for each step in the examination and reporting process made expectations and responsibility clear.9

By realigning front- and back-end processes, CFPB was able to improve the effectiveness and efficiency of the exam process. The number of exams exceeding time limits stopped increasing. A rising proportion of exams qualified for expedited regional and headquarters review, leaving extra time to focus on higher-risk and more complex cases. Relations between field examiners and leadership also improved.

Targeting the biggest service design returns

Backlogs are just one ubiquitous government problem that service design addresses. One could argue that it’s hard to come up with a government service that wouldn’t benefit significantly from service design. Widespread public sector adoption of customer experience initiatives shows that government program leaders are willing to embrace techniques to improve service to citizens. Service design can help accomplish that while also delivering efficiency gains and increased mission effectiveness to ensure better experiences will stick.

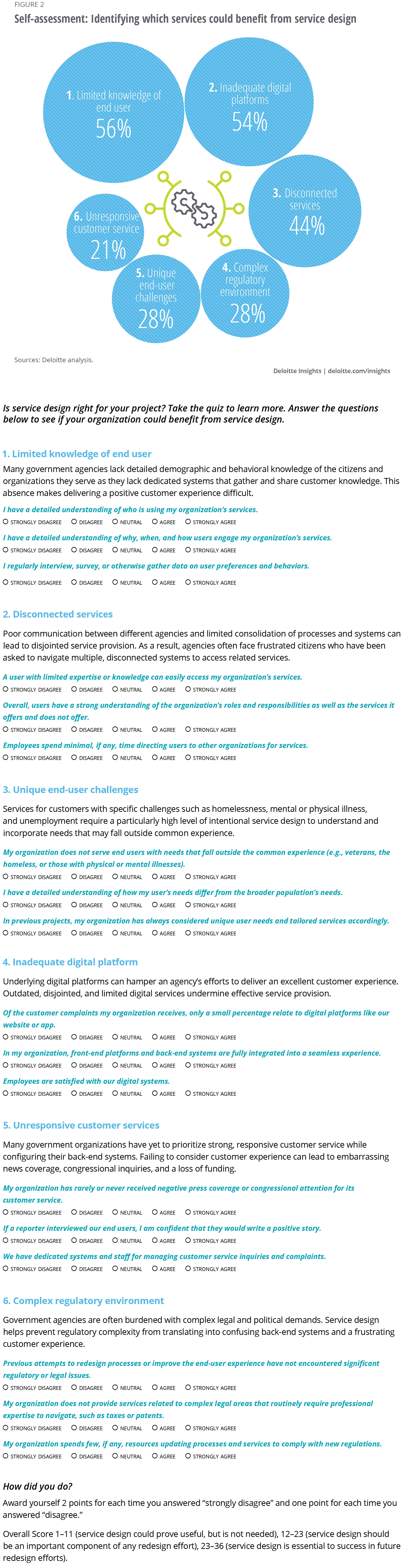

Public sector organizations should target programs where service design will deliver the biggest return on investment. Deloitte’s Government and Public Services Customer Strategy and Applied Design team reviewed 39 case studies of successful government service design projects to develop indicators of service design opportunities (see sidebar, “Self-assessment: Identifying which services could benefit from service design.”). Six showed up again and again:

Limited knowledge of end user. Many government agencies lack detailed demographic and behavioral knowledge of the citizens and organizations they serve. Without dedicated systems that gather, analyze, and share customer knowledge, delivering a positive customer experience is difficult.

Disconnected services. Poor communication between different agencies and limited consolidation of processes and systems within the same agency can lead to disjointed service provision. As a result, agencies often face frustrated citizens who have been asked to navigate multiple, disconnected systems to access related services.

Unique end-user challenges. Services for customers with specific challenges such as homelessness, mental or physical illness, and unemployment require a particularly high level of service design to understand and incorporate needs that may fall outside the common experience.

Inadequate digital platforms. Underlying digital platforms can hamper an agency’s efforts to deliver an excellent customer experience. Outdated, disjointed, and limited digital services make effective service provision nearly impossible.

Unresponsive customer service. Many government organizations fail to consider how back-end systems impact their ability to provide responsive customer service. A poor customer experience can lead to embarrassing news coverage, congressional inquiries, and a loss of funding.

Complex regulatory environment. Government agencies are often burdened with complex legal and political demands. Service design helps prevent regulatory complexity from translating into confusing back-end systems and a frustrating customer experience.

Looking ahead

Service design projects, by their very nature, require leaders to embark on a journey of discovery, leaving behind preconceived notions about why things are the way they are, and seeing things anew from the customer’s perspective. To be able to succeed, leaders must embrace the process and, through it, the opportunities it reveals.

As more agencies embrace service design—both to comply with the OMB mandate and as a means of furthering their own mission objectives and organizational performance—project designs and/or procurement approaches will need to be revisited and updated to reflect the inherent uncertainty about the nature of the solutions that will emerge from the process.

SELF-ASSESSMENT: IDENTIFYING WHICH SERVICES COULD BENEFIT FROM SERVICE DESIGN

The Government and Public Services Customer Strategy and Applied Design team analyzed case studies featuring service design in the public sector to identify indicators that suggest that a project represents a strong opportunity for service design. Through the analysis of the case studies, the team identified six service design indicators that point to a potential opportunity for service design.

Focus on government and customer experience

-

Government & Public Services Collection

-

Case Studies: Customer experience in government Interactive8 years ago

-

Flying smarter with IoT Article5 years ago

-

Government backlog reduction Article5 years ago

-

Making micromobility work for citizens, cities, and service providers Article5 years ago

-

Nudging compliance in government Article6 years ago