Employees as customers: Reimagining the employee experience in government has been saved

Employees as customers: Reimagining the employee experience in government How design thinking and customer experience tools can help attract and engage public servants

01 June 2016

Max Meyers United States

Max Meyers United States Hannah Roth United States

Hannah Roth United States Eric Niu United States

Eric Niu United States David A. Dye, PhD United States

David A. Dye, PhD United States

As governments look to build a workforce able to tackle the tough, interconnected challenges of the 21st century, strengthening the government employee experience is particularly critical. By treating employees as customers, agencies have the chance to improve both the employee experience and their own ability to execute their mission.

Viewing employees through a customer lens

When Chris Cruz became the deputy CIO for the State of California, the California Health Care Services’ IT department had a 34 percent job vacancy rate. Now, it is 5 percent. Where many executives might double down on a given process or policy—recruitment efforts or retention incentives, for example—Cruz honed in on specific issues for his workforce. The difference, he says, was the adoption of an aggressive telecommuting policy (“You have to work around [employees’] schedules”) and substantial training opportunities in new technologies.1

Cruz’s success points to a critical insight: Engaging an organization’s people is ultimately about removing pain points and distractions at work to create a better experience. As John Kembel of Stanford’s d.school observes, “Most failures in industry are not that people can’t solve problems; it’s that they’re not always great at identifying the right problems.”2

“Most failures in industry are not that people can’t solve problems; it’s that they’re not always great at identifying the right problems.” —John Kembel, Stanford d.school

Recently, fields like consumer marketing and digital design have led the way in developing more advanced approaches to understanding and addressing the needs of their customers and users—what many refer to as “design thinking.” Technology companies in emerging markets, for example, improve products and increase adoption by studying how different cultures use social media platforms.3 Some large companies like IBM have even hired thousands of designers to apply this same approach—“ethnographic design”—to influence product development for differing customer segments.4 In each of these cases, design helps to marry business strategy and people’s needs.

Thinking of employees in the same way—as customers—may similarly improve both key business outcomes and employees’ experience. But for many employees, the experience they have as consumers or technology users ends when they come to work; only 31 percent of companies say that they measure employee experience, compared to 81 percent that report they analyze customer experience.5 “If we have a Customer Experience Group, why not create an Employee Experience Group?” asks Mark Levy, the global head of Employee Experience at Airbnb.6 The online travel company, in fact, recently converted its traditional human resources (HR) groups into one organization tasked with tackling distractions—ranging from meal options to career programs—that can keep employees from bringing to life the company’s mission and values.

Strengthening the employee experience is particularly critical for government agencies to be able to realize their mission and values today. Federal scores for satisfaction and commitment are stagnant, hovering just under 60 percent over the past five years and consistently lagging the private sector.7 And as with customers, the employee experience brands government service for potential employees as well—more graduates of the top 15 public affairs schools now choose to enter nonprofit or private sector than government jobs.8 As agencies look to build a workforce able to tackle the tough, interconnected challenges of the 21st century, federal leaders need better tools to address hard realities like low employee engagement, difficulty recruiting new talent, and cumbersome processes for managing employees.

A customer “lens” offers the potential to help agencies navigate between doing what is simply interesting, new, or easy and what will actually make a meaningful, positive impact on an employee’s experience and career satisfaction. This study examines ways that government agencies could adapt the key principles of experience design to treat employees as customers, and explores how this approach can transform the employee journey for public servants.

A different approach: Focus on the employee experience

Like customers, today’s workforce has greater awareness of and access to other opportunities, driving employers to rethink how they develop or maintain a competitive position in today’s talent market. The prevailing view of talent management resembles a supply chain, with an on-ramp for hires and an off-ramp for retirees—and the tools to support this life cycle tend to reflect the ideas found in manufacturing: standardization and scale. But just as consumer products have evolved from using mass marketing and “push” advertising, organizations today are moving beyond a “one-size-fits-all” approach to their workforce.

A more differentiated and holistic approach, however, may require overhauling how organizations manage people today. Traditional HR solutions are structured around programs or processes to administer pay/benefits, source and train workers, manage work, or limit risk in the workplace—and making them better has emphasized scaling “leading practices” for similar functions.9 But, as companies’ recent focus on culture and engagement suggests,10 realizing the full potential of the workforce may require more cross-cutting, holistic solutions tailored to a specific business context or outcome. As Laszlo Bock, head of Google’s People Operations, notes: “We all have our opinions and case studies, but there is precious little scientific certainty around how to build great work environments, cultivate high-performing teams, maximize productivity, or enhance happiness.”11

Adapting customer experience and design thinking principles (see The Customer Experience Approach) to employees offers a blueprint for more individualized services; it maps the range of experiences at critical points, and uses the insights to design human capital strategies that help agencies better achieve their missions. Effectively doing so requires that leaders embrace different perspectives on employees, careers, and HR service delivery.

A differentiated view of employees

What employees need to simplify or enhance their work may be different depending on what kind of work they do, their life outside of work, or what motivates them as a person. HR organizations typically try to understand these factors by grouping employees by demographics, roles, or performance levels. However, surface characteristics may mask deeper traits, values, and behaviors that could offer leaders more actionable insights. Agencies should instead “look at employees as ‘consumers of work,’” says John Boudreau, author of Transformative HR. “Marketing and consumer behavior have a lot to tell us about how we understand employee segments.”12

Effective employee segmentation brings together a variety of factors, using personas and stories to create empathy with—and insight into—the human dynamics of employees that drive engagement and productivity. For example, Starbucks famously took a customer “action segmentation” approach to understand what attracted, motivated, and retained employees. Based on the results, they found three clusters: “skiers,” who work mainly to support other passions; “artists,” who desire a community-oriented and socially responsible employer; and “careerists,” who want long-term career advancement within the company.13 The clusters helped managers better tailor programs to multiple sets of employee needs, as well as enabling the company to understand what needs span groups—such as schedule flexibility or tuition assistance.

A broad view of career events

Employees’ satisfaction, commitment, and mission engagement ultimately reflect the sum of positive and negative experiences at critical moments throughout their careers. Studying people at work to understand when and where employees experience motivation, confusion, or challenges may help agencies better understand critical moments along employees’ career journey—what designers call “journey mapping”—and better design services to meet these needs. While an employee may cite a single factor like compensation or career progression on an exit survey as reasons for leaving, for example, issues such as pay or promotion may actually be a proxy for other unmet needs.

The Federal Labor Relations Authority (FLRA) faced exactly this challenge. In 2009, only 55 percent of employees were satisfied with pay—the lowest-ranked of all small agencies, despite higher-than-average pay for their professional/legal workforce.14 Carol Waller Pope, newly appointed as chairman, tackled the issue head-on, addressing classification errors around administrative and professional pay that had been raised. Employees took note, and satisfaction jumped to 77 percent—which made the next year’s drop surprising. “It can be frustrating,” says Pope. “You try to address issues, and there’s still dissatisfaction.” But she kept experimenting and broadened her scope. Inspired by a newspaper article on overall federal pay, she published agency pay ranges by quartile in the agency’s newsletter—and saw satisfaction rise. Pope expanded the experiment to performance recognition, publishing ratings data, and interviewing employees to understand the perception of recognition versus pay. Plus, she personally reinstituted a regular forum for the workforce segment with the lowest engagement scores around pay. Discussions on pay uncovered a desire for training to increase qualification for better-paying jobs—and prompted FLRA to invest in a subscription to an online professional skills training platform and career counseling seminars. Through observation, listening, and experimentation, Pope found that satisfaction with pay was heavily tied to trust, recognition, and career opportunities—and saw FLRA rise to be the top-ranked small agency in the category by addressing these issues.15

A digital perspective on service design

A key accelerator for better customer experience and insights in the past decade has been new technology—and digital tools could similarly reshape the experience of employees. Becoming digital is not just about new or more technology, but about platforms that change the way work is done, how workers interact, and the way the workplace is structured. Just as governments are exploring how apps and user interface design can improve how citizens access public services, agencies should turn the same capabilities inward to help employees access knowledge, tools, and support at critical moments in the journey. Outdated and poorly designed technologies increase the time it takes to get the job done, creating an environment where employees feel frustrated and unproductive. More advanced tools offer to help organizations both simplify the journey to focus on these moments—and personalize how they address the myriad motivations or preferences in play.

Transport for London (TfL), one of the world’s largest transit agencies, recently embarked on this journey with their “fit for the future” initiative to deploy digital tools and scale back administrative tasks. Familiar with customer journey mapping, TfL began by mapping daily activities and identifying where distractions made it harder for employees to engage customers or create a healthy, safe environment. At Victoria Station, for example, they found that employees had to manually check in arriving coaches by sending a sheet up the “daisy rope” to the control center, and that customer service agents (CSAs) operated based on a paper schedule they received each morning16—opportunities to simplify and enhance employees’ work. Similarly, in another department, TfL built a crowdsourcing app to report non-urgent issues in the station environment, modeled after an app used to take pictures of potholes and document it in the city’s work system. “So you come across a non-urgent fault on the train line like some graffiti,” explains Marc Woods, a senior business analyst for TfL. “You take a photo of it, you fill out a couple questions and things, and that gets sent through and prioritized.”17

By tying digital tools to service design, TfL was able to both create more time for employees to focus on what matters to them, and empower them to solve their own challenges—and HR software today is starting to formalize and scale similar capabilities to simplify or improve work. Described as a shift to “systems of engagement” designed to support employee insights and interactions, today’s applications are quickly advancing beyond serving only as “systems of record” that help HR managers capture the information needed to administer end-to-end talent processes.18 Applications like Slack are even reimagining modern categories like email or file sharing—and themselves reinforce a brand and experience. As Greg Godbout, co-founder of 18F, recalls, “I can’t tell you how many people we hired who said, ‘I heard you guys were using Slack.’ It just meant that we were cutting-edge.”19

Ideas in action: Reimagining the employee journey

Thinking of employees as customers not only changes how government leaders design talent solutions, but also reframes the employee career model (figure 2). Each of the critical moments identified—and the positive or negative experience an employee has in that moment—ultimately impacts a set of employee decisions about the work and the organization: the decision to join, to contribute, to improve, and to transition. Applying customer experience tools—segmentation, journey mapping, human-centered service design, personalization, and co-creation—could help influence these decisions. The sections below explore these ideas in action, illustrating how these tools and principles can reshape traditional talent solutions and HR services.

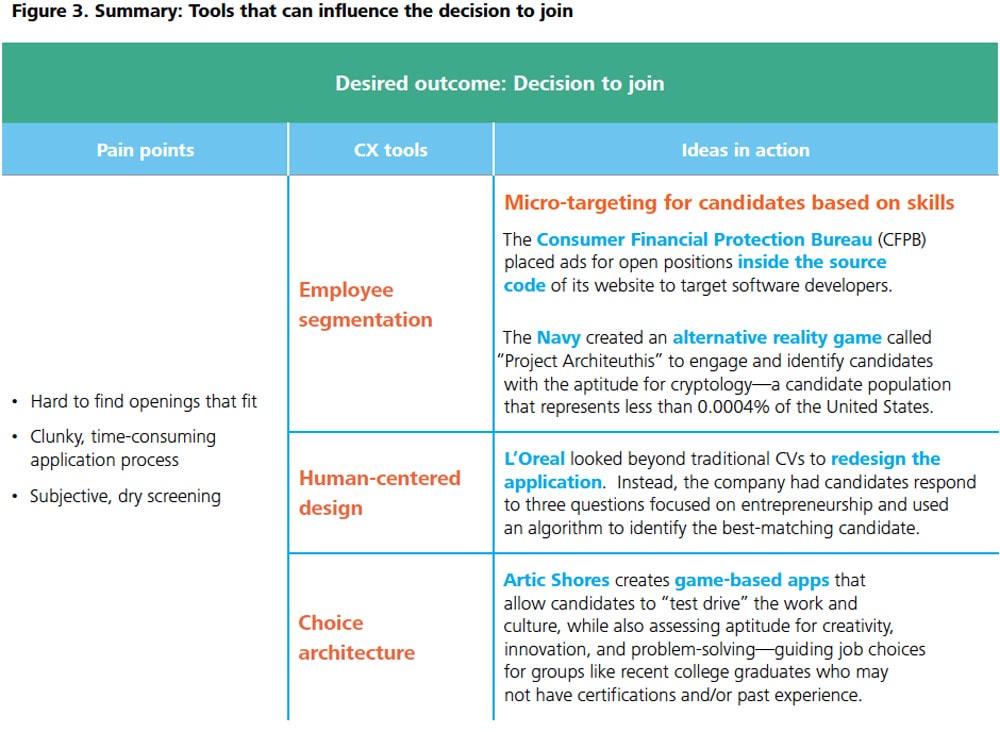

The decision to join

Twenty-five percent of graduating college students rank government as one of the top three industries in which they would want to work, yet a much smaller percentage decide to actually launch a career in the public sector.20 In some cases, today’s talent market offers more options for socially minded or highly skilled recruits—an expanding ecosystem of nonprofits and social enterprises offer more diverse pathways for service, and a rising cadre of technology organizations place a premium on analytical and digital skills.21

In today’s budgetary environment, agencies often have limited ability to directly address these challenges by offering recruitment incentives or cutting-edge environments. Design tools could offset these handicaps by addressing current pain points in today’s candidate experience in three important ways, by helping candidates more easily:

- Find opportunities that match their interest

- Apply for openings

- Gauge their fit

Better match interest to openings

First, today’s approach of recruiting—asking candidates to browse a long list to identify if there is an opening that matches their interest and qualifications—may make it hard to find jobs. The intelligence community recently took a step toward addressing this pain point with the launch of IntelligenceCareers.com, which includes a 13-question “Job Exploration Tool” to help identify a specific job or category match.22 But such capabilities are still niche for agencies, and candidates with an interest in government often gravitate toward the more targeted experience offered by modern recruiting sites—as suggested by a PACE survey that found that candidates were more likely to use LinkedIn (17.3 percent), CareerBuilder (15.5 percent) or Monster (14.5 percent) over the USAJOBS.gov website (8.0 percent) to find jobs within the federal government.23

The US Navy has created an alternate reality game (ARG) called “Project Architeuthis” to engage and identify candidates with the aptitude for cryptology.

To better market opportunities, agencies could start by examining how or where a candidate discovers an opportunity—using segmentation to understand how jobs align to the needs, interests, and capabilities of specific groups of candidates. Just as merchants tailor marketing plans and activities to customer segments based on the different needs of each, agencies could adopt tailored recruitment strategies for different workforce segments, tapping into activities or interactions that align with what the role requires. For example, Google analyzes search habits to connect with tech talent, identifying when someone has a habit of using the platform as a programming resource and inviting them to complete a coding challenge.24 Agencies might use a similar strategy to locate hard-to-find skills—in the case of the intelligence community, for example, perhaps using rate or volume of data consumption to flag those with potential for analysis, which requires absorbing large amounts of information and quickly analyzing significance/risks.25

Some agencies have already begun to market opportunities more incisively based on role or segment. The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) has placed ads for open positions inside the source code of its website where developers often browse.26 The US Navy has created an alternate reality game (ARG) called “Project Architeuthis” to engage and identify candidates with the aptitude for cryptology. This social media-based competition reached more than 100,000 individuals and was featured on over 50 media outlets, ultimately helping the Navy exceed its goal for new cryptology recruits—a population that represents less than 0.0004 percent of the United States.27

Simplify the application process

More than half the candidates who find the application process difficult develop a negative impression of a company’s products and services28—and agencies could begin to shape that experience in simple ways like writing clear and realistic job postings. USAJobs’ recent makeover starts to tackle some of this, mapping the user journey during the application to identify and fix pain points—like allowing applicants to track progress to completion or finish the application in more than one sitting.29 But beyond simply making it easier to identify and apply to jobs, agencies could also go further in reimagining traditional hiring elements like the résumé.30 Tired of drowning under paperwork, L’Oréal, for example, opted instead to have the 33,000 applicants within their China market answer three simple, open-ended questions, using an algorithm to analyze responses—and found that, often, the candidate chosen might have been overlooked if he or she had only submitted a résumé. Emerging cloud-based apps like Plum Voice or HireVue use similar tools—including video interviewing that builds in text analytics to also serve as a screening tool—to gain 25 percent faster cycle time, 29 percent less turnover, and 13 percent more top performers.31

More accurately gauge fit

Just as customers might test a product, tools like gamification can help candidates and agencies see how and select where they might fit with the work or culture—particularly for hard-to-assess groups like recent college graduates, where past experience or certifications may not be as helpful. “Early careers recruitment has hardly changed over the years,” notes Robert Newry, co-founder of UK-based Artic Shores. “A games-based app provides an easy way for candidates of all backgrounds to show if they have what it takes.” 32 His company has produced several apps to do so, including “Firefly Freedom”—an app that collects over 3,000 data points in a 20–30-minute session to help analyze aptitude for creativity, innovation, and problem-solving.

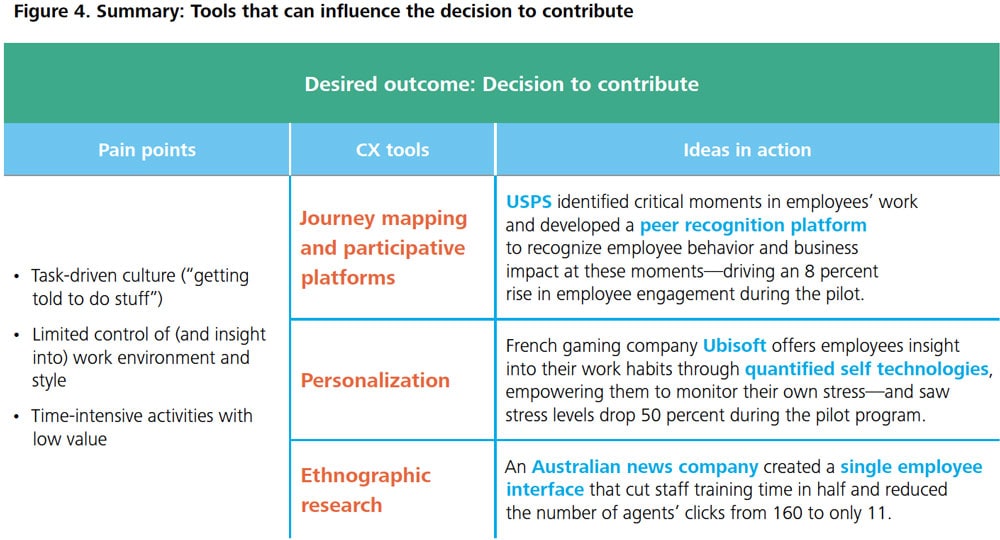

The decision to contribute

“Employee engagement drives performance and is closely tied to mission success in the federal government, which means better service for our customers, the American people,” notes Beth Cobert, acting director of the Office of Personnel Management.33 After attracting and hiring top-notch people, agencies should provide an environment that supports their ability—and choice—to contribute. Yet federal scores for employee engagement consistently lag commercial counterparts, and fewer than half of government employees feel they have sufficient resources to do their jobs.34

Understanding when and where employees experience peaks and valleys in their daily work—just as marketers track customers’ pre-purchase and post-purchase behavior—offers insight into ways to clarify priorities, improve personal performance in those areas, and remove unrelated distractions.

Clarify priorities and focus

“A lot of people today are just getting told to do stuff. [We have] a very task-driven culture that produces noise around meetings, calendars, emails, and status reports, rather than saying, ‘Here’s what we are trying to achieve, any ideas on how to contribute and add value?’” observes Kris Duggan, founder of Betterworks—a startup focused on enterprise goal-setting.35 The application allows employees to set and share goals openly—on a platform where the whole organization can see what each person is working on, understand how it supports key results, and comment. This allows employees to set goals in a transparent fashion so that they can understand what others are doing and to see how individual goals fit within the overall goals of the organization.

The sales organization at the United States Postal Service (USPS) made a similar effort to connect employee contributions and business impact through peer recognition of employees who created “moments that matter” for customers. The organization identified critical moments and associated behaviors, and then set up a simple online platform to recognize when others demonstrated these behaviors—and saw overall employee engagement rise by 8 percent in the initial pilot group.36 Echo Logistics launched a similar recognition platform, and even created a badge tied directly to high-satisfaction responses from its customer relationship management system. Based on these badges, leaders then talked with these employees about their work routine—or journey—to identify and scale insights about critical moments, behaviors, and strategies to improve work across the company.37

Offer insight into work habits

In some cases, employees may understand the objective at hand, but feel they have little insight into or control of their environment as they work to achieve it. Agencies could help identify where there may be potential to achieve greater productivity using workforce-focused data analysis software, such as Genome or PRISM, to look for patterns among disparate data points—from when people come to work and leave to time spent on the phone or online.38 Empowered by these insights, employees can make individual adjustments, even for purposes of personal well-being or other “nonwork” factors that correlate with engagement.39 French gaming company Ubisoft, for example, recently offered its employees the opportunity to monitor their own stress, and saw stress levels drop 50 percent during the pilot program just by increasing awareness.40 Where a corporate program may have been difficult to design, individuals were able to make personal changes and see what works— just as online advertisers increasingly push “recommended for you” product suggestions rather than simply providing a magazine-style encyclopedia of options.

Simplify work and free up time

Many employees cite data management as their most time-consuming task—with up to 70 percent reporting that they have to enter the same data into multiple systems to do their jobs.41 Agencies may consider how to reduce administrative tasks and better enable employees to contribute to critical work. This can help address a rising feeling among employees across sectors who feel overwhelmed at work, with limited support to navigate information overload exacerbated by an “always-on” culture.42

Actions as simple as establishing a single employee interface may save employees from wasting valuable time logging into and toggling between different systems. Doing this, in fact, helped one Australian news company cut staff training time in half and reduced the number of agents’ clicks from 160 to only 11.43And looking ahead, creative bots—software applications that run automated tasks—offer the potential to further simplify employees’ experience and cut through the noise. For example, X.ai—a startup whose bot automates scheduling for meetings—is already showing how machine intelligence can radically reduce the amount of daily administrative work. Emerging technology like the Internet of Things (IoT) even offers the potential to supplant humans as the primary means of collecting, processing, and interpreting information—helping to not only eliminate tasks, but also enhance worker capabilities and insights and engage a broader ecosystem to take action.44 These shifts break many of the constraints that have traditionally defined how work is done—and make redesigning work a priority for organizations.

The decision to improve

A commitment to personal development helps further accelerate employees’ impact—but close to half of federal employees are not satisfied with the training they receive,45 and only 34 percent of organizations across sectors reward frontline leaders who encourage workers to take advantage of development opportunities.46 Helping employees learn and improve will become even more critical in the future, as emerging skills are expected to have an average shelf life of just five years.47 Learning programs that rely on a heavy planning cycle and time-intensive certifications will likely be slower to respond to major shifts, and organizations and learners may have a smaller window in which to apply new skills—or worse, may find these skills are no longer applicable.

Agencies should consider a more “agile” approach to developing people, empowering employees to customize learning to address performance gaps, career interests, or organizational needs. Understanding, segmenting, and designing for this range of needs shape a learning process that drives employees’ decision to address these needs—one built around minimally viable initial training, individualized improvement, and platforms for ongoing learning.

Design “minimum viable” training

Consumer products have recently begun to favor an “experiment and iterate” approach, launching a basic offering and then seeing what features users actually need and want. Learning programs may have a similar opportunity to more quickly deliver a core offering and supplement based on learner needs. This “minimum viable training” designs learning to tackle the basics that someone needs to survive in a new role, such as knowing the “language” of the field—and relegates the rest to “on the job” learning or apprenticeship.

The UK Government’s Department for Work and Pensions (DWP), for example, recently designed a digital academy to help employees prepare for the kinds of digital roles in high demand today. Employees spend six weeks on key technical elements in a boot camp-style curriculum, and then are assigned to a team to work on actual projects. “What you get in six or eight weeks is not going to get you to where you can drop in and lead on some of these programs, where we’re trying to deliver complex, world-class solutions in a very short space of time,” says Rick Stock, the academy’s former program director.48 Instead, the training focuses on delivering two core things—knowledge gain for the employee, and the minimum orientation to contribute to the business on “day one”—and builds on this foundation through apprenticeship.

Pinpoint individualized improvement areas

Twice-a-year evaluations offer little guidance on daily job performance, much less areas for improvement. More incisive, task-based data may assist individuals in understanding their personal mastery of concepts and skill gaps, and could also inform an organization where learning capabilities may need to be improved or where skill gaps in the workforce exist.

For example, UPS helps its employees by using sensors to monitor how delivery drivers stack packages to identify the most efficient approach, or to provide feedback to individual drivers on how often they engage in risky driving behaviors, such as backing up or turning left.49 Where feedback today is often limited to infrequent formal reviews, the information generated by workplace devices can help employees recognize where they may need to improve in real time. And since most performance gaps ultimately reflect learning gaps, emerging technologies like augmented reality can offer feedback even earlier. NASA’s “Sidekick” project, for example, uses an augmented reality device to guide astronauts through complex repair tasks they might have only one chance to get right.50

Build platforms for ongoing learning

The on-demand nature of micro-learning can empower employees to create learning solutions tailored to their performance gaps—and they will likely look to the learning function to create the forum (more than the content) to access actionable resources and a community that helps to process those resources in their context. These platforms tap into open-source content—including massive open online courses (MOOCs)—delivered in small, specific bursts over time, such as short “how to” videos lasting less than five minutes or text message-based instruction. And for unique, agency-specific information, peer learning has the potential to use collective intelligence to supplant heavy management of institutional knowledge.

Yet, offering learners a broader base of content asks that leaders think critically about how to segment employees and effectively connect them to that content. To do so, they must understand employees’ performance, preferences, environment, and technological aptitude—the work, worker, and workplace—to elucidate how different groups of employees access learning.

The US Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), for example, recently adopted new technology to support investigators—and needed to transition a workforce of 11,000 to the platform. The headache of driving compliance for a standard training course—not to mention the mission implications of sub-par adoption—prompted leaders to instead focus on what would motivate an employee to learn the new system. Through “voice of the learner” interviews, ICE developed several personas for investigators, and used these insights to design job support. The mobile, around-the-clock nature of the work, for example, prompted ICE to offer instruction in short, online video clips, while the cultural preference to “figure it out”—unsurprising in investigators—suggested they should embed links to training from the same screen as the job task. Differences between the groups also shaped the adoption strategy, creating a range of options to engage with the content. Curious agents had the opportunity to volunteer for “beta testing” and experiment with the application before release—which then offered a peer support network for later adopters, making it easy for less-enthusiastic users to access on-the-spot support. By understanding the range of employee preferences, ICE was able to offer a range of experiences and help agents master improved tools to do their work.

The decision to transition (recommit)

More than half (55 percent) of employees are constantly on the lookout or actively exploring other job opportunities,51 and it is estimated that those entering the workforce today will change jobs every 2.4 years on average.52 Agencies might accommodate this reality by reimagining career paths and structuring transitions—both finding ways to offer employees their best “next” move within their current organization, and offering more on- and off-ramps for those who do not.

Understand what motivates employees and create options for job “sculpting”

As one hospital executive noted, “We’ve missed the mark with our nurses. What motivates a labor and delivery nurse is vastly different than what motivates an emergency room nurse or oncology nurse, but we’ve been treating them all the same. . . . We need to put people in the right roles, for sure—but we also need to give nurses specific assignments that they will find motivating.”53 Tailoring an employee’s current role—or “job sculpting”—to better fit their motivations and needs may offer the opportunity to design a career he or she loves—before looking elsewhere for it.

Opportunities to invest in a skill or passion, whether through a 15-minute project or a year at another agency, may also be re-energizing for employees. Like product strategies that bundle goods, offering employees choice and flexibility even for just a few hours a week in their current role may build commitment to the job.

Consider the “persona” of an enthusiastic federal employee excited about new ideas for making government better—just as the State Department recently did. Its Foreign Service officers—particularly junior officers—tend to be highly educated and motivated, but spend their first few years performing consular work, typically processing visas and passports. To tap into this underutilized potential, the department worked with 18F to develop Midas, an online platform that matches people to projects outside of their regular job—and which was recently recognized with the NextGen Exemplary Group Award.54

Embrace nontraditional career paths

With the idea of a monolithic career rapidly fading, an employee’s journey will probably not be entirely within a single agency. Thus, government agencies should consider how to manage career paths that include moves outside of the organization. LinkedIn founder Reid Hoffman describes this idea as “tours of duty,” drawing on the military origins of the term to describe how workers and employers agree to “honorably accomplish a specific, finite mission.”55

With higher turnover, agencies should consider what differentiated value they offer to employees who complete a tour at their agency—and even recommit or return. As Clayton Christensen points out in his seminal work on disruptive innovation, “Customers do not buy products; they hire them to meet a need”56—and the same is true for employees investing in career experiences. Why, for example, do many talented professionals covet stints in Silicon Valley? Agencies should identify an unmet career development need, and become the “go-to” source for that need. With the right positioning and differentiated brand, transitions are not a threat, and may even be an opportunity to tap into fresh ideas and new skills. As National Security Agency director Admiral Mike Rogers notes: “How do you make sure that we maintain our agility, our technical proficiency, and our expertise across a broad set of problem sets if we’re only bringing three percent of the workforce in a year? How can we bring in people from the private sector who would work with us for a year or two?”57

Agencies also should not entirely discount employees who have transitioned to jobs outside the agency. It’s not just that they may someday recommit; former employees also serve as brand ambassadors, refer talent, or offer a network of useful intelligence. In many cases, they may even continue to work within the agency’s talent ecosystem as freelance or contract employees. Creating more open platforms for learning or performance engagement may drive loyalty and continued mission contribution. In the same way that companies invest in maintaining customer relationships (CRM), agencies should invest in managing alumni relationships—just as the Gates Foundation has done. Workers who leave the foundation often go on to similar roles within the nonprofit sector, and often value a structured way to stay connected to news, training, and networking events focused on the sector—which the foundation offers to more than 1,200 alumni through its platform.58

Conclusion

Most organizations today have established processes to identify the tools or strategies to win in an evolving environment—but seldom apply the same precision to harnessing the talent they need to deploy these strategies. To be able to generate great ideas and translate them into action, government requires employees who care deeply about achieving the goals of their organization—and make the decision to join, contribute, improve, and recommit. If they are neither enabled nor supported by their organization, or if they feel leadership is oblivious to their—and customers’—needs, employee engagement can deteriorate.59

In this sense, the future of work—and effective public service—is about strengthening the employee experience. Doing so will likely involve several key shifts: framing employees’ experience in the context of the work, as Transport for London and USPS did; identifying how employees’ preferences and motivations shape their experience, like FLRA and ICE; and empowering managers and employees to co-create solutions, like the US State Department and DWP. Moreover, few of the organizations in these examples focused solely on the HR function; most featured mission executives trying new management strategies as part of how they do work—from designing recruiting games for a specific workforce segment, to planting ads in code, to reskilling agents on how to use new investigation software. Frontline managers are central to design-driven talent solutions; they typically have the most to gain from better performance, and best understand how to shape employees’ decisions to deliver it.

“Coupling user experience and design thinking has already helped many in the federal community realize the vast strategic potential to recruit and develop a stronger and more customer-focused future federal workforce,”60 notes Dr. Bill Brantley, a career civil servant and adjunct public administration professor who specializes in federal human resources. The early examples featured in this study illustrate how applying these tools to specific challenges can radically reframe today’s approach to managing workers. However, each illustrates the tool or approach, and is not itself the answer. Government executives should consider how these tools can help their agencies experiment and find new ways to improve the employee experience within their context—and they should start today.

Deloitte Consulting LLP’s Talent Strategies practice assists organizations with the activities, processes, and infrastructure to drive employee performance, engagement, and retention. Read more about our Talent Strategies offerings on http://www.deloitte.com/global/en/pages/human-capital/solutions/talent-strategies.html.