The consumer is changing, but perhaps not how you think A swirl of economic and marketplace dynamics is influencing consumer behavior

26 minute read

29 May 2019

Contrary to conventional wisdom, there's been no fundamental rewiring of the consumer. The modern consumer is a construct of growing economic pressure and increasing competitive options.

The consumer is changing. They are more capricious and less loyal. They have less time but are more conscientious. They shy away from stores and prefer experiences over products. Today’s consumer is an entirely different animal—and unrecognizable from their peer from the good old days. This brand of conventional wisdoms has been proliferating in the marketplace for a few years now. It appears as if there has been a seismic shift in the consumer’s mindset—and choices—a shift that has left the market asking: “Who is this brand-new consumer?”

Learn more

Explore more articles from Retail and consumer products

Subscribe to receive related content on Consumer business

In a hurry? Read a brief version from Deloitte Review, issue 25

Download the issue

Download the Deloitte Insights and Dow Jones app

There are even more clichés surrounding the millennial consumer. They are often branded as being more narcissistic, more idealistic, more socially-conscious, and more experience-oriented than any of their preceding generations. They have even been blamed for ruining everything from movies to marriage!1 They seem to have broken the mold of their similar-aged cohorts of past eras.

Amid this confusing and fast-changing narrative about the changing consumer, we paused to ask ourselves some hard-hitting questions to cut through the noise and arrive at the truth. Has the consumer fundamentally changed? If yes, in what ways have they changed? Is there a seismic difference in the changes that we are witnessing? More importantly, is the hysteria in the marketplace obscuring a much deeper and more fundamental change in consumer behavior?

It is with these questions in mind that we conducted a year-long study to go beyond the headlines and unearth more profound observations about the consumer that might have been either missed or misunderstood in the midst of the hype.

Our findings debunked many conventional wisdoms about the new-age consumer. What we learned is that the consumer hasn't fundamentally changed, but to the extent they are changing is because the environment around them is evolving, characterized by economic constraints and new competitive options. They’re changing because of the financial constraints they find themselves in. This, in turn, has been triggered by a rise in nondiscretionary expenses such as health care and education and the growing bifurcation between income groups. They’re also changing in reaction to the abundance of competitive options available to them, made possible by technology.

It’s this swirl of financial and marketplace dynamics that is heavily influencing the behavior of today’s consumer as opposed to a fundamental rewiring.

Understanding the consumer: Our approach

We undertook a yearlong journey to study the consumer. We scoured government data; talked to clients, industry leaders, and analysts; conducted primary interviews; and surveyed a representative sample of more than 4,000 consumers from the United States. Working with Deloitte’s Center for Consumer Insights, we conducted primary research, leveraging 450 billion unique points of location data and more than 200 billion points of credit card transactions. Our goal was to examine the current state of the consumer as well as to study their behavior and underlying attributes to see if there were nuances and intricacies that were being missed.

We adopted a two-pronged approach to our research.

First, we zoomed out to study the macro demographic, cultural, and economic trends related to the US consumer. Our focus here was not on behavior but on broad trends that impact behavior. It’s similar to the approach we took in an earlier study, The great retail bifurcation.2 In that, we looked at the income and expenditure data to examine whether and how the economic situation of consumers had changed and the implications of that change. But this time, we wanted to go deeper: We wanted to dig into other broad categories of demographics and regional changes to see where they live, their ethnicity and race, and how factors such as economic situation and health status are driving changes in consumer behavior.

Second, we examined primary data on the consumer’s changing demographics and economics to understand consumer behavior—not just their overall behavior but their micro-behaviors, which differ, sometimes substantially, within emerging segments. We looked deeply at how they spend their money and time, where they go, and what’s most important to them.

In this report, we have highlighted the most intriguing insights from our study to put together the construct of a consumer who in some ways is changing and in other ways isn’t really changing at all.

The changing consumer: Deconstructing demographic dynamics

A grasp of demographics is critical to understand what makes the world—and the consumer—tick. We are our demographics. This doesn’t mean that the consumer can be reduced to the sum of their individual demographic categories. It means that they’re a creation of the complex interplay of ever-shifting demographic forces that create unique needs, cultural biases, and define consumer behaviors.

To understand how, where, and why the consumer is changing, one must understand their underlying demographics, which include much more than just life span, fertility rate, race, and ethnicity. Health, culture, economics, and education are all critical dimensions of demographics—as are geography, regionalism, and the urban-suburban-rural divide. Understanding these changing demographics helps shine the light on any emerging pockets of opportunity.

Millennials are the most diverse generational cohort in US history.

A diversifying consumer base with diverse needs

There is a seismic shift that has taken place in the United States over the past 50 years. The population has become increasingly heterogeneous: Millennials, now representing 30 percent of the population, are the most diverse generational cohort in US history, with roughly 44 percent consisting of ethnic and racial minorities. In comparison, only 25 percent of baby boomers belong to ethnic and racial minorities (figure 1).3

This increased diversity, while most pronounced in the millennial generation, is not a uniquely millennial attribute. The shift in the ethnic and racial makeup of the United States has been underway for some time now, with the consumer base becoming increasingly diverse. The current racial makeup of the United States (and the consumer) is barely 50 percent white and the number is likely to continue shrinking.4 The non-Hispanic white population is projected to drop from 199 million in 2020 to 179 million in 2060—a decline of 10 percent—even as the US population continues to grow.5

This shows that we have moved to a diverse, splintered, and heterogeneous consumer base with a much broader and varied set of demands and needs. Moreover, the upcoming Gen Z cohort is likely to bring further diversification of the consumer base along racial and ethnic lines.

Young consumers are moving toward city centers

The old axiom of politics, “All politics is local,” is also applicable to consumer trends. Where the consumer lives—or their geography—further shapes their needs and demands.

For much of the late 19th and early 20th century, Americans settled in cities in pursuit of factory work. Following World War II, families fled cities to suburbs that epitomized the American Dream—a few kids, a dog, and a house with a white picket fence that the working-class American could suddenly afford.6 This demographic transformation radically changed the retail landscape and the consumer.

The United States has moved to a more diverse, heterogeneous consumer, with a much broader set of needs.

Looking at geographic data from 2000–2014, we see that the trend of movement to the suburbs is still intact. Suburban life appears to be flourishing, with suburbs witnessing a net population growth and cities and rural areas seeing a decline.7

However, within this geographic data, gradations are beginning to appear, bringing with them further splintering of the marketplace. Rather than leaving urban centers (which was characteristic of the baby boomers), young consumers appear to have reversed course and are moving closer to the urban core—to city centers—possibly drawn by proximity to work and cultural activities.

Now, to a degree, one can argue that this trend is part of the general pattern—that when the younger consumers finally do settle down and start families, they will follow in the footsteps of their predecessors and move to the suburbs. However, the data shows a significant jump in the population growth rate of younger consumers in and around cities in the decade beginning 2010 (18 percent), as opposed to the declining growth rate in the previous decade—2000–2009 (–4 percent).8

This reverse trend of movement toward city centers is adding to the complexity of the consumer landscape, just as the postwar migration to the suburbs significantly impacted power and the distribution of money in the mid-20th century. It’s critical to monitor these migratory patterns as they influence the consumer’s decision-making and purchasing behavior across a broad set of categories, from rent to personal care products.9

Regional migration is fragmenting the consumer base

Geography isn’t simply urban vs. rural. There are also broader regional population trends at play—the movement of people within the United States—which shape geographic markets. As the census population estimates show, the migration of people from the Northeast and Midwest to the Southeast and to the West continues to be a trend.10

However, once you dive beneath the surface and examine the internal migration trends through the lens of age, stark differences begin to emerge. Baby boomers (many now in retirement mode) are moving to Florida and Arizona, which claimed eight of their top 10 metro destinations; Gen Xers are relocating to Texas, where five of their top 10 metro destinations lie; and millennials are migrating to Colorado and Florida, which contain five of their top 10 metro destinations.11

This trend is fragmenting the consumer base further, as each age cohort follows a different debarkation and migration pattern. It also means that each generational cohort brings its own set of needs and demands to the region they migrate to, further amplifying the differences among consumers in various parts of the country. If you take these different lenses—race and ethnicity, urban vs. rural, and geography—in conjunction, it is increasingly evident that the consumer can’t be thought of in simple, generalized ways. Instead, we need to look at them through a kaleidoscope of factors to create a more complete picture of the dynamic consumer.

The consumer is more educated, and is spending differently

We looked at other shifts as well—for instance, cultural influences—to understand ways in which the consumer has changed. Over the past 20 years, the percentage of the population with college degrees or higher has increased significantly, though not uniformly—white and black Americans with a college education have increased by 12 percent and Hispanics by 7 percent.12

As a result, we’re moving toward a more educated and knowledgeable consumer base with different spending patterns. However, the cost of education eats into discretionary funds, influencing how consumers spend their money on categories such as apparel, food away from home, and furniture. 13

People are buying homes and getting married later—or never

Demographics, migration patterns, and education levels are not the only factors evolving. Homeownership is a key life cycle milestone that also impacts consumer behavior. There has been a marked drop in the percentage of consumers choosing to own homes and many of them are waiting longer to buy homes. Between 2007 and 2017, the percentage of homeownership fell from 68 percent to 64 percent.14 One possible consequence of tougher lending standards could be the rise in the median age of first-time buyers to 32 years (from 31 at the start of the period), an increase of 3 percent.15 Digging deeper into the median income figures of homeowners, we found that the percentage of owners with above-median income slipped to 78 percent in 2017 from 83 percent in 2007, which suggests that homeownership is no longer an essential part of the American Dream.

Marriage, another life cycle milestone, continues to evolve. Between 1997 and 2017, marital rates among whites, Hispanics, and blacks fell from 59 percent, 54 percent, and 39 percent to 55 percent, 50 percent, and 35 percent respectively.16 The only exception to this downward trend were Asians, whose marriage rate increased from 58 percent in 1997 to 61 percent in 2017; the trend has been relatively steady since then.

Between 2007 and 2017, income growth for the high-income cohort rose 1,305 percent more than the lower-income group in the United States.

Not only are fewer people marrying, they’re also delaying marriage: In a single generation, the median age of first marriage has risen from 26 to 28.5 years.17 The effect of this delay ripples through various other life cycle milestones, such as an increase in the average age of women having their first children—up from 21 years in 1972 to 26 years in 2016.18

These changes in key life cycle milestones potentially influence how consumers spend their money at retailers across categories as spending takes place at later stages.

The economic divide is deepening

In any discourse on the consumer, it would be remiss not to mention their changing economic situation. As we first highlighted in The great retail bifurcation,19 there is a deepening economic bifurcation between the top 20 percent income earners and the rest of the population—a divide that has a huge impact on consumer behavior.

Between 2007 and 2017, income growth for the high-income cohort (>US$100,000 in mean household income) rose 1,305 percent more than the lower-income group (<US$50,000 in mean household income) in the United States. This divide has been even more conspicuous because of the rise in nondiscretionary expenses across groups (figure 2). The bottom 40 percent of earners had less discretionary income in 2017 than they did 10 years ago, and the next 40 percent saw only a minor increase. Only 20 percent of consumers were meaningfully better off in 2017 than they were in 2007, with precious little income left to spend on discretionary retail.

To make matters even more complex for retailers, new expenses and needs have arisen over the past decade that compete with traditional retail categories. These demands—such as for mobile phone and data plans—were minimal 10 years ago. So, traditional retailers have new competition for consumers’ discretionary dollars.

This income gap has introduced sharp distinctions between income categories as outlined in The great retail bifurcation and the growing chasm is having a significant impact on the consumer landscape.20

Life expectancy is on the rise, but so is obesity

On the positive side, life expectancy rates have risen by 2.5 years on average, which means people are living longer lives—but not necessarily healthier ones.21 The percentage of people who are overweight or obese soared from 22 percent in 1994 to 42 percent in 2016, nearly doubling.

So, there is a divide in obesity rates as well, with significantly lower obesity rates among high-income consumers as compared to the low- and middle-income groups. Interestingly, even the high-income cohort saw the obesity rate rise between 2007 and 2017, though more modestly than other income cohorts.

Inevitably, obesity impacts where consumers spend their money. An individual with a body mass index (BMI) that’s considered “obese” spends 42 percent more on direct health care costs than adults who are a healthy weight.22 These health care costs eat away at funds that may otherwise have been used on discretionary expenditure.

Are millennials losing economically?

The millennial has often been portrayed as a consumer who is at the epicenter of the disruption that’s taken place in every aspect of society, from marriage to childbearing to homeownership.23

Certainly, there are generational differences between this group and past cohorts: Millennials are better educated and are marrying later, buying homes later, and having children later than the boomers did. But this trend is part of a broader one that’s been underway for decades.

Further, blaming these changes in life cycle milestones squarely on millennials ignores some non-age-related trends that are clear in the data. Applying the lens of diversity on life cycle milestones reveals differences between racial and ethnic groups. For example, among Asian millennials, first marriages are happening within a narrow age band. In contrast, the distribution is much broader among white, black, and Hispanic millennials.

Millennials are dramatically financially worse off than previous cohorts with a 34 percent decrease in their net worth since 1996.

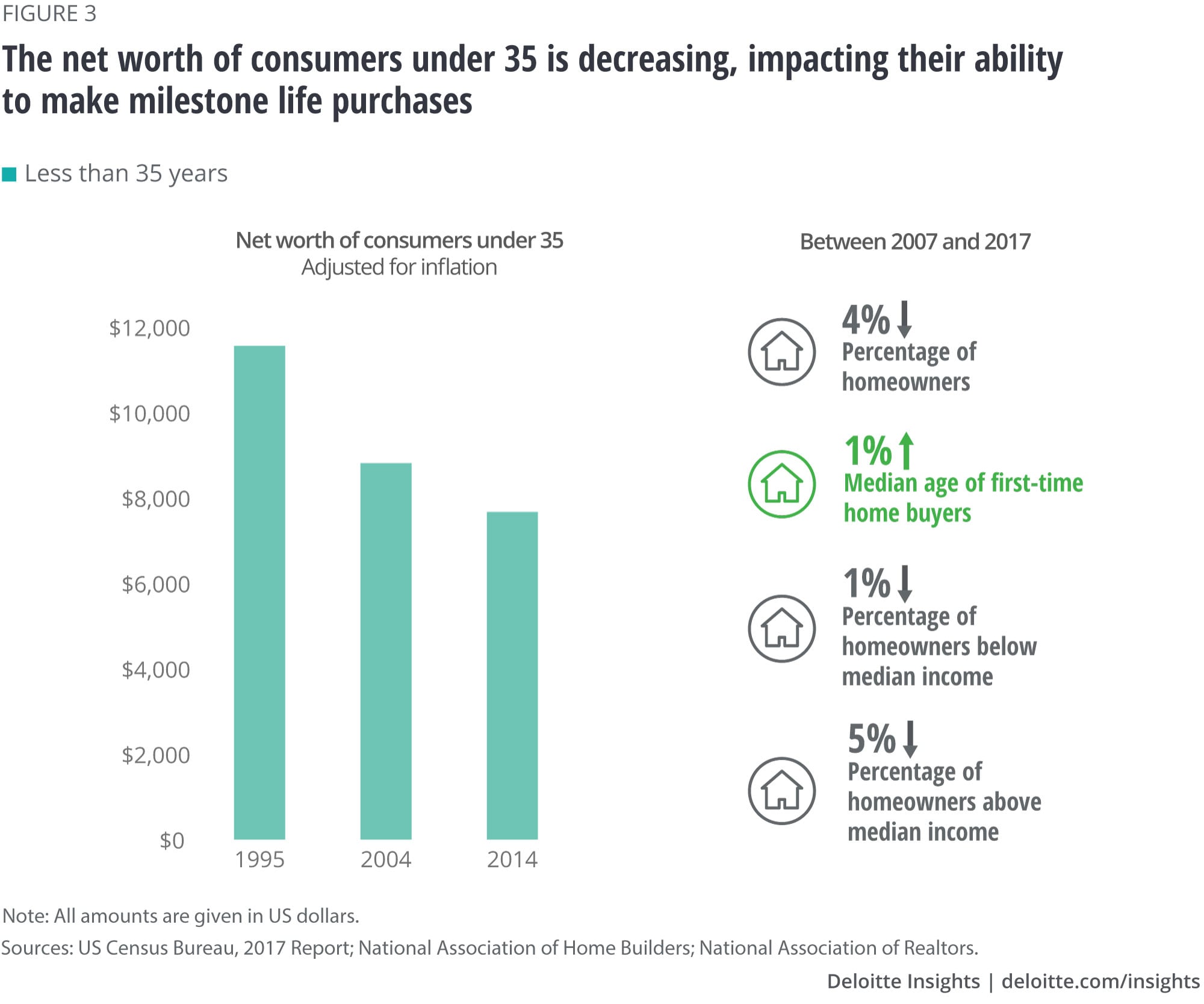

Moreover, there’s a good reason why millennials are reaching these milestones later in life: they are significantly financially worse off than previous similar-aged cohorts. Since 1996, the net worth of consumers under the age of 35 has fallen by 34 percent.24 Homeownership for the cohort declined by more than 4 percent between 2007 and 2017 (figure 3). And the rise in the education level of millennials hasn’t come cheap: Between 2004 and 2017, student debt has increased for consumers under 30 by 160 percent. Typecasting the millennial as simply being “different” overlooks a much bigger factor—that of their economic constraints.

Companies often say they need to “win with the millennial.” But the data about the economic well-being of this cohort shows that the millennial may well be losing economically.

To conclude, today’s consumer—both millennial and nonmillennial—is not an entirely different species. However, they’re operating in a new demographic, economic, and cultural landscape as described below:

- The consumer base is increasingly diverse. The current consumer base has evolved in the cross-currents of a set of broader demographic trends that have turned what was a homogeneous mass market into a heterogeneous marketplace, consisting of multiple competitive options to choose from.

- Economically, the modern consumer is under greater financial pressures compared to the consumer of 30 years ago. This is particularly evident among low-income, middle-income, and millennial consumers.

- Consumers are delaying key life cycle milestones. From marriage and homeownership to having children, these delayed milestones (especially among millennials) have implications on consumer behavior.

These demographic, economic, and cultural forces have created a marketplace that is fragmented. And the average consumer base is representative of increasingly diverse subsets of consumers with distinct needs who have increasingly distinct competitive options to address those needs.

Beyond demographics: A deep dive into consumer behavior

Demographics by themselves do not tell the entire story. So, we looked deeply at consumer behaviors. Specifically, we looked for changes or insights across four broad behavioral aspects of the consumer: How they spend money, how they occupy their time, where they go, and what matters to them.

In our analysis, we applied demographic and geographical lenses to see if there are, in fact, changes in modern consumer behavior as compared to the past, and how these changes measure up to marketplace axioms.

How are consumers spending their money?

Since 2005, total retail spending in the United States has risen by about 13 percent to around US$3 trillion annually. The retail market has been growing and continues to expand. In fact, in 2017, retail grew a healthy 2.3 percent.25 However, per capita retail spending remained flat for the most part of the period, meaning that population growth, rather than greater spending per person, was the primary driver of the increase in spending.26

Also, surprisingly, the share of wallet data over a 20-year period reveals relatively consistent spending across most consumer categories. Food, alcohol, furniture, food away from home, and housing all constitute roughly the same percentage of the consumer’s wallet today as they did in 1997. Even entertainment, a category where one might expect to see an increase in experience-driven spending, was basically flat. In fact, for consumers under 30, spend on entertainment declined from 5 percent to 4 percent of the total wallet.27

The notable exception to stable consumer categories is apparel, where spending as a percentage of the total wallet has been cut in half since 1987, declining from 5 percent to 2 percent (figure 4).28 However, this sharp drop does not necessarily imply a disinterest in clothing or fashion on the part of the consumer.

Population growth has been the primary driver of retail growth.

In fact, there has been a continued increase in the number of units of apparel sold, consistent with the overall rate of growth in retail.29 Further, apparel spending by age cohort shows a similar phenomenon, with a similar decline in share of wallet in the category irrespective of age cohort. The data reveals a deeper story of deflationary pressures on apparel unit prices, with a significant downward trend in revenue per unit.30 It shows that the consumer is still buying apparel at relatively robust levels. This trend is largely driven by changes in the competitive market, with market forces driving down the price per unit.

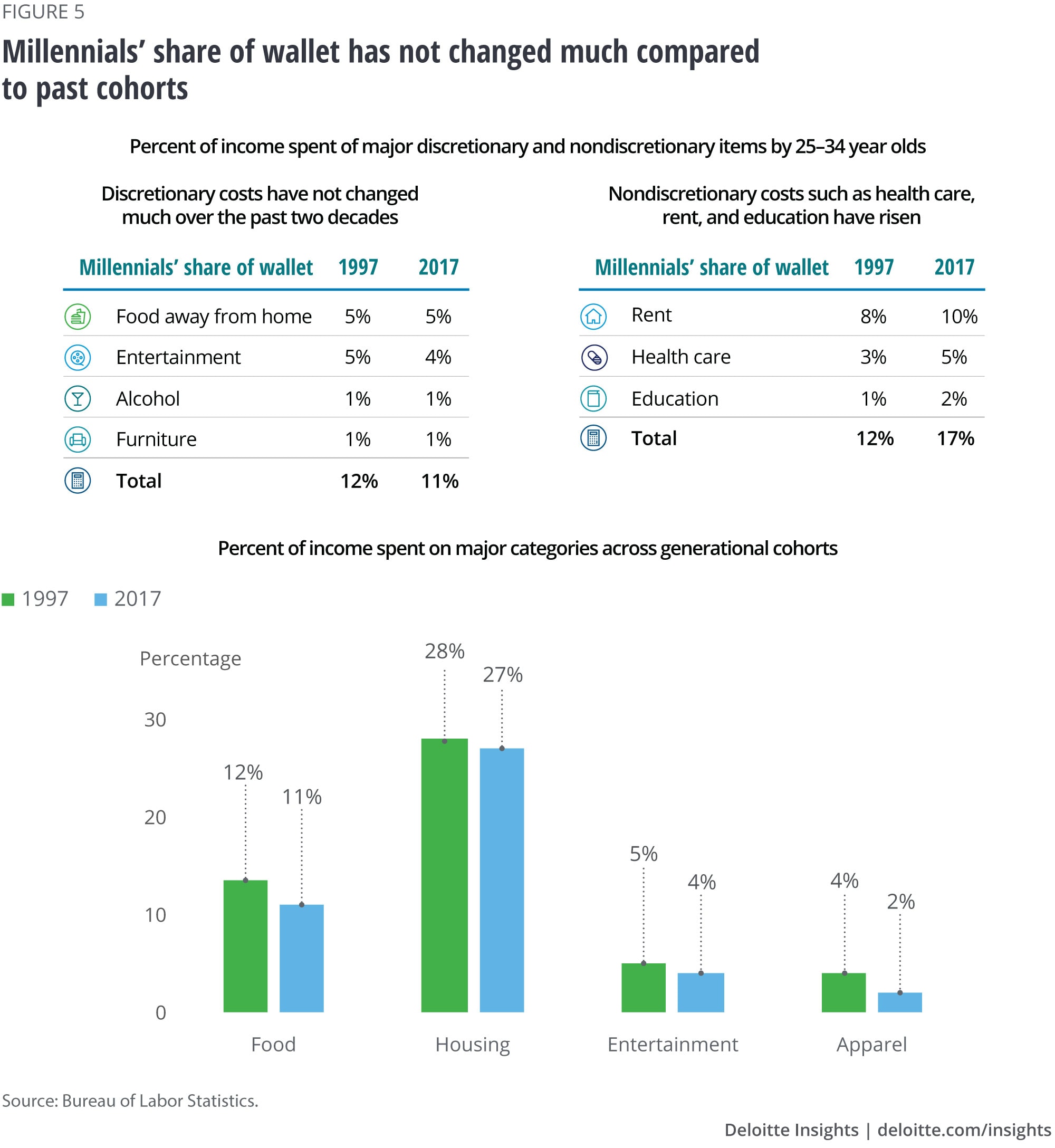

But what about millennials? Is there a material difference in their spending habits as compared to those of similarly aged cohorts in the past? After all, the common perception is that they’re the ones driving significant disruption. An analysis of spending patterns of similarly aged consumers over a 30-year period reveals few significant shifts in spending allocation, with changes confined to a tight 1 percent to 2 percent range (figure 5). Interestingly, the real differences show up in several nondiscretionary expenditure categories. A growing share of the millennial’s wallet is going toward health care expenses, housing costs, and education, highlighting not so much a change in the consumer, but rather a change in the economic pressures that the young consumer is under.

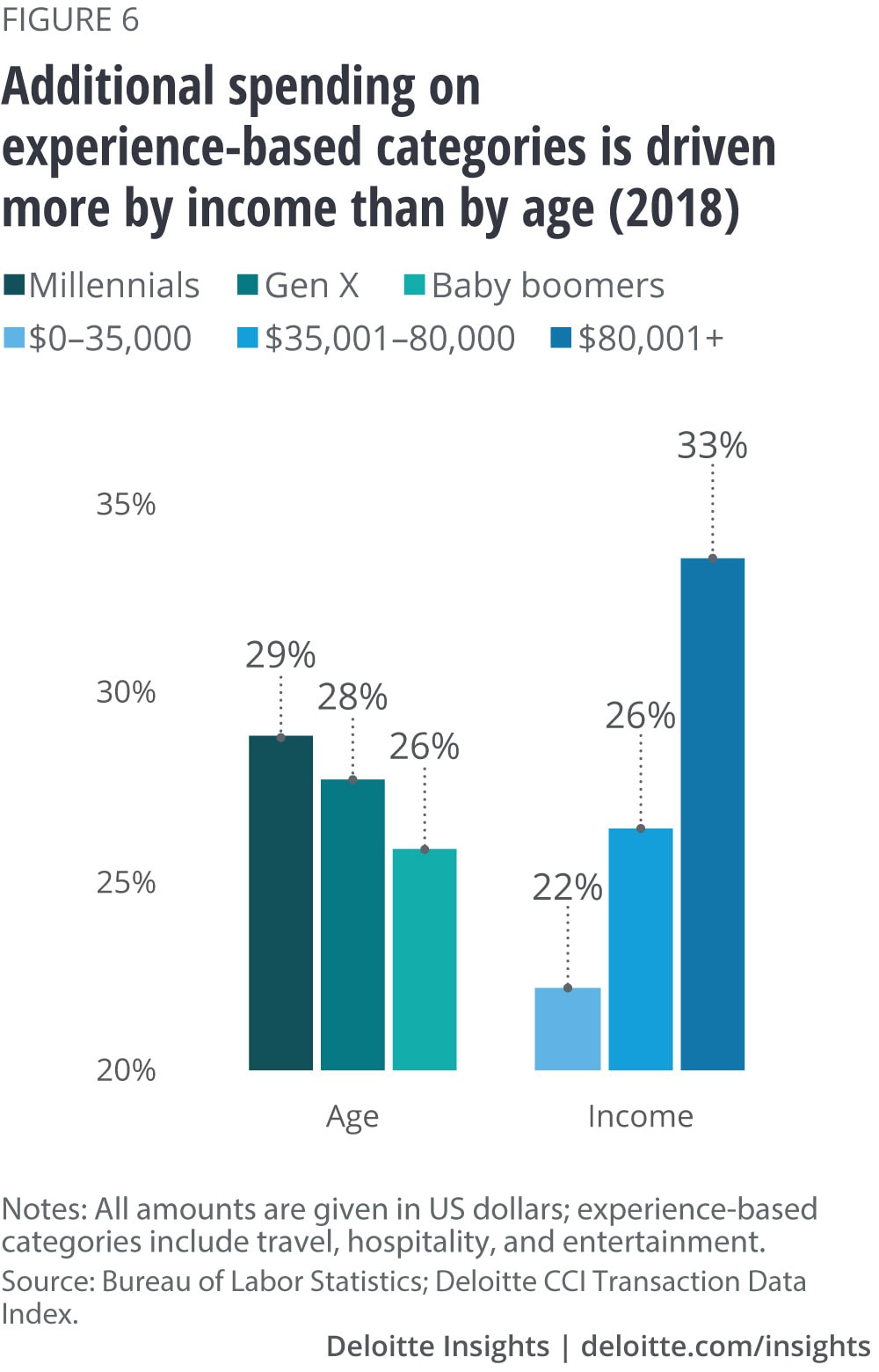

This observation runs counter to conventional wisdom, which posits that millennials have shifted spending categories toward experiences and away from products. There is a nugget of truth in the popular idea, though. High-income millennials are spending almost a third of their discretionary income on entertainment, and as their income levels rise, the absolute dollars spent on entertainment rise.

Seeing this split in millennial consumer behavior along the lines of income, we dug further to see if the same pattern was prevalent among other age cohorts. Indeed, increased spending on entertainment is strongly correlated to income group, much stronger than any age-related difference (figure 6). It’s not the younger consumer who’s shifting toward entertainment-based spending, but rather the higher-income consumer with growing discretionary spend.

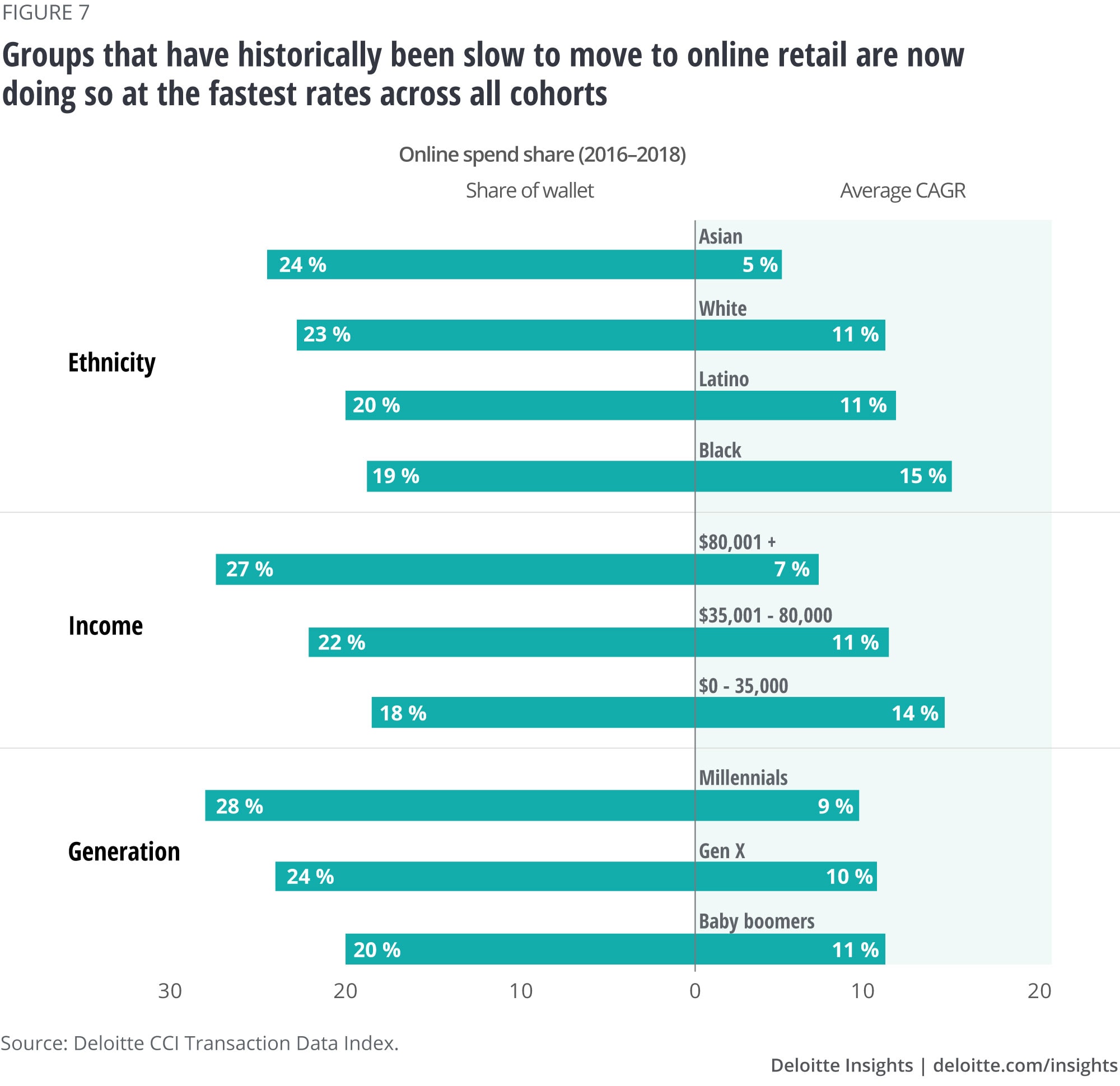

In addition to assessing spend by income and age, we challenged the existing notion around—who is the consumer using e-commerce. E-commerce, which currently stands at US$517.4 billion—climbing 15 percent in 201831—has grown sharply over the past decade.32 What is more interesting is how the consumer who shops through digital channels may be changing. Not surprisingly, higher-income groups, because they have better access to technology, spend a larger share of their wallet online than lower-income groups—27 percent versus 19 percent. The same trend is visible among millennials (28 percent) versus boomers (20 percent).

It’s not age but income that is driving the share of wallet allocation toward entertainment.

However, low-income, black, and Hispanic groups are among the fast-growing populations in terms of online purchasing (CAGRs of 14.3 percent, 14.7 percent, and 11.5 percent respectively), revealing a quickly expanding pocket of opportunity for e-commerce (figure 7).33

This growing opportunity prompted us to do a competitive review of Walmart and Amazon to see which one of these US retail behemoths is winning with these fast-growing, under-penetrated online consumer cohorts. It appears that Walmart is popular among the baby boomers and the lower-income group, as it is growing its digital sales for these cohorts at 1.4 times and 1.2 times the rate of Amazon, respectively. Since its acquisition of e-commerce retailer Jet.com, Walmart has posted a 44 percent increase in e-commerce sales, driven heavily by its current consumer base’s increased online spending.34

As far as spending patterns are concerned, today’s consumer is not so different from yesterday’s buyer. US retail spending has grown, but this trend has been in line with the population growth even as per capita spending remains flat. We’ve also seen that within specific categories—such as food, housing, and entertainment—the change in share of wallet stayed within a tight range. That’s not to say that there have been no shifts whatsoever, but some of them—such as the declining share of wallet represented by apparel—reflect broader competitive changes in the market and deflationary forces.

Where real changes show up are in the spending patterns of different income groups—shifts that reflect the growing income bifurcation in the United States. These spending categories appear to be having an impact on millennials, who are delaying life cycle milestones—not necessarily due to a change in values but possibly because family, children, and homeownership are out of reach financially.

Time is money. So where are consumers spending it?

It seems to be a commonly accepted truism that we are living in the age of the “time-starved consumer” who has less time than ever before. But a day is still 24 hours. That hasn’t changed. So, what has?

In our survey, 76 percent of the respondents reported having less or the same amount of free time than just a year before. Our results, therefore, corroborate the broadly held view that consumers have less free time than before, at least in perception.

But here, once again, a deeper cut of the data tells a different story. While it is a fact that the total hours worked in the United States has risen by 43 percent since 1980, the increase has been driven by the growth of the workforce. When we factor in the increased working-age population and labor force participation over the years, the average hours worked per person has fallen by 9 percent since 1960, which means people are spending less time working.35

According to the Deloitte Consumer Change Study 2018, the time not spent at work is only being partially redirected toward other nondiscretionary activities, such as personal care and household-related events, which rose 13 percent and 8 percent, respectively. In fact, the amount of time spent on leisure by the average consumer has risen. Available discretionary time is up overall, with time spent on leisure and sports increasing 5 percent between 2007–2017, or an additional 14 minutes daily, despite what consumers may be feeling.

According to OECD and Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis data, there has been a 9 percent decrease in hours worked per person since 1960.

One activity to which consumers have not been devoting as much time as in the past is shopping. According to the US Census Bureau, 2017, the number of minutes spent shopping has fallen by one-fifth over the past 13 years. The average consumer is spending 20 percent fewer minutes shopping every week.36 It’s natural to assume that the decline is likely a result of growing disinterest in shopping, but this assumption fails to account for an important difference—the multitude of shopping channels available. Today, more than ever before, consumers have more efficient ways of shopping, so this decline may not actually reflect a disinterest in shopping itself.

This decline in time spent shopping is accompanied by data that shows certain cohorts—such as rural, male, and high-income consumers—are shopping at fewer places as compared to 2017.37 As a result, the minutes spent by consumers shopping have become increasingly valuable to retailers.

So, a data-backed analysis of how the consumer is spending their time shows that contrary to the popular perception of the stressed and harried consumer, the reality is that people today have more discretionary time than ever before. What appears to be happening is that the consumer is not able to relax during the increased discretionary time as having to choose between the options competing for that free time is exhausting!

Where are consumers going these days?

There’s another conventional wisdom prevalent about the consumer—that greater adoption of digital is resulting in fewer retail-oriented trips. However, an in-depth review of location and traffic data revealed that in 2018, consumers went more places and made more trips than they did the previous year, with consumer-oriented traffic (retail, convenience, and hospitality/travel) increasing by 6 percent in April–December 2017 vs. April–December 2018.

Trips to hospitality, travel, and entertainment destinations rose by 8 percent in 2018. Trips to convenience, quick service restaurants (QSR), and fuel stations jumped 16 percent. Even brick-and-mortar retail saw a 2 percent increase in traffic. The biggest gains were seen in grocery-related trips, which grew 7.7 percent in 2018, with a notable decrease in visits to traditional retail locations such as apparel stores (1.7 percent) and department stores (10.3 percent).38

But these changes don’t consistently play out across all cohorts, with the gap most apparent across income groups. For example, the data reveals that the mix of trips by high-income consumers is skewed 2.4 percent more toward hospitality, travel, and entertainment than the low-income group.

More importantly, gains and losses in shopping trips are concentrated among a fraction of the 259,000-plus stores in the United States, with 22 percent of the stores accounting for 90 percent of the gains, and 16 percent stores responsible for 90 percent of the lost trips.

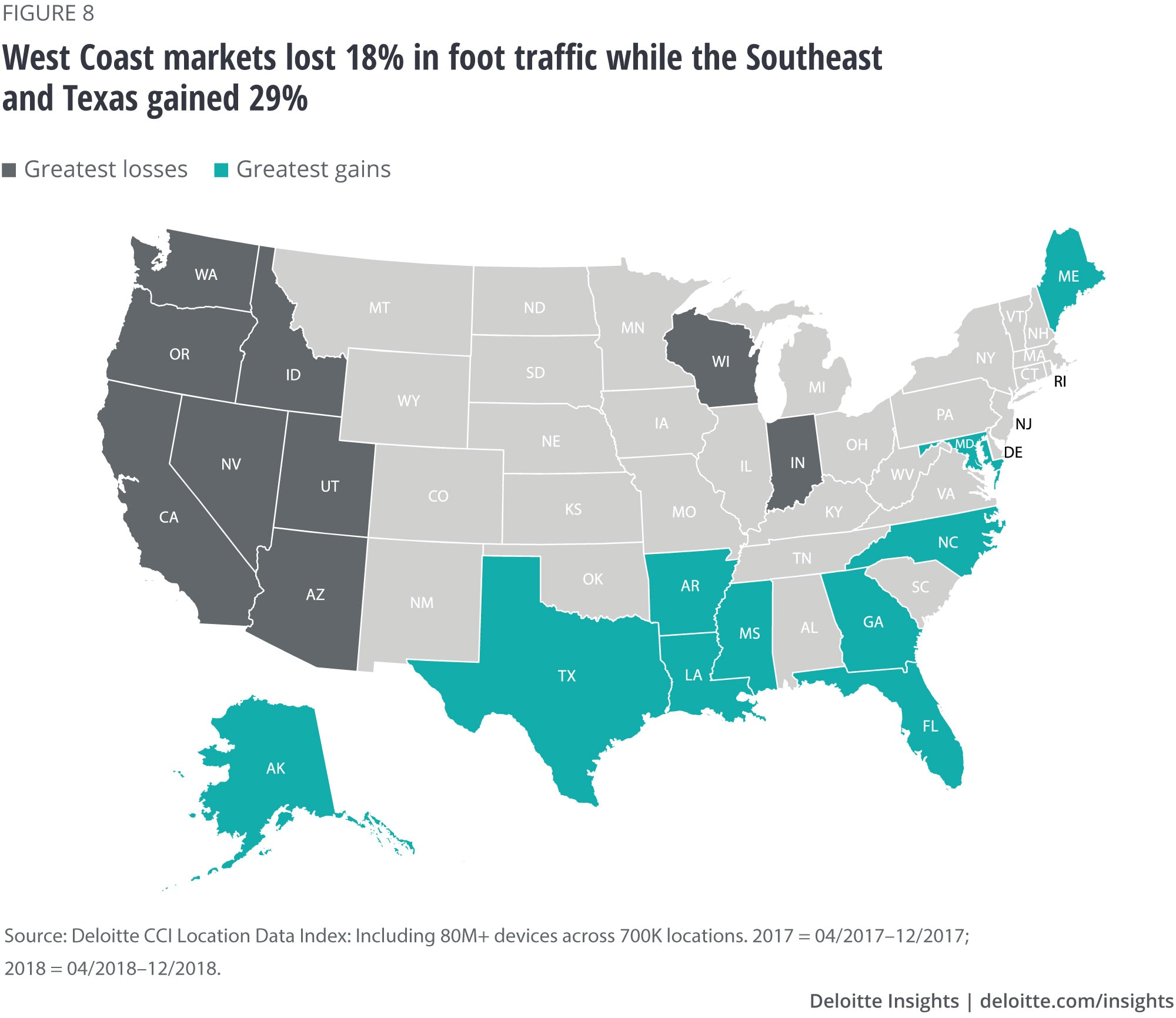

Additionally, the trends related to traffic are not homogeneous by market. The markets hit hardest by declining traffic are also highly consolidated, with the 15 fastest-declining markets largely centering around West Coast urban centers and the 15 fastest-gaining markets centered in the Southeast and Texas (figure 8). Further, and perhaps not surprisingly, e-commerce penetration in those geographies is highly correlated with a decrease in foot traffic. The West Coast Markets had an average e-commerce penetration of 25 percent while the Southeast and Texas (where foot traffic growth was strongest) had an average e-commerce penetration of 20 percent. 39

On-mall shopping is on the decline (-7.6 percent) while off-mall shopping is up (+0.5 percent). But while conventional wisdom holds that shoppers are shifting their trips away from malls, this is only half the story. What our location data revealed is that this shift away from malls is happening fastest and most dramatically among the older and higher-income cohorts—groups that have traditionally been the core shopper in malls.40

There is a myth that the new-age consumer never leaves their house: They’re glued to their devices, ordering personal digital assistants to do everything from shopping to shutting off the lights. According to this narrative, only experiential-oriented retail can get them off their sofas. While there is some truth in the notion that the consumer is going out less, it needs to be viewed through the lens of income. Then we see that the high-income cohort is going on more “fun” outings, such as hospitality, travel, and entertainment, and the lower-income group is going out less, relatively.

However, it’s important to not let the high-income cohort skew the entire story. When we investigate where consumers are going, we see they’re going more places and leaving the house more frequently—not less as assumed.

What matters to consumers?

Changing consumer values have garnered a great deal of attention in recent years. Much has been said and written about how consumers seem increasingly focused on where products are sourced from, child labor in product development, supply chain transparency, sustainability, and other ethical matters. There’s also a view that consumers are increasingly drawn to products that are personalized. But are these factors determining their decision-making process?

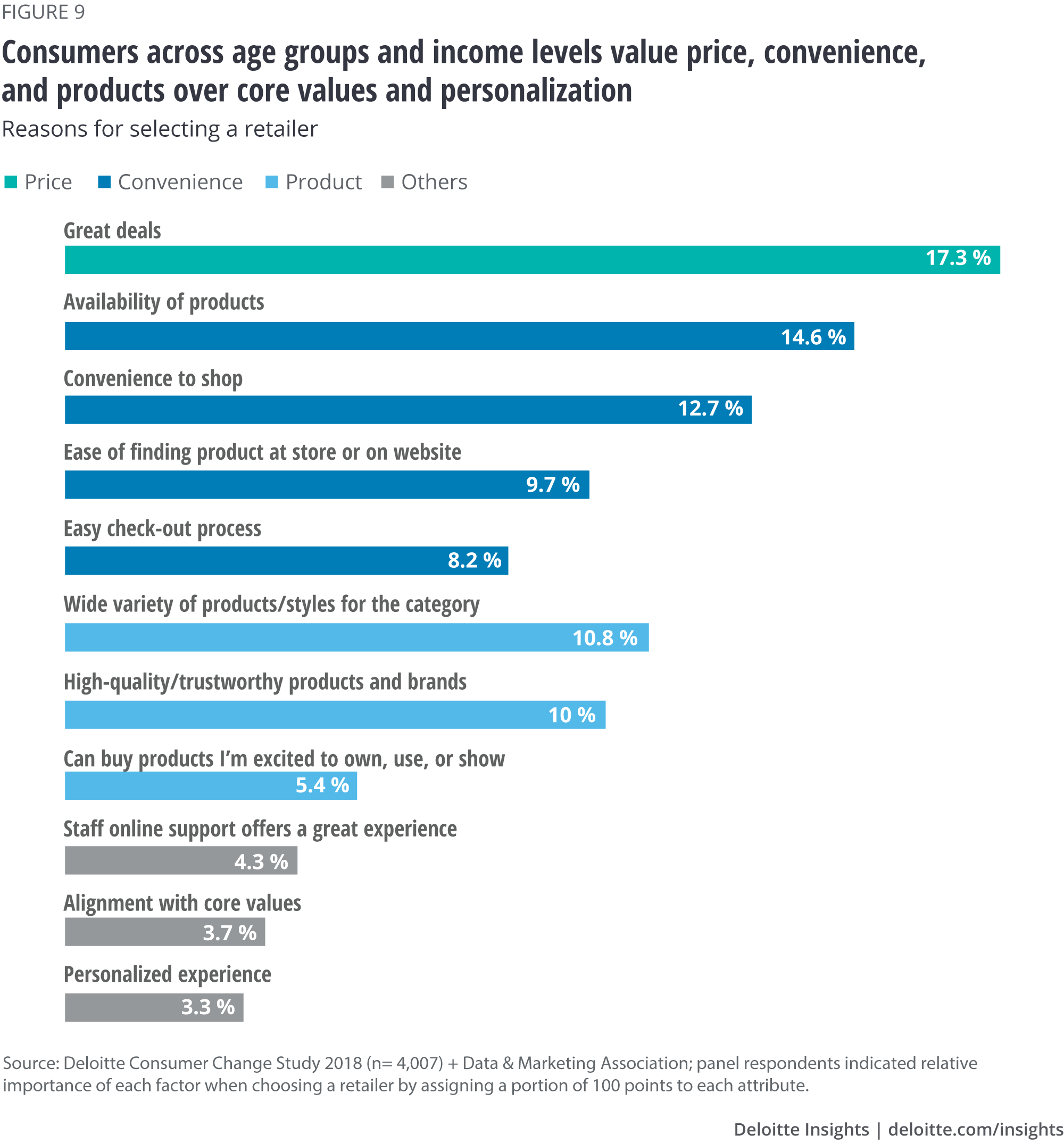

To this end, the survey helped us understand the changing consumer value set. We found that consumers still look to value, product, and convenience as the overwhelmingly important attributes while making decisions (figure 9). This finding is in line with the values that have been held by generations of US consumers.

In fact, often-noted attributes of the modern consumer like core values and personalized experiences ranked lowest among their priorities. While this finding doesn’t discount that some marginal attributes may have grown over time, the fundamental attributes that the consumer looks to today are similar to what we would have seen 50 years ago.

This preference holds true no matter how we slice the data—along the lines of age or income. Consumers across the board prioritize price, product, and convenience the most while evaluating purchasing options while alignment with core values and personalization matter the least in their retail experience. Even high-income millennials, who may be the outliers, follow this trend.

While what matters to consumers may not have changed significantly, we must remember that the marketplace today is a competitive battlefield. What is convenient or what offers value is relative, and hence these parameters are likely constantly changing in the mind of the consumer.

Consumers: The more they change, the more they remain the same

An analysis of the data and trends across demographics and consumer behavior brings to the surface a nuanced reality: The consumer is changing, but not necessarily in the ways we usually hear or think of.

The consumer is changing because the environment around them is evolving. If retailers and consumer product companies want to cater effectively to changing consumer needs and identify new pockets of opportunity, it is imperative for them to understand the demographic, economic, and competitive milieu that the consumer is reacting to.

Today’s consumer is more diverse than ever along the lines of race, ethnicity, income, education, rural-urban divide, migration, etc. These demographic forces have led to increased fragmentation, with the so-called “average consumer” now comprising distinct subsets of consumers who have increasingly distinct needs as well as competitive options to address their needs.

The consumer is changing because of the economic constraints they are operating under—including the rise in nondiscretionary expenses such as health care and education—and the growing bifurcation between income groups, which are having an impact on spending patterns. This is especially true of the low-income, middle-income, and millennial categories.

The changing consumer cannot be separated from the changing competitive market—they are two sides of the same coin.

However, the wallet share they spend on various categories—food, alcohol, furniture, food away from home, and housing—more or less remains constant. Also, despite the rise in online shopping, consumers are going more places than in the past.

It’s important to note that the consumer can’t be viewed in isolation from the changing competitive market, driven by the explosion and access to choices. The consumer is changing in reaction to the proliferation of competitive options in the market. This change has been made possible by technology, coupled with reduced barriers to entry, and the emergence of smaller players who are creating niche markets with more targeted offerings.

We must not confuse choice with change. In many ways the consumer of today is like the consumer of yesterday, they are a creature of the pressures they are under, coupled with the choices they have available to them.

Explore Retail and Consumer Products

-

Disruptive technologies in consumer products Collection

-

The consumer products bifurcation Article6 years ago

-

M&A for growth in consumer products sector Article6 years ago

-

New retail reinvigorates China’s imports Article6 years ago

-

Looking beyond millennials for brand growth Article6 years ago