Get going

Successful innovation programs are kinetic—that is, they are less focused on theoretical concepts, and more on traction and concrete outcomes.3 They carry a bias toward movement and forward progress. In turn, the data would suggest that those interested in improving their own business outcomes ought to themselves pivot from talk to walk.

Go now

Our survey suggests that the presence of a formal innovation program pays clear dividends. Compared to the average, high-growth companies are twice as likely to have a leading innovation capability. In addition, the age (and, by implication, maturity) of an innovation program further correlates with its demonstrated success. Organizations with a leading innovation maturity were almost twice as likely as the average to have revenue increase by more than 20%. Interviews bear this out. Mazziero notes, “Having a clear strategy is essential. Within our organization, we reverse engineered what we wanted from innovation and focused our energy on delivering quick results, like unveiling a mobile app.”

The interpretation here isn’t exactly rocket science: It’s better to have an innovation program than not, and it’s better to have a mature program than a nascent one. Akin to retirement savings, the best advice is therefore: a) start investing, and b) start yesterday. This recommendation might be more practically revised to: Start investing in your innovation capability today.

Go big

More than 300 years ago, Isaac Newton explained that Force = Mass x Acceleration, pioneering the idea that the force of an impact is a function of not just velocity, but of heft. As it turns out, this equation would appear valid for innovation impacts as well. High-performance innovation programs don’t just get going; they also go big. Tentative efforts—programs piloted with weak organizational commitment, awareness, and support—burn dimly, and briefly. Dedicated innovation leaders with bold mandates, dedicated resources, and hard capital to achieve them, are better equipped to avoid quicksand. As one innovation leader noted, “Many large companies get caught up in churn. Innovation can often be an experiment at best until it’s tested by an event like a recession or a CEO change.”

Business students the world over are familiar with the case study of 3M, whose bold innovation program was so central to its DNA, it developed the “Thirty Percent Rule,” wherein 30% of each division’s revenues must come from products introduced in the last 4 years.4 This is tracked rigorously, and employee bonuses are based on successful achievement of this goal. Such bold mandates put “new and improved” at the center of organizational operating models. Our survey data further bears this out: High-growth companies have a larger portion of their revenue coming from net new products and services.

Endemic to this “go big” theme are biases toward clarity, commitment, and accountability. Our data reveals that clearly defined teams led by clearly defined leaders with clearly defined mandates outperform diffused efforts. In fact, for many high-performers, innovation is not merely “a big deal,” but central to their brand, as they were much more likely to cite brand differentiation as a focus of their innovation agenda (48% of high-performers vs. 33% of average respondents). As Pushkarna, an innovation leader at Verizon, observes, “In today’s world, innovation is nobody’s exclusive business; it’s everybody’s business. For organizations to systemically benefit from innovation, you have to have teams dedicated to it and they should be rewarded for being catalysts of new thinking and connections in a world of silos, not just for ideas they help foster.”

In that vein, those with a leading innovation capability are much more likely to set targets and actively measure their ability to create and convert ideas into products (50% vs. 39% of average respondents).

Go together

Acceleration: check. Mass: check. But are your stakeholders, specifically your C-suite leadership, fully aware, let alone understanding, of the impact you are out to make? Our research demonstrates that organizations with a strong executive-level commitment to, and understanding of, innovation are more likely to report recent revenue growth. Moreover, those with a self-described leading innovation capability are more likely to say their C-suite is completely aligned with their innovation agenda (44% vs. 36% of average respondents).

When innovation teams are cloistered away, and work without alignment and support from the C-suite, their outputs, no matter how compelling, are more easily perceived as something to be passively critiqued.

Because early-stage innovation outputs are definitionally novel (i.e., unusual), and definitionally nascent (i.e., small potatoes relative to established lines of business), critical leaders receiving a pitch are sometimes wont to retreat to a defensive, “organizational antibody” response along the lines of: “This is interesting, but it won’t move the needle.” Or, invoking the classic venture capital line: Come back when you have more traction.”

“We learned that when you work too independently from the business, somebody owns every space we’re touching. There’s a certain human nature in pushing things away that you weren’t involved in from the ground floor,” says one of our interviewees.

By securing executive alignment early, and redoubling those connections often, the C-suite can be actively recast from critic to cocreator. Their posture, in turn, changes from “what’s wrong with your work?” to “how can we improve our work, together?” People support what they help create.

Keep going

A common finding in both our survey data and conversations is that innovation initiatives almost universally begin with optimism and goodwill, but many struggle to maintain momentum in the face of early setbacks. Our survey data shows that, on average, only half of all innovation efforts are achieving their desired value targets. This success rate increased, however, based on the percentage of time that a respondent spends on innovation.

Failure. In established organizations, we’re taught not to say the f-word. As heirs to historically successful organizations, enterprise leaders are often incented to not lose rather than win. Risks are costs and are thus minimized as opposed to managed in service of rewards and revenues. Alas, we cannot shrink our way to profitable growth.

In the startup community, failures are instead considered milestones to be celebrated.5 Not because founders seek to “lose,” but because they recognize that, in bringing new products and services to market, learning precedes earning. Startups call this iterative slog the search for “product market fit.” As an energy and resources innovation leader noted, “Innovation is to business-usual as chess is to checkers. You can’t win at chess without losing a few pawns.” Aravanis says: “Setting out to conquer what is difficult doesn’t always pay off, and fostering a company culture that punishes failure results in defensiveness and discourages tenacity.”

By embracing a founder—rather than steward—mentality, innovation leaders can engender an abundance, rather than scarcity, mindset. This involves a recognition that failure isn’t money wasted, but instead, invested—and that those learnings, made manifest in persistent pivots, is the recipe for (eventual) superior profits. According to our study, organizations with leading innovation maturity are more likely to consider failures as positive and celebrate lessons learned (78% vs. 54%).

“Innovation shouldn’t be pursued as a quick win—it takes years to be profitable,” says another innovation leader.

Let go

It’s been nearly 25 years since Clayton Christensen brought innovation to the boardroom with his bellwether classic, The Innovator’s Dilemma. Since then, a generation of theorists and practitioners have further formalized the space into the heavily stage-gated, carefully KPI’d discipline it is today. Eager to escape accusations of innovation being code for “playtime,” the field is now more buttoned-up, heavily degreed, and cuff-linked than many.

Our study reveals that despite this abundance of management best practices available today, leaders who proactively avoid micromanagement end up delivering more successfully. Erik Ross, head of Mergers & Acquisitions and Venture Capital at Nationwide Insurance, notes, “Innovation works when you push decision-making to the lowest level and let people make decisions … coach, don’t manage.” Indeed, another innovation leader adds, “As I’ve matured, I realized it’s my job to ask, ‘where are you stuck, and how can I help?’”

Survey data backs this up. Organizations with >20% revenue growth during the last 18 months were more likely to spread ownership of innovation throughout the organization (48% vs. 34% of average respondents). “The only way we create the next generation of innovators is by removing the constraints around what they think innovation means,” says Hartsock.

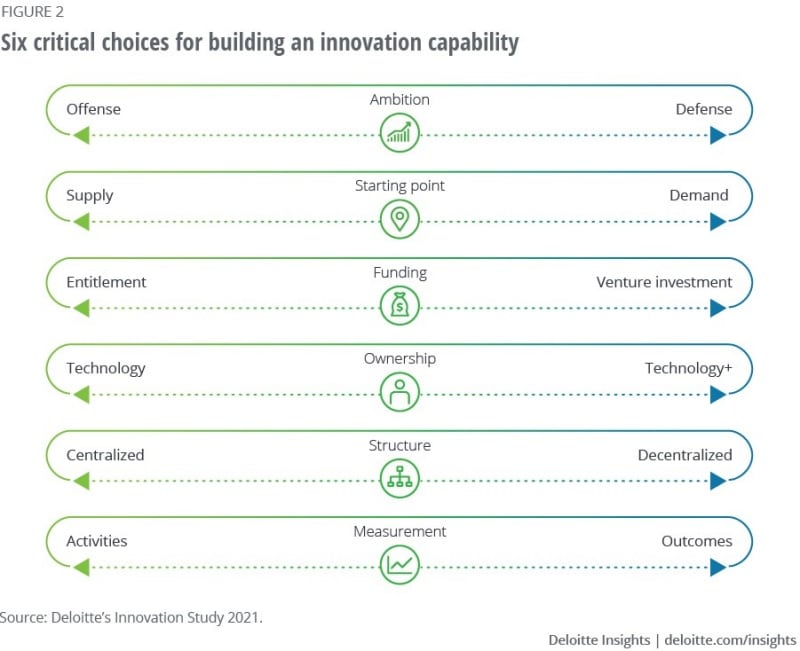

A reference model for corporate innovation

Given the preceding flurry of research findings, we don’t blame you if you’re wondering “now what?” For executives, information and insights, no matter how well-framed, are a means to an ultimate end: effective, efficient, profitable decision-making. In the spirit of this bias toward action, we present the following reference model for high-performance corporate innovation. Consider it a cheat-sheet of sorts, meant to inform, inspire, and guardrail your innovation efforts.