Where Do I Fit In? What Teams Lose When People Don’t Feel They Belong has been saved

Have you ever felt that you are exactly where you’re supposed to be? That you fit right in? That you’re part of something? This is what it means to belong. It’s a powerful feeling that is one of the most fundamental human needs and motivators. When a sense of belonging is absent, however, that can be powerful too.

This is the fifth and final post in a series introducing the findings from The Deloitte Greenhouse 2023 Barriers to Breakthrough Study,1 which explores the many different reasons beyond psychological safety that people might hesitate to contribute to a group discussion. I’ve already done a deep dive into how people’s perceptions about value and impact, as well as group dynamics can deter participation. Here I’ll explore one more category of potential deterrents, those related to belonging. These issues revolve around how people feel about and within the group.

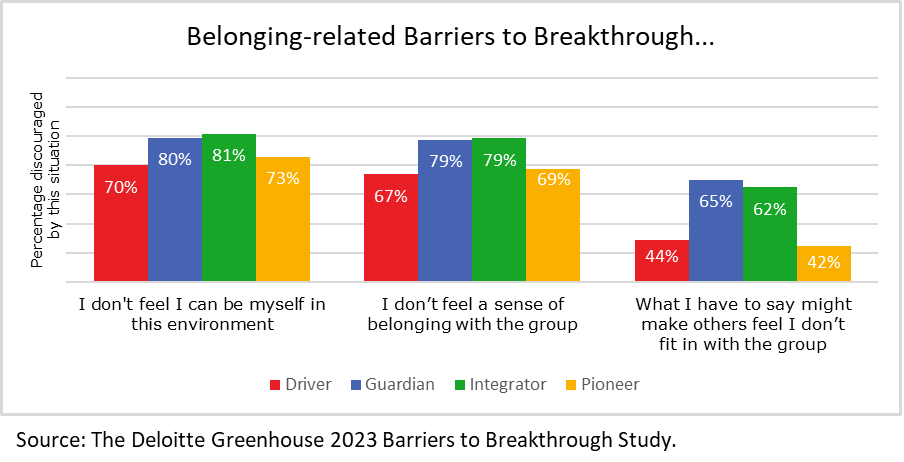

Our research found that people may stay quiet if they:

- Feel they can’t be themselves (76% might be discouraged from contributing).

- Don’t feel a sense of belonging with the group (73%).

- Think what they have to say might make others feel they don’t fit in (53%)

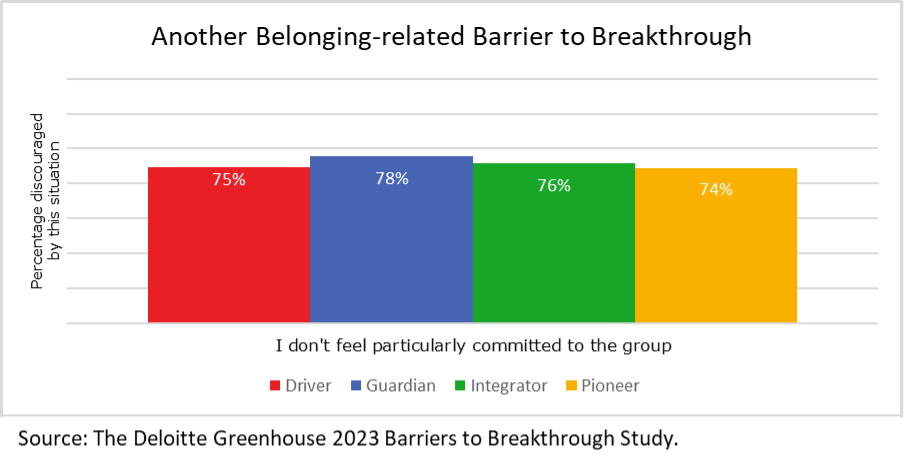

- Don’t feel particularly committed to the group (76%).

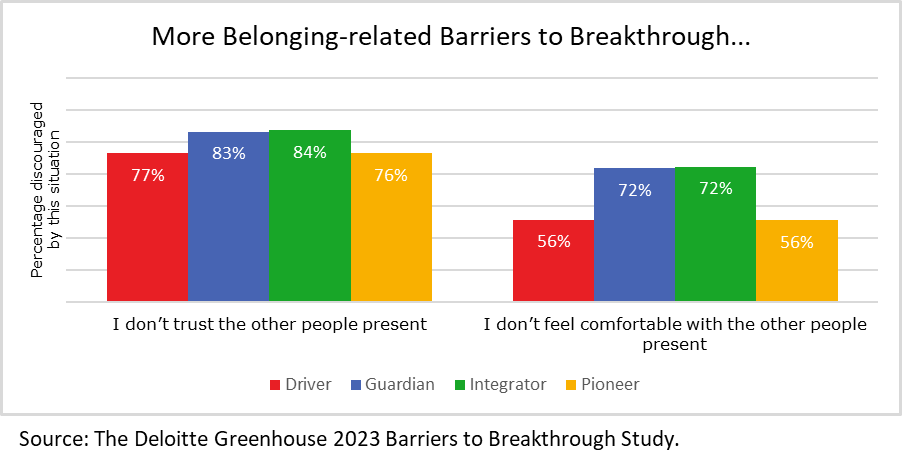

- Don’t feel comfortable with the other people present (64%).

- Don’t trust the other people present (80%).

What would it feel like to be your true, authentic self at work? As it turns out, many people don’t know. A recent Deloitte report entitled Uncovering Culture, found that 60% of professionals surveyed were downplaying at least one of their identities (a behavior referred to as covering). Among the identities commonly covered were those related to age, disability, gender, race/ethnicity, sexual orientation, caregiver status, and socioeconomic status. “Covering behavior is often a response to covering culture,” the authors suggest, defining covering culture as “an environment in which workers feel they would be penalized for displaying greater authenticity.”

Our Barriers to Breakthrough Study suggests that identities aren’t the only things people keep to themselves in a covering culture—when people feel they can’t be themselves they often decline to share their questions, opinions, and ideas. And Integrators and Guardians may be even more likely than Pioneers and Drivers to be discouraged by feeling it’s not okay to be authentic, by a sense they don’t belong, or by a fear that they won’t fit in.

So how do you know if your own team might have a covering culture? If people aren’t contributing in meetings that could be one clue, but as I’ve shared throughout this blog series, there are many reasons people may hesitate to contribute. To get a sense of whether a covering culture is a barrier on your team, you can start by asking yourself if you truly feel you can be authentic. If not, why not? But even if you feel okay to be yourself, others may not, and it’s possible you aren’t even aware of it. While pressure to cover may take the form of direct requests, it can also look like rewarding covering and penalizing failure to do so, or a generally unwelcoming environment for those don’t conform.

I’ve written before about how encouraging people to get real—to embrace vulnerability and show more of their authentic selves—can help teams get more creative together. But the authors of Uncovering Culture emphasize that the solution to covering isn’t just to encourage workers to “uncover” and “bring their full selves to work.” They state that “organizations cannot expect workers to be authentic at work unless they create the conditions in which that authenticity is valued.” So it’s not just about encouraging people to get real, but about creating a truly inclusive culture that supports doing so. To encourage people to share their perspectives in a group—especially perspectives that may go against the grain—people should feel confident that they belong, that it’s okay to be themselves, and that it’s okay to take risks. Creating that environment could pay off, because as the Uncovering Culture authors suggest, “the lower the demand for covering, the greater authenticity and more energy workers can expend toward creativity and productivity.”

How else might a covering culture affect people? It can decrease their level of commitment; 56% of respondents in the Uncovering Culture study said their commitment to the organization was negatively impacted by pressures to cover. Our Barriers to Breakthrough Study suggests that lack of commitment can discourage contributions to group discussions, and that this widespread deterrent is almost equally impactful across Business Chemistry types. I’ve written before about how this likely works; The Exit, Voice, Loyalty, Neglect (EVLN) model, based on the work of economist Albert Hirschman, proposes that people are more likely to voice concerns if they feel committed to the group and if they feel a sense of control. Without commitment, people are likely to either leave (exit) or reduce their effort (neglect).

Among the strategies you might consider to help increase people’s commitment are to position team members to play to their strengths, to better recognize them for their contributions, or to explore the connections between the team's purpose and individuals' sense of personal meaning.

Decreasing pressure to cover, increasing people’s sense of belonging, and encouraging their commitment can all be great strategies for getting people to contribute more, but none are simple or easy to do. There are, however, ways to encourage contributions even while your team is ramping up progress in those other areas. One way could be to assign roles, asking all team members to take on the task of adding a new, different perspective to what the team is already considering. Maybe one person will be assigned to focus on potentially negative long-term implications and another on the short-term. Or one team member might be asked to represent a customer point of view, and another, a regulator point of view. There are endless options. Even if people are still hesitant to contribute their own heartfelt opinions, best ideas, or most pressing questions, this activity could help get new ways of thinking into the mix.

Of all the potential deterrents to contributing that we’ve reviewed in this blog series, a lack of trust is among the more powerful. More than three quarters of people surveyed across all Business Chemistry types indicate they may be discouraged from sharing if they don’t trust the other people present. Even the arguably lower bar of not feeling comfortable with those people may keep a lot of people quiet, particularly Guardians and Integrators.

Building trust between people can facilitate more engagement, creativity, and breakthrough thinking, but we don’t necessarily all view trust in the say way. Therefore, sharing one’s own perspective about trust can be a very direct way to get real and create more trust at the same time. You may be familiar with the concept of love languages popularized by author Gary Chapman in his book The Five Love Languages. The idea is that people don’t all have the same preferences for how to give or receive love. Trust can be similar in that people don’t all have the same preferences for how to build trust or view indicators of trustworthiness in the same way. One person might interpret competence as a signal that someone is trustworthy and another might be looking for evidence of honesty. Talking about those preferences and differences can be a first step to understanding the best way to create trusting relationships with others. Here’s a technique for doing so that we share in our new book, The Breakthrough Manifesto: 10 Principles to Spark Transformative Innovation.

Explore trust

Step 1: Fill in the blanks to answer the following questions:

- One thing you can always trust me to do is _____ .

- I know I can trust you when ______ .

- If you ______, you will lose my trust.

- The most important thing someone can do to gain my trust is _____ .

Step 2: Pair up with someone and discuss where your answers are similar or different.

1 Between September 2019 and March 2020 and then again between September 2020 and July 2021, all respondents who completed the online Business Chemistry assessment were asked about the conditions that would discourage them from contributing in a group setting. More than 28,000 professionals from hundreds of organizations responded.

Get in touch

Suzanne Vickberg (aka Dr. Suz)

Dr. Suz is a social-personality psychologist and a leading practitioner of Deloitte’s Business Chemistry, which Deloitte uses to guide clients as they explore how their work is shaped by the mix of individuals who make up a team. Previously serving in Deloitte’s Talent organization, since 2014 she’s been coaching leaders and teams in creating cultures that enable each member to thrive and make their best contribution. Along with her Deloitte Greenhouse colleague Kim Christfort, Suzanne co-authored the book Business Chemistry: Practical Magic for Crafting Powerful Work Relationships as well as a Harvard Business Review cover feature on the same topic. She also leads the Deloitte Greenhouse research program focused on Business Chemistry and is the primary author of the Business Chemistry blog. An “unapologetic introvert” and Business Chemistry Guardian-Dreamer, you will never-the-less often find her in front of a room, a camera, or a podcast microphone speaking about Business Chemistry or Suzanne and Kim’s second book, The Breakthrough Manifesto: Ten Principles to Spark Transformative Innovation, which digs deep into methodologies and mindsets to help obliterate barriers to change and ignite a whole new level of creative problem-solving. Suzanne is a University of Wisconsin-Madison graduate with an MBA from New York University’s Stern School of Business and a doctorate in Social-Personality Psychology from the Graduate Center at the City University of New York. She is also a professional coach, certified by the International Coaching Federation. She has lectured at Rutgers Business School and several colleges in the CUNY system, and before joining Deloitte in 2009, she gained experience in the health care and consulting fields. A mom of two teenagers, she maintains her native Minnesota roots and currently resides in New Jersey, where she volunteers for several local organizations with a focus on hunger relief.