Can I Get a Word In? What Teams Lose When They Don’t Leave Space for Everyone | Deloitte US has been saved

Today more than ever, professionals are spending a lot of time in meetings. You might think everyone would be pretty good at it, but gathering a bunch of smart people to discuss an important topic isn’t enough to guarantee a productive meeting. Sometimes people aren’t engaged or don’t contribute much for a variety of reasons, as I’ve been outlining in this blog series. Other times just a few people dominate the conversation. And sometimes everyone tries to talk at the same time. None of these scenarios is ideal for encouraging an individual to share their heartfelt opinions, offer their best ideas, or ask their most pressing questions.

This is the fourth post in a series introducing the findings from The Deloitte Greenhouse 2023 Barriers to Breakthrough Study,1 which explores the many different reasons people might hesitate to contribute to a group discussion. I’ve already done a deep dive into how people’s perceptions about value and impact can deter participation. Here I’ll cover a third category of potential deterrents, those related to group dynamics. These issues revolve around the behaviors of team members and the resulting group atmosphere.

An intriguing aspect of group dynamics is that each person in the group is likely to be affected by those dynamics, but each person is also part of the dynamics. It’s like traffic—people often complain about traffic without recognizing that they themselves are part of the traffic. So, as you’re considering how the dynamics of your team might impact the likelihood of people offering up their opinions, ideas, and questions, it’s important to ask yourself how your own behavior might be contributing to those dynamics.

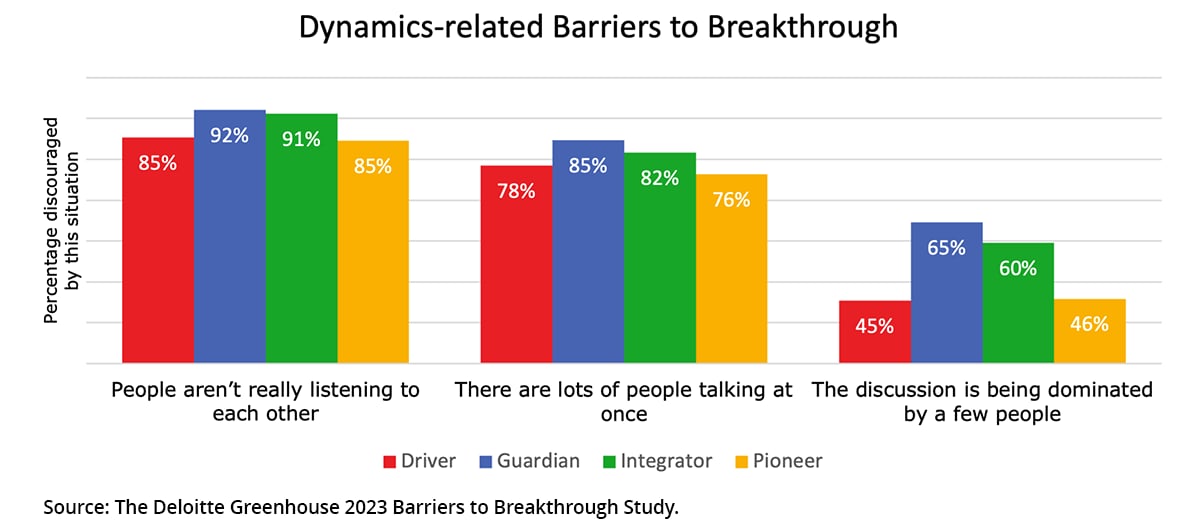

Our research found that people may stay quiet if:

- People aren’t really listening to each other (88% might be discouraged from contributing).

- There are lots of people talking at once (80%).

- The discussion is being dominated by a few people (54%).

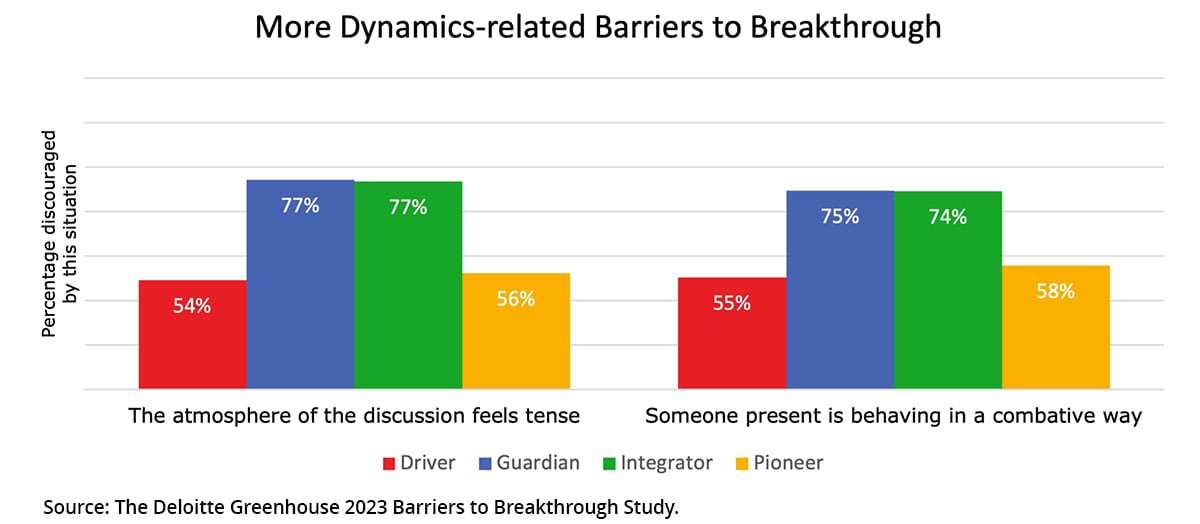

- The atmosphere of the discussion feels tense (66%).

- Someone present is behaving in a combative way (66%).

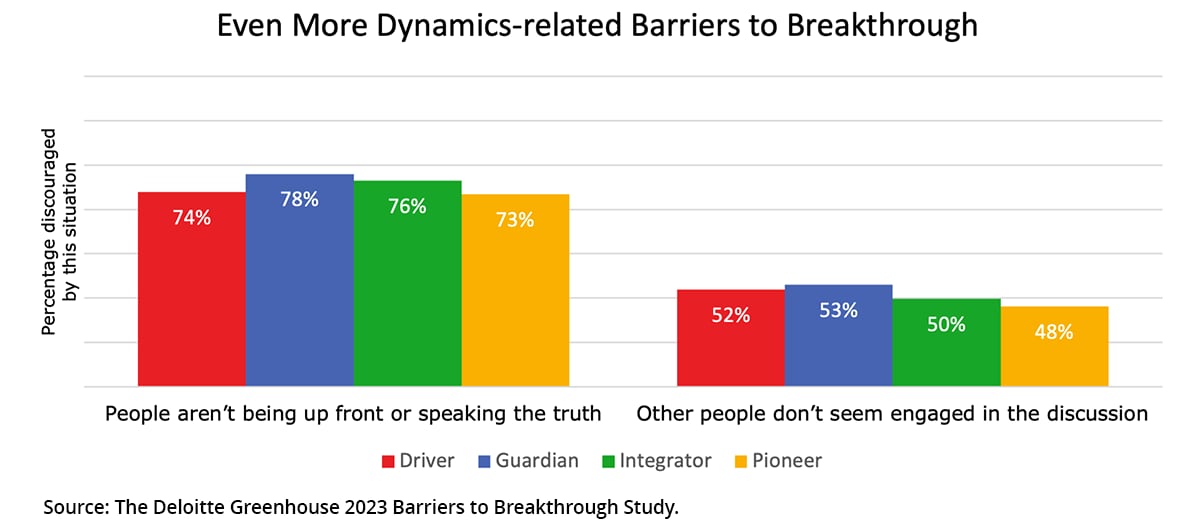

- People aren’t being upfront or speaking the truth (75%).

- Other people don’t seem engaged in the discussion (51%).

Is there space to speak on your team? Whatever your answer, do other team members agree? Let’s stick with the driving analogy for a moment. One person might think a parking spot is too tight and therefore won’t even attempt to fit into it, while another manages to work their way in. Or one driver may take longer than another to pull out onto a busy road because they need a bit more room to feel comfortable. If you feel there’s plenty of space to speak on your team, ask yourself if you might be more like those who park and pull out in tight spaces. Then ask yourself, Is there enough space for those who need a little more to be comfortable? If everyone talks at once, or a few people dominate the conversation, some team members—especially Guardians and Integrators—may not feel they have the space they need.

If you’re someone who easily finds enough space to speak up, there are things you can do to help others have more space. For one thing, you can simply pause a bit longer than you usually would before speaking. You could also say, “I’ve got an idea, but I’ve already spoken a lot, and I’d love to hear from a few others first.” In a recent Harvard Business Review article, Allison Shapira suggests the following if you and a colleague ever both start speaking at the same time: “If you have already spoken up in this meeting, concede to the other person by saying, ‘Please, you go first,’ and let the other person speak. If you have not yet spoken up in this meeting, say, ‘Thank you, I’ll be brief,’ and then continue.”

If you’re someone who often feels there’s not enough space for you to speak, there are things you can do to find more space. For one thing, whenever possible you could prepare in advance so you’re clear about what you want to say, which can make it easier to chime in. Shapira suggests you can even let the facilitator or team leader know in advance that you have something you’d like to contribute—that way they’ll be more likely to invite you into the conversation. She also suggests that a strategic filler word, like “actually” or “so,” lets others know you’d like to speak. When lots of people are talking at once, I sometimes revert to good old-fashioned hand raising. When I put my hand up, someone almost always directs attention my way and says, “Suzanne, did you want to add something?”

If you do attempt to speak, is anyone listening? I’ll trade in my driving analogy here for a dinner party. Have you ever been gathered around a dinner table and started to share an anecdote but then realized no one was listening to you? Did you barrel ahead and keep sharing your story even though you didn’t have anyone’s attention? Maybe, but probably not. More likely you stopped talking. You might even have felt a bit embarrassed. And then you may have waited for an opening and tried again, or possibly you just gave up. A similar thing can happen when teams are brainstorming, problem-solving, or discussing issues together. When someone offers something that no one seems to hear, they may close down, at least temporarily, and the team potentially loses out on whatever that person had to offer.

Eighty-eight percent of respondents in our study indicated they’re less likely to contribute to a discussion if they feel people aren’t listening to one another. I’ve written before about the importance of listening well and also shared some ideas for how to arrive at more equitable contributions. Both hinge primarily on paying attention.

Even if there is space to both speak and be heard, the atmosphere of the discussion may not feel equally welcoming for everyone. Do you love jumping into the fray for a vigorous debate? Not everyone does! There are sizable Business Chemistry differences here, with Guardians and Integrators being more likely to hesitate when the atmosphere feels tense or if they think someone is being combative. This is one of the reasons to silence your cynic. Healthy skepticism can be beneficial when the time and tone are right, but if you want everyone to chime in, it’s important that the environment remain open and welcoming.

If too much talking can be a problem, so can not enough. Often people look to others to gauge what they’re supposed to do. Think of the last time you went to a performance. People likely applauded at the end, and even if you didn’t realize it was the end, everyone else’s applause would likely have started you clapping, too. But have you ever heard someone burst out clapping when no one else did? Maybe it was you? Did the clapper carry on clapping or stop abruptly? Chances are they stopped. Something similar can happen in meetings. When others are actively engaging, it may feel natural to jump in, but if others are hesitating, one might perceive it as a signal that there is good reason not to jump. For about half the people we surveyed, this was enough to discourage them from speaking.

Honesty, too, can be a form of engagement. If it seems others aren’t being upfront about things, three-quarters of the people we surveyed would hesitate to contribute to the discussion. The Breakthrough Manifesto principle don’t play “nice” encourages being honest and direct but with caring. When one person is willing to say things how they see them, others will likely feel more comfortable doing so.

Together, these possible deterrents highlight some interesting tensions. You want people to be engaged, but you want them to listen to each other and not talk too much. You want them to be honest and upfront but not to be combative or create a tense environment. You want them to leave space for others but also to take advantage of space left for them. One way to find a balance among these tensions is to add a bit of structure that can engage everyone and help enable sharing honest and even critical perspectives in a way that might feel less threatening.

Have you ever said “just playing devil’s advocate” to make a criticism feel more palatable? This phrasing can allow people to distance themselves from a critical message and make it easier to share a perspective that might go against the grain. When done well—presenting a contrary opinion or alternative idea without attacking a person—it can be an effective technique to boost critical thinking, improve decision-making, and make ideas better.

People may sometimes be more honest about criticisms if there’s clear permission to do so or a structure that enables distancing from the criticism. If you want to discourage people from playing nice in regard to an idea your team is working on, there’s no need to involve the devil—ask them to play the role of your most likely critics. Doing so can give people permission to surface opinions or questions they might otherwise hesitate to share. Here’s a technique for doing so that we share in our upcoming book, The Breakthrough Manifesto: 10 Principles to Spark Transformative Innovation. It can offer an easier way for people to tell the truth while structuring sharing so that everyone participates and gets a chance to speak.

Find your Achilles’ heel

Step 1: Identify the likely worst critics of your idea (e.g., analyst community, board of directors, your boss, your employees, the press, your competitors).

Step 2: Put people into small groups, assign each a likely critic, and ask the group to look at your idea from that perspective. Expose the weaknesses in the idea by outlining the critic’s likely criticisms. What “gotcha” questions might that critic ask that you wish you’d researched? What would the critic say to negate your argument?

Step 3: Debrief together about what each small group came up with. Consider themes in the critiques—are any of them shared across critics?

Step 4: Identify ways to overcome the obstacles you’ve identified. Discuss patterns and themes that emerged, any assumptions that were revealed, and implications.

1 Between September 2019 and March 2020 and then again between September 2020 and July 2021, all respondents who completed the online Business Chemistry assessment were asked about the conditions that would discourage them from contributing in a group setting. More than 28,000 professionals from hundreds of organizations responded.

Get in touch

Suzanne Vickberg (aka Dr. Suz)

Dr. Suz is a social-personality psychologist and a leading practitioner of Deloitte’s Business Chemistry, which Deloitte uses to guide clients as they explore how their work is shaped by the mix of individuals who make up a team. Previously serving in Deloitte’s Talent organization, since 2014 she’s been coaching leaders and teams in creating cultures that enable each member to thrive and make their best contribution. Along with her Deloitte Greenhouse colleague Kim Christfort, Suzanne co-authored the book Business Chemistry: Practical Magic for Crafting Powerful Work Relationships as well as a Harvard Business Review cover feature on the same topic. She also leads the Deloitte Greenhouse research program focused on Business Chemistry and is the primary author of the Business Chemistry blog. An “unapologetic introvert” and Business Chemistry Guardian-Dreamer, you will never-the-less often find her in front of a room, a camera, or a podcast microphone speaking about Business Chemistry or Suzanne and Kim’s second book, The Breakthrough Manifesto: Ten Principles to Spark Transformative Innovation, which digs deep into methodologies and mindsets to help obliterate barriers to change and ignite a whole new level of creative problem-solving. Suzanne is a University of Wisconsin-Madison graduate with an MBA from New York University’s Stern School of Business and a doctorate in Social-Personality Psychology from the Graduate Center at the City University of New York. She is also a professional coach, certified by the International Coaching Federation. She has lectured at Rutgers Business School and several colleges in the CUNY system, and before joining Deloitte in 2009, she gained experience in the health care and consulting fields. A mom of two teenagers, she maintains her native Minnesota roots and currently resides in New Jersey, where she volunteers for several local organizations with a focus on hunger relief.