To Boost Creativity Silence Your Cynic | Deloitte US has been saved

(This is the second post in the Breakthrough Manifesto series, an exploration of Business Chemistry and how to tackle solving really tough problems. If you missed the introduction, read it here.)

"If you have built castles in the air, your work need not be lost; that is where they should be. Now put the foundations under them." – Henry David Thoreau

The second principle of the Deloitte Greenhouse Breakthrough Manifesto is silence your cynic. In other words, suspend disbelief and assume anything’s possible.

Quick, what's the No. 1 rule of brainstorming?

If you've been part of more than a few brainstorming sessions (haven’t we all?), you likely said (or thought) no judgement. Why is that the No. 1 rule? One reason is that fear of judgement can prevent people from sharing their ideas. And when you're aiming for creative problem-solving, you want everyone's ideas. Furthermore, when you don't pause to judge, you can come up with more ideas more quickly, and quantity is your friend in a brainstorming session. Creativity experts have said that the ideas don't usually start to get really creative until after the most obvious are out of the way. So not only might you get more ideas if you don't stop to judge, the ideas will likely be more creative.

Another reason to withhold judgement is that it can lead to dismissing an idea too quickly. It's typically not all that difficult to come up with reasons that any particular idea might not work, and if that's what you focus on, you may find that you soon run out of ideas. Judging an idea before you've let it sit awhile or spent some time exploring it may mean you miss an opportunity to see how it could work. Even totally unrealistic or off-the-wall ideas can have a kernel of practicality in them, and they might lead you down a path toward a related idea that works.

To be clear, the point is not for us to all silence our cynics always and forever—you don't need to hold a mock funeral for that part of your brain. If you did, you might end up repeatedly pursuing ideas that are just plain bad. There is definitely a time to take a critical look at any idea to understand possible negative implications or find the idea's flaws. But like when you strip away everything (the first Breakthrough Manifesto principle I wrote about), temporarily silencing your cynic can be highly beneficial, even when it’s difficult. (And sometimes it’s very difficult, at least for me. 😊)

Now, there are obviously people out in the world who can withstand judgement and cynicism about their ideas. The Internet is bursting with stories about inventions that experts said would never be a thing: lightbulbs, alternating current, telephones, cars, planes, personal computers, online shopping, microfinance, books about boy wizards, etc.! These examples illustrate how an unwavering belief in their own idea can enable creators to ignore the cynics who doubt them. It can be inspiring to read these believe in yourself stories, but we shouldn't let them fool us about the potentially destructive effects of judgement and cynicism, despite the difficulty of finding counterbalancing stories about ideas that were dismissed too quickly and therefore never changed the world.

It's even challenging to find stories about doubts that cropped up and were overcome, but these stories do exist. My favorite is the story of the Wright Brothers. Sure, like many other successful entrepreneurs, they ignored cynics who said that the mechanics of their plane were too complicated and would never work. But Wilbur Wright himself seems to have had a spurt of cynicism in 1901 after a few failed experiments. At that time he reportedly proclaimed to his brother Orville, "Not within a thousand years will man ever fly." Talk about cynical! But he didn't give up. Somehow he managed to silence his cynic—the brothers got right back to it and, within two years, had built their flying machine.

It seems clear that developing the first airplane or something else the likes of which the world has never seen may require silencing your own cynic while simultaneously ignoring all the other cynics around you. But even if your aspirations are the tiniest bit lower, the benefits seem worth the effort.

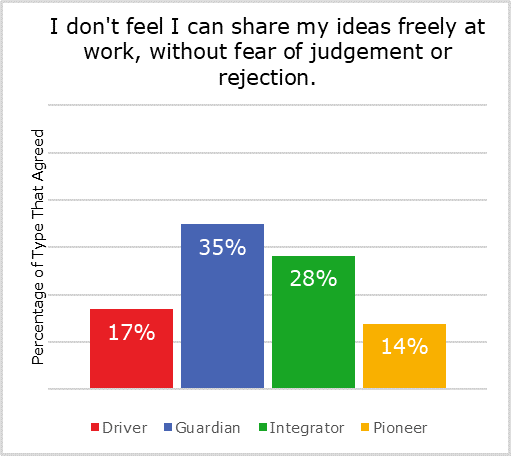

As I mentioned above, fear of judgement is one reason people sometimes don’t share ideas, and our research on psychological safety suggests that some Business Chemistry types may be more affected by this concern than others. We found that Guardians and Integrators are most likely feel they can’t share their ideas without the fear of being judged.

Given these findings, it may seem a bit ironic that Guardians are often seen as the most likely type to shoot down ideas, especially creative ones. Or maybe not. Possibly Guardians most fear judgement and rejection because they themselves are most likely to judge or reject others' ideas, and maybe their own as well. Guardians are known for thinking ahead about possible implications and spotting potential risk factors. In our book Business Chemistry, Kim Christfort and I wrote about the Guardian tendency to see and say every potential flaw in an idea. Doing so is a valuable contribution, even if it doesn't always make one popular, but our recommendation is that Guardians (and everyone else) be asked to delay their judgement so as not to shut down the creative process too early.

Moreover, we suggested in our book that Guardians and others who easily identify potential issues might be engaged early on to help solve for those issues. Putting that a bit differently, they could be encouraged to replace their typical orientation of defensive pessimism (identifying everything that could go wrong with an idea so that it can be mitigated) with strategic optimism (identifying and planning for what it would take to make an idea succeed). Part of the power of silencing your cynic lies in flipping from why something won’t work to what might make it work, and this mindset shift can really change the tenor of a conversation.

Integrators tend to be particularly averse to confrontation, and therefore might find it relatively easy to silence their cynic when it comes to other people's ideas. So, the challenge Integrators share with Guardians is to tackle their own fears about others judging their ideas. Engaging both of these types might require you to go to extra lengths to ensure everyone delays judgement, and to explicitly demonstrate that the judgement-free zone is real. One way to do so is to hold a round of brainstorming with the goal of coming up with the most ridiculous ideas possible, or you might provide prompts like "what are some ideas that might work, but are likely to be way too expensive?" or "what are some ideas that might work, but are likely to be logistically impossible?" Once people are on a roll coming up with ideas that are “unreasonable," they may feel freer to offer up other ideas that they're not yet sure about.

A similar approach might also work well with Drivers, who, like Guardians, are sometimes seen as erring toward pointing out what isn't practical, as opposed to letting discussions get expansive. One helpful exercise to engage these types might be to select some really out-there ideas, put people in pairs, then ask them to identify just one small change that would move the idea closer toward practicality. So instead of dismissing an idea, they're challenged to improve upon it.

Pioneers are known as the type who most values possibilities, and it can sometimes seem like their internal cynic is playing hooky. But I have heard from many of my Pioneer colleagues that they don't offer their most creative ideas in a group they think is likely to shoot them down. So, like Guardians and Integrators, Pioneers may be concerned about how others will receive their ideas, but for different reasons. If a Pioneer is thinking, “Ah, that person is just going to dismiss all my ideas anyway” or “They never want to do anything different than the status quo, so why bother,” they just may keep those creative ideas to themselves. The good news is that each of the previous suggestions will contribute to creating an environment likely to convince Pioneers, and others, that their ideas will not immediately be rejected. So urge Pioneers to keep offering up those crazy ideas, and show them they're appreciated.

Actions in summary for encouraging your team to silence your cynic:

- Ask Guardians to temporarily halt judgement and practice strategic optimism

- Help Integrators overcome fear of judgement by encouraging them to offer "unreasonable" ideas first

- Challenge Drivers to improve upon out-there ideas rather than dismissing them

- Urge Pioneers to continue offering their crazy ideas

For more on creative problem-solving, read my next post, which focuses on the third Breakthrough Manifesto principle, make a mess.

And if you simply can't wait to learn more about our Breakthrough Manifesto or how the Deloitte Greenhouse Experience might help your team attain breakthrough results, explore and get in touch here.

Get in touch

Suzanne Vickberg (aka Dr. Suz)

Dr. Suz is a social-personality psychologist and a leading practitioner of Deloitte’s Business Chemistry, which Deloitte uses to guide clients as they explore how their work is shaped by the mix of individuals who make up a team. Previously serving in Deloitte’s Talent organization, since 2014 she’s been coaching leaders and teams in creating cultures that enable each member to thrive and make their best contribution. Along with her Deloitte Greenhouse colleague Kim Christfort, Suzanne co-authored the book Business Chemistry: Practical Magic for Crafting Powerful Work Relationships as well as a Harvard Business Review cover feature on the same topic. She also leads the Deloitte Greenhouse research program focused on Business Chemistry and is the primary author of the Business Chemistry blog. An “unapologetic introvert” and Business Chemistry Guardian-Dreamer, you will never-the-less often find her in front of a room, a camera, or a podcast microphone speaking about Business Chemistry or Suzanne and Kim’s second book, The Breakthrough Manifesto: Ten Principles to Spark Transformative Innovation, which digs deep into methodologies and mindsets to help obliterate barriers to change and ignite a whole new level of creative problem-solving. Suzanne is a University of Wisconsin-Madison graduate with an MBA from New York University’s Stern School of Business and a doctorate in Social-Personality Psychology from the Graduate Center at the City University of New York. She is also a professional coach, certified by the International Coaching Federation. She has lectured at Rutgers Business School and several colleges in the CUNY system, and before joining Deloitte in 2009, she gained experience in the health care and consulting fields. A mom of two teenagers, she maintains her native Minnesota roots and currently resides in New Jersey, where she volunteers for several local organizations with a focus on hunger relief.