To Discover Possibilities, Strip Away Everything | Deloitte US has been saved

(This is the first post in the Breakthrough Manifesto series, an exploration of Business Chemistry and how to tackle solving really tough problems. If you missed the introduction, read it here.)

"In the beginner's mind there are many possibilities. In the expert's mind there are few." - Zen Master Shunryu Suzuki

The first principle of the Deloitte Greenhouse Breakthrough Manifesto is strip away everything. To do so, set aside what you think you know, question your assumptions, and adopt a beginner’s mindset.

I’ll admit right off the bat that this isn’t always easy for me to do, personally. If you've spent years in school or business getting smart about things (I have), why would you want to ignore what you know? (I really don’t.) However, it turns out that what you "know" can interfere with creativity and prevent you from seeing possibilities. The earned dogmatism effect describes a phenomenon that occurs when someone is labeled an expert—they tend to become more closed-minded. This effect is so strong that it can happen even if someone isn't actually an expert, but they have been experimentally manipulated into thinking they are. And when solving a tough problem, being closed-minded isn't to your benefit, especially since what you "know" is sometimes wrong. So I’ve learned to try on a beginner’s mindset when a problem is really tough to solve. If you’re not yet convinced, I hope you’ll read on.

Muhammad Yunus is an economist dedicated to tackling one of the toughest problems of all—poverty. Known as "the banker to the poorest of the poor," in 2006, Yunus was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize (along with Grameen Bank, which he founded) for his economic and social development work. His approach, which was foundational in launching the microfinance industry, emerged from questioning an orthodoxy of traditional banks. An orthodoxy is a belief, tightly held, about what is true, how things should be done, or why they should be done that way.

When Yunus started this work in the 1970s, the conventional wisdom was that poor women were not credit worthy and would not repay loans that weren't guaranteed with collateral. As a result, banks typically didn't provide such loans. Yunus wasn't a banker (yet), and he didn't see why this should be true. He wanted to help, and so he secured a line of credit by offering himself as guarantor and began providing loans so that women without means could start small businesses. Today Grameen lends more than $2.5 billion a year to 9 million poor women via collateral-free loans, and they report that their recovery rate is upward of 98 percent. What those traditional banks "knew" turned out not to be true, and it took a newcomer with a beginner's mindset to discover it.

Sometimes we’re forced into questioning our beliefs and assumptions. When the COVID-19 pandemic led to office closures and cancellations of events all over the world, orthodoxies held by many organizations were suddenly challenged and tested. Many who believed their employees could never work effectively from home entered into an involuntary experiment as their entire workforces began to do just that. Our own team in the Deloitte Greenhouse was compelled to strip away our long-held belief that we couldn’t deliver engaging experiences for our clients virtually. When we, all of a sudden, had little choice, we put aside what we previously "knew" and applied our energies to figuring out how to do so.

Of course, none of this means expertise isn't valuable, just that it can be a limiting factor if we don't learn to see past it or to set it aside temporarily when solving a problem. But it's not always easy to admit that what we think we know, we might not actually know. And doing so might be particularly difficult for those who have spent the most time learning what they know, or who see themselves as experts. And some Business Chemistry types are more likely than others to fall into this camp.

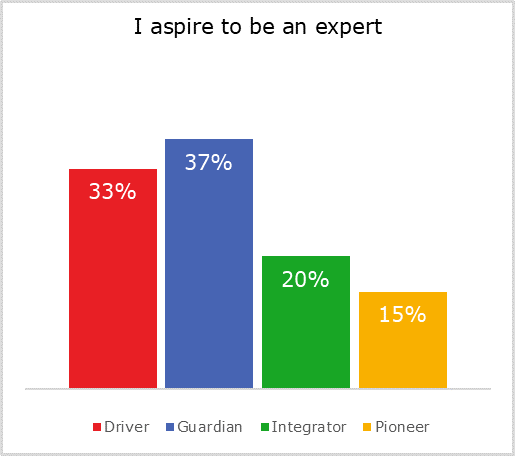

Our previous research shows that Guardians, followed by Drivers, aspire to be experts more than Pioneers and Integrators,1 and also that it’s more meaningful for these types to be recognized for their expertise.

It may be particularly important, then, if you want to encourage your team to strip away everything, to emphasize to Guardians and Drivers that you’re asking them to temporarily set aside or question what they know, not permanently disregard it. One particularly effective method for trying this approach is to engage in a flipping orthodoxies exercise. Here's how you might do it.

Let's say your organization has been struggling with burnout and low morale as of late, and leadership has tasked you with helping them solve for it. In recent organization-wide surveys, the expectation that people always be responsive to emails, even on weekends and vacation days, has been identified as a key contributing factor. An analysis of email traffic reveals that 97 percent of the employee population is active on the organization’s email system at least twice a day on their days “off.” And interviews with top leaders uncover a strong and wide spread belief that compulsive responsiveness is critical to the productivity of the organization. You have just identified one of your organization's orthodoxies, and not only does it limit your possibilities for solving the problem of burnout and low morale, but it also just may be the root cause.

To open up the possibilities for solutions, one method could be to ask those leaders to imagine that the opposite of their beliefs is true. What if teams were actually more productive when their members were able to totally unplug on days off? What possibilities would that suggest for solving the problem of burnout? What would that allow you to try for the sake of raising morale? You could ask the leaders to brainstorm ways to solve for the morale and burnout issues in the context of this alternate reality, where the opposite of their beliefs about productivity is true. Encourage them to list out as many ideas as they can think of, even if they seem crazy or impossible, because those thoughts might eventually inspire other ideas that are more practical.

This exercise is likely to work nicely with Pioneers, since they tend to revel in the realm of possibilities. They may really get into it if you're able to paint a compelling vision of what that alternate reality might look like. Or better yet, ask them to use their imagination to do so. A prompt might be "Imagine a world where people were most productive when they unplugged completely on their days off. What would that world look and feel like? What else might be true in a world like that?" While all the types can participate in this activity, Pioneers are likely to relish it and be particularly good at it, and the vision they paint might provide compelling inspiration for others.

When it comes to Integrators, one of the most effective elements of this method is that it addresses their need for context. When you ask someone to put aside what they know, it can leave a sort of vacuum that may be particularly challenging for Integrators to work within, since they typically like to understand how things are connected. But when you flip an orthodoxy and ask people to imagine an alternate reality, you're not just taking something away; you're replacing it with something else. So instead of problem-solving in the context of the current reality where we "know" that responsiveness at all times leads to productivity, or in the context of some other reality where we know nothing at all about productivity, you're asking people to problem-solve in the context of this clearly imagined alternate reality where we "know" that people are most productive when they can unplug on their days off. This new knowledge, even if it's imagined, can serve as an anchor for Integrators to solve around.

The same aspects of the exercise are likely to be valuable for Guardians and Drivers, because it helps to make the abstract more concrete, and concrete tends to be where they're comfortable. Furthermore, Guardians and Drivers are both likely to respond well to the clear structure of the exercise. You're not asking them to brainstorm willy-nilly, but in an organized fashion, in response to a well-defined scenario.

Once the group generates a long list of creative ideas, you could explore with them whether there might be reasons to question their beliefs about productivity in actual reality. Where do their beliefs come from? What evidence is there to support them? Is there any evidence that the opposite is actually true? Is there relevant research out there? Are there real-life examples that might put their beliefs to the test? And finally, would they be willing to experiment with some of the proposed solutions, testing and assessing whether they work to keep productivity levels up while improving morale and reducing burnout?

This way of backing into questioning their beliefs may be less threatening for Guardians and Drivers, who might hold a bit more tightly to what they likely see as their hard-earned wisdom. And they may be more willing to try out some of the new ideas when the effort is framed as an experiment with the promise that results will be analyzed and assessed.

Actions in summary for encouraging your team to strip away everything:

- Assure Guardians and Drivers that the request to put aside their expertise is temporary

- Ask Pioneers to paint a vivid picture of an alternate reality

- Encourage Integrators to anchor their thoughts within the context that alternate reality provides

- Engage Guardians and Drivers with a structured solution-generation exercise and back into questioning their beliefs

For more on creative problem-solving, read my next post, which focuses on the second Breakthrough Manifesto principle, silence your cynic.

And if you simply can't wait to learn more about our Breakthrough Manifesto or how the Deloitte Greenhouse Experience might help your team attain breakthrough results, explore and get in touch here.

Endnote

¹ 13,885 professionals were asked about their top career aspirations. In Christfort, Kim, and Vickberg, Suzanne. Business Chemistry: Practical Magic for Crafting Powerful Work Relationships. New York: Wiley, 2018, p. 118.

Get in touch

Suzanne Vickberg (aka Dr. Suz)

Dr. Suz is a social-personality psychologist and a leading practitioner of Deloitte’s Business Chemistry, which Deloitte uses to guide clients as they explore how their work is shaped by the mix of individuals who make up a team. Previously serving in Deloitte’s Talent organization, since 2014 she’s been coaching leaders and teams in creating cultures that enable each member to thrive and make their best contribution. Along with her Deloitte Greenhouse colleague Kim Christfort, Suzanne co-authored the book Business Chemistry: Practical Magic for Crafting Powerful Work Relationships as well as a Harvard Business Review cover feature on the same topic. She also leads the Deloitte Greenhouse research program focused on Business Chemistry and is the primary author of the Business Chemistry blog. An “unapologetic introvert” and Business Chemistry Guardian-Dreamer, you will never-the-less often find her in front of a room, a camera, or a podcast microphone speaking about Business Chemistry or Suzanne and Kim’s second book, The Breakthrough Manifesto: Ten Principles to Spark Transformative Innovation, which digs deep into methodologies and mindsets to help obliterate barriers to change and ignite a whole new level of creative problem-solving. Suzanne is a University of Wisconsin-Madison graduate with an MBA from New York University’s Stern School of Business and a doctorate in Social-Personality Psychology from the Graduate Center at the City University of New York. She is also a professional coach, certified by the International Coaching Federation. She has lectured at Rutgers Business School and several colleges in the CUNY system, and before joining Deloitte in 2009, she gained experience in the health care and consulting fields. A mom of two teenagers, she maintains her native Minnesota roots and currently resides in New Jersey, where she volunteers for several local organizations with a focus on hunger relief.