Embedding trust into COVID-19 recovery Four dimensions of stakeholder trust

12 minute read

23 April 2020

As resilient leaders seek to shepherd their organizations and stakeholders through the COVID-19 crisis, trust will be critical to the recovery—specifically, four dimensions of trust.

Introduction

Trust is the connective tissue that binds together everything that we do: our relationships, our actions, our expectations of others. We expect institutions, businesses, and other organizations to deliver on their promises and behave responsibly. We expect that we can move around our communities safely, depend upon our relationships, and rely on certain truths.

Learn more

Learn more about connecting for a resilient world

Learn about Deloitte’s services

Go straight to smart. Download the Deloitte Insights app

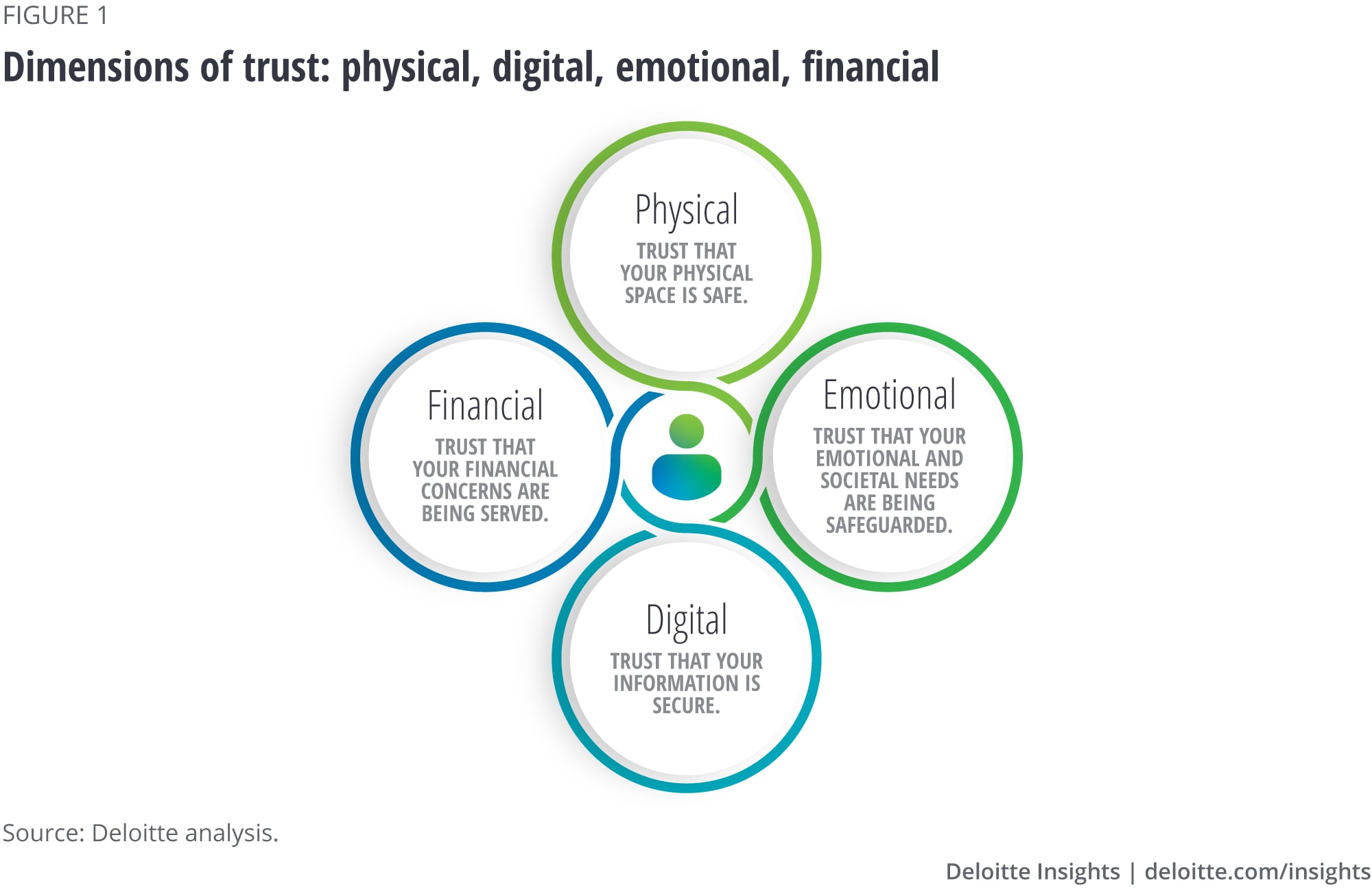

The COVID-19 pandemic has been a shock to our collective systems—and a catalyst to rebuild trust. As resilient leaders seek to shepherd their organizations and stakeholders safely through the COVID-19 crisis, trust will be more critical than ever, as recovery without trust rests on shaky ground. In order to rebuild trust among stakeholders and best position their companies to thrive in the long term, leaders must focus on four dimensions of trust: physical, emotional, financial, and digital.

The challenge of trust

Research shows that the presence of trust brings a wellspring of positive outcomes: Communities with a strong sense of trust are better able to respond to crises.1 Trust is associated with stronger economic growth,2 increased innovation,3 greater stability,4 and better health outcomes.5

Yet trust in institutions that are supposed to steward and safeguard us—businesses, government, media, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), and others—has been on the decline for many.6 Driven in part by increasing polarization, rapid technological change, the spread of disinformation, and new expectations on both the workforce and society, fewer than 20 percent of individuals globally feel trust in the current economic system.7 A 2020 study found that no institutions, from businesses and government to NGOs and media, were seen as both ethical and competent, and none were considered fair.8 While trust in institutions meant to safeguard us has declined, fears about jobs, the economy, the future, the ability to have access to the truth, and inequality have increased.9

In times of crisis—such as a pandemic—tapping into the wellspring of trust becomes paramount to disseminating critical information, maintaining confidence, and containing illness. Distrust, on the other hand, can have the opposite effect.10 Calls to “flatten the curve” and engage in social distancing mean that we have to trust each other—perhaps much more than we have in the recent past—to act for the greater good. It is therefore now more important than ever to prize trust and infuse it in all that we do as individuals, and as business leaders. Indeed, being intentional about trust during a time of crisis can set apart a business leader who competently steers his or her company through these uncertain times. In other words, a trusted leader is most often a resilient leader.

The meaning of trust

Trust is defined as “our willingness to be vulnerable to the actions of others because we believe they have good intentions and will behave well toward us.”11 We are willing to put our trust in others because we have faith that they have our best interests at heart, will not abuse us, and will safeguard our interests—and that doing so will result in a better outcome for all. Institutional trust refers to trust in formal institutions: systems, governments, companies, and organizations. Social trust refers to faith in people; it connotes social ties and interpersonal trust between individuals within communities, workplaces, and stakeholder groups.12 Social trust is often considered the fabric that binds us together, and ensures societies, economies, and systems can function well—or not.13

At the same time, broken trust can have a dramatic and quantifiable effect: As a recent Deloitte study reported, three global companies embroiled in scandal lost 20–56 percent of their market cap relative to their peers over a period of three months to two years, and fell behind the comparable industry index by 26–74 percent.14

The dimensions of trust

Business leaders have many stakeholders, each with different concerns (see sidebar, “The ecosystem of trust”). What are the levers of trust that organizations can pull to manage stakeholders: customers, communities, employees, and other ecosystem partners such as suppliers, governments, and shareholders?

As business leaders look to instilling and building trust in their stakeholders post–COVID-19, they should place themselves in their stakeholders’ shoes and consider the needs of each across four dimensions of trust: physical, emotional, financial, and digital (figure 1).15 What will each stakeholder group be asking themselves? What will concern them most? Developing strategies in each of these areas and communicating them early, often, and honestly will be critical. In our analysis, we have found this model applies to all stakeholders; each will likely have diverse perspectives that require innovative solutions.

Physical trust: Can stakeholders trust that physical locations are safe?

- Customers and communities: Can I feel safe gathering in groups or going to places where resources are shared and touched by many?

- Employees: Can I feel safe at my workplace?

- Ecosystem partners: Can I feel safe that partners are taking precautions in their facilities to protect me?

Social and physical interaction are an essential part of the human experience. Mental strain associated with COVID-19–related social distancing has been noted in every affected location, from Italy and South Korea to London and New York City.16 Further, the length of lockdowns and quarantines is directly correlated with mental health.17

While many are anxious to return to “normal life,” the return to pre–COVID-19 physical interaction will likely depend on individuals’ ability to trust that they will be safe from infection in public spaces, whether offices, in the case of employee stakeholders, or other physical locations, in the case of consumers. The question of physical safety will likely be even more vital in industries where physical contact is necessary and goods and assets are shared and touched by many, such as travel and tourism, retail, and dining.

As recovery continues and workers are reengaged, leaders will also need to communicate to and reassure the workforce that they are returning to safe environments. Moreover, employees whose work is considered essential and who must be physically present at a workplace throughout the recovery will need to trust that they can safely do their jobs, and that risk of infection is minimized.

Physical trust in practice

Many organizations are taking steps to instill that trust in their workforce: Some American, Canadian, and UK retailers have repurposed plexiglass from retail displays to shield cashiers or increased pay to account for the increased risk.18 In China’s Hubei province, a leading grocery retailer equipped its employees with protective gear, including masks, gowns, and gloves; offered in-store giveaways of masks to customers; disinfected its storefronts; and restricted foot traffic in its stores. In Japan, companies are leveraging new facial recognition technologies to ensure workers do not have to remove masks to be identified upon entering an office or building and are using motion-sensing technologies to enable touchless interactions in elevators and other spaces.19

Actions such as regularly checking body temperature and communicating openly about current infection status among employees can also help build and restore trust; some organizations and facilities in China, Japan, and South Korea are following this approach.

Emotional trust: Can stakeholders trust that their emotional and societal needs are being safeguarded?

- Customers and communities: Can I trust that the company will tell me the truth and do right by me? Can I feel safe its goods are safe, and it is treating its workers well? Can I see that it is doing all it can to help in this crisis?

- Employees: Can I trust that I will be empowered to do my job? Can I feel safe that I can speak up and ask openly about my job without fear of reprisal, and will receive an honest answer?

- Ecosystem partners: Can I build trust without face-to-face interactions? Can I find novel ways of working together that benefit all?

The speed, unpredictability, and magnitude of change due to the COVID-19 pandemic has profoundly impacted many individuals’ level of anxiety and sense of safety.20 For some, it can feel difficult to know where to turn or where to find support. Business leaders can help build trust by focusing on the intersection of their capabilities and the social good they can do for their customers and communities. Putting communities’ needs at the forefront demonstrates a commitment to social responsibility over short-term profits, fortifying trust in the long term.

With respect to employees, the equation is more complex. Research has shown that psychological safety—the ability to feel comfortable giving and receiving candid feedback, asking difficult questions, and making mistakes—is an important asset of organizational culture.21 This type of culture is based on trust: Individuals need to feel safe to ask questions such as “What will happen to my job?” and communicate openly and honestly without fear of reprisal. Further, enhancing remote work capabilities can help many employees feel more connected and secure about doing their jobs.

Emotional trust in practice

Some organizations have emphasized clear communication to convey deep emphasis on their purpose. For example, in China, a leading grocery retailer proactively shared information about inventory levels and pricing to the public, adjusted opening hours, and promised not to increase prices on staple items. It also put in place measures to discourage hoarding, such as removing stacked displays and placing more products on shelves so customers could trust they would not run out of inventory.22

Many companies are also refocusing their capabilities to assist consumers and the community in recovery. Breweries, distilleries, and packaging manufacturers in North America, Europe, and Australia have shifted manufacturing to produce hand sanitizers and masks for front-line health care workers and consumers.23 Some companies have made their virtual meeting capabilities and online educational tools available for free to schools struggling to adapt to social distancing, while media companies throughout North America and Europe are lifting their paywalls for COVID-19–related reporting in the interest of sharing crucial information.24

Among communities, suppliers, and other stakeholders, leaders can aim to build trusted alliances rather than engaging in a competitive response. This approach can lead to some novel alliances; many organizations are collaborating with competitors to ensure stakeholders’ needs are being met, strengthening trust for all. For example, leading technology competitors have launched a joint venture to help health care leaders and the public sector digitally track the spread of COVID-19.25 In the physical world, competitive regulations were temporarily relaxed in the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, and Germany to allow competing supermarkets to work together by sharing data to avoid food shortages, pooling staff, and sharing distribution centers and delivery trucks.26

Financial trust: Can stakeholders trust that their economic and financial concerns are being served?

- Consumers and communities: Can I trust that this company will not take advantage of this crisis to exploit me?

- Employees: Will I lose my job? Can I trust my company will do all it can to support me, and be honest about its intentions and economic health?

- Ecosystem partners: Can I trust that this company will be understanding of the challenges I am facing, or when I cannot meet its demand/needs given my own constraints in this crisis?

“This global pandemic and economic crisis has impacted every home,” said Dave McKay, president and CEO of Royal Bank of Canada. “People’s life savings are being affected. Young people are just as worried about their future as those nearing retirement. And thousands of entrepreneurs, many who have put decades into their businesses, are worried about surviving the weeks and months ahead. … In times like these, people remember who was there for them.”27

At the forefront of many minds is financial health, during and post–COVID-19. Stories abound of bad actors exploiting the situation—for example, price gouging on necessary items such as toilet paper and hand sanitizer.28 At the same time, other companies are working to instill financial trust. With respect to the workforce, concerns about job loss are high, compounded by uncertainty regarding how long the recovery will take and reports of sharply spiking unemployment rates.

However, it will also be important to consider the other side of the coin. An opaque approach or unkept promises can lead to loss of trust. Therefore, communications should be grounded in clear, achievable actions, with a focus on maintaining integrity in the face of financial uncertainty.

Financial trust in practice

One insurance company announced that it plans to refund 15 percent of automotive insurance premiums to its US policyholders, as lockdowns have led to significant decreases in driving.29 Some banks have offered to defer loan payments, have extended new lines of credit, or are working to provide flexibility to small business owners.30

With respect to other stakeholders in the ecosystem, organizations may need to collaborate with suppliers and trust each other in ways they have not had to before; issues such as limited inventory among suppliers or the need to prioritize production of certain goods over others due to the pandemic may mean that some companies will need to shift their plans for the greater good.31

Digital trust: Can stakeholders trust that their information is secure?

- Customers and communities: Can I trust that cybersecurity is a priority and that my transactions, information, and personal data are correct, secure, and private?

- Employees: Can I trust that my work-related data is secure and private, that networks will function, and that cybersecurity measures are in place?

- Ecosystem partners: Can I trust that measures are being taken to protect my proprietary information, ensure integrity of the transactions, and that service levels are met as business interactions are increasingly virtual?

Data security and privacy constitute significant issues for trust. It will, thus, be critical for leaders—particularly in the public sector, technology, and telecom—to instill trust that personal data is being properly handled and safeguarded during the Recover phase, and, where promised, personally identifiable data is being anonymized and deleted after the relevant period of time. This promise must be clearly communicated. Additionally, while it is too early to tell whether the shift away from physical interactions toward predominantly digital will be permanent, the ethical questions that this evolution raises, such as accuracy, use, and handling of data, must be considered.

Further, the need for social distancing has accelerated digitization, creating new considerations around the safe and ethical use of technology and data as well as cybersecurity, including the detection and prevention of privacy incidents, fraud, and misuse of technology and data. Leaders must consider cyber risks across their key stakeholder network: third parties, suppliers, partners, customers, employees. Some of these questions will be new to leaders who have not historically considered their organizations to be “tech companies,” and who have not had to consider questions of privacy, security, or monitoring as much as they do now that their work and interactions are predominantly virtual.32 Leaders that get the digital dimension right will build trust with their stakeholders and drive sustainable success.

Digital trust in practice

Digital privacy constitutes a particular concern in a post–COVID-19 world where countries, regions, and markets on nearly every continent—China, Japan, South Korea, Singapore, Taiwan, Austria, Israel, the United States, and Belgium, to name a few—have tracked mobile users' location history in an effort to understand and curb COVID-19’s spread.33 One digital company offers a site that tracks the anonymized, aggregated movements of individuals globally to show overall increases or decreases in gatherings.34 While the data is not individually identifiable, it can raise potential concerns around privacy and location tracking. The lack of clear and consistent policy and communication across regions and countries makes this all the more challenging.

The ecosystem of trust

The Business Roundtable, an association of CEOs, published updated governance in August 2019 affirming that shareholder primacy should be superseded by a broader commitment to stakeholders: customers, communities, employees, suppliers, government, and shareholders.35 The emphasis on stakeholder capitalism at the 2020 World Economic Forum solidified that this is not just a regional issue but a global one. In other words, trust extends to multiple populations throughout a business leader’s—and organization’s—ecosystem. Each stakeholder group will face different concerns.

Sandra Sucher, professor of management practice and the Joseph L. Rice III Faculty Fellow at Harvard Business School, notes, “Trusted companies know how to balance the trust of all their stakeholders. They act in favor of one group while still serving the interests of others.”36 In one example, a global hotel and resort chain that needed to furlough workers connected its shutdown teams with other companies that needed help in the short term to deal with surges in demand.37 In this way, they were able to help peers in other industries while demonstrating a commitment to keeping their workforce engaged, fostering trust with stakeholders both internally and externally.

Being trustworthy

“In the next … pandemic, be it now or in the future, be the virus mild or virulent, the single most important weapon against the disease will be a vaccine. The second most important will be communication.”—John M. Barry, author of The Great Influenza: The Epic Story of the Deadliest Plague in History38

Business leaders cannot control the pandemic, nor can they control other external forces beyond their sphere of influence. Therefore, leaders must focus on the areas they can control—such as product and service quality, treating their employees well, commitment to behaving ethically and transparently, and digital competence—and infuse their actions in those areas with purpose and integrity.39

Being trustworthy involves approaching stakeholders’ needs and concerns across each of the four dimensions of trust in two ways: with competence and intent. Put simply, competence refers to the need to “do it right”: to follow through on what you say you will do in an effective, meaningful, impactful way. Intent refers to the meaning behind a business leader’s actions: taking decisive action from a place of genuine empathy, transparency, and true care for the difficulties stakeholders are facing. These actions not only fulfill a company’s promise—they also strengthen relationships.

As they consider the best ways to move forward in a manner that instills trust in their stakeholders, business leaders can ask themselves the following questions:

- Which dimensions matter most to each of our stakeholders right now? What will likely matter to them as we turn the corner to Thrive?

- Are we taking this action with the right intent? Does it fit with our organization’s ethos?

- Can we competently deliver on what we are promising to our stakeholders?

- Are we communicating our intentions clearly and transparently to our stakeholders—even when we don’t know all the answers?

- How are we monitoring and measuring our progress in addressing stakeholders’ needs across the four dimensions of trust?

Consistently asking these questions will help enable leaders and their organizations to adapt quickly to the ever-changing needs of their stakeholders, as well as the ever-evolving external forces shaping their perspectives.

Even as we enter recovery, we may not go back to how we were before. A return to “normalcy” will likely not happen quickly, and patience will be required. Some industries may have higher hills to climb toward recovery. And some lessons learned by necessity during the Respond phase—such as remote work, virtual collaboration, increased digitization, greater flexibility in working with partners and stakeholders—may result in more permanent shifts for many organizations. These shifts will vary by industry, company, and geography, but resilient leaders must be prepared to adapt as needed to best serve their stakeholders and ready their organizations to move forward toward a new normal.

Balancing stakeholder trust is one of the most important items on business leaders’ agenda. They should do so with a vision and purpose grounded in trust—and deliver it competently, openly, honestly, and with clear intent. If done well, this approach has the potential to accelerate a company’s recovery and enable it to thrive and shape the future. Times of crisis present an opportunity to lead with trust. Doing so will better prepare leaders’ organizations to maintain business continuity, to learn and emerge stronger—and to thrive.

More on COVID-19

-

Connecting for a resilient world From Deloitte.com

-

The economic impact of COVID-19 (novel coronavirus) Article5 years ago

-

Governments’ response to COVID-19 Article5 years ago

-

Potential implications of COVID-19 for the insurance sector Article5 years ago

-

COVID-19 and the investment management industry Article5 years ago

-

COVID-19 potential implications for the banking and capital markets sector Article5 years ago