Quantifying risk: What can cyber risk management learn from the financial services industry? has been saved

Quantifying risk: What can cyber risk management learn from the financial services industry? Deloitte Review issue 19

26 July 2016

Quantitative models to measure cyber risk—the same kinds of models widely used by financial services firms—are starting to gain broader acceptance. But risk managers may be led astray if they rely too much on models out of context. What lessons in effectively using models does the financial services industry hold for cyber risk management?

The financial services industry is known for its sophisticated approaches to managing the risk associated with the financial instruments it sells. It’s an industry imperative: No informed customer would invest with a financial services firm that lacked provisions for guarding against extensive losses. Among these approaches, one of the most widespread is the use of “fantastically complex mathematical models for measuring the risk in their various portfolios.”1 These models even allow firms to assign a dollar value to that risk—effectively allowing portfolio managers to quantify the risk their investments generate.

The financial services industry is known for its sophisticated approaches to managing the risk associated with the financial instruments it sells. It’s an industry imperative: No informed customer would invest with a financial services firm that lacked provisions for guarding against extensive losses. Among these approaches, one of the most widespread is the use of “fantastically complex mathematical models for measuring the risk in their various portfolios.”1 These models even allow firms to assign a dollar value to that risk—effectively allowing portfolio managers to quantify the risk their investments generate.

Today, many organizations are entering a new risk domain—cyber risk management—that exhibits many of the same characteristics as financial risk management in the financial services industry. While the comparison between the two may seem far-fetched at first, there are, in fact, a number of parallels that suggest that experiences in one domain can hold valuable lessons for the other. These parallels include:

Learn More

View the Dbriefs webcast

Explore the Cyber Risk Management collection

Read Deloitte Review

- Complexity. For years, the financial services industry has used complex financial instruments where risks arise from the interaction of many disparate factors. In the cybersecurity context today, businesses are incurring increasing risks through their use of complicated computer system architectures and adoption of cloud computing, bring-your-own-device IT models, mobility, and other digital advancements. Just as with highly complex financial instruments, the intricacies of the interactions among risk factors can make it difficult to identify and assess relevant risks. While risk models and other quantitative metrics and qualitative sources can provide warning signs, business leaders in both the modern financial services and cyber risk eras face the distinct possibility that these warning signs may not always be clearly understood.

- The use of models for risk management. Financial institutions use a variety of risk models, some long established and others relatively new. Some risk management leaders today who attempt to apply quantitative models to measure cyber risk rely on some of those same types of models. The danger here is that senior executives and boards may overlook the complexity and, in some cases, limits of these models. The simplicity of many of these models’ outputs—often a single, easy-to-fathom number—can mask the intricacy of the models’ inputs and analysis process, potentially prompting executives to assume their quality and completeness rather than carefully scrutinizing the models’ validity under particular circumstances.

- Potential systemic failures. In the financial services industry, there is constant recognition that financial institution failure can have ripple effects across borders, entire segments of the financial services industry, and, ultimately, much of the rest of the economy. Today’s cyber risks potentially threaten entire ecosystems, including business, government, and societal.

Of course, public officials and leaders in many private sector industries are highly aware of cyber risks. Cybersecurity spending worldwide continues to grow, and is predicted to reach $170 billion by 2020, up from $75.4 billion in 2015.2 Yet many struggle to determine the scope of those risks and how to appropriately balance risk-reward trade-offs.

It is this drive to quantify cyber risk and calculate the return on investment in cybersecurity that is fueling efforts to put a number to the extent of a company’s cyber risk—paralleling the importance financial services firms place on quantifying financial risk. Investment, banking, and insurance executives understand that they take sometimes significant risks, and they want a number gleaned from risk models to quantify that risk and guide their decisions. However, in certain instances, the tantalizingly close potential for large rewards can lead executives to ignore the results of those models—or at least take them for granted by not fully grasping what the number really indicates.3

Similarly, business leaders today are confronted with the large demand for new technologies and the potentially huge returns from investing in these technologies. These leaders also understand, though, that by continuing to extend complex information systems and networks, they are often significantly increasing risk to the enterprise. This is leading to growing interest in developing risk models that quantify cyber risk and support the development and execution of cyber risk strategies and security programs.

What types of models are being used, and in what context? By relying too heavily on these models and ignoring other cyber risk indicators, could business leaders face a danger of being blindsided by a catastrophic cyber event?

Certainly, risk models are important tools for framing and understanding risk elements. But as they work to quantify cyber risk, enterprise leaders and chief information security officers can benefit from understanding financial institutions’ risk management experience. Organizations should be cautious of relying solely on risk models and, instead, build strong governance processes surrounding these models. Without strong processes, leaders could become overconfident of their cyber risk posture—and oblivious to warning signs—leading to potential financial, operational, and reputational loss.

The risk of a black swan event

Various types of risk can influence the value and performance of financial investments, generally categorized as credit, liquidity, market, and operational risk. Value at risk, or VaR, is prominent among the modeling techniques financial institutions have used for decades to calculate the market risk within their investment portfolios. VaR is “a statistical technique [for] measur[ing] and quantify[ing] the level of financial risk within a firm or investment portfolio over a specific time frame.”4

In its most common form, VaR measures portfolio risks over short periods of time, assuming “normal” market conditions. An investment manager whose portfolio shows a VaR of $100 million one week, for example, has a 99 percent chance of not losing more than that amount from the portfolio the following week.5 However, VaR typically cannot describe the 1 percent of the time that $100 million will be the least that can be lost. This limitation means that VaR cannot measure the risk of a “black swan event”—a highly improbable occurrence with outsized impact—such as cascading home foreclosures and subprime mortgage losses.6

Key takeaway: Risk models like VaR serve a vital function, aggregating a variety of inputs and providing an indicator for decision makers to factor into their reasoning. An inherent shortcoming, however, is that the output is only as good as the input, and neither necessarily quantifies all risks.

Growing cyber concerns and the drive to quantify cyber risk

Here, it’s important to understand public and private sector concerns about cyber black swan events and the emerging role of a “cyber VaR” model in quantifying cyber risk.

Officials across the globe are increasingly concerned about the risks that cyberthreats pose worldwide, some warning of the potential for cyber events to grow into systemic calamities. Greg Medcraft, former chairman of the board of the International Organization of Securities Commissions, for example, has predicted that “the next big financial shock—or ‘black swan event’—will come from cyberspace, following a succession of attacks on financial players.”7

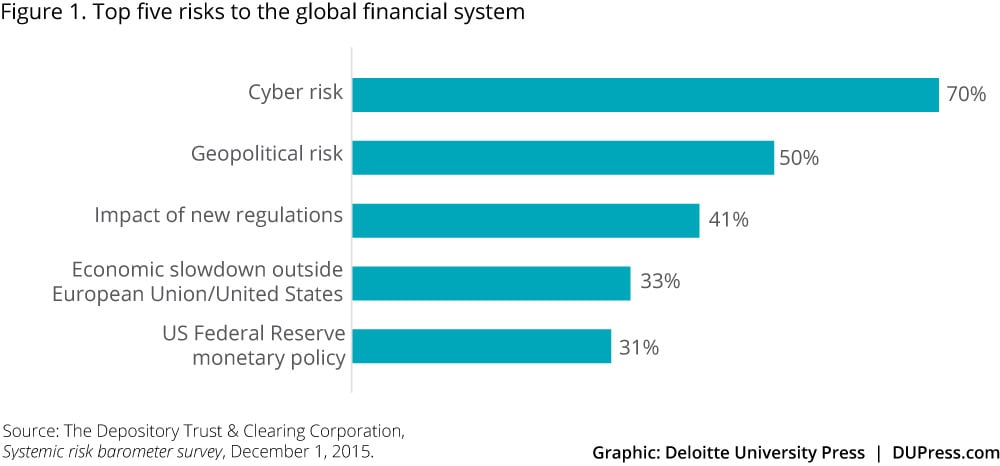

Corporate risk managers also worry about a cyber black swan event. In a 2015 study by the Depository Trust & Clearing Corporation (DTCC), 61 percent of financial services risk managers surveyed believed the probability of a high-impact event in the global financial system had increased in the previous six months. As in the previous DTCC survey conducted in Q1 2015, cyber risk remained the No. 1 concern globally, with 70 percent of all respondents citing it as a top-five risk (figure 1). Respondents cited the frequency of attacks and the ability to manage them as top concerns.8

Certainly, cyberthreats are not exclusive to financial services and the global financial system. The potential for cyber black swan events in other sectors is a stark reality:

- Utilities industry. A December 2015 cyberattack that shut down part of Ukraine’s power grid prompted the Obama administration to issue a warning to US power companies, water suppliers, and transportation networks about the risk of similar attacks.9

- Health care. After persistent 2015 and 2016 cyberattacks on health care facilities and hospitals in North America, the US Department of Homeland Security, collaborating with the Canadian Cyber Incident Response Centre, issued a warning to health care organizations about ransomware and other variants that can cause “temporary or permanent loss of sensitive or proprietary information, disruption to regular operations, financial losses,” and reputational harm.10

- Oil and gas. Three out of four oil and gas, energy, and utility IT professionals surveyed in late 2015 had experienced an increase in successful cyberattacks, and most of those (68 percent) said the rate of successful cyberattacks had increased 20 percent in just the last month.11

- Government. A massive breach of the US Office of Personnel Management in 2014–2015 resulted in the theft of sensitive information, including the Social Security numbers of 21.5 million individuals from employee and contractor background investigation databases.12

So what actions are authorities and other stakeholders taking on a broad scale to respond to the growing systemic nature of cyberthreats?

One major initiative is the World Economic Forum’s multi-stakeholder Partnering for Cyber Resilience initiative, launched at its 2011 annual meeting in Davos, Switzerland. Involving more than 100 experts, businesses, and policy leaders, the project’s goal is to “address global systemic risks arising from the growing digital connectivity of people, processes, and infrastructure.”13

After first focusing on raising awareness of cyber resilience among senior-level leaders, in 2014 and 2015, the members shifted their attention to the need for “a shared cyber resilience assurance benchmark across industries and domains.”14 To create a successful risk quantification model, they began by listing various types of models used within their organizations. The Monte Carlo method was predominant, but elements of other models were also deemed important, including:

- Behavioral modeling

- Parametric modeling

- Baseline protection

- The Delphi method

- Certifications

The initiative’s exploration led to the framing of a cyber VaR concept “based on the notion of value at risk, widely used in the financial services industry.”15 Using a probabilistic approach, a cyber VaR model estimates the likely loss an organization might experience from cyberattacks over a given period—that is, “Given a successful cyberattack, a company will lose not more than X amount of money over a period of time with 95 percent accuracy.”16

In explaining its decision to develop a measure based on financial VaR, the Partnering for Cyber Resilience initiative noted, “The financial service[s] industry has used sophisticated quantitative modeling for the past three decades and has a great deal of experience in achieving accurate and reliable risk quantification estimates. To quantify cyber resilience, stakeholders should learn from and adopt such approaches in order to increase awareness and reliability of cyberthreat measurements.”17

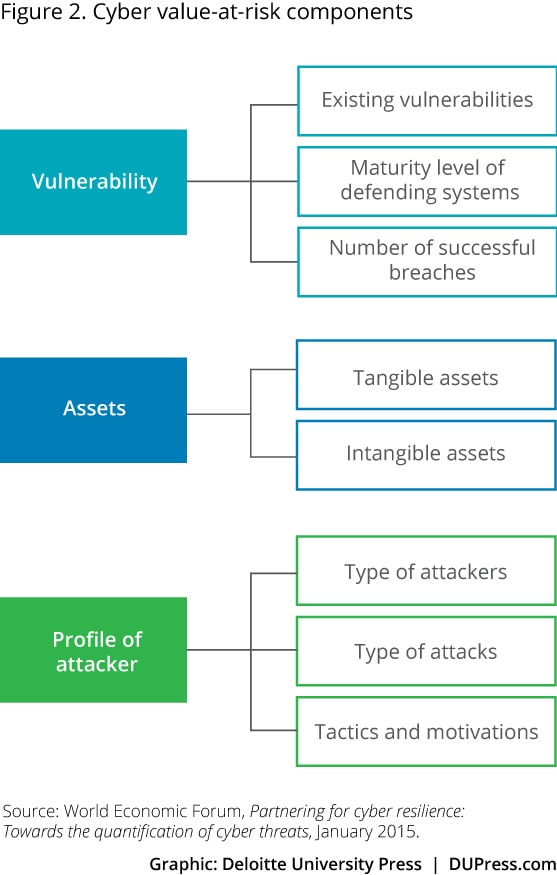

The World Economic Forum stakeholders did not attempt to devise one specific cyber VaR model; instead, they suggested specific properties of a cyber VaR framework that industries and individual companies should incorporate into their own models. In this way, each organization can assess the components to determine applicability and impact to their own environment. That cyber VaR framework comprises these broad components (figure 2):

- Vulnerability of existing assets and systems and the maturity of defending systems

- Assets under threat, both tangible and intangible

- Profile of attackers, including types (for example, state-sponsored vs. amateur and level of sophistication) and their tactics and motivations

The cyber VaR components, some of which can represent random variables (variables subject to “change due to chance,” such as frequency of attacks, general security trends, and the maturity of an organization’s security systems), are put into a stochastic model. The model is a statistical tool to estimate probability distribution incorporating one or more random variables over a period of time. Analysis of the dependencies between components can contribute to various models for estimating risk exposure.

Quantitative risk models represent an evolution in the management of cyber risk. However, when considering the cybersecurity realm, the use of risk models in general—and VaR specifically—invites an important question: Could a cyber VaR model pose a fundamental risk to organizations that choose to adopt it?

Key takeaway: The incredible complexity and ongoing expansion of the cyberthreat landscape are driving organizational initiatives to quantify cyber risk, much as financial institutions sought ways to quantify market risk in the burgeoning labyrinth of securities derivatives of the 1990s and early 2000s.

The importance of using risk models—judiciously

The answer to the question posed above hinges largely on the context within which an organization employs cyber VaR. We’ll next explore how three very different approaches to using the VaR model yielded three diverse outcomes.

VaR’s limitations were well known as far back as the 1990s, perhaps most famously in the 1998 fall of Long Term Capital Management (LTCM). LTCM’s demise

Exposed the limitations of VaR modeling and inadequacies of historical probabilities in predicting the future. Because Russia defaulted on its domestic (rather than foreign) debt, something that had never occurred before, LTCM’s VaR models assigned a probability of zero and incorrectly calculated the losses of this event. The miscalculation threw LTCM into a liquidity crisis, eventually leading to a bailout by a private consortium of banks and financial institutions.18

Despite this very public example of VaR’s limitations, the model continued to be popular and widely used in the financial services industry. Different varieties of VaR were used by different firms, but, typically, a firm’s stated risk approach involved daily VaR calculation at a 95 percent confidence level, as shown in figure 3.

The consequences of a laissez-faire attitude toward VaR outputs is illustrated by the experiences of a company we’ll call Firm X, which had taken on an aggressive investment posture with the endorsement of its board of directors. According to emails from the risk management team, the firm’s senior management disregarded its risk managers and failed to follow policies around its risk limits. Furthermore, management excluded certain risky principal investments from its stress tests without informing the board of directors, and it lacked a regular, systematic means of analyzing the amount of catastrophic loss that the firm could suffer from increasingly large, illiquid investments. And, in fact, Firm X eventually did suffer catastrophic losses that led to its bankruptcy.

Lessons learned in the years since Firm X’s demise suggest the value of a different approach to corporate governance and risk management. This is illustrated by the story of another large financial firm, which we’ll call Firm Y.

It starts when Firm Y leaders notice that the company’s profit and loss figures reveal that its mortgage business has lost money for 10 consecutive days. Watching these trends closely, senior executives and risk managers decide to delve deeper to find out why this is happening. They examine the data thoroughly, and then choose to collaboratively examine the firm’s trading positions.

With a strong financial governance process in place, Firm Y uses a variety of quantitative risk measures—ensuring that none outweighs its profit and loss statements. Executives are careful to not rely solely on any one calculation or input source. By weighing all available evidence regularly and, using their professional judgment, Firm Y’s leaders are likely to avert disaster by realizing they need to shed and hedge their mortgage-backed security positions.

How do the experiences of LTCM, Firm X, and Firm Y relate to quantification of cyber risk? One report points to shortcomings in board oversight of cybersecurity, concluding that boards are not paying close enough attention to security-related issues such as budgets, assessments, policies, roles and responsibilities, breaches, and even information technology risks.19

In describing the need for risk frameworks that address concerns about excessive reliance on risk models, José Manuel González-Páramo, an executive board member of a large global bank, said, “There has historically been an overreliance and mechanical use of models and external opinions. . . . Those models, measures, and opinions are still valid tools, but need to be used in a correct manner, and need to be complemented by other tools and, more generally, by expert judgment.”20

One outcome of the Partnering for Cyber Resilience initiative is for participants to collaborate on devising an approach to “near-real-time information sharing [that] can address data availability challenges and supply enough data to build statistical models.”

Viewed in this context, the effective use of cyber VaR and other models to quantify cyber risk involves challenges similar to those financial institutions often face, among them the perennial issue of data quality. Some fundamental data used in cyber risk models, such as frequency of attacks, can be difficult to acquire when the majority of cyber incidents go unreported.21Moreover, the extensive data sets needed to model the probability of cyberattacks are still being developed. One outcome of the Partnering for Cyber Resilience initiative is for participants to collaborate on devising an approach to “near-real-time information sharing [that] can address data availability challenges and supply enough data to build statistical models.”22 This undertaking, along with individual companies’ efforts to better understand and characterize their internal data—for example, quantifying the relationship between enterprise assets and the company’s revenue and profit picture—are vital to the efficacy of cyber VaR and other cyber risk quantification models.

Other challenges, more organizational in nature, include persistence of operational silos, lack of communication, and inadequate governance. Among these, inadequate governance, along with overdependence on the risk models, has perhaps the greatest potential to foster a false sense of security.

Key takeaway: Growing cyber risks are compelling organizations to consider the use of risk models. The valuable information that risk models such as VaR can provide should be weighted along with other inputs. To carefully structure and manage cyber risk activities, organizations must prevent any one input from having outsized influence.

Governing the use of models in cyber risk management

Among the desirable attributes of a cyber VaR model highlighted by the Partnering for Cyber Resilience initiative is the model’s potential to serve as an effective risk measurement tool for executives and decision makers. One key element of fulfilling this role is that the model be viewed through the lens provided by a company’s existing enterprise risk management framework, such as the Internal Control—Integrated Framework or the Enterprise Risk Management Integrated Framework developed by the Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission.23 The components of internal control typically include, at a high level:

- The control environment overseen by the board of directors

- A risk assessment taking into account operations, reporting, and compliance objectives and the potential impact of cyber risk on them

- Control activities aimed specifically at managing cyber risks within the organization’s risk tolerance

- Management of information and communications relating to cyber risk generally and specific cyber risk events

- Monitoring activities that evaluate the effectiveness of internal controls that address cyber risks24

Viewing cyber VaR through this lens provides the board of directors and senior executives with an established, effective approach to communicating business objectives, their definition of critical information systems, and their appetite for associated cyber risks. In turn, that guidance from the board and senior management sets the tone—and establishes expectations—for rigorous cyber risk analysis across the enterprise.

By embedding cyber VaR within the broader enterprise risk management framework, Partnering for Cyber Resilience suggests, a company’s cybersecurity program can be reinforced with “continuous and proactive engagement from senior management.”25 In a 2015 speech, Cyril Roux, deputy governor (financial regulation) of the Central Bank of Ireland, expanded on the importance of management engagement when he outlined the bank’s expectations of financial firms with respect to cybersecurity. The themes Roux articulated provide helpful guidance for businesses in any industry seeking to strengthen their ability to detect, prevent, and recover from cyber intrusions. Among them:

- The board should have a good understanding of the main risks. This will help board members effectively challenge senior management on the security strategy.

- Perform risk assessments and intrusion tests. Organizations should perform cybersecurity risk assessments on a regular basis.

- Prepare for successful attacks. Organizations build resilience through distributed architecture, multiple lines of defense, and readiness to mitigate impact on customers.

- Manage vendor risk. Organizations should perform cybersecurity due diligence on prospective and existing outsourced service providers, and incorporate cybersecurity and data protection provisions into outsourcing agreements.

- Gather information and follow leading practices. Organizations should follow and apply industry standards to their cybersecurity risk-management frameworks as appropriate for the scale and nature of their business and participate in industry information-sharing groups.

- Educate staff. Organizations should address the “human factor” through regular security awareness training for all staff.

- Put robust IT policies, procedures, and technical controls in place. These include incident reporting and response plans, recovery and business continuity plans, patch management, and employee access rights.

- Consider buying cyber insurance. Organizations may consider evaluating the possibility of using cyber insurance as a partial risk-mitigation strategy.26

The importance of the first theme in the list above cannot be overstated. The board and senior management should challenge one another to critically analyze and weigh all risk inputs. Key elements of board risk oversight include:

- Communication between the board of directors and members of senior management

- Communication among the board of directors, board committees, and board advisors

- Efficient coordination through a straightforward risk management process uncluttered by too many participants

- Expecting the unexpected through activities such as discussion and analysis of possible risk scenarios with the management team27

The last of these four items points to an opportunity for boards to actively engage their management teams in reviews of various risk scenarios. This approach can help boards understand whether the management teams are taking effective action in their risk management processes and can identify areas where improvement is needed.

Some boards may assign responsibility for risk management oversight to their audit committees. They may also want to consider forming a stand-alone cyber risk oversight committee that engages regularly and directly with executives across the organization who are tasked with cyber risk management.

Education of boards, and of senior executives, about cyber risks is central to strengthening directors’ roles in addressing these threats. Tools such as The cyber-risk oversight handbook, published by the National Association of Corporate Directors (NACD),28 and guidance from sources such as Managing cyber risk: Are companies safeguarding their assets?, published by NYSE Governance Services,29can be useful in such efforts.

Key takeaway: Boards and senior management have an increasing responsibility to monitor their organization’s cybersecurity posture, provide oversight of cybersecurity strategy execution, and be prepared to respond to investor, analyst, and regulator questions about actions taken around cybersecurity. Cyber VaR and other risk inputs play a valuable role in fulfilling that responsibility.

Learning from the past to prepare for the future

Business leaders increasingly recognize that quantifying cyber risk is essential to understanding its potential consequences and allocating resources to protect digital assets. As we have seen, whether dealing with financial or cyber risks, risk models can play an important role in addressing threats. Models aid in identifying and evaluating data patterns and trends, a key dimension of the quantification process, along with sound governance processes, available risk data, and skilled cybersecurity and analytics specialists.

At the same time, relying too heavily on the models while ignoring or subordinating other considerations, can open the door to disastrous consequences. Instead, it is important to develop well-defined cyber risk models that align with the nature of a given business.30 Companies can translate the outputs from these risk models into simple-to-understand concepts that can be used to initiate frank risk-reward conversations across various levels of management and the board. The concepts can help increase these stakeholders’ understanding of both the dangers and potential opportunities associated with cyber-related risks in the context of business innovation and growth. In conveying these concepts, it is important to avoid creating a false sense of precision about the models, especially given the lack of empirical data available for certain model inputs.

By keeping the role and importance of models in context when applying them to a cyberthreat environment, businesses and regulatory authorities can enhance their risk intelligence and improve their stewardship in the interest of investors and customers. DR