Canada Dark economic clouds bring rougher seas

The Canadian economy enters a period of slower economic growth.

The year 2019 is expected to be a year of economic transition, both internationally and in Canada. In our last forecast “Singing the late cycle blues,”1 our key theme was that the North American economy was in the late stages of a business cycle. Economic and financial developments since then have only reinforced that view.

Learn More

Subscribe to receive related content

View past outlooks for Canada

Explore the Economics: Americas Collection

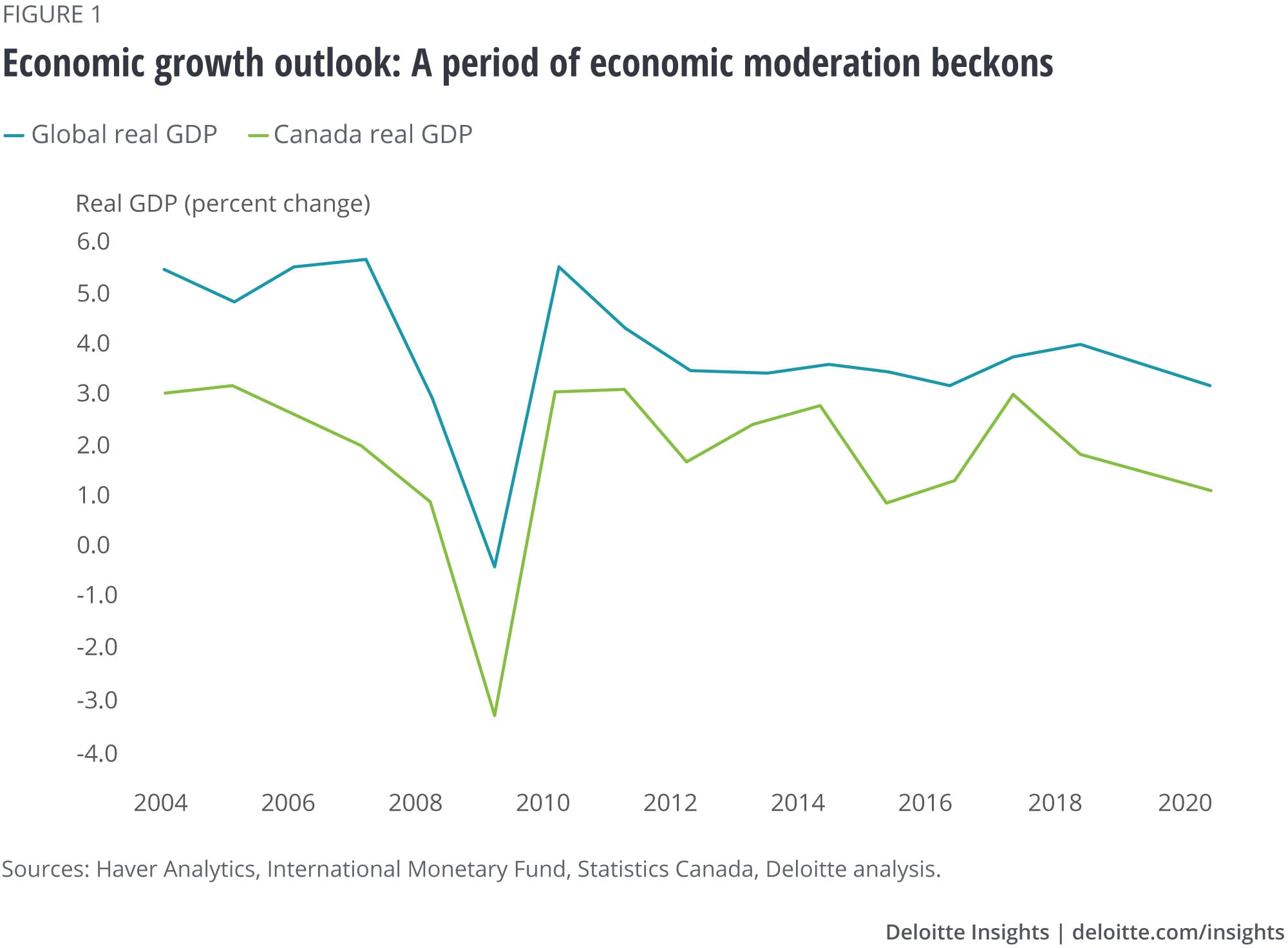

Global economic growth appears to have peaked in 2018, and the base case forecast is for growth to moderate in 2019 and 2020 (figure 1). The US economy may continue to outperform other advanced economies in terms of the absolute pace of expansion, but it is expected to experience the greatest degree of slowdown among them over the next two years. Canadian economic growth possibly will gear down from close to 2.0 percent in 2018 toward 1.6 percent in 2019.

One key development since our last forecast has been an oil price correction. Although we forecast that crude oil prices will rise from their recent lows, a sustained lower level of prices and production will have a negative impact on Canadian economic growth in 2019.

The economic cycle risks increase in 2020, as fiscal drag is expected to weigh significantly on US economic growth, negatively impacting integrated North American supply chains. Consequently, Canadian economic growth is projected to drop to 1.3 percent in 2020.

Yet another crude oil shock

Before delving into the details of the macro outlook, it is important to evaluate how the correction in oil prices in late 2018, and the Alberta government’s policy response, will impact Canada’s economic prospects. At the time of our October forecast report, West Texas Intermediate (WTI) crude oil was priced at US$76 per barrel. Global oil inventories were broadly in balance, but Alberta was receiving a discount of around US$17 on its Western Canada Select (WCS) crude oil. Then, financial market sentiment soured. Equities corrected and WTI crude oil prices plunged, dropping toward US$45 per barrel, reflecting fears of slowing global economic growth that could reduce oil demand and create an inventory buildup. There was also a feeling that oil sanctions against Iran had not lowered the supply by as much as expected. The drop in WTI was bad enough, but the price for WCS fell further, widening the spread between the two greatly—at one point during November, Alberta was receiving less than US$14 per barrel for oil priced in WCS.

The persistent gap in the price between WTI and WCS is partly due to the fact Alberta has only one customer for its crude, the United States. Furthermore, the shale oil revolution in the United States has led to a dramatic increase in oil production there, weakening demand for Alberta oil exports and, therefore, the price it receives. Another factor is Canada’s inability to build pipelines, constraining Alberta’s ability to move its crude oil, thereby causing excess supply. Moreover, the province cannot tap rising overseas demand because it is landlocked.

These factors have been weighing on WCS prices for years, but the spread between WCS and WTI prices was worsened by negative financial market sentiment about slower global growth prospects and temporary refinery shutdowns.

The oil price correction, similar to the equity correction, in December is likely overblown. Global economic growth may have peaked in 2018, but it’s still likely to be healthy in 2019. Moreover, the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (commonly referred to as OPEC) announced a production cut in December, and further production reductions are likely if prices don’t recover. Consequently, our forecast is for WTI to rise toward US$58 per barrel in 2019. The following year could see weaker global demand growth offsetting supply reductions and limiting the impact on prices. While WTI crude oil prices are lower than in our last forecast, the Alberta government’s response to the price decline is equally key for the province’s economic outlook.

Faced with no good options, the Alberta government responded in a nontraditional way by announcing on December 2 a curtailment of crude oil production.2 The objective is to reduce production by 9.0 percent (325,000 barrels per day relative to peak production), with the reduced supply intended to bolster local oil prices. The curtailment will start in January 2019, but ease over time.

The market reaction has been significant, with the WTI-WCS spread narrowing dramatically. This will improve the price received by many Alberta producers and may limit the downside to investment activity and employment in the oil patch. However, the production reduction will lower the province’s real GDP, likely reducing Alberta’s economic growth by half to one full percentage point. This impact on Alberta will be felt in overall Canadian real GDP, lowering growth by as much as 0.2 percentage points in 2019.

Canada’s economic moderation

Turning to recent economic developments, the Canadian economy shifted down a gear in the third quarter, but the pace of expansion remained healthy and above the country’s long-term sustainable rate. Real GDP growth dropped from 2.9 percent (annualized) in the second quarter to 2.0 percent (annualized) in the third quarter, exactly in line with our projection in the last Deloitte Canadian forecast publication. That said, the details of the latest national accounts reveal weaker results than what the headline of solid economic growth suggested.

Consumer and real estate providing less support

Consumers and real estate are contributing less. A key theme from our last forecast was that heavily indebted consumers with little pent-up demand for big-ticket purchases could not continue being the engine of growth. Nor could real estate add much to the economic expansion. Both of these trends were evident in the recent data. Household expenditure growth fell to a modest 1.2 percent in the third quarter. Auto sales were a particular source of weakness, but the moderation in growth of outlays was broadly felt across most other categories of consumer spending as well.

Consumer spending growth should be a bit stronger in the next couple of quarters, but we expect expenditure to average 1.5 percent growth in 2019 and 1.4 percent in 2020. This will reflect more modest employment growth, compensation gains in line with or slightly above the rate of inflation, and relatively flat real estate markets that will dampen big-ticket household purchases, like furniture and appliances.

The implementation of a new mortgage stress test—requiring buyers qualify for mortgages as if interest rates were 2.0 percentage points higher than the transaction rate—at the start of 2018 had the effect of significantly dampening the resale housing market activity during the year. Some buyers were pushed out of the market, particularly in the least affordable cities. The far greater impact was a reduction in the size of mortgage being qualified, which lowered the price point for transactions and reduced the average price of homes being sold. Home sales declined in most markets, but so too did listings. As a result, the sales-to-listing ratios declined in Canada’s major markets and this limited the negative impact on resale home prices. The fallout of the mortgage income stress test has waned over time, but resale activity has also felt a headwind from rising interest rates. The weaker real estate demand has also been felt in new home construction. Looking ahead, national average home sales and prices are expected to be relatively flat as are the pace of new home construction, reflecting modestly higher borrowing costs, limited household willingness to take on significantly greater debt, and weaker economic conditions.

Business investment disappointed in third quarter, but should firm up

Given Canadian households’ high indebtedness, the economy has long been in need for business investment and exports to play a larger role as growth drivers. There were positive signs in late 2017 and early 2018. Regrettably, the trend stalled, with the pace of business investment slowing the second quarter of 2018 and then declining in the latest data. Investment in nonresidential structures fell 5.2 percent (annualized) while investment in machinery and equipment fell 9.8 percent (annualized) in the third quarter. While the outturn was disappointing, there are reasons to believe the contraction is temporary.

- The large drop in machinery and equipment in the third quarter was partially due to a 51.0 percent plunge in aircraft and transportation equipment, a volatile component that is unlikely to have a repeat performance. It may have been that the aircraft purchases were simply delayed.

- The latest data doesn’t show the business response to the new US-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) free trade deal. Although it still has to be ratified—implying that political risk is still present—implementation is highly probable. With the uncertainty on trade policy lifted, one would expect some delayed investment to occur in the coming quarters.

- Businesses need to invest to meet future demand. Business investment in recent years has been weak, particularly if new outlay in machinery and equipment in Canada’s capital stock is assessed after removing depreciation. Also, firms are operating at high levels of capacity.

- In its fall 2018 economic and fiscal update, the government of Canada announced that it was allowing firms to write off investments at an accelerated rate. This lowered the marginal effective tax rate on investment, making new investments less expensive.

Accordingly, we expect stronger business investment to start making a greater contribution to economic growth. However, the rate of investment growth will likely be constrained by meager investment in the energy patch and a cyclical slowdown in the North American economy in 2020.

Exports supported by foreign demand, weak Canadian dollar

Net international trade contributed to Canadian economic growth in the third quarter, but disappointingly. Imports plunged almost 8.0 percent (annualized) in the quarter, reflecting the weakness in consumer spending and, more importantly, the decline in business investment. Exports only rose a modest 0.9 percent (annualized).

Trade performance should improve in the fourth quarter of 2018 and in 2019. Although global growth is moderating, it should remain healthy and support export growth. The Alberta government’s measure to limit oil production in the province could constrain shipments, but nonenergy exports should be healthy. Meanwhile, import growth will likely return as Canadian companies import machinery and equipment, and consumers keep their wallets open, albeit spending at a lower rate.

The Canadian dollar should also help net trade—the loonie lifted to 78 US cents in October amid news of the USMCA deal, but weakened as oil prices fell and markets grew worried about global growth prospects. At the end of December, the loonie stood at 73.30 US cents, helping export competitiveness and making imports more expensive. The forecast for the Canadian dollar is tied to changes in commodity prices and differential in short-term interest rates between Canada and the United States. With respect to the former, we expect commodity prices to rise in early 2019, but face headwinds from slower global growth in 2020. Meanwhile, little change is expected between the spread on US and Canadian interest rates. We see the currency fluctuating in a range of 73–76 US cents over the forecast horizon.

In terms of risks, if the global economy disappoints and stumbles, the Canadian dollar will be weaker than in the base case forecast. Conversely, if the global risks do not manifest, the US dollar looks overvalued relative to most other currencies, which could provide some upside to the loonie.

Canadian regional prospects

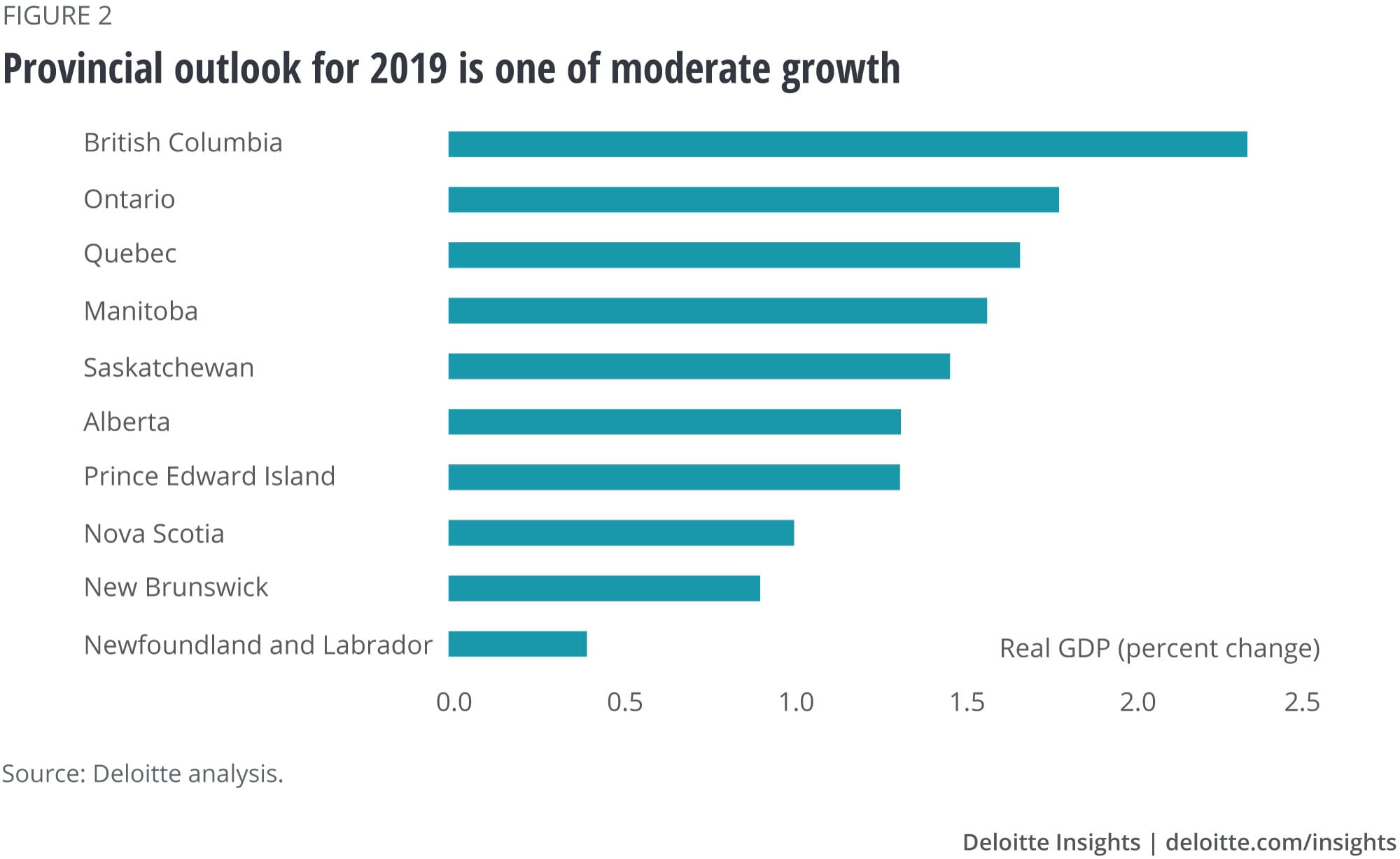

Putting together all the pieces of the Canadian outlook, the emerging picture is one of a national economy that will experience more moderate economic growth of 1.6 percent in 2019, followed by perhaps a more substantial slowdown to 1.3 percent growth in 2020. Regional performances, however, will vary in the coming year (figure 2).

In Alberta, lower oil prices and production curtailment measures are likely to drag provincial economic growth from 2.3 percent in 2018 to around 1.3 percent in 2019. This is a particularly regrettable outcome, given that the province experienced a deep recession in 2015 and 2016.

The Atlantic provinces will likely post slower rates of expansion than Alberta, largely because of aging demographics constraining sustainable growth in the region to an annual pace of around 1.0 percent. The projections may therefore seem low, but they represent a respectable performance in the coming year.

Quebec’s pace of expansion will be close to that of the national rate, but this is an above-average performance for the province. It suggests continued challenges for businesses from tight labor markets.

Growth in Ontario will also be near the national average, which is an inevitable outcome since it’s the largest province in the federation. A key development in the last quarter, however, was the announcement by General Motors that it does not have a viable business case for production at its Oshawa assembly plant past the end of this year because of rapid changes in the North American car market, the cancellation of Oshawa products, and persistent low utilization at the plant.3 If production is shut down, the effects will ripple out to the auto sector more broadly. Ontario has been facing challenges in attracting new investment in manufacturing, which raises a question about the extent to which traditional manufacturing can be a major driver for Ontario’s economic growth in the future. Ontario is particularly vulnerable to an economic slowdown in late 2019 and 2020 due to its US trade reliance.

Manitoba will grow a bit below, yet close to, the national average. This reflects the diversified nature of its economy, which means it will be shaped by general macro trends.

Saskatchewan could feel the headwind of lower energy prices, but agriculture could provide a push to post a gain of 1.5 percent in 2019.

British Columbia should top the provincial leaderboard, with growth of 2.3 percent in 2019. While US trade exposure will be a negative for the 2020 outlook, the westernmost province will likely receive a boost over the forecast period from the construction of a C$40 billion liquefied natural gas pipeline and processing plant.

Conclusion: Downside risks are mounting, but a slowdown is most likely

With the arrival of a new year, it’s natural to wonder what’s in store. We expect 2019 to be a year of economic moderation in Canada.

Storm clouds are gathering on the horizon in the form of key downside risks. Further US protectionism and international retaliation, a potentially messy UK exit from the European Union, and increased market volatility could contribute to weaker global growth, lower commodity prices, and detrimental economic and financial consequences around the world over the next couple of years.

It is also important to be mindful of where we are in the business cycle. There is empirical evidence that the typical economic recovery and expansion cycle is eight to 10 years long. It has now been a decade since the last downturn, so the current business cycle is long in the tooth. This is likely part of the reason that financial market sentiment became negative in late 2018. A downturn is not in the base case Deloitte economic forecast, but we are monitoring the risks closely.

While the downside risks have risen, we advise Canadian businesses to not overreact. They should not paralyze or delay decision-making in the face of a riskier economic environment; they should rather continue building for the future—making key investments, developing their talent, and growing their businesses. At this stage, firms should be bracing for slower economic growth, but also considering how they’ll handle the next business cycle when it emerges.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.

Explore more economics content

-

Canada: Economy on good footing, for now Article6 years ago

-

United States Economic Forecast Q1 2025 Article1 month ago

-

How do Americans spend their time? Infographic6 years ago

-

Eurozone economic outlook, September 2024 Article7 months ago