Canada: Economic growth gearing down, but to a sustainable pace

28 November 2018

Consumption-led growth in Canada is coming to an end, cooling economic growth to a sustainable pace, but headwinds loom.

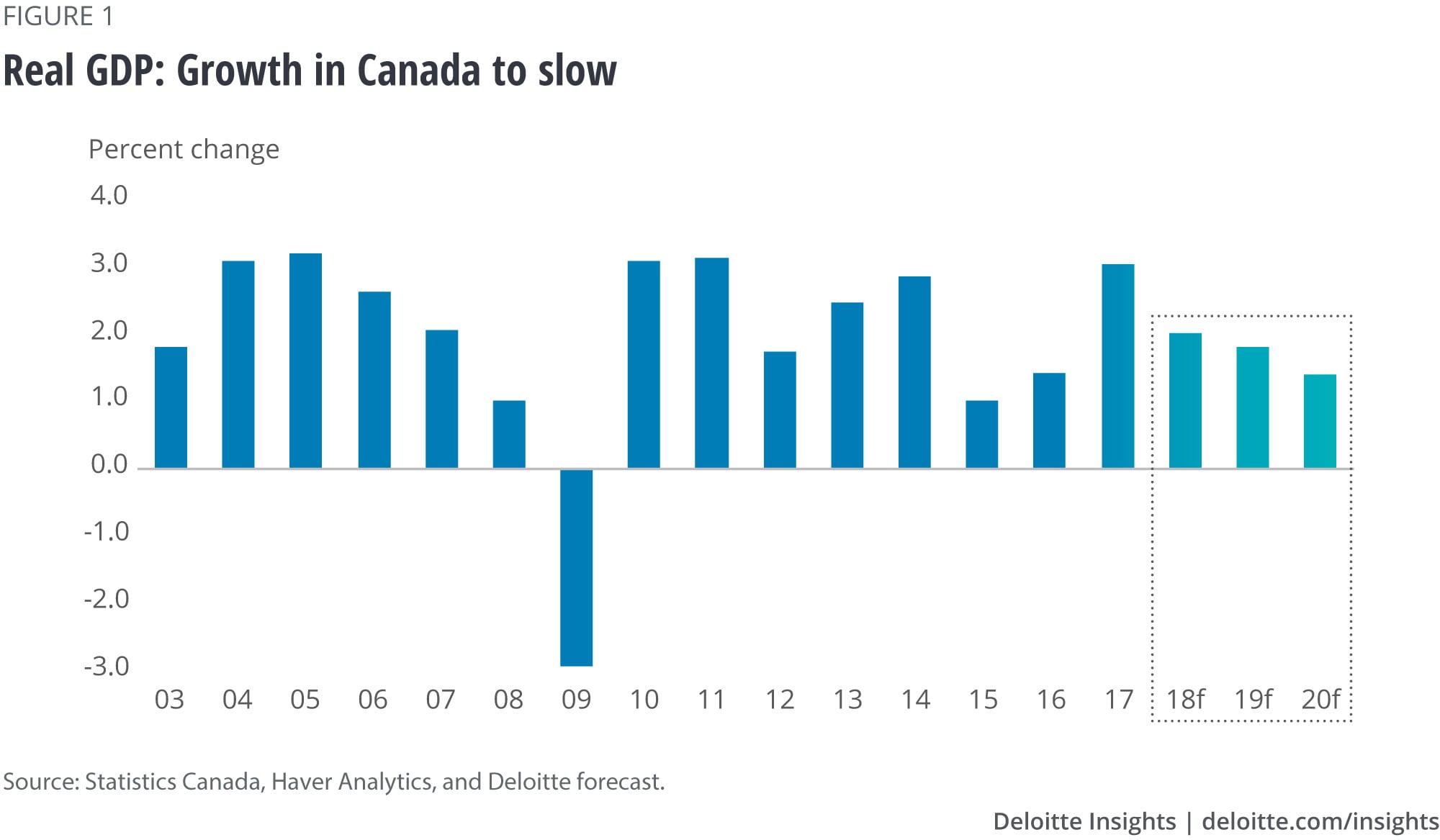

Economic growth in Canada is shifting down a gear. This is a healthy occurrence, given that the economy has little domestic slack, as evidenced by the unemployment rate being at a nearly four-decade low and very high levels of capacity utilization. Softening economic growth will also reflect a shift in the main drivers of expansion. Domestic demand growth is poised to diminish because consumers and real estate can no longer drive growth as they have in the past. This means that exports and business investment will be more important contributors to economic growth. The tentative free trade deal between the United States, Mexico, and Canada, called the USMCA, lifts a key cloud of uncertainty that posed a downside risk to the outlook and it should help boost exports and investment. However, the transition in economic drivers is unlikely to go smoothly. With global and US economic growth likely peaking this year, weaker demand growth and potentially lower commodity prices are expected to be a headwind on exports over the next few years. Moreover, businesses are expected to remain cautious in their capital spending. Accordingly, after growing a robust 3.0 percent in 2017, the pace of economic growth in Canada is projected to slow to slightly below 2.0 percent in 2019 and drop to 1.4 percent in 2020.

Consumers to continue spending, but at a moderate pace

The economic expansion seen over the past decade in Canada has been a result of robust consumer spending. Strong job creation, declining unemployment, rising personal income gains, low interest rates, and strong real estate markets have helped to keep consumer wallets open.

While the consumer narrative remains positive in 2018, there are headwinds that will likely constrain spending growth. First, consumers are likely to be reluctant to ramp up their debt levels further. Debt as a share of real personal disposable income has climbed to lofty levels, and the share of after-tax income going to service debt is also elevated. Looking forward, households are expected to constrain their debt growth as rising interest rates lift debt-servicing costs. The Federal Reserve will be raising interest rates, lifting US bond yields and, thereby, Canadian bond yields; this is likely to boost fixed mortgage rates in Canada. Meanwhile, we expect the Bank of Canada to raise the overnight rate by 75 basis points in 2019, which will raise variable mortgage rates.

Second, real estate markets are relatively flat. The imposition of income stress tests on all mortgages originated at federally regulated institutions led to a pullback in Canadian real estate market activity in 2018, particularly in the largest and most expensive Canadian cities. In the past, effects of regulatory changes have influenced markets for six to nine months, before they subsided. This appears to be happening in the Greater Toronto Area. New headwinds on real estate could come from slowing job creation and gradually rising interest rates, possibly causing weaker new home construction and relatively flat existing home sales in 2019. These trends will temper consumer spending on housing-related items, such as furniture and appliances.

That being said, we project personal consumption growth to increase 2.2 percent this year, but wane to 1.8 percent in 2019 and to 1.4 percent in 2020 (figure). This will weigh on aggregate economic growth because consumption is more than half of the economy, as measured by gross domestic product.

Investment may disappoint

Investment in nonresidential structures experienced a strong increase in the first quarter of 2018, but lost momentum in the second quarter. Firms are reporting that they are running at high capacity, so some additional investment in nonresidential structures should be in the offing. However, businesses are being cautious in their investment plans, and slower economic growth over the course of 2019 and 2020 will temper investment in nonresidential projects.

After two very strong quarters of growth, business investment in machinery and equipment (M&E) stalled in the second quarter of 2018. However, capacity pressures should encourage businesses to invest in M&E. Canadian businesses tend to invest less in capital per worker than international peers, and business cautiousness as well as weaker growth prospects in North America may temper the pace of expansion in capital spending. M&E investment should advance by roughly 8.0 percent this year, due to a remarkably strong first quarter, but slow to around 3.2 percent growth in 2019 and further to 2.4 percent in 2020.

Government investment declined in the second quarter of 2018 but was still up 5.4 percent year over year. The federal government committed to large-scale funding of infrastructure in its last two budgets, and government investment rose 5.1 percent and 3.8 percent in 2016 and 2017, respectively. These are solid increases, but still represent a gradual rollout of the planned infrastructure investment. The delays are a result of the time spent in planning, getting approvals, and collaborating with provinces on many projects. The federal government is still committing the full amount of funds, and provinces need to upgrade and expand their infrastructure, so further gains in this category are expected over the forecast period.

Exports to be a key contributor to economic growth

Exports delivered an impressive increase of more than 12 percent (annualized) in the second quarter. Looking forward, Canadian exports will be supported by rising foreign demand, owing to a robust US economy and increasing global demand for commodities, and a Canadian dollar below 80 US cents. Nonetheless, the pace of export growth will be constrained by the loss of market share in many key international markets in recent years. Exports are particularly vulnerable in 2020, when the US economy is likely to experience significantly slower growth. Canadian exports are expected to grow at 3.0 percent in 2018, slowing to 2.8 percent in 2019, and to 1.7 percent in 2020.

Inflation to remain in abeyance

Inflation, as measured by the year-over-year change in the Consumer Price Index, stood at 3.0 percent in August, which is at the top of the Bank of Canada’s target range of 1–3 percent. The bank views a number of temporary factors as pushing up headline inflation. Meanwhile, core measures of inflation, excluding some of the volatile components, are sitting very close to the bank’s 2.0 percent mid-point target. In September, inflation dropped to 2.2 percent, and it is expected to hover around the 2.0 percent mark over the forecast period.

Labor markets not as robust as last year

Job creation in Canada has been strong but is clearly decelerating. After a job boom in 2017, the monthly pattern in 2018 has been very choppy and job creation has been weak. The prior robust pace of employment creation pushed the unemployment rate down to a 40-year low of 5.8 percent in the first half of the year. Typically, such a low rate of unemployment would create concerns about a possible rise in inflation. But the Bank of Canada is not unduly worried, and there is good reason.

First, demographics are distorting the historical comparison as baby boomers’ participation in the labor market has reduced. The unemployment rate is the number of workers looking for work divided by the labor force. So, an aging population tends to lower the measure of the unemployment rate.

Second, tight labor markets can fuel inflation through rising wages that get passed along to consumers. However, at this point, the low unemployment rate in Canada does not appear to be fueling significant wage growth. From the start of this year until May, there were signs of a pickup in wage growth—it reached 3.9 percent year over year for permanent employees. However, over the four months ending in September, wage growth slowed to 2.2 percent. Sustained low unemployment should ultimately bid up wages and this is why the Bank of Canada will need to gradually tighten monetary policy.

Interest rates and the Canadian dollar

The temperate rise in wages provides some breathing room to the Bank of Canada. The bank estimates that an overnight rate of 2.50–3.50 percent is the neutral level where it neither provides stimulus to the economy nor applies the brakes. Accordingly, the declining slack in the labor market calls for the bank to reduce the amount of monetary stimulus, but the tame wage picture means that it need not hike rates quickly and aggressively. The bank is expected to hike by 75 basis points in 2019, lifting Canadian bond yields. Slower economic growth in 2020 should lead the Bank of Canada to hold off raising interest rates further.

The Canadian dollar received a boost when the USMCA was announced, but the Federal Reserve may raise rates by more than the Bank of Canada, and commodity prices may retreat as global growth slows, weakening the Canadian dollar vis-à-vis the US dollar.

Summary

The Canadian economy will likely deliver a solid performance this year, although economic growth will be slower. However, this represents a gearing down to a more sustainable pace of expansion. In 2019, the pace of growth should remain moderate at close to, or slightly below, 2.0 percent. Prospects in 2020 look more challenging. It is likely that the loss of fiscal stimulus and higher US interest rates will lead to significantly slower US economic growth. Canada is well integrated into North American supply chains and economy. Together, these factors may put the country at risk of much slower growth in 2020.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.