Economic impact of epidemics and pandemics in Asia since 2000 COVID-19 will likely be harsher than others

8 minute read

20 May 2020

Asia’s experience with health care crises reveals that economic activity is impacted through sectors such as consumer spending, tourism, and aviation. The impact of COVID-19, however, will likely be harsher given its scale and social-distancing measures.

In January 2020, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) was expecting global growth to pick up this year with emerging and developing Asia1 set for a slight uptick in economic activity.2 Yet, in a world of COVID-19, forecasts made as recently as a few months ago can quickly lose their significance.3 Given that COVID-19 has now spread across the world and there’s no known treatment or vaccine till the writing of this article, the fortunes of Asia and the world economy have changed sharply—the IMF now expects a global recession.4 In Asia, strong social-distancing measures have already hit consumer spending, production, and services; tourism and aviation too have slowed sharply.5 Any resumption of economic activity to pre-virus levels will now depend on how the fight against COVID-19 progresses and how scarred do consumers and businesses emerge from this pandemic.6

Learn more

Learn more about connecting for a resilient world

Explore the Economics collection

Learn about Deloitte's services

Go straight to smart. Get the Deloitte Insights app

But it’s not the first time Asia is dealing with a pandemic or epidemic—the region has had its share of health care crises. In 2003, several countries in the region were affected by Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS). Six years later, H1N1 struck at a time when the region was still making its way out of the global financial crisis of 2008–2009. And in mid-2015, South Korea had to deal with cases of the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS). The impact of COVID-19, however, may be much worse given its sheer scale. Yet, analysis of the economic impact of previous health care crises in this century may offer some insights on what to expect this time and how soon Asian economies can find their way once the current pandemic runs its course.

2003: The economic scars of SARS

SARS made its presence felt in Asia between November 2002 and July 2003,7 with China being the most affected, followed by Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Singapore. Other Asian economies—Vietnam, the Philippines, Malaysia, and Thailand—were also impacted, albeit to a lesser extent. Overall, nearly 8,068 people tested positive for SARS in Asia alone; 773 of them died.8

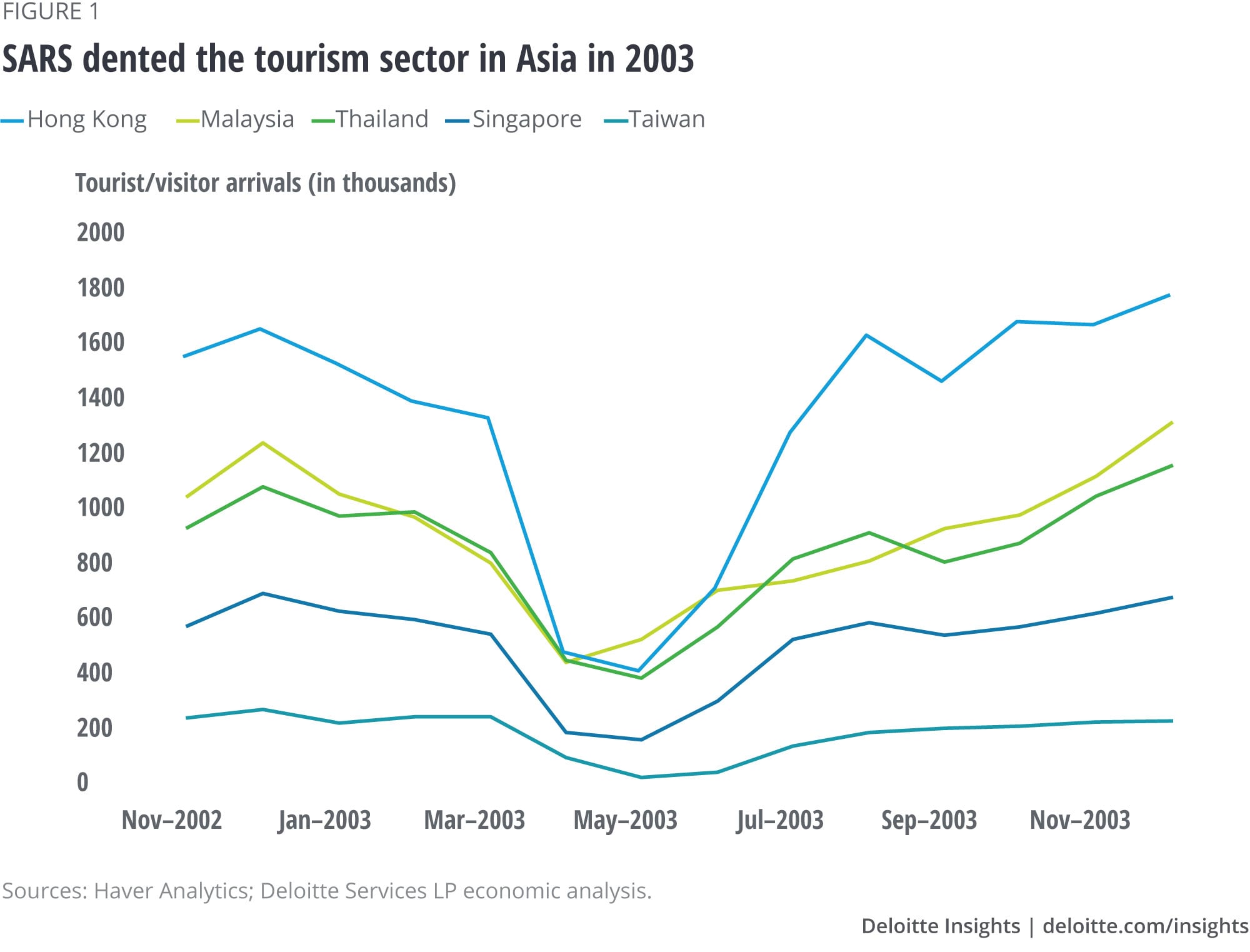

SARS hit economic activity in the affected countries and certain sectors bore the brunt more than others. Tourism and aviation, for example, were hit hard. Between January and July of 2003, tourist arrivals per month fell year over year9 on average—by 33.8 percent in Taiwan and by 30.0 percent in Singapore. Thailand and Malaysia saw strong declines too (figure 1). A key impact of falling tourist numbers was the hospitality industry. Hotel occupancy in Hong Kong, for example, fell to an average of 26.7 percent per month in Q2 2003 from 82.3 percent in the previous quarter.10 And according to the World Travel and Tourism Council, China suffered a 25 percent reduction in tourism-related GDP with a loss of 2.8 million jobs.11

Restricted tourism and travel unsettled aviation. Passenger traffic at the Changi Airport (Singapore) fell by 48.5 percent in Q2 2003, from a 1.8 percent increase in the same period a year before.12 At the Hong Kong International Airport, passenger traffic fell 68.9 percent in April and 79.9 percent in May.13 According to the International Air Transport Association (IATA), Asia Pacific airlines lost 8 percent in revenue per kilometer and US$6 billion in total revenues in 2003, much of it due to SARS.14

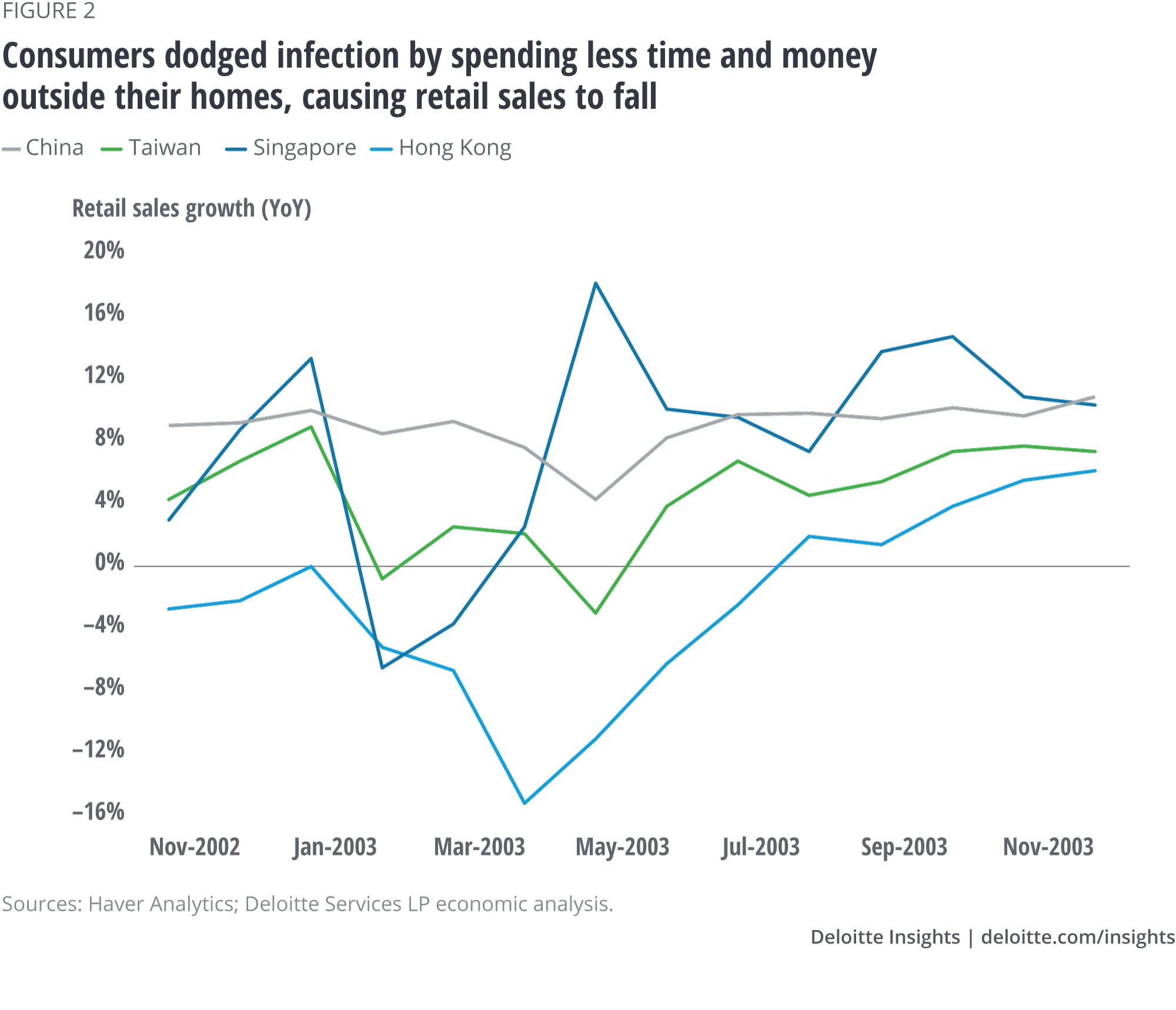

The threat of infection caused consumers to spend less time and money outside their homes. In Q2 2003, retail sales growth slowed to 6.8 percent in China from 8 percent in the previous quarter. The hit to sales was even greater in Taiwan and Hong Kong—retail sales fell by 15.2 percent in April in Hong Kong (figure 2). Food services places, such as restaurants, suffered greatly as people avoided contact with others.15 Food and beverage services sales fell by 20 percent in Q2 2003 in Singapore and by 10.7 percent in Taiwan. And in Hong Kong, business receipts in food services fell 19.4 percent that quarter.

The hit to sales was even greater in Taiwan and Hong Kong—retail sales fell by 15.2 percent in April in Hong Kong

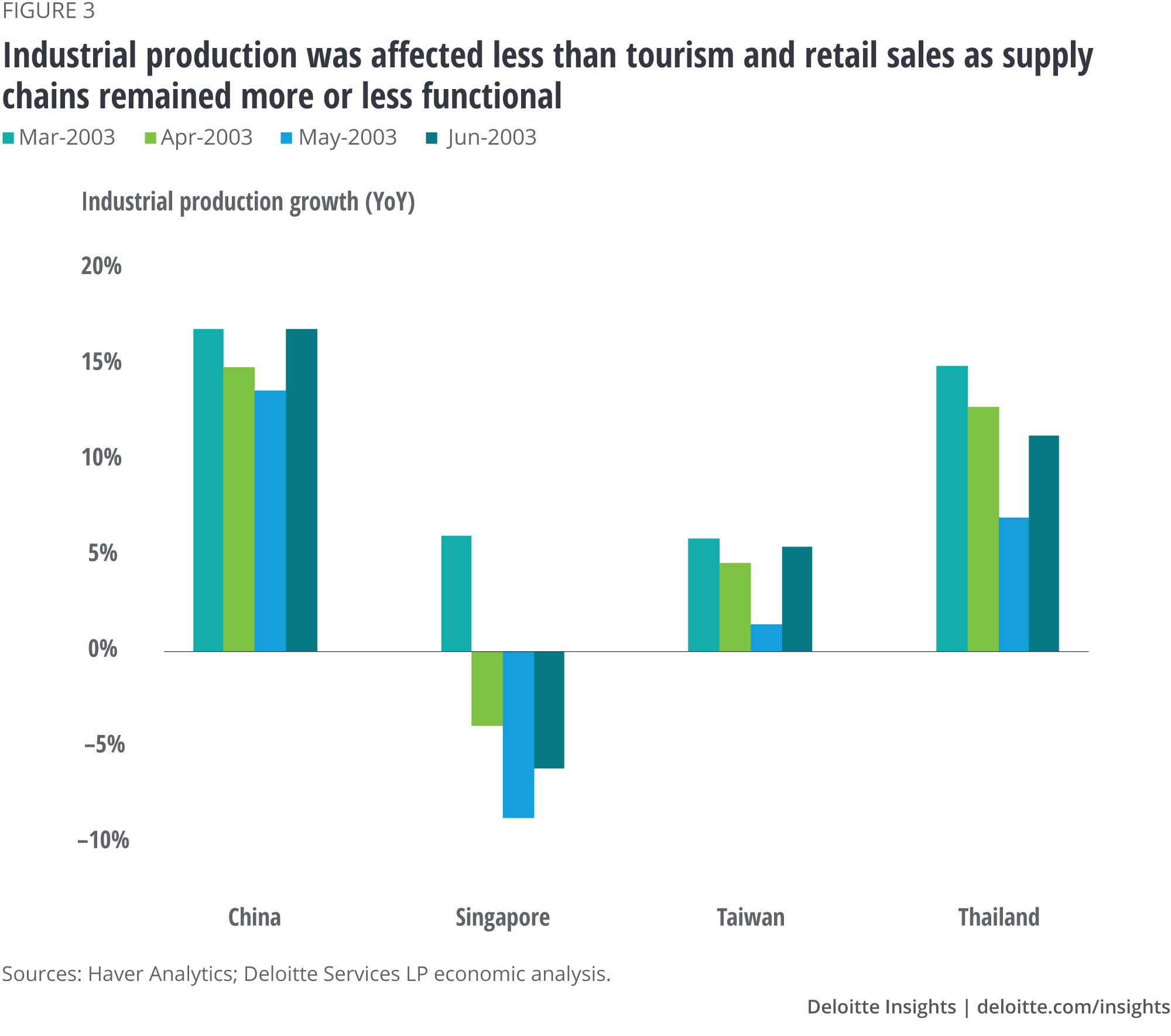

The SARS outbreak also weighed on industrial production, although not as much as it did on tourism, hospitality, aviation, retail, and food services. In China, industrial production growth slowed in April and May of 2003, with May being the slowest that year (figure 3). Thankfully, the outbreak didn’t impact supply chains—whether within Asia (such as those between Hong Kong and China)16 or with the rest of the world—to a great extent.

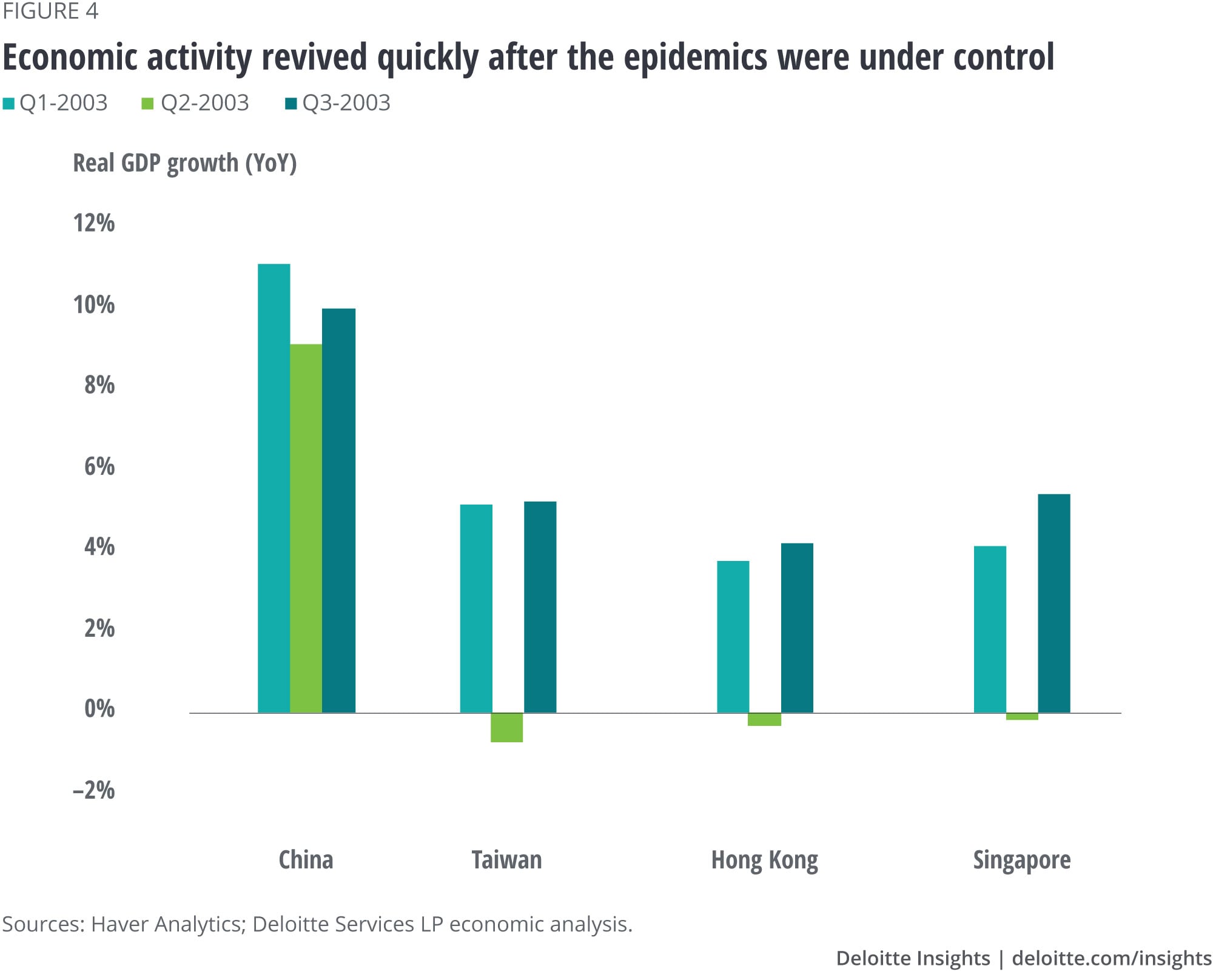

As a result, GDP growth suffered in SARS-affected economies in 2003. Economic activity contracted in Taiwan, Singapore, and Hong Kong in Q2 2003, while in China, real GDP growth slowed to 9.1 percent from 11.1 percent in Q1 2003 (figure 4). The IMF analysis points to the virus’ impact on key sectors in denting economic activity in SARS-affected countries in the first half of 2003, if not the whole year.17 Fortunately, once the epidemic was under control, the recovery in economic activity was relatively swift—economies recovered within the year (figure 4).

2009: H1N1 at the time of the global financial crisis

The impact of the H1N1 outbreak on Asian economies is harder to isolate, given that it travelled to Asian shores in the first half of 2009,18 when the region and the wider global economy were still dealing with the effects of the global financial crisis. While the global downturn impacted domestic demand in Asia, exporters had to contend with weak external demand as key importers such as the United States and those in Europe were either still in recession or just recovering from one.

The impact of H1N1 would have added to the existing weakness in economic activity in the region, mostly impacting economies through the same channels as happened during the outbreak of SARS—through tourism, aviation, and consumer spending. Thailand and Hong Kong, for example, saw a sharp fall in visitor arrivals in Q2 2009. While a large part of this decline in tourism was due to the global downturn of 2008–2009, Q2 2009 was also a time when cases of H1N1 were rising in Asia. Interestingly, that Asia escaped the worst of the H1N1 pandemic is evident from reviving tourist inflows in the second half of 2009. Tourism in North America (Mexico, in particular), in contrast, took a much longer time to recover given the intensity of the H1N1 outbreak there.19

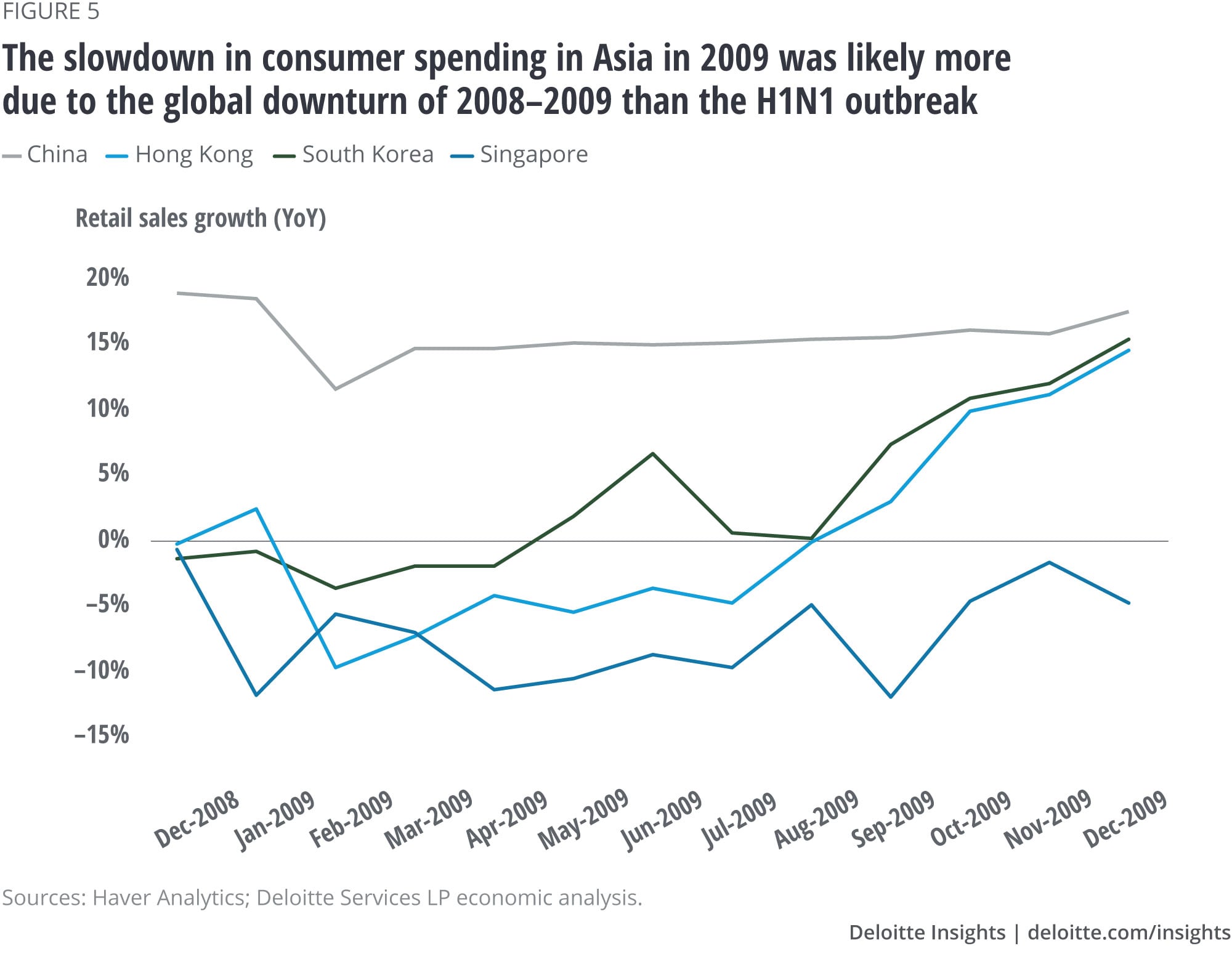

It is a bit harder to identify the impact of H1N1 from that of the global downturn on indicators other than tourism, such as retail sales and industrial production. Retail sales, for example, suffered during the second and third quarters of 2009 (figure 5). Yet it is not clear how much of this had H1N1 to blame. Likely, the global downturn had a bigger impact on sales than the pandemic. This is true of industrial production as well. During the SARS outbreak, industrial production was not impacted much. Not so in 2009 when production was down in key economies in the second quarter—16.1 percent in Taiwan and 5.4 percent in South Korea. That production was hit even in countries (such as India) not affected much by H1N1 is an indication that a slowdown in industrial activity in Asia at that time likely had more to do with the global downturn than the pandemic.

2015: MERS cast a shadow over South Korea, not the rest of Asia

The impact of MERS on Asia was limited to South Korea in May, June, and July of 2015.20 Tourist arrivals fell by 41.3 percent in June and 54 percent in July. As concerns spread, consumer spending dropped. Retail sales contracted 0.5 percent in June. Restaurants and food services places were also affected as spending by consumers and foreign tourists declined—estimates put the decline in food and beverage services due to the fall in tourist arrivals at US$359 million.21 All these weighed on overall economic activity with South Korea’s real GDP in Q2 2015 growing by just 0.2 percent compared to the previous quarter; part of this decline in growth was also due to an unrelated slowdown in exports. But once the MERS outbreak eased, the economy bounced back in Q3.

What’s happening now: Economic activity was hit hard in Q1

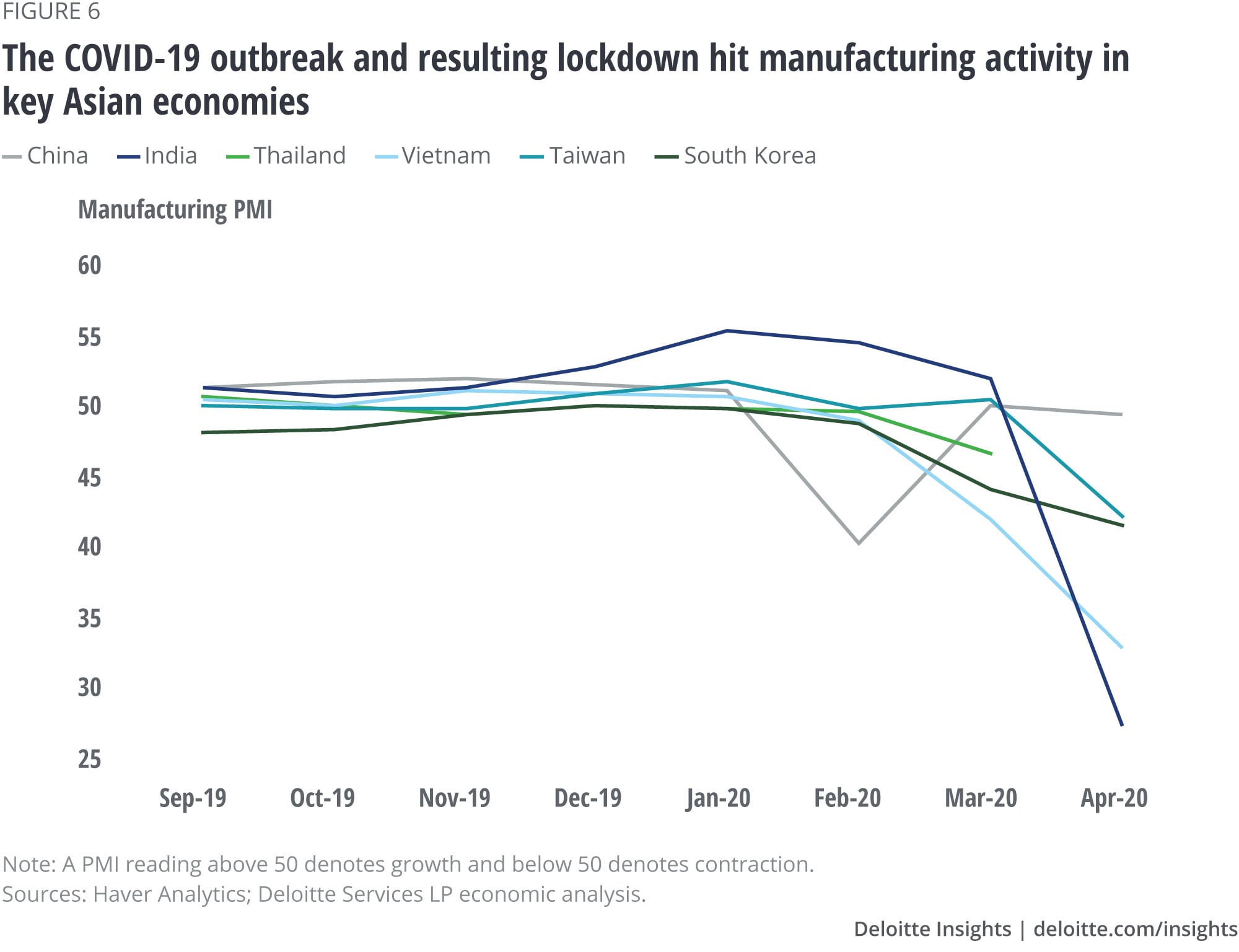

Latest economic indicators point to a sharp slowdown in the region in Q1 2020 due to the COVID-19 outbreak. In China, GDP contracted by 6.8 percent in Q1 with value added in industry declining by 13.5 percent in January and February. The Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI) data reveals weak manufacturing activity in India, South Korea, Vietnam, Malaysia, and Thailand (figure 6). Interestingly, manufacturing bounced back in March in China and Taiwan, likely indicating a recovery as both countries flatten the curve of the outbreak.

Services also suffered as households hunkered down and most retail businesses closed. Retail sales fell in China by 19.6 percent in Q1. Motor vehicle sales were down a staggering 42.4 percent during the same period. Retail sales have been affected in other countries as well such as India, Singapore, Taiwan, and Hong Kong. Social distancing has manifested itself in less sales at food services places. In Singapore, for example, the value of food and beverage services sales fell 23.7 percent in March. In India, the services PMI indicated a sharp contraction in April, and it is likely that services may contract again due to continued restrictions on movement and economic activity.

As for tourism and aviation, tourist arrivals were down a staggering 98.6 percent in Hong Kong, 85.0 percent in Singapore, and 76.4 percent in Thailand in March. The average occupancy rate in hotels in Hong Kong fell to 31 percent in March from 60 percent in January. Countries have restricted both international and domestic travel, hurting aviation. Latest estimates by IATA put potential passenger revenue drop in Asia Pacific at US$113 billion this year.22

But this pandemic is different—in both scale and likely impact

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on Asia will likely be worse than other epidemics and pandemics due to three key reasons. Firstly, the scale of the current pandemic is much larger than any other health care crisis this century. Total SARS cases worldwide in 2003 were 8,437. In the COVID-19 pandemic, there are already about 4.2 million confirmed cases globally as of May 12 and counting, with 286,355 deaths reported.23 In Asia, China has 84,011 cases while India has 70,827.24

Secondly, state-mandated social distancing in Asia (and the world over) now is way more severe than in the past.25 For example, India with a population of 1.3 billion still has strong social distancing measures in place, a massive shift from 2003 when SARS had hardly any impact on the country. At the height of the COVID-19 outbreak in China, nearly 760 million were in lockdown; while restrictions have been eased now, advise on social distancing continues. Other countries in Asia have also ramped up social-distancing measures as the number of cases rise.26 Social distancing of this magnitude will likely have a deeper impact on durable goods spending, food services, tourism, aviation, and industrial production than before.

Finally, Asia plays a bigger role in the world economy and is more interconnected with the rest of the world now than at the time of SARS. Asia’s share in global GDP was an estimated 33.2 percent in 2019, up from 22.7 percent in 2003.27 Its share in global exports went up to 32 percent from 24.7.28 Major exporters in Asia will therefore have to contend with a likely downturn in key markets in Europe and the United States—Deloitte’s US economic forecasts point to a likely 8.3 percent GDP contraction (with a 50 percent probability) this year in the best-case scenario.29

Current trends reinforce expectations that the likely economic loss in Asia due to COVID-19 will be large. Oxford Economics forecasts GDP growth in Asia to fall to just 1 percent this year from 4.5 percent in 2019.30 And according to S&P Global Ratings, the Asia-Pacific region is likely to witness a permanent income loss of US$620 billion due to the current pandemic.31 While the current projections seem grim, a lot will depend on how the pandemic evolves and how governments respond to it. Faster containment will allow Asian economies to recover more easily. Continued rise in cases, however, may mean a more staggered revival in economic activity. People and policymakers in Asia will certainly be hoping for the former.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.

Explore our Covid-19 content

-

Embedding trust into COVID-19 recovery Article4 years ago

-

The heart of resilient leadership: Responding to COVID-19 Article5 years ago

-

Confronting the COVID-19 crisis Podcast5 years ago

-

COVID-19 and the virtualization of government Article4 years ago

-

The essence of resilient leadership: Business recovery from COVID-19 Article4 years ago

-

Opportunities for private equity post-COVID-19 Article4 years ago