The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act: Untangling claims about the latest tax reform bill has been saved

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act: Untangling claims about the latest tax reform bill Behind the Numbers, February 2018

27 February 2018

The recently introduced tax reform bill has evoked mixed—and, sometimes, extreme—responses. So is it really great for the economy, as some believe, or is it simply increasing the wealth of high net worth individuals, as others claim? Here, we provide our perspectives on some commonly asked questions.

Want an advanced lesson in spin? Just listen to some people talking about the economic impact of the recent tax reform bill. Depending on who is speaking—or writing—it’s either the greatest thing for the economy or it’s a generous gift to people who do not need it. Any debate quickly gets caught up in a web of claims about economic data and models. In addition, part of the plan is temporary . . . maybe. So the plan’s impact may look very different five or ten years from now. It all depends on whether a future Congress decides to make the “temporary” changes permanent.

Here’s a guide to thinking about the impact of tax reform on the economy, and sorting out which claims are sensible and grounded in proven economic theory.

Q: How do the tax changes affect the overall economy?

A: The tax bill’s economic impact operates through two channels. First, the tax cut in the bill reduces overall tax bills for many—but not all—individuals and businesses. Of course, the tax cut has to be financed by more federal borrowing. Second, the bill finances those changes in part by reducing many tax deductions.

Q: Let’s start with the tax cut, because everybody likes paying less taxes. Just how large is the tax cut?

A: Individuals would get a net tax cut of $75 billion in 2018, out of total personal income of about $18 trillion, rising to $139 billion by 2025. Businesses would get a net tax cut of $130 billion in 2018, but the tax cut would be about $49 billion by 2027.1 Some of the business tax cut is offset by higher tax collections on the international income of US corporations.

Q: Why did you give the individual tax cut for 2025 but the business tax cut for 2027?

A: Most of the individual tax changes are reversed after 2025. In fact, the Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) estimates that net individual tax collections will be $83 billion higher in 2027 than if the tax plan had not been adopted. This is also true for one key part of the business tax change. “Bonus depreciation,” which allows businesses to write off investments more quickly than normal, will be phased out starting in 2023 and will go away completely after 2026. And “bonus depreciation” allows businesses to lower their taxes today at the expense of higher taxes in later years (when they would have had depreciation to expense, had they not used it earlier).

Q: Who came up with those numbers?

A: The staff of a Congressional Committee called the Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) has the job of estimating the “cost” of any proposal to change tax laws. The staff—which is nonpartisan—has deep expertise in modeling and estimating the impact of tax changes. The changes are estimated for a 10-year horizon, reflecting Congressional rules about budgeting.

Q: More money in the pockets of businesses and individuals sounds like it should make GDP grow faster. How much growth will it create?

A: No question about it, the “tax cut” part of the bill will create some extra economic activity. Additional business cash flow is likely to create more investment spending,2 and higher after-tax incomes will induce households to spend more on goods and services. This is the demand side impact of the tax bill. By some estimates, it could be fairly large in the short run. The International Monetary Fund, for example, estimates that US GDP will be 1.2 percent higher in 2020 because of the additional demand.3

Q: Wait, why did you emphasize “short run”?

A: Because the demand side impact is likely to go away. Once the economy reaches capacity, additional demand creates inflation, not more growth.

Q: But isn’t the economy already close to capacity? How can it grow faster if there is a labor shortage?

A: There probably isn’t a labor shortage yet.4 Many people—including the staff and officials at the Federal Reserve—think we may be getting close. That means that the Federal Reserve is becoming more worried about the possibility of inflation. The additional demand from the tax cut may convince Fed officials to raise interest rates faster than they otherwise would have, and that might moderate the growth impact of the tax cut.

Q: But won’t lowering the tax rate and making the tax code more business-friendly increase investment and the capacity of the economy?

A: Yes, it’s not just putting money in people’s pockets. There should be a supply side impact from this tax cut—a reduction in the cost of investing that will convince organizations to invest more, increasing productivity.

Q: How large is the supply side impact?

A: It’s likely to be much smaller than the demand side impact in the next few years. However, after 10 years, the demand side impact will likely have dissipated, and the only impact we will see is on the supply side.

Table 1 compares the estimated impact after 10 years from four different organizations that use “dynamic scoring” to analyze the impact of the tax cut. The estimates range so widely because the different models make different assumptions about taxpayer behavior. The Tax Foundation’s estimates imply that GDP growth could be approximately 0.3 percentage points greater per year with the new tax bill (2.3 percent, for example, rather than 2.0 percent) while the JCT’s estimates suggest almost no impact.

Q: Doesn’t the tax bill add to the long-term debt problem?

A: Yes. Even under the most optimistic assumptions, the federal debt is projected to be higher in 2027 than it would have been had the tax bill not passed. Figure 1 compares projections for the debt by the different estimators. The figure shows that all models indicate the tax bill raising total US government debt by at least $1 trillion.

Source: Joint Committee on Taxation, Tax Foundation, Penn Wharton Budget Model, and Tax Policy Center.

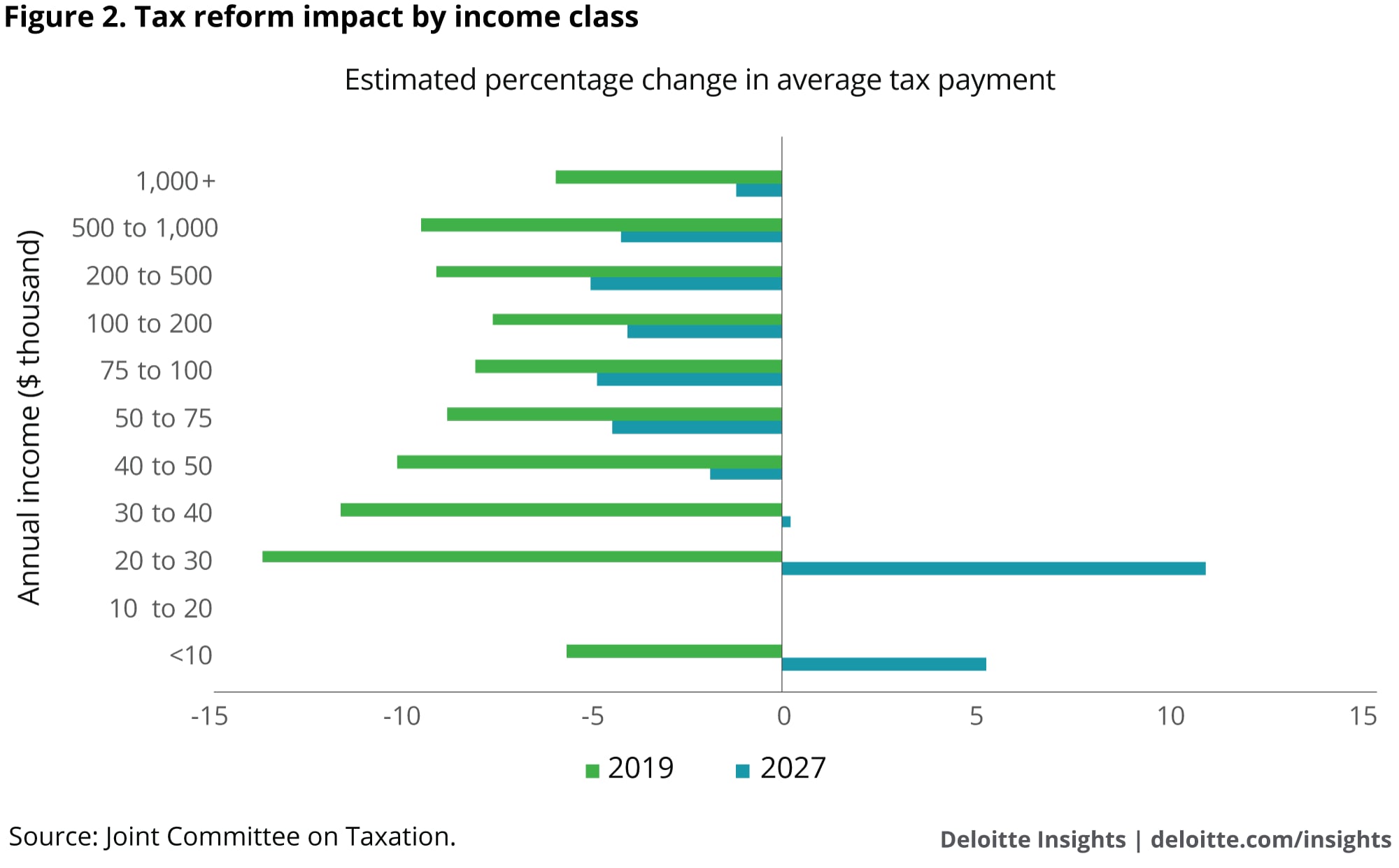

Q: Does the tax bill only benefit wealthy people?

A: That depends on whether the temporary individual tax changes are included. Figure 2 shows the impact on the average taxpayer6 in each income class in 2019 (when the individual tax changes are in place) and in 2027 (when most of the individual changes will have been reversed).7 Initially, average taxpayers at all income levels will receive cuts, with the largest percentage decline going to relatively low-income taxpayers—those with incomes between $20,000 and $30,000 per year. After the individual tax changes are reversed, however, those same low-income taxpayers face a rise in tax payments (27 percent for the $20,000–$30,000 income range) compared to the current law. (That is due to the complicated impact of the permanent repeal of the penalty for not buying health insurance.8)

Of course, most taxpayers are not average. Actual experience will depend on the specifics of each taxpayer’s situation.

Q: As always, economists make things complicated. Let’s cut to the chase. What’s your “elevator speech” about the economic impact of the Tax Cut and Jobs Act?

A: Most of the research agrees that there will be a modest, but significant boost to growth in the short run. By the end of the 10-year horizon—and beyond—the impact will likely be small at best. Despite some provisions’ negative impact on high-income households (e.g., marriage penalty and disallowance of state and local deductions), the bill appears to provide the most benefits to people in upper-middle-income classes—although if the individual changes become permanent, people in lower brackets will benefit in the long run as well. However, the additional long-run debt may cause problems for the United States further down the road.