Seven strategies to limit fraud, waste, and abuse of COVID-19 relief dollars Program integrity during the recovery

14 minute read

30 June 2020

Lauren A. Allen United States

Lauren A. Allen United States Dave Mader United States

Dave Mader United States John O'Leary United States

John O'Leary United States Mahesh Kelkar India

Mahesh Kelkar India

With the US government having to quickly administer COVID-19 economic relief funding, there is risk of funds not being used properly. Here are seven strategies governments can use to ensure the integrity of relief spending.

Introduction

The distribution of US federal funds devoted to COVID-19 pandemic relief represents an unprecedented program integrity challenge. Not only is the relief effort large—currently standing at US$2.9 trillion with additional funding possible—but these programs have unique characteristics that make it challenging to ensure that the dollars go to intended recipients and achieve intended results. These characteristics include:

Learn more

Learn more about connecting for a resilient world

Explore the government & public services collection

Learn about Deloitte's services

Go straight to smart. Get the Deloitte Insights app

- Uniquely fast—A sense of urgency drove both the passage and distribution of relief funds. The US Congress passed relief legislation quickly, and within days trillions of dollars began flowing from Washington. It was urgent that agencies quickly distributed the relief where it was needed.

- Uniquely complex—Unlike the recovery from the financial crisis of 2008, COVID-19 relief funds flow from a large array of federal agencies, including the Department of the Treasury, Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), Small Business Administration, the Department of Health and Human Services, the Department of Education, and the Department of Labor. They, in turn, target a wide array of recipients (individuals, businesses, state and local governments) and flow through a variety of channels (direct from the federal government, through state-administered programs, through municipalities and local agencies, and through financial institutions).

- Uniquely novel—Several programs are new, including the Pandemic Unemployment Assistance (PUA) program and the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP). By definition, these new programs kicked off without the benefit of established application processes, and operated with newly introduced, untested integrity controls.

How should governments approach this unprecedented challenge of program integrity? And how can they achieve the goal of fast and accurate disbursement with clear accountability for impact?

The answer should be a combination of established program integrity practices as well as approaches specific to the unique challenges of the COVID-19 relief effort. Immediate steps to consider include:

- Conducting fraud risk assessments (FRAs)

- Focusing on targeted analytics using new data sources to mitigate fraud, waste, and abuse (FWA)

- Using nudge thinking to encourage accurate and voluntary compliance

- Building oversight readiness at the federal level

- Establishing central project management offices (PMOs) at the state level

- Applying an enterprise risk management (ERM) and fraud risk management (FRM) lens to relief funding

- Using collective intelligence to advance data- and information-sharing capabilities

UNPRECEDENTED COVID-19 ECONOMIC RELIEF IN THE UNITED STATES

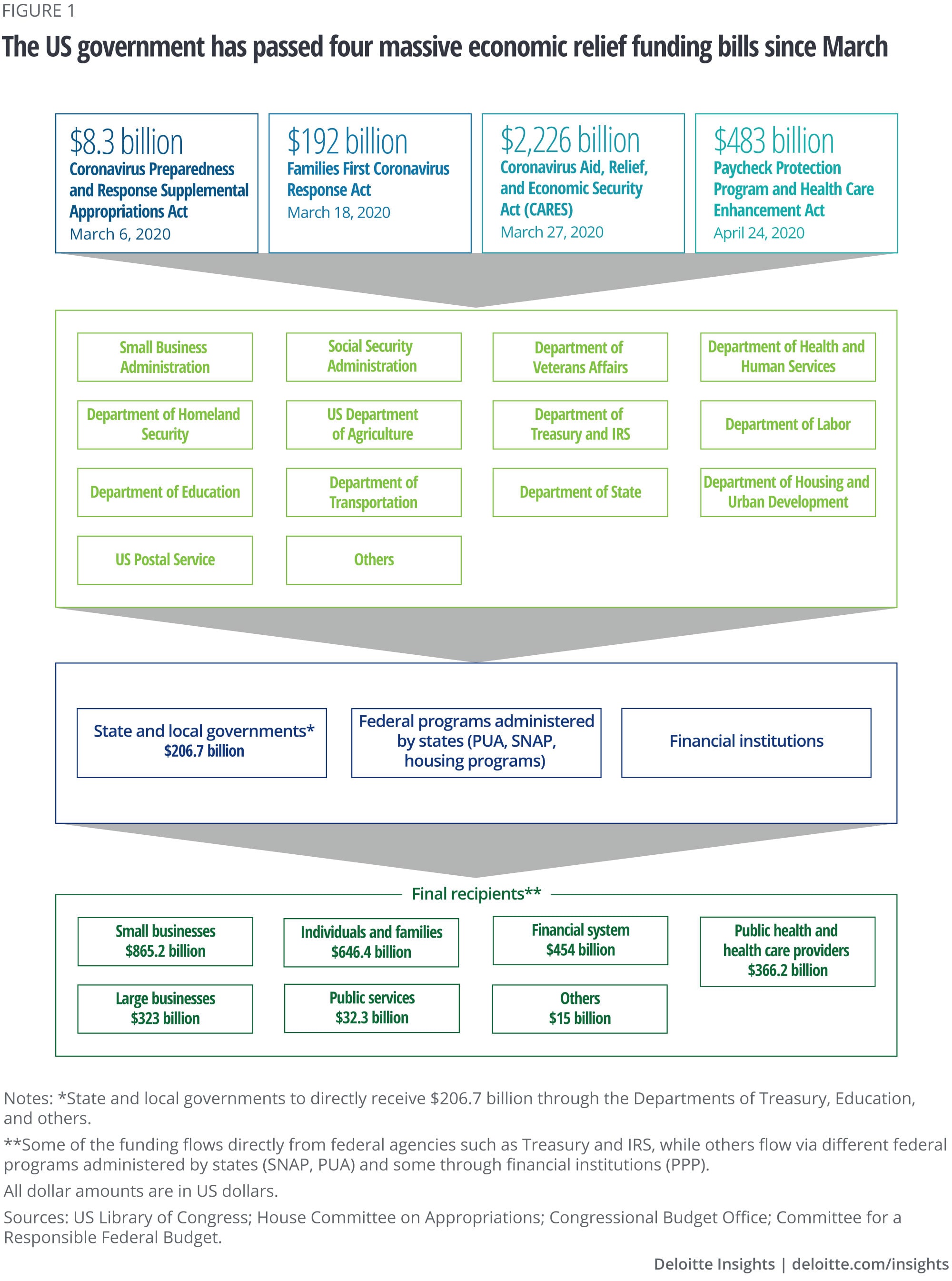

As shown in figure 1, the funding is channeled through numerous federal agencies, some with limited experience with disaster-related programs of this sort. Much of this funding has already been distributed, and with this speed has come challenges regarding improper payments.

The flow of funds is complex, with money going to individuals, businesses, and government through a wide array of federal and state administered programs. For example, the Internal Revenue Services is making direct payments to individuals as tax credits, while the Department of Treasury will be looking to support state and local economies with US$150 billion. The Small Business Administration plans to support small businesses through two tranches of funding amounting to US$670 billion.1 Meanwhile, the Department of Labor has expanded the state-administered unemployment insurance benefits, adding US$600 in weekly benefits and making gig workers eligible for the first time ever under the new PUA program.2

Integrity challenges can be a problem even for established government programs. In March 2020, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) estimated that improper payments by federal agencies totaled US$175 billion in 2019,3 more than the 2019 state budgets of Colorado, Michigan, Minnesota, Pennsylvania, and North Carolina combined.4

Prior federal emergency relief efforts provide some perspective on the complexity and vastness of current relief funding. Between 2005–2008, Congress appropriated roughly US$121.7 billion in hurricane relief funding.5 After Hurricane Maria hit Puerto Rico in 2017, FEMA administered more than US$3 billion in public assistance funds.6 Though sizable, these funding programs represent a small fraction of the current US $2.9 trillion COVID-19 relief funding effort. In addition, most disaster funding is regionally isolated, impacting just a few states or jurisdictions, and comes from a small handful of federal funding sources. In contrast, the current relief effort is nationwide and flows through multiple channels to many different types of beneficiaries.

New COVID-19 relief programs require special focus on program integrity

In previous disasters, federal funding was typically provided through established grant programs that had the necessary grant-making process, program controls, and oversight infrastructure in place. The current economic stabilization packages introduce many new funding sources and programs. Some of the complexities challenging program integrity include:

- The desire to distribute funds quickly can foster a reactive (pay-and-chase) approach to program integrity, which can be costly and resource-intensive.

- A massive influx of applicants can overwhelm agency staff.7

- A lack of funding and oversight infrastructure in new programs may increase improper payments.

- Flexing existing policies and controls can increase risk tolerance in specific cases and may invite bad actors.8

Public officials administering these funds are in a difficult spot. They are being asked to stand up processes, take in applications, and get money out the door as soon as possible—but to also minimize errors. This need for speed can contribute to improper payments.

In May 2020, reports emerged of a sophisticated international fraud ring that apparently submitted thousands of false unemployment claims in at least seven states, siphoning off millions in unemployment benefits and other CARES Act funding. These scammers used personal information such as names, addresses, and Social Security numbers to file false claims and bilk the system of millions of dollars.9

Public officials are being asked to stand up processes, take in applications, and get money out the door as soon as possible—but to also minimize errors.

However, unlike fraud, improper payments could be unintentional due to issues in program design and lack of clear program rules. For example, the PPP funded forgivable loans to help small business owners pay their employees and support other expenses such as rent, mortgage interest, or utilities.10 The initial funding of US$349 billion was exhausted in the first 13 days as companies scrambled to get the loans, and there were reports of large corporations obtaining large loans while many smaller businesses came away empty handed.11 Congress then added an additional US$320 billion in funding for the program. An additional US$6.8 billion was announced to fund Community Development Financial Institutions (CDFI) to primarily support underserved, low income areas.12

To add to the challenge, it was decided that banks would administer these loans to ensure speedy disbursement, but different banks had different online processes and different requirements for granting the loans, creating confusion among small business owners.13 As greater clarity around the requirements for using the funds became clear, many businesses revised their applications and returned the funds rather than risk being penalized for inadvertently violating program rules.14 In some cases, businesses applied to multiple banks out of concern that the money would be gone and were improperly granted multiple loans.15 In June 2020, Congress passed legislation to amend the PPP to address some of these issues.16 How else can governments adapt to these new realities?

Seven steps governments can take to enhance program integrity

The seven strategies discussed below can help governments at all levels ensure that funds have their intended impact.

No. 1: Conducting fraud risk assessments

The COVID-19 relief programs will almost certainly give rise to phone, email, and phishing scams to siphon off relief funds. There are reports of multiple unemployment insurance scams already underway.17 Conducting a fraud risk assessment as soon as possible, given the speed and urgency of disbursement, can help minimize the negative impact of these intentional fraud efforts. Agencies can use technology to monitor social media to find new fraud risks, as many scams are openly perpetrated through open source mediums.

By continuously monitoring the external risk environment, agencies can identify trends in fraud to mitigate new schemes and scams. Some of these monitoring methods often include detecting unusual payment patterns to recipients, vendors, and partners. Such an approach not only can detect fraud but may discourage it, as potential scammers could be wary if they know their behavior is being watched.

An internal federal government memo in May warned of increasing evidence of identity theft attacks taking place in half a dozen or more states.18 Since most identity theft fraud begins with social media and phishing operations, social media analysis can also be a useful tool to probe fraudulent claims. Some government agencies at the forefront of cyber strategy have cracked this code by infiltrating the dark web to anticipate, neutralize, and disrupt hackers.19 Similarly, government agencies focusing on benefits programs should consider building their sensing capabilities for detecting new fraud schemes in the dark corners of the internet and building strategies to mitigate them.

No. 2: Focusing on targeted analytics using new data sources to mitigate FWA

Especially during the current period of rapid fund disbursement, data and analytics should be foundational to an agency’s portfolio to fight FWA. The ability to use the data you have, and to quickly access readily available public data from a variety of sources can be critical in detecting possible fraud. While it will often take human expertise to confirm behavior and intent, data is often a critical first step in identifying improper payments.20

How much data is a good starting point for analysis? The more the better. In the short term, internal data combined with social media scans may be all that is possible. For instance, the Social Security Administration (SSA) has successfully used social media data to arrest more than 100 people defrauding the Social Security Disability Insurance program. By reviewing the social media account of disability claimants, investigators were able to find proof of fraud through photos and videos.21

In the longer term, applying an analytics layer to a broad, multisourced database can provide a valuable look into fraud patterns hidden in transaction data. The United States Postal Service (USPS) has used analytics to identify anomalies such as multiple billings for the same vehicle in vehicle maintenance contracts for its 470,000-mail-delivery-truck fleet. In 2018, the analytics system helped the USPS avoid making US$110 million in improper payments and collect US$121 million in fines.22 A similar data-driven approach helped the Maryland state comptroller reduce improper tax refunds. Having found higher fraud rates in taxes filed by local tax firms, the office scrutinized these filings more—and stopped US$35 million in tax refund fraud.23

Such forensic data analysis can be most effective when coupled with human intelligence. A classic example comes from Medicaid. If most psychotherapists bill for 45-minute sessions, a doctor who frequently charges for 60-minute sessions might merit additional scrutiny. But while the data can surface an anomaly, it can rarely establish intent, and it may require a layer of human intelligence to determine fraud. Human judgement can augment data analysis and apply tacit knowledge of a benefit program’s rules, practices, and gray areas.24

Data from outside the agency, including commercial data sets, can further boost insights. For example, the Bureau of the Fiscal Service, part of the Department of Treasury, has a Do Not Pay (DNP) analytics platform that can help federal agencies prevent improper payments made to vendors, grantees, loan recipients, and beneficiaries.25 By harnessing the power of data from multiple sources—credit alert systems, the death master file from the SSA, excluded individuals and entities database, the system for award management, and more—DNP can quickly determine the eligibility of recipients.26

No. 3: Using nudge thinking to encourage accurate and voluntary compliance

Soft-touch behavioral interventions, commonly known as nudges, can be particularly well suited to encouraging accurate self-reporting by would-be beneficiaries. Relatively inexpensive communications, delivered digitally through emails, pop-up messages, or chatbots, can yield significant benefits.27

For example, to reduce overpayments in its unemployment insurance program, the state of New Mexico, in 2014, applied the principles of behavioral insights. It introduced some simple, low-cost nudges to claims process with promising results. The Department of Workforce Solutions designed a simple pop-up message such as “Nine out of 10 people in your county accurately report earnings each week.” These messages nearly doubled the self-reported earnings, directly translating to substantially lower improper payments.28

Behavioral nudges can be an important tool in an agency’s toolkit to fight FWA of COVID-19 relief funds. Small interventions in the benefits application process could nudge better compliance with program guidelines. For instance, by asking small businesses to confirm their eligibility for PPP while highlighting relevant rules can both educate and encourage more accurate responses.

No. 4: Building oversight readiness at the federal level

As relief funding bills are passed, there has been a scramble to establish the precise level of oversight and scrutiny of these funds. Congress has put in place three mechanisms to oversee spending through the CARES Act.29

- The Pandemic Response Accountability Committee (PRAC) will include inspector generals (IGs) from at least nine federal agencies and will oversee outlays for the entire bill.

- Special Inspector General for Pandemic Recovery, a new office in the Department of Treasury, will specifically oversee the US$500 billion economic relief to large businesses.

- The Congressional Oversight Commission, a bicameral-elected five-person group, will oversee the stimulus and relief funding activities carried out by the Department of Treasury and the Federal Reserve Board.

In addition to these three mechanisms, the GAO has been allocated US$20 million in the CARES Act for oversight of pandemic-related spending.30 In June 2020, the PRAC released its first report that highlighted challenges faced by 37 different federal agencies in administering and managing CARES Act funds. One of the biggest challenges identified by the different IGs was financial and grant management of these relief funds. The IGs specifically noted challenges around accuracy of reporting data, incompatible integrity controls for new funding streams, and assessing grants performance in achieving intended results. In addition, IGs highlighted concerns around telework, safeguarding federal systems against cyberattacks, and maintaining essential services during the pandemic.31

These oversight bodies will need to coordinate efforts and avoid duplication to improve oversight efficiency—similar to the federal-level coordination in the 2008 economic crisis. Then, the Recovery Accountability and Transparency Board (RATB) and the Special Inspector General for Troubled Asset Relief Program (SIGTARP) were two crucial institutional entities set up to oversee stimulus funding. The SIGTARP investigations have helped to recover more than US$11 billion through actions against corporations, while the RATB has recovered more than US$157 million.32 The RATB also created the “Recovery.gov” portal that ushered in a new era of transparency and accountability in federal stimulus and relief payments.33

No. 5: Establishing central PMOs at the state level

Within the CARES Act, under the Coronavirus Relief Funds program, approximately US$150 billion of the US$2 trillion economic relief package was designated for state, local, and tribal governments. It also earmarks an additional US$56 billion funding for K-12, higher education, and public transit systems.34 The Treasury department has issued guidance and placed limitations on how this money can be spent. Most notably, the fund cannot be used to fill shortfalls in government revenue or to serve as a source of revenue replacement—but precise interpretations of these rules will be tricky.35

Given the complex nature of state budgets and varying sources of relief funds, states are facing a large accounting, tracking, and reporting burden to demonstrate how relief funds are being deployed. If states are unable to demonstrate how these funds are being put to use, there could be potential clawbacks and ex post facto denials of payments from the federal government. These gray areas are expected to put pressure on states to carefully administer these relief funds in order to demonstrate all requirements are being met.

To address these challenges, states should consider creating a central PMO to coordinate relief activities across state agencies, including applying for funds, documenting their use, and reporting on the impact of the spending. This PMO could leverage existing oversight capabilities that might reside within a state’s Treasury, Budget, State Controller office, or other financial centers. By centralizing expertise and given an appropriate governance structure, the PMO office can provide states with the ability to make strategic choices, as in some cases a single expense type might qualify for different programs with different reimbursement rates. A PMO can closely monitor how all funds are spent, and make it easier to communicate with federal agencies, including auditors and IGs, as well as state citizens. For example, for education relief funding, the office could help to identify how many dollars were spent purchasing educational technology to support online learning.36 Taking this a step further, the office could help to quantify how many students used the technology and who otherwise would not have been able to continue their learning.

With the increased scrutiny on the large volume of funding, a central PMO can increase the level of transparency by focusing on how the funds are administered and for what intended outcomes.

No. 6: Applying an ERM and FRM lens to relief funding

ERM helps agencies deal with risk, helping to improve decision-making and program outcomes. ERM focuses on creating a culture of risk awareness that proactively identifies potential sources of risk, providing agencies with tools to limit negative outcomes. Using ERM, for example, a state unemployment agency might identify many different types of risks, including:

- Individuals underreporting their earnings, thus overcollecting benefits

- Organized fraud rings submitting false claims

- Hackers stealing claimants’ cyber identity information

Categorizing these different risks allows an agency to adopt appropriate prevention and mitigation strategies.

In addition, risk appetite and risk tolerance are typically key elements of an agency’s ERM strategy. The GAO fraud risk management framework states that agencies can waive or postpone certain protocols to focus on increasing the speed of funding, thus increasing risk tolerance in certain cases. For example, in the postpandemic environment, with agencies focused on disbursing funds quickly, a government agency may decide to postpone a home inspection for temporary housing assistance funding.37

No. 7: Using collective intelligence to advance data- and information-sharing capabilities

Collective intelligence is not a new concept. It’s common sense that many people working together can be smarter than one or two highly capable people working alone, and it’s obvious that organizations are more effective when the right hand knows what the left hand is doing. The notion of collective intelligence can take many forms and can encompass either formal or informal processes for sharing information, solving problems, and making decisions.38

The ability to easily share data across organizational boundaries can be difficult but is often critical to fraud detection, as with individuals collecting from the same program in different states.

In the current COVID-19 crisis, we have seen collective intelligence networks arise to help develop vaccines, therapeutics, DIY test kits, and outbreak models.39 Additionally, the value of a collective intelligence model is well entrenched in areas such as cyberthreat intelligence and analysis. For example, the city of Los Angeles’ Integrated Strategic Operations Center processes cyberthreats by collecting information from a wide network that includes the Department of Homeland Security, the FBI, and both the private and nonprofit sectors.40

As agencies undertake fraud risk assessment to understand the changing risk environment, tapping into a broader network could be highly beneficial. For instance, the nonprofit Better Business Bureau specializes in raising awareness on scams that could impact individuals, businesses, and governments. It was one of the first organizations to publish a scam alert on coronavirus relief funding in March 2020.41 By tapping into such networks, federal, state, and local agencies can improve their fraud intelligence capabilities and proactively adjust program controls.

A good example of collective intelligence at work to mitigate FWA comes from the state of Tennessee. TennCare, Tennessee’s Medicaid program, established a collective intelligence program in 2015 by working closely with managed-care organizations (MCO) in its network. TennCare required MCOs to share information on health care providers who were under fraud investigation. These detailed records helped TennCare map “normal” and abnormal behavior in the system. This knowledge base enabled the state to spot trends in fraud, share institutional knowledge, identify overpayments, and disseminate best practices to all MCOs. The effort helped TennCare drop 250 providers from the Medicaid network in the first year, saving nearly US$50 million.42

Another example of a data-sharing model between states that could help reduce FWA is the National Accuracy Clearinghouse, funded by the Department of Agriculture. The pilot program in five states reduced the number of dual participations in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program43 and could potentially save nearly US$114 million annually, if expanded nationally.44

The ultimate goal: Limit improper payments, maximize impact

Maintaining program integrity and reducing FWA of economic relief funds can be challenging for governments, based on experience in past crises. Some level of improper payments is inevitable when funds are disbursed so quickly; however, oversight bodies will be reviewing previous and future relief funding.

By considering the seven strategies discussed in the paper, agencies can address three key challenges related to overseeing these public funds:

- Limiting FWA by targeting the biggest risks using technology and business tools.

- Coordinating activities within the organization and building oversight readiness.

- Building a greater level of accountability and transparency in disbursement of COVID-19 relief and stimulus funds.

With additional relief and stimulus funding likely, this is the time for agencies across governments to reinforce and streamline their program integrity processes. After all, every dollar spent improperly will be an opportunity lost, while every dollar spent well can add economic value and save lives.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.

More on COVID-19

-

The heart of resilient leadership: Responding to COVID-19 Article5 years ago

-

The essence of resilient leadership: Business recovery from COVID-19 Article5 years ago

-

The long and short of short-time work amid COVID-19 Article4 years ago

-

New architectures of resilience Article4 years ago

-

COVID-19 and the undisruptable CEO Article4 years ago

-

COVID-19 insights Collection