Volatility in emerging economies: Is contagion too harsh a word?

04 August 2018

Emerging economies are facing challenges such as capital outflows and financial market losses, raising fears of a contagion. But such fears may be unfounded as these economies have moved to more flexible currency practices, preventing sudden depreciation.

In May, Argentina reached out to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) for a line of credit to tide over a period of sharp fall in the peso and rising inflation. The move provoked strong reaction from the Argentine public, wary about the difficulties surrounding the crisis of 2001–2002 and the IMF’s unpopular intervention then.1 Of more concern was the sudden reversal in fortunes of a country which only less than a year back was winning accolades for reforms—in June 2017, the country had sold US$2.75 billion of 100-year bonds amid strong demand from investors.2

Learn More

Subscribe to receive more economics content

Argentina, however, is not the only country to be caught up in a sudden swell of economic and financial opinion turning against some emerging economies. From Latin America to Asia, emerging economies are witnessing capital outflows as many investors eye interest rates hikes in the United States. This has contributed to weakening currencies and financial markets, with deteriorating domestic economic conditions in some countries adding to the volatility. Rising oil prices have likely not helped either and nor have potential trade-restrictive policy headwinds against global trade. No wonder then, that, there are potential fears about a contagion in emerging economies.3 The truth, however, is likely a bit more nuanced. Although some emerging economies appear to be under pressure, concerns about a contagion and comparisons to previous crisis such as the Asian financial crisis are likely overblown.

What’s stoking the general disgruntlement?

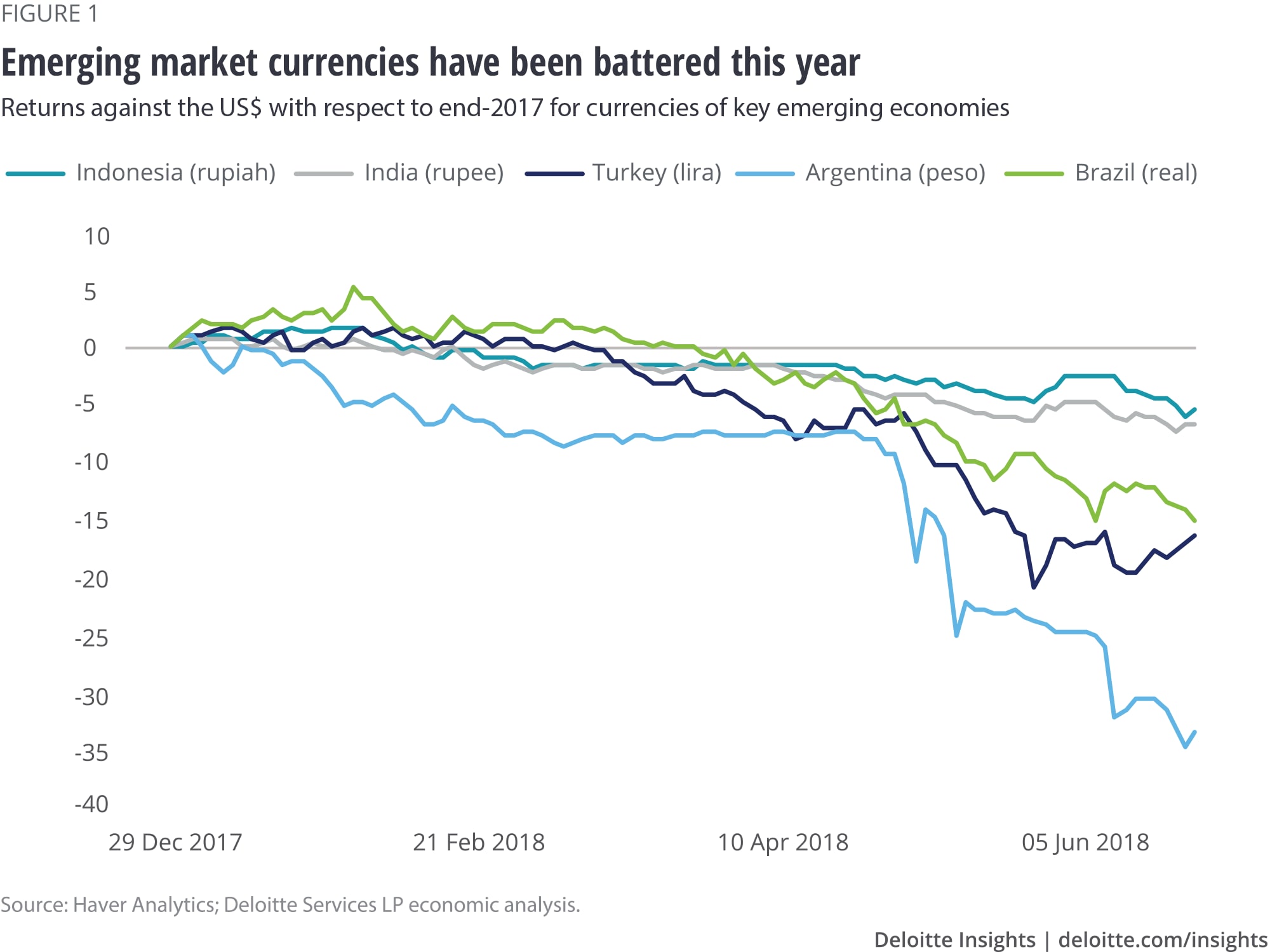

For some, rising concerns about emerging economies may seem surprising. It shouldn’t be. With the United States Federal Reserve (Fed) on a rate hike path—it has raised rates by 150 basis points (bps) in the last two years—and the European Central Bank (ECB) also talking about a move away from loose monetary policy, global liquidity is suddenly turning away from emerging economies.4 For example, in May alone, foreign investors pulled out (net) US$12.3 billion worth of funds from emerging markets, the largest outflow since November 2016.5 This, in turn, has hit many emerging market currencies (figure 1).

Adding potential fuel to the fire is higher oil prices, especially for oil importers such as India, as this can pose risks for inflation and their external balances. Brent crude, for example, is up by 16.1 percent this year (as of early July) after rising by 17.4 percent in 2017.6 Consequently, from 1.5 percent year over year in January, petrol prices’ growth in India climbed to 10.3 percent in May. And if rising oil prices and volatility in global liquidity were not enough, the risk of a trade war between the United States and others seems much higher compared to 2017. Tit-for-tat tariffs not only can pose the risk of higher prices for consumers and businesses, but also cause disruptions in supply chains. For example, any curbs on China’s exports will hit its export-linked supply chains with South East Asia—nearly half of overall trade between South East Asia and China is made up of intermediate goods.7 Similarly, any tariffs on auto imports into the United States can hurt Mexico (and Canada), a key component of the North American auto supply chain.8

Domestic economic fundamentals have also played a part

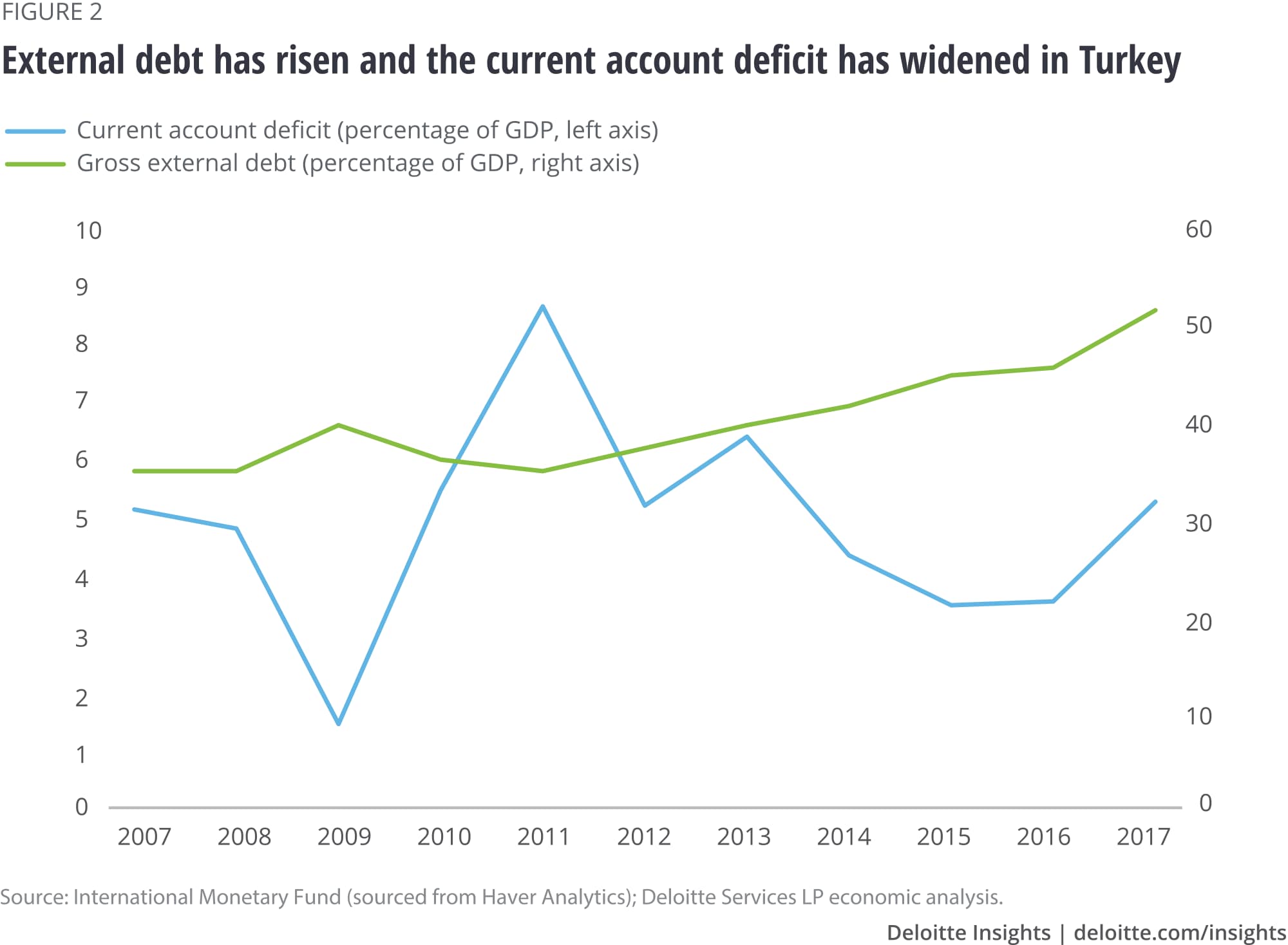

Unfortunately, the current bout of elevated risk for many emerging markets also comes at a time of political uncertainty in some economies and domestic risks in others. In Brazil, for example, political uncertainty ahead of presidential and legislative elections has contributed to putting the reforms agenda—likely critical for improving fiscal health and pushing up potential GDP growth—on hold. Neighboring Argentina witnessed challenges in capital and currency markets after it raised its inflation target, clouding perceptions regarding the central bank’s independence.9 This, along with recent challenges in global liquidity, likely contributed to the dent in investor confidence for many and sent the peso into a steep fall. Similarly, in Turkey, worries over central bank’s independence, along with a high current account deficit and rising external debt (figure 2), have hit the lira.

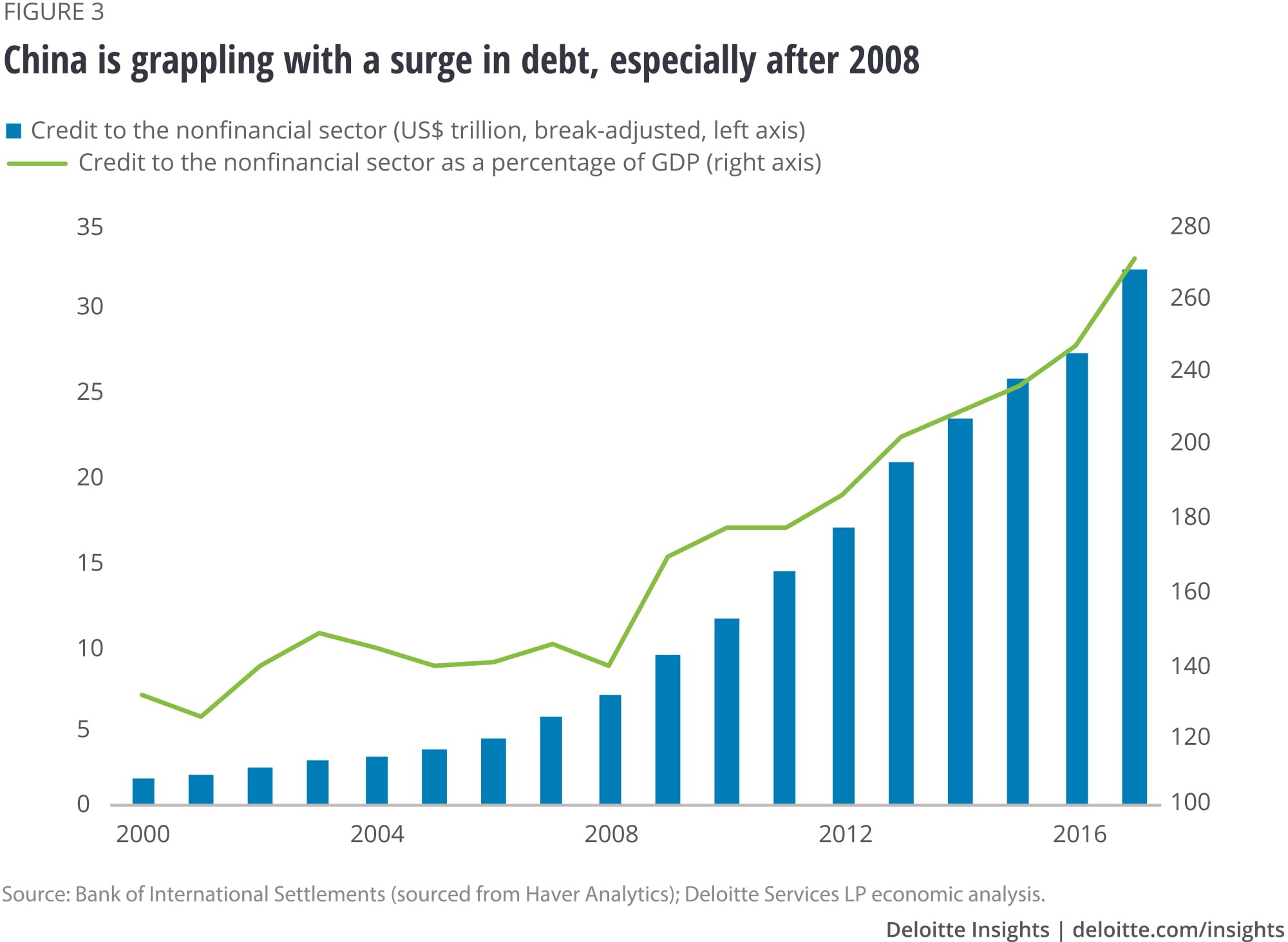

Asia also has its own share of challenges. High household debt and an unexpected election win for the opposition in Malaysia have raised uncertainty for many over the fate of reforms such as the goods and services tax (GST).10 In China, the government is keen to bring down debt levels—credit to the nonfinancial sector in the world’s second largest economy has surged from 143.5 percent of GDP in 2008 to about 270.0 percent in 2017 (figure 3). In neighboring India, the road map to fiscal prudence may be thwarted if oil prices keep rising in the year until federal government elections in 2019; the government may then be tempted to keep a lid on fuel prices, thereby raising the subsidy bill—a strategy that Indonesia has resorted to at the cost of fiscal health.11 India also appears to be struggling with deteriorating asset quality in commercial banking—nonperforming loans made up 11.8 percent of total loans in Q1 2018—which, in turn, has dented credit creation and raised risks to the banking sector.12

Contagion, however, is unlikely

In such a scenario, questions are naturally emerging about a return to a crisis akin to the Asian financial crisis of 1998 or even worse, the Great Recession. The truth, however, is likely a bit more nuanced, with fears of a contagion and comparisons to previous crises potentially overblown.

First, there is no currency peg now for most emerging economies, other than for Hong Kong (Special Administrative Region), thereby removing the threat of sudden depreciation or devaluation as happened during the Asian financial crisis.13 Back in those days, key East Asian currencies had a de-facto peg to the US dollar. Sudden outflow of capital during the crisis and, in some cases, abrupt adoption of a more flexible currency thereafter contributed to sharp drop in currencies in the region.14 For example, the Indonesian rupiah fell by more than 75 percent against the US dollar and the South Korean won and Malaysian ringgit by more than 50 percent during 1997–1998.15 Things have changed since then. Many economies have moved to a more flexible currency regime—akin to a managed float—which, in turn, has helped prevent any sharp and sudden depreciation. The current bout of currency depreciation, for example, is far lower than what happened during the Asian financial crisis.

Second, aiding the stability mechanisms are the foreign exchange reserves that economies have accumulated over time (figure 4). In 1997, India, for example, had foreign exchange reserves amounting to just over US$30.0 billion; by May 2018, that had risen to US$412.8 billion. China, currently, is sitting on about US$3.2 trillion worth of reserves. These buffers are likely enough to tide over short-term shocks and to support the currencies during that period. The role of external debt and, within it, short-term external debt has also reduced over time, removing the kind of vulnerabilities last witnessed during 1997–1998 (figure 4). Moreover, for many of these economies barring Turkey, current account balances are relatively in check, thereby restoring some sense of parity in their international transactions.

Third, aiding many a government is the fiscal space to tide over any downturn in growth. Indonesia, for example, has put a cap on administered prices (read fuel), thereby keeping inflation in check. While this is likely to increase the government’s subsidy bill and push the deficit wider than the budgeted 2.2 percent, continued prudence elsewhere in the budget and the need to retain ratings upgrades will likely limit the deficit to less than the binding level of 3.0 percent.16 In India, although the deficit is higher, the government has stuck to the fiscal road map so far. As revenues from GST, now one year in operation, filter in, fiscal health will likely receive a boost and so will the continuation of market-based rates for fuel, despite some political pressure to cap prices.17 Even in Turkey, which is facing problems in its external balances, the budget deficit is under control (1.5 percent of GDP in 2017). The same is true for China, where the central government has enough capacity to infuse fiscal stimulus, if the need arises.

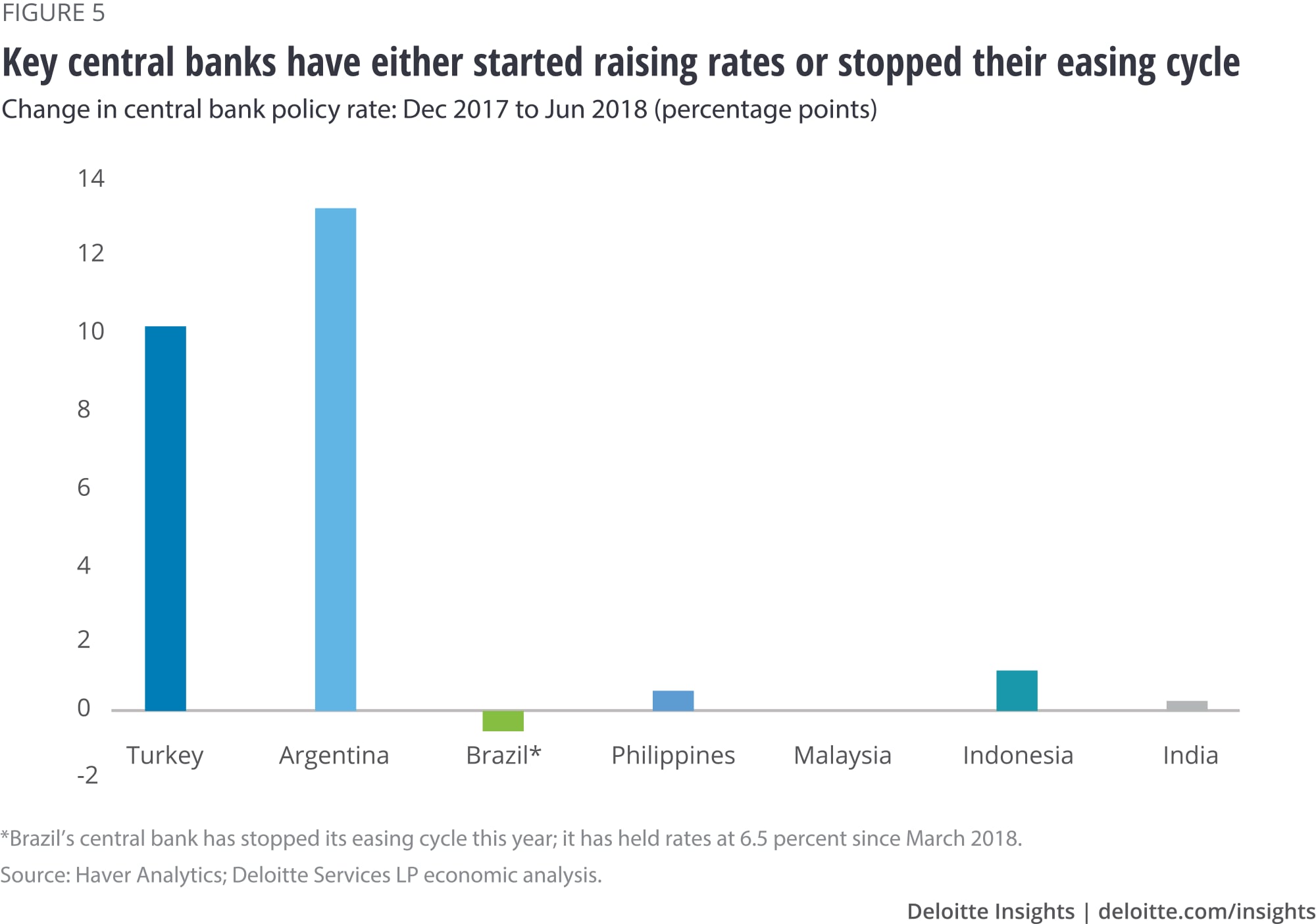

Finally, policymakers appear to be taking note of problems before they spread. Be it China trying to curb high debt levels, including cracking down on shadow banking, or Argentina reaching out to the IMF before things go further south, there are efforts underway to help tackle the current bout of domestic and external irritants before they spread.18 Moreover, central banks have shifted tactics to handle any further currency weakening and inflationary pressures—they have either refrained from easing further (like in Brazil) or hiked rates (figure 5). Even in Argentina and Turkey, central banks have been bold to raise rates steeply. These moves are likely to keep currency weakening in check, although growth may suffer.

Aim for the long term

Argentina may have the relatively toughest road ahead to recovery. For Brazil and Turkey, a lot likely depends on policy framework post elections. In the former, the race is still unclear at this stage, thereby likely pushing up the uncertainty regarding the policy road map. Turkey, on the other hand, will likely have to find ways to bring back central bank credibility now that the elections are over. Political uncertainty will likely also be playing out in India and Indonesia where elections are slated for 2019. Meanwhile, for supply chains across Asia and Latin America, fortunes will likely be determined by how the brinkmanship over tariffs plays out between the United States and others. While policymakers dealing with these myriad challenges may be tempted to focus more on short-term volatility, it could be unwise to take their eyes off structural reforms. It may just win them the favor of foreign investors and domestic constituents alike. And that, too, over a longer period.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.