Partnerships for the Future has been saved

Partnerships for the Future Redefine public/private cooperation

20 March 2013

- Lauren Rosenbaum, Edward Van Buren, John Mennel

The growing complexity of social and economic challenges is driving new, innovative forms of collaboration between governments and businesses.

While public-private partnerships (PPPs) have occurred in the United States for at least 200 years,1 they have primarily involved large infrastructure projects with formal contractual agreements, considered too costly or risky for one side to take on alone. But the increasingly complex nature of our national challenges, along with recent shifts in economic and social forces, are creating incentives for government and business to collaborate more frequently and in new ways that go well beyond traditional infrastructure investments, expanding the definition of partnerships in the future.

Overview

EXPLORE

Create and download a custom PDF of the Business Trends 2013 report.

Traditionally, government and business had few incentives to actively collaborate. For the most part, government regulated business, and business lobbied government on areas of economic interest. When partnerships did occur, they were usually undertaken to invest in large infrastructure projects through formal contractual agreements, as represented in the National Council for Public Private Partnerships’ definition of PPPs:

Public-private partnership: A contractual agreement between a public agency (federal, state, or local) and a private sector entity. Through this agreement, the skills and assets of each sector (public and private) are shared in delivering a service or facility for the use of the general public.

Get the full Business Trends 2013 report from the “Download a PDF” link in the left margin, or select individual chapters to download from the “Create a Custom PDF” link below it.

Today’s challenges for the United States—including an unprecedented recession and fiscal crisis, global warming, terrorism, the Afghanistan conflict, and crises in healthcare and education—are changing the equation. There is a sense that these problems are increasingly complex, requiring new responses. Faced with mounting pressure to resolve these complex challenges, government is introducing regulations to prevent future crises, and seeking innovation to execute its mission more effectively with fewer resources. In spite of these actions, there is an increasing recognition from government that it cannot solve these challenges alone.

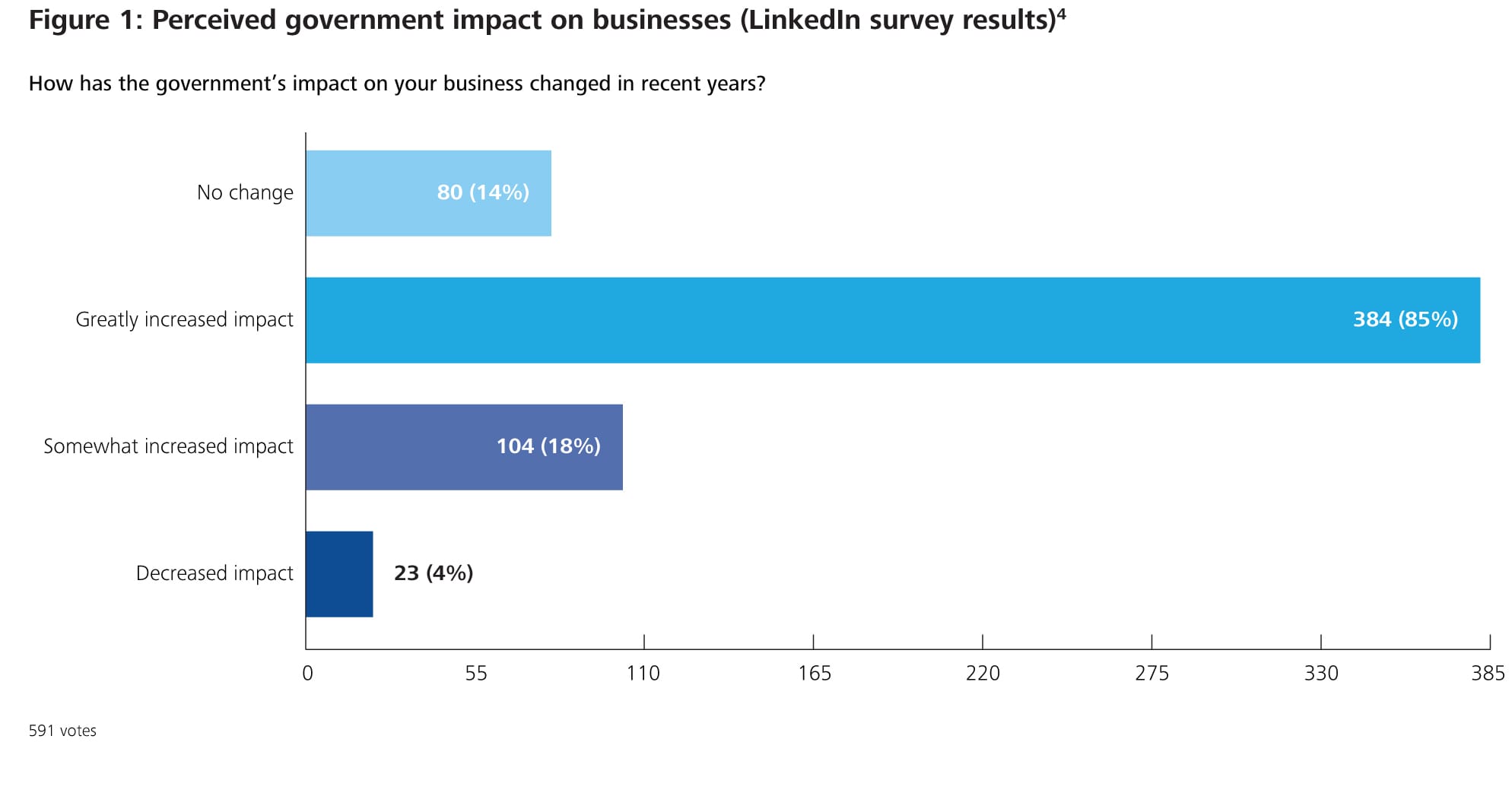

Meanwhile, in the business world, there is also an increasing recognition that these challenges, as well as the government’s response, represent both a threat and opportunity. The impact of government behavior on business was evident in a recent Deloitte LinkedIn poll of more than 500 senior executives, which found that 82 percent of respondents believe government’s influence on their business has either greatly or somewhat increased in recent years.2 This seems to indicate that business leaders acknowledge that something fundamental is changing in their relationship with government. The question is, what will come next? Lobbying spending rose dramatically in response to new regulations in recent years,3 but government and business are also starting to take more creative approaches to collaborating. Both sides seem to realize that business problems are now government problems—and vice versa—and both are proactively intensifying new approaches to partnership at the highest levels.

Meanwhile, in the business world, there is also an increasing recognition that these challenges, as well as the government’s response, represent both a threat and opportunity. The impact of government behavior on business was evident in a recent Deloitte LinkedIn poll of more than 500 senior executives, which found that 82 percent of respondents believe government’s influence on their business has either greatly or somewhat increased in recent years.2 This seems to indicate that business leaders acknowledge that something fundamental is changing in their relationship with government. The question is, what will come next? Lobbying spending rose dramatically in response to new regulations in recent years,3 but government and business are also starting to take more creative approaches to collaborating. Both sides seem to realize that business problems are now government problems—and vice versa—and both are proactively intensifying new approaches to partnership at the highest levels.

What’s driving this trend?

The complexity of the current challenges and changes occurring at the political and macro-economic level have fundamentally changed the federal government’s traditional behaviors, creating new incentives for partnership. Here are a few examples of these changes.

See endnote 4

Complexity of national challenges

The challenges facing the US government are becoming increasingly complex. For instance, education used to be about building a system that would deliver basic skills to children through high school. Now it can be about creating highly specialized training that is delivered well into adult years, evolving as the needs of business change over time. Protecting the environment used to be about developing local and national regulations and subsidizing improved technology to mitigate industrial pollution. Now, protecting the environment often involves dramatically reducing the burning of fossil fuels not just in one industry in one city, but across multiple uses and in countries all over the world. As a result of these types of fundamental shifts, government is increasingly looking to business for resources and new approaches to these challenges. The business world has an incentive to help solve them both out of a sense of social responsibility, and because they affect economic growth and the bottom line.

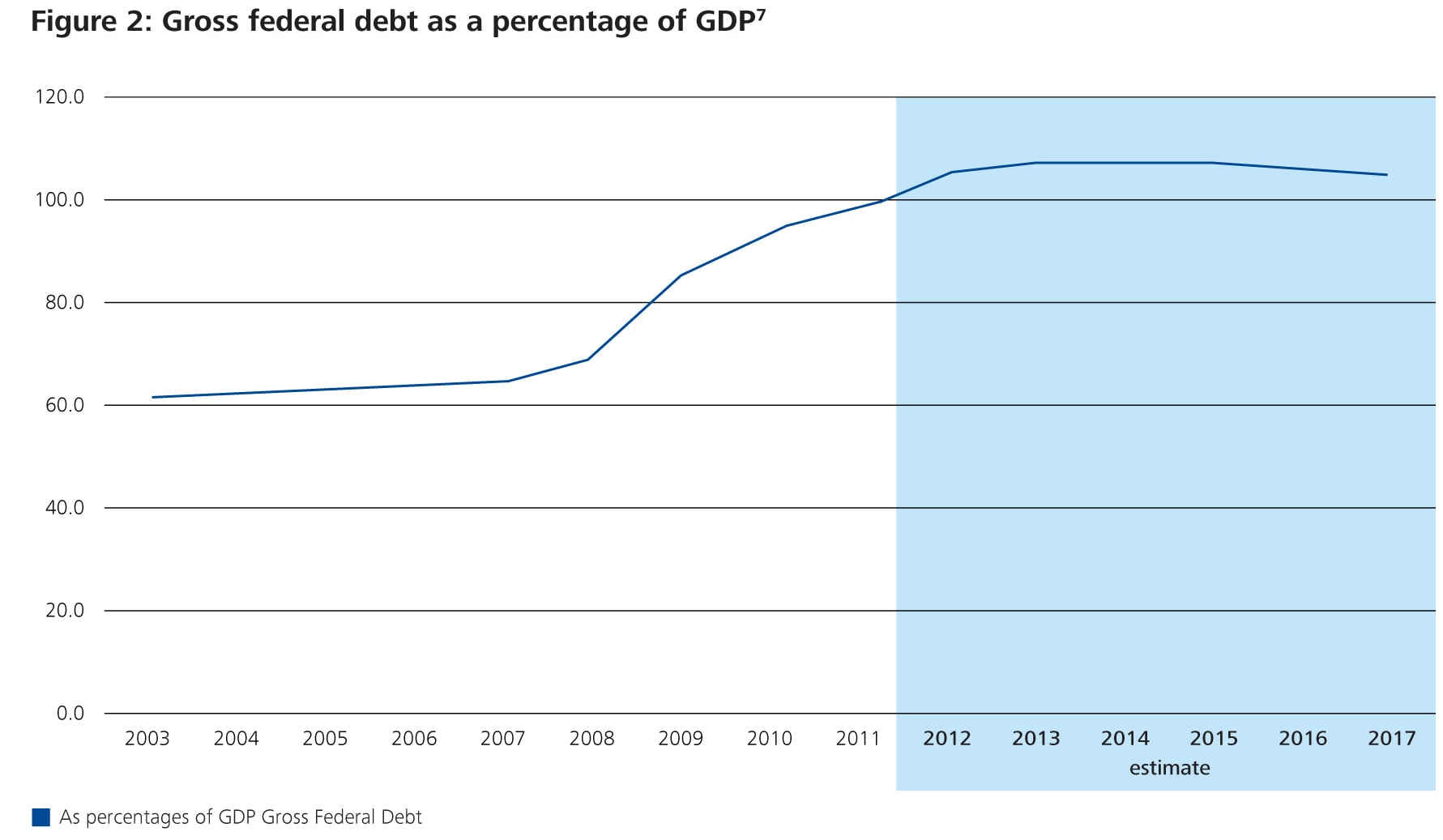

See endnote 7

Cost reduction

Not only must government solve more complex problems, but they must do so with fewer resources. In the last five years, gross federal debt rose sharply as a percentage of GDP (figure 2).5 The federal government is under tremendous pressure to reduce costs. Federal discretionary spending has already declined—by 3.4 percent between 2010 and 2011 and by 2.07 percent between 2011 and 2012.6 With government looking to reduce costs, there will likely be an incentive to cooperate with business on joint investments or to open up opportunities for business to provide services traditionally performed by government, creating a new opportunity for private sector growth.

Re-regulation

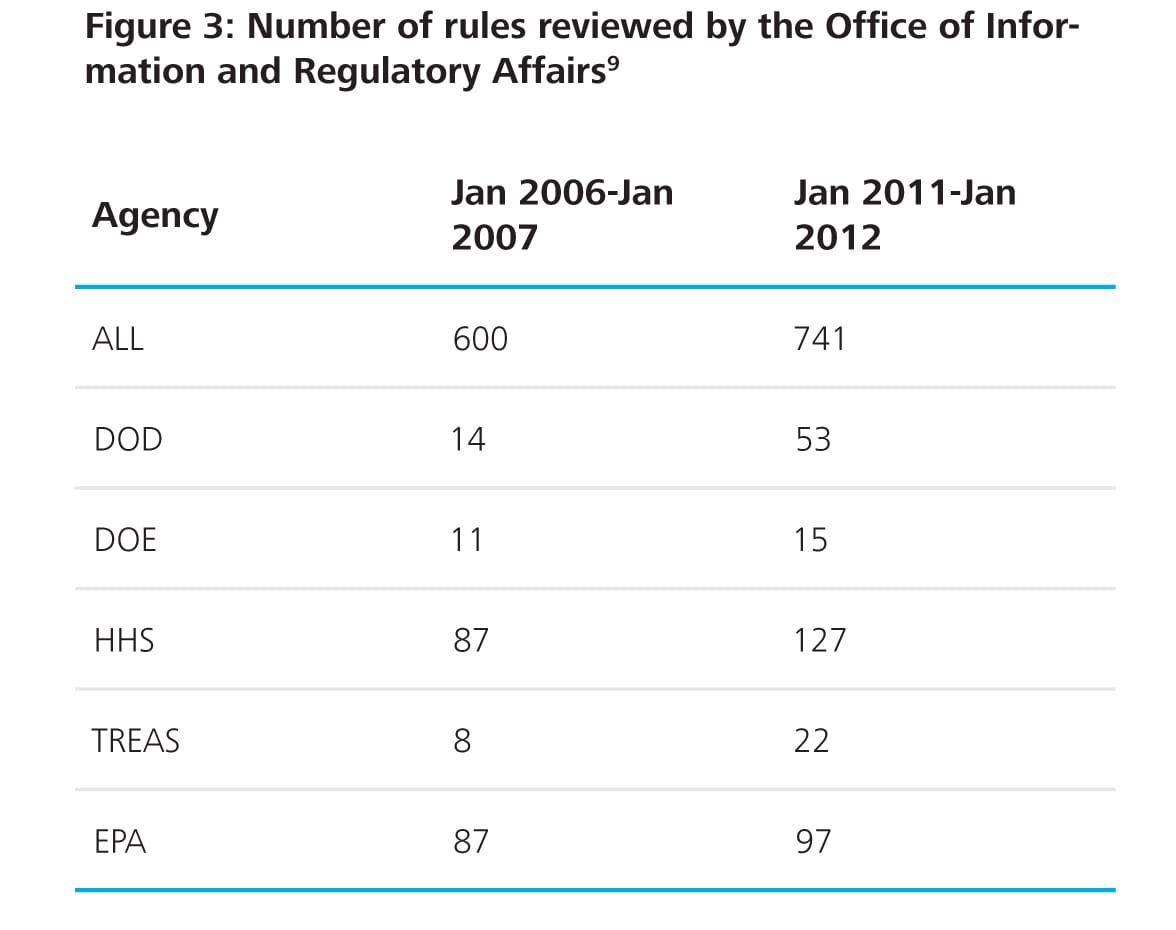

The government’s response to the recent financial crisis was largely aimed at offsetting the chances of another such disaster, most notably with regard to the passage of the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act. To date, the Commodity Futures Trading Commission has issued 40 final rules related to Dodd-Frank legislation alone.8 Meanwhile, government has become more active in regulating other areas, particularly healthcare, energy, and defense, reversing the de-regulatory trend. Evidence of this trend can be seen in the Obama administration’s requirement for doubling fuel efficiency standards by 2025. While government clearly sees re-regulation as part of the solution to prevent future crises, it should also avoid taking unilateral regulations that unduly harm business and damage economic growth. Both sides have an interest in partnering to develop smarter regulations.

See endnote 9

Innovation

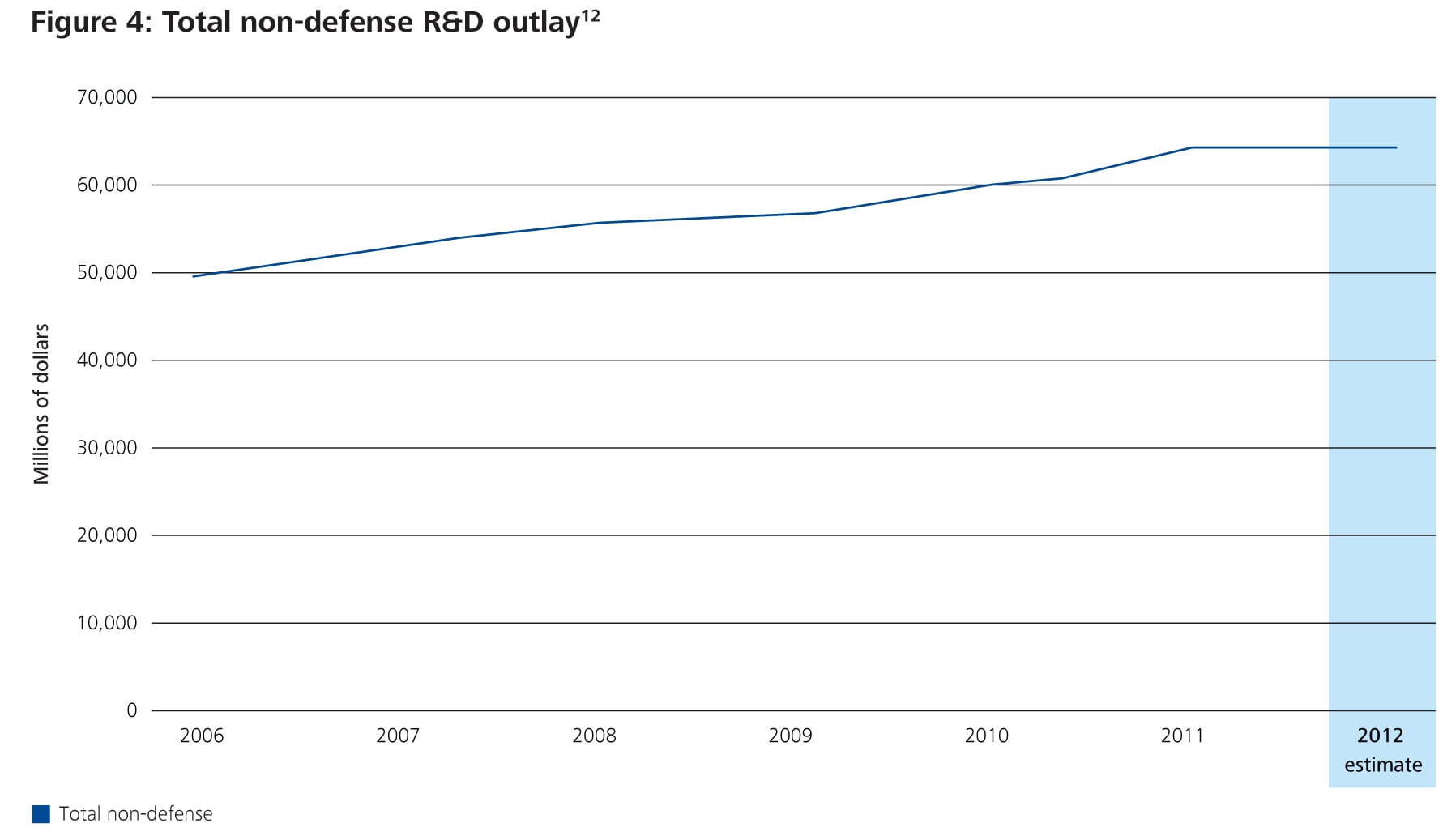

The federal government is increasingly turning to innovation as a means to improve services and engage more effectively with consumers. In recent years, more than 28 federal innovation offices and programs have been created, and many agencies have developed programs specifically focused on promoting innovation within the government.10 According to data from the Office of Management and Budget (OMB), the government has backed that commitment with consistent increases in R&D spending for non-defense, energy, and health sectors over the past four years.11 Innovation is also seen as a way for government to “do more with less” by adopting new technologies or dramatically changing its existing operating models. Government is increasingly looking to partner with and learn from business on how to innovate more effectively, and may represent a new market for business innovations.

See endnote 12

Lessons learned: What works and what doesn’t

The current environment calls for broader thinking about all that public-private partnership can really achieve beyond traditional PPP investment structures. It is important to realize that PPPs are not one-size-fits-all. There is a range of PPP models that can work in different contexts. Important to selecting the right model is to carefully evaluate the need. Selecting the wrong model can unnecessarily increase the chances of failure. Here are a few models that have already been shown to work.

- Compete—When business or multiple agencies within the government can approach the same problems with new solutions, competition can improve programs and spread innovative ideas while cutting costs. This may involve opening programs and services historically owned by one government agency or jurisdiction to competition, and may even require divesting programs entirely when it is clear that the private sector can more effectively and efficiently deliver services. Some entrepreneurial thinkers within government and industry are already fostering healthy competition between sectors. The “Mayor’s Challenge,” led by Bloomberg Philanthropies, encourages local leaders to compete with each other to solve national challenges and receive funding for the boldest ideas.13 Combining managed competition and gain sharing, the city of Tulsa fostered competition between city workers and private sector contractors by inviting them to bid on projects for Tulsa City Hall. Tulsa’s public maintenance staff won the contract and identified more than $100,000 in incremental cost savings, beyond reductions outlined in their initial bid. Engaging city workers in city solutions through a competitive bid process for projects enabled Tulsa to effectively leverage employees’ insights and capture cost savings.

- Engage—When solving problems that impact multiple, dispersed actors, business and government can form relationships and solicit new ideas even before legislative and regulatory processes take shape. Business and government’s collaboration to address foodborne illness regulation is a case in point. One in six Americans suffers from foodborne illnesses annually.14 Plus, food recalls can cost companies millions of dollars and take a significant toll on brand value. In order to foster foodborne illness prevention and food safety, the FDA is coordinating with other government agencies, the food industry, and non-US governments in the design and implementation of the Food Safety Modernization Act. Through this collaborative reform effort, the FDA aspires to create a cohesive, practical, and efficient food safety system.15

- Incubate—When new ideas require significant risk-taking but have transformational potential, government and business can work together to test and incubate ideas that cut across various agencies and/or commercial industries. One example of the power of public-private partnerships to test and incubate promising ideas was NASA’s 2010 OpenStack project,16 launched with the goal of significantly expanding cloud computing services. NASA launched the project in collaboration with Rackspace, a cloud computing company. Rackspace contributed its cloud files and servers service to the OpenStack project, while NASA provided its Nebula architecture and experience in building large-scale cloud platforms. Both NASA and Rackspace shared a similar vision for embracing open source and both reduced project risks by contributing their own assets. Through their collaboration, OpenStack has grown to become a global software community of developers aiming to create and offer cloud-computing services to virtually any organization on standard hardware.17

- Share—When the relationships between regulators and those they regulate aren’t at stake, government and business should actively encourage data sharing, communication and external rotation among their employees to glean knowledge, keep track of trends, and grow tangible skills. While some businesses may believe that they have little to learn from government, this perspective is slowly changing, particularly given government’s enhanced regulatory role. For example, after Hurricane Katrina, private sector companies were often cited as having advanced planning systems that allowed them to respond in ways that outpaced government support in some areas. As the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) began to realize the changing, more important role of the private sector in disaster response and recovery, it pursued an initiative to include the private sector in federal response and recovery efforts. FEMA initiated a partnership to invite private sector executives drawn from a wide range of sectors to participate in three-month rotations at FEMA headquarters focused on issues of national security and preparedness. Through this initiative, FEMA and the private sector are collaborating to develop joint solutions that enhance the quality of disaster relief efforts and improve information sharing and collection.18

- Cooperate—When government and business—and even government, business, and the social sector—can collaborate in ways that align their core competencies and strengths, there can be significant benefits for all involved. In the area of social and economic impact, a new model called Strategic Social Partnerships is emerging to characterize business, government, and social sector collaboration on issues of sustainability, human rights, and cross-sector knowledge sharing. In order to address the adverse implications of toxic cookstove smoke in the developing world, the Department of State launched The Global Alliance for Clean Cookstoves. This alliance is an innovative public-private partnership led by the United Nations Foundation that aims to save lives, improve livelihoods, empower women, and combat climate change by creating a thriving global market for clean and efficient household cooking solutions. The alliance’s mission is for 100 million homes to use clean and efficient stoves and fuels by 2020.19 This effort has become one of the Department of State’s flagship initiatives under the Secretary’s Global Partnership Initiative.20 Through the Global Alliance for Clean Cookstoves, the government seeks to work with public, private, and non-profit partners to address problems of global scale.21

Looking ahead

So what will the future look like? The socioeconomic forces driving change today are expected to evolve into the future, requiring practical mechanisms to harness the opportunities presented by PPPs. The broad PPP strategies above, while just starting to occur today, will likely become a standard component of government and business strategy over the next decade as the two sides work to address their complex challenges. Effective organizations understand the potential that partnership strategies offer not only to solve national challenges, but also to create opportunities for economic growth and business success. But to make partnerships work, they should match the partnership model to the appropriate context. Partnership opportunities can be identified and initiated in either the public or private sector, and to achieve their goals both organizations should:

- Develop a “partnership culture”: Create the type of environment that encourages and rewards employees to constantly be on the lookout for new opportunities to engage and collaborate across sectors.

- Include the identification of new government challenges and the corresponding PPP opportunities on the CXO agenda. Measure activity to encourage managers to think about the potential in addition to other private sector business development initiatives.

- Assign a senior leader to oversee PPP efforts: Appoint a leader who has a long-term vision of the project and can take the steps needed to break down barriers and win the confidence of the staff.

- Define a clear point of contact and mechanism for tracking PPP efforts: Often, PPP efforts are hampered by confusion over what is being done in other parts of the organization, which can result in turf battles or a lack of consistent messaging.

- Address legal or other organizational aspects of partnerships: Partners should be clear about what each party can or cannot do legally and about what each party brings to the table.

- Reach out to potential PPP partners early in the process. Use the outreach as an opportunity to jointly diagnose the problem, create the rationale for the PPP, gain consensus on the vision, identify potential barriers, and structure the activities which the PPP will undertake.

- Select the appropriate model: The wrong approach can waste resources and, at worst, destroy value. The focus should be on understanding the context and the specific problem that needs to be solved.

By finding ways to balance their respective strengths and experiences, government and business can form effective partnerships to help resolve critical challenges, generate economic growth, and realize cost savings for the government. Some have estimated potential savings benefits of 20 to 50 percent.22 But PPPs are complex arrangements, and the difficulties of making them work should not be underestimated. Achievement of goals will likely depend on each side recognizing where it adds the most value and gains the greatest benefits: for example, when government engages business interests where it can now provide only limited financial resources; when business leaders proactively leverage government resources and guiding actions to better support the competitive needs of the United States; or when both public and private sectors partner with NGOs and the academic community to explore new realms and markets with innovative approaches. The door to new partnering opportunities is beginning to open even wider. Who will be the first to take full advantage of these opportunities?

My take

Bill Eggers, Global Director, Public Sector Industry, Deloitte Research, Deloitte Services LP

We are experiencing a dramatic change in how societal challenges are tackled—a shift away from a government-dominated model to one in which governments are just one problem-solver among many. Over the last decade, a number of new players have entered the arena and operate within what we call a “solution economy.” Through dynamic partnerships, these innovators are closing the widening gap between what governments provide and what citizens want. This new approach intends stronger results, lower costs, and the high hope we have for public innovation in an era of fiscal constraints and unmet needs.

Paul Macmillan and I explore this collaborative economy in our forthcoming book, Solution Revolution: How Business, Government, and Social Enterprises Are Teaming Up to Solve Society’s Toughest Problems. We argue that public sector problems transcend the domain of traditional government and require a broad, collaborative approach.

As discussed in Partnerships for the Future, the rigid silos of traditional industry, government, and other public institutions often run directly against the ethos of how problems are being effectively addressed today. Partnerships among private, nonprofit, and public enterprises are critical to developing effective, multidimensional solutions.

Consider waste management, a problem the affects citizens in the developed and developing world alike. Eight thousand miles away in India, Parag Gupta, a social entrepreneur we profile in our book, chose to test a collaborative business model to clean up the 40 million tons of garbage his country produces each year. Gupta established Waste Ventures, working with international donor institutions and social impact investors to engage a segment of the Indian population known as “trash pickers.” For Gupta, it was quickly apparent that acting in isolation or through a government-only paradigm would be a path to failure. Instead, he worked with the “trash pickers,” local NGOs, and government officials to build an ecosystem to clean up some of India’s worst garbage-plagued urban areas.

Going forward, governments should look to business and social entrepreneurs as important partners in solving the world’s greatest problems. The solution economy thrives in this environment where a cadre of actors—from governments to business, from social investors to ambitious entrepreneurs—work in partnership to create positive change.