Crossing the chasm: From operator to strategist has been saved

Crossing the chasm: From operator to strategist A CFO Insights article

11 May 2011

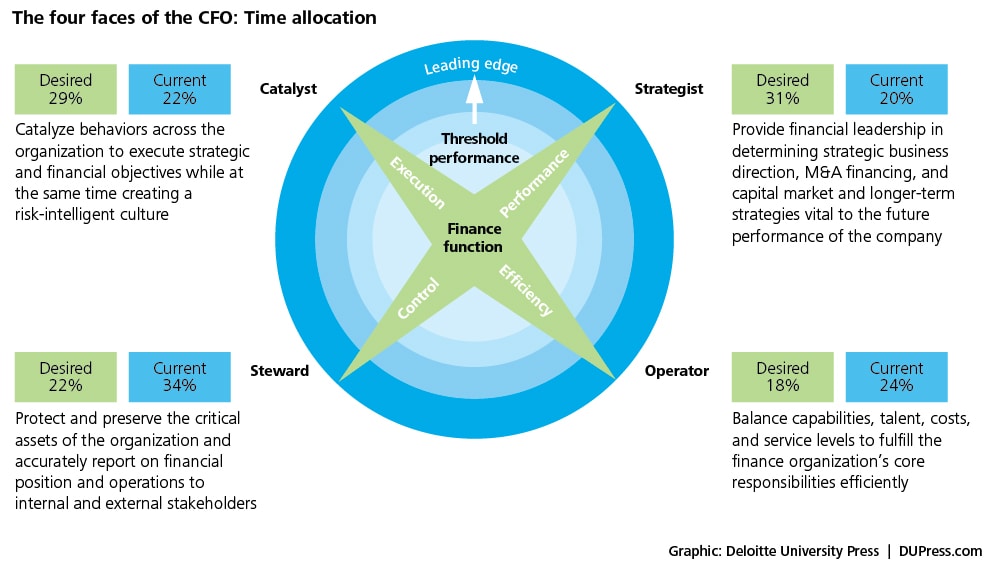

Many CFOs start out as operators in the finance role and as stewards addressing controls and compliance—roles that often continue to dominate throughout their tenures. Here are some ways that CFOs can cross the chasm to a more strategic role.

Many CFOs want to partner with the CEO as a key strategist and catalyst for change. Yet, when we ask CFOs where they spend their time, most respond that they fall considerably short of this goal. In fact, Deloitte’s CFO Signals survey found that, while CFOs desire to spend 60 percent of their time as a strategist or catalyst, in reality they average only 42 percent of their time in these roles.1

Many CFOs want to partner with the CEO as a key strategist and catalyst for change. Yet, when we ask CFOs where they spend their time, most respond that they fall considerably short of this goal. In fact, Deloitte’s CFO Signals survey found that, while CFOs desire to spend 60 percent of their time as a strategist or catalyst, in reality they average only 42 percent of their time in these roles.1

This disconnect is even more pronounced in our work with newly appointed CFOs. In those cases, we often find the chasm between CFOs’ aspirations for their first 180 days—and often their first year—and their actual time allocation to be even larger. Priorities in the first 180 days typically require repair of finance operations, information systems, and controls. Consequently, CFOs start out as operators in the finance role and as stewards addressing controls and compliance—roles that often continue to dominate throughout their tenures, according to CFO Signals.

This obviously isn’t what CFOs want, nor is it what boards and CEOs have in mind. When we ask why a CFO was hired, we often hear that the company needs a more strategic CFO, someone to partner with key business leaders in framing strategy. In addition, with capital a key strategic asset, boards and CEOs want a finance chief who can align business and financial strategy.

So why are many CFOs unable to cross the chasm to make a strategic impact? There are a number of plausible reasons. One may be that some CFOs prefer to stick to what they are most comfortable with—leveraging their accounting and finance expertise and running finance operations instead of advancing changes to the broader organization and driving strategy. Indeed, there may be some truth to the view that many CFOs like to stick with what they are most comfortable. Another hypothesis might be that there are not enough opportunities to act as strategists and catalysts, so CFOs spend their time in other roles. However, this does not seem consistent with what CEOs and boards tell us about their expectations of CFOs.

Instead, based on our experience with current and future CFOs, we propose that many fail to cross the chasm because their finance organizations may not have the right mix of talent or capacity to adequately free them from their operator and steward roles. For every CFO, there is a fundamental trade-off between available time and talent. If you have the right talent for supporting roles, it can free you to be more strategic. If you have enough trusted people inside or outside the company who can be accessed in a timely way, you can focus on the more strategic aspects of the role. Moreover, speed counts. Our work with CFOs finds that the choices they make quickly regarding their staff is a key determinant in successfully crossing the chasm.

Crossing the chasm—five considerations

Whether it is in their first 180 days or throughout their careers, today’s CFOs confront a complex array of issues. It is understandable how operator demands (outsourcing, capital budgeting, tax planning, upgrading finance talent, etc.) and steward demands (connecting to analysts and investors, implementing risk management systems, establishing strong controls, etc.) can monopolize a CFO’s time. After all, it is easy to allow the urgent matters inherent in those roles to dominate the agenda. But embracing catalyst demands (creating an enterprise value focus, driving more fact-based decision making, establishing new performance metrics, etc.) and strategist demands (M&A due diligence, reframing capital structure, transforming legal-entity structures, etc.) is as important to the future of the organization as to the CFO’s own. And based on our experiences working with CFOs, we find the following approach helpful in enabling CFOs to cross the chasm:

- Classify initiatives by importance and urgency

- Identify your operator and steward wingman

- Define your organization structure to meet your needs

- Delegate quickly

- Build a bench and execute a talent agenda that gets you to your goals

Classify initiatives by importance and urgency

When a CFO initially takes the role, he or she is typically confronted by multiple demands across the four faces of the CFO. In our work with newly appointed CFOs, we have found it useful to have CFOs consider initiatives beyond what they are currently doing and sort them into the urgent and the important. Separating priorities into these two buckets is a useful exercise since it helps CFOs decide where they should commit their time over the first year and avoid expending time on less important issues.

Identify your operator and steward wingman

If CFOs are to successfully focus on their strategist and catalyst roles, they need a wingman to protect their flanks and oversee the basic finance function. For many CFOs—especially CFOs who do not come from accounting backgrounds—this person may be their controller or chief accounting officer. In larger organizations, it may be a chief of staff to the CFO or even a divisional CFO. We have found CFOs are often reluctant to appoint this person the deputy CFO, however. Instead, the allocation of responsibilities is often more informal to avoid creating a succession expectation. But as the CFO role becomes more strategic, it is imperative for CFOs to have a trusted resource to ensure that basic finance function activities work smoothly.

Define an organization structure to meet the CFO’s needs

Having the right organization to support the CFO’s needs is another way to free up time. When we work with newly appointed CFOs, we find that they sometimes rethink the reporting structure they inherit. One consideration is deciding how many direct reports is optimal; another is analyzing how the leadership team should function. Indeed, sometimes reducing the number of direct reports frees up time to focus on more strategic relationships with key stakeholders. In addition, removing or reassigning individuals who are high maintenance or drain energy can often free up time to attend to more important things.

In defining the organization structure, however, it is important not to think about how the organization meets current needs, but rather how it will meet future needs. Is the company expanding internationally? If so, will it need regional CFOs? Can the current structure migrate easily to accommodate geographic expansion or expansion in general? Thinking one step ahead and building flexibility into the organization can avoid costly restructuring later. Most important, every CFO should ask, “Does the organization meet ‘my’ future needs and likely role?”

Delegate quickly

Another key to crossing the chasm is to delegate quickly to staff who can execute key priorities. For major initiatives, it is critical for a CFO to have staff who are accountable for leading each initiative on his or her behalf. Establishing who will drive the CFO’s key initiatives forward further helps free up time to focus on strategist and catalyst roles.

Build the bench for the future

One common challenge we find CFOs grapple with when they transition into the role is the lack of a deep bench in their finance organizations. Indeed, there may not even be enough strength or “stars” in a CFO’s direct reports. If the finance organization’s talent is insufficient, then the CFO is likely to find himself or herself focused on operator and steward issues. Thus, it’s often imperative to frame a talent agenda that develops staff capabilities and defines clear succession plans. One piece of talent vital to this agenda is having a strong HR organization. If this is not the case, the CFO needs to get the requisite internal or external support to hire, onboard, and rebuild the organization.

Time is a key perishable and non-recoverable resource for CFOs. To become more strategic, CFOs need to have a clear idea of how they want to spend their time and build the requisite organization to allow them to attend to the important. And if they take the steps to separate the urgent from the important, identify a wingman, execute quickly, and rebuild their finance organization for the present and the future, CFOs can effectively cross the chasm from operator and steward to strategist and catalyst.

To learn more about how CFOs successfully navigate transitions, see Taking the reins: Managing CFO transitions.2

Time is a key perishable and non-recoverable resource for CFOs. To become more strategic, CFOs need to have a clear idea of how they want to spend their time and build the requisite organization to allow them to attend to the important.