A pragmatic pathway for redefining work The beaten path won't get you there

47 minute

03 October 2019

Organizations face a multifaceted future unsettled by new technologies and flexible business models. And that offers the opportunity to redefine work to move toward more creative, meaningful jobs—and more bottom-line value.

Introduction: Big things from smart moves

Everywhere Amy looked, there were signs the firm needed to change. With the rapid acceleration of self-service technologies and online alternatives, it was becoming harder for the regional brokerage to keep up. They’d survived the recession, but they were still at risk of disruption. Despite trying to adopt new technologies and modernizing the back-end, streamlining operations seemed inadequate against the existential threat of irrelevance.

Learn more

Read more from the Future of Work collection

Subscribe to receive updates from the Center for the Edge

Download the Deloitte Insights and Dow Jones app

From top to bottom, people were concerned, and Amy—the firm’s chief people officer—found herself fielding questions seemingly every day about everything from how automation would affect their small-town branch employees to where the company would find the talent it needed to embrace new technologies to how the firm could continue to satisfy an increasingly diverse and divergent customer base. Meanwhile, she wondered how her organization could better support a geographically and demographically distributed workforce through a rapidly changing world that asked more of them as employees and put stress on the communities they served.

When the CTO announced a plan to switch to a new set of office tools, Amy saw an opening to reset how people thought about their work, their colleagues, their technology, and the HR organization. What if she could use this broad technology change as a catalyst to address the larger problems: a workforce unprepared for the future and a “well-run” business vulnerable to disruption?

Toward a multifaceted future

The future of work is more than emerging tech churning through decision trees at lightning speeds or inexhaustibly plowing through routine tasks. It’s more than humans and machines collaborating in an augmented environment or a billion freelancers logging in from around the globe to do the work of the firm.

Something is missing.

The future of work is potential—for expanding value and meaning. Emerging technologies and flexible business models and work arrangements offer an opportunity, largely unexplored, to create more and more value for the customer, the workforce and other stakeholders, and ultimately for the firm. That opportunity is to redefine the work itself, to shift the entire workforce’s focus away from the predefined and standardized tasks of today and onto creating new value around expanded work outcomes. For companies, the reward for tapping into that opportunity is the potential to get off a curve of diminishing returns and be better positioned for the future. For the workforce, the rewards are experiences and challenges that develop the skills and capabilities to stay relevant, as well as the connections and resources to make a greater impact on outcomes that matter.

The future of work is multifaceted. Many of the forces that will transform the work, the workforce, and the workplace—rapid technological, social, demographic, and environmental shifts—are already visible. Their impact will become more visible as the pace of change accelerates. Leaders and workers are feeling the mounting performance pressure caused by these shifts. Artificial intelligence, robots, and automation—not to mention more run-of-the-mill technology—is reshaping how today’s work gets done at various levels of the organization, in many cases eliminating the need for human workers to do tasks associated with particular outcomes. These same technologies can also open up interesting opportunities to redesign jobs around human-machine collaboration in ways that enhance human workers’ capacities or abilities.

Facing a relentless pace that shows no signs of slowing, leaders find themselves simultaneously facing both immediate pressures and longer-term threats and opportunities. They may well ask: How do we maintain a competitive advantage in that world, and what do we do next to move in the right direction?

For business leaders, the future of work needs to incorporate all of these opportunities: to streamline, to augment, and to redefine. Currently, the conversation feels heavily weighted on the first of these, with some pockets of interest and emerging use cases drawing attention to the second—humans enhanced by machines. In some ways, optimizing today’s work with emerging technologies is easy—it is an extension of the past few decades’ process redesign work and systems implementations, albeit with more potential for near-term efficiency and dependability gains.

This article focuses on the third opportunity: the opportunity to redefine work.1 The dramatic shifts create not just space but the imperative to reimagine what work should or could be. Our prior research has shown that clearly addressing the question opens up possibilities for creating a more expansive future. The crux of the answer is three shifts (see sidebar, “Redefining work: The three shifts”).2 Shifting the objective to broader value creation and refocusing the workforce on identifying and addressing unseen opportunities to create value can help companies build deeper relationships and more sustainable differentiation. And this sustained differentiation will help companies get on a curve of increasing returns.

An additional benefit of redefining work: The process itself can create value and meaning for workers and other stakeholders, leading to a virtuous cycle that ultimately creates more financial value for the company. This article suggests how companies can get started on the path of redefining work for this virtuous cycle.

Redefining work: The three shifts

Shift the objective of work from efficiency and cost savings to broader value creation—not just incremental but exponential value—by going after significant problems and opportunities.

Shift the focus of workers from executing routine tasks and processes to identifying and addressing unseen problems and opportunities. Let machines take on the tasks and processes that are truly repetitive so that people can be free to focus on what is not.

Shift the requirements of workers from specific skills (which quickly become obsolete) to enduring human capabilities, helping workers to learn faster and to better see and address previously unknown opportunities.

Importantly, companies have the opportunity to redefine work well beyond product development—they can look throughout the business and to service functions such as IT, HR, and finance as well. Indeed, this type of creative problem-solving work already happens in pockets across most organizations: People are working with processes, policies, and systems that don’t meet current needs, and doing nonroutine workarounds to serve customers. But such efforts are typically viewed as “above and beyond” or “under the radar,” and official work processes remain unchanged.

Redefining work is about the organization deliberately choosing to define work to be about addressing unseen opportunities to create new value. Making this choice ultimately implies changing everything: systems, practices, infrastructures. Fortunately, companies can get started without scrapping everything at once and beginning from scratch. A proof-of-concept targeted at the right issues can have a meaningful impact in the near term while the organization learns how to best redefine work for its needs.

In this article, we explore a pragmatic approach to begin making smart, targeted moves designed to get maximum impact—to build momentum, enthusiasm, and confidence in redefining work across the company, to accelerate performance, now and in the future. We look at what is required: what constitutes an opportunity, where to start, and how to get started.

Zoom out: What is the future of work, and how does it get done?

Before we delve deeper into this pragmatic approach, it is helpful to consider a vision of what work and organizations might look like in the future. If this is a journey worth taking, what is the destination?

Redefining work is about expanding our notion of work and work outcomes rather than treating them as static. It isn’t about taking the products and outcomes that are delivered today and achieving them in some other way. There will be new and different work to do in the future because there will be new and different problems to solve and new and different needs to address. Changing expectations and new solutions will surely make much of today’s work obsolete.

To better understand the vision, consider the two major trends driving the need to move beyond the status quo and redefine work.

First, we’re moving into a world of mounting performance pressure in which no one will settle for steadily diminishing returns. The Shift Index data affirms the decades-long, cross-sector deterioration of corporate performance and the concurrent increase in competitive intensity and decreasing stability of market leadership.3 Companies will have to deliver more than the incremental or diminishing performance improvement that is available from optimizing current work.

Second, customers are becoming more powerful. Increased visibility and access to a wider array of options changes how customers perceive value, with customers increasingly expecting products and services that are tailored to their unique needs and preferences. Companies can no longer orient around processes designed to deliver standardized products and services.

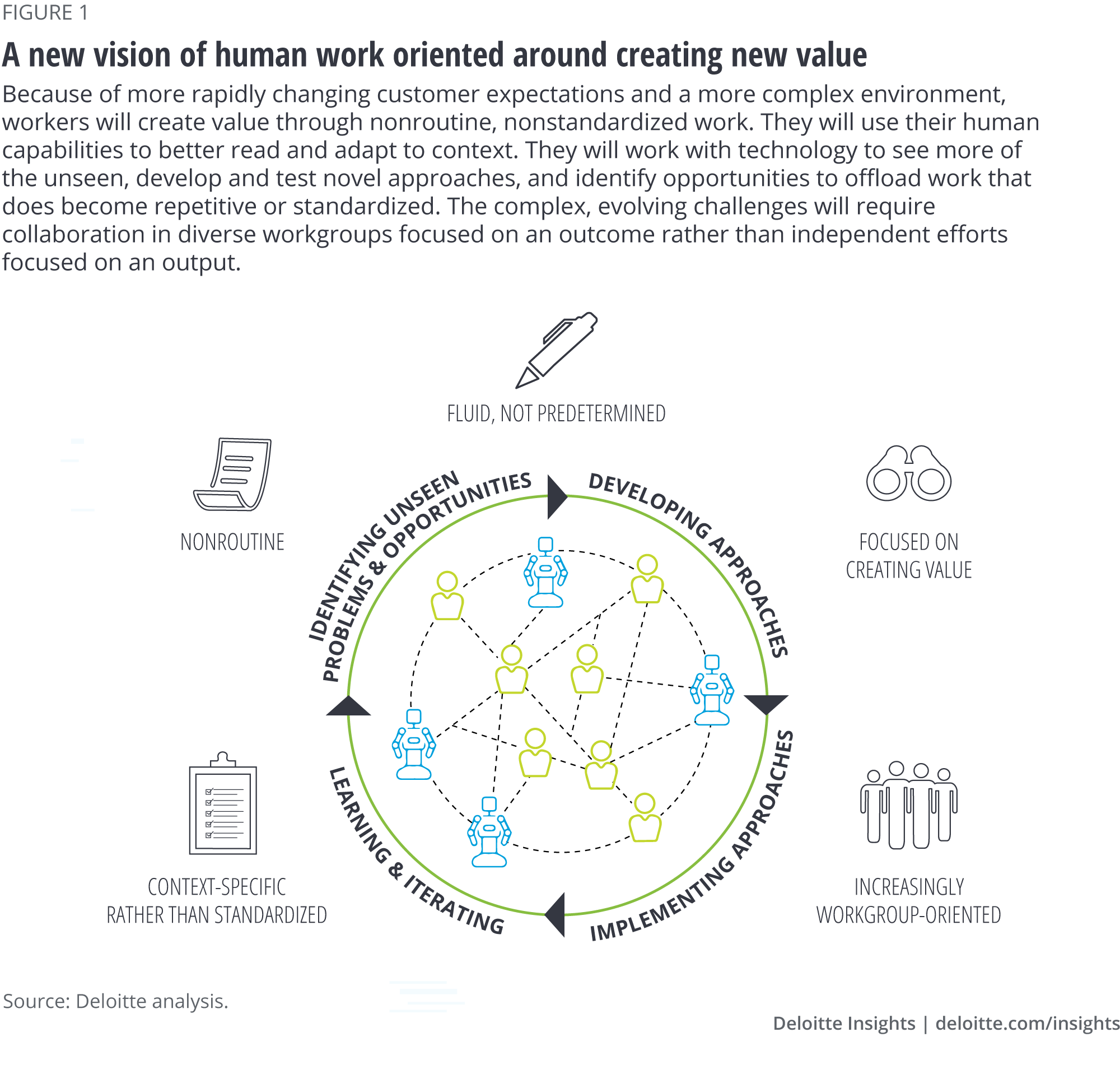

These two trends have direct implications for the future work of creating new value (figure 1).

This work is the platform to shift from the old world of scalable efficiency—in which organizations, systems, and processes were oriented around predictability—to a future state of scalable learning, in which conditions, tools, and requirements change more rapidly and organizations, systems, and practices must reorient around learning, adapting, and shaping. Our prior research provides evidence4 that workgroups5—and the business practices, management practices, and structures that guide and connect them—will become increasingly central to forward-looking organizations. Participation in knowledge flows will be critical to remaining competitive and innovative for companies and individuals.

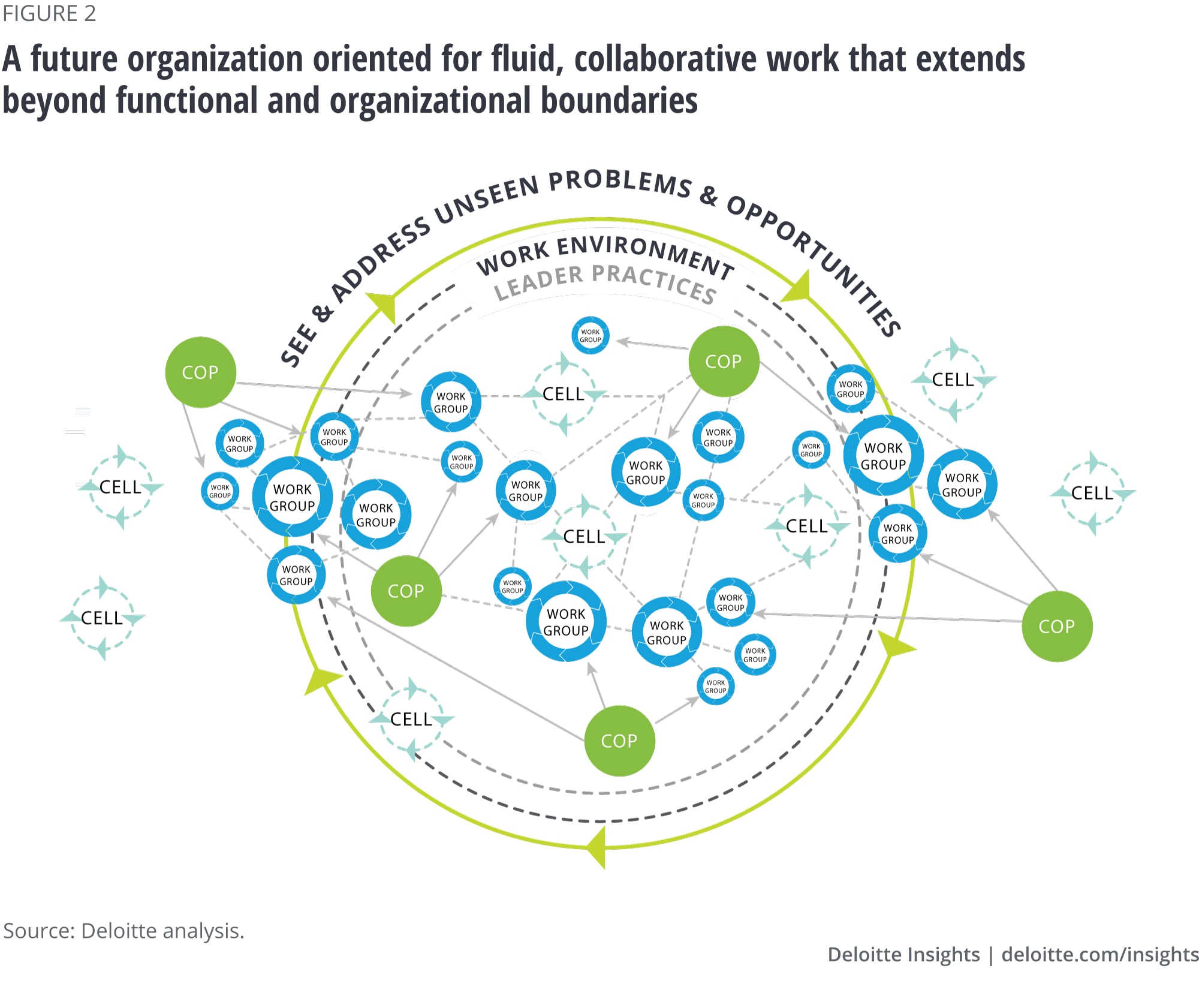

Redefined work, then, implies a different type of organization to support it; figure 2 illustrates one possible interpretation. The organization is flatter, frontline workers are the engines of new value creation, and the boundaries between the organization and ecosystem are blurred. New physical and digital layers enable different ways to cocreate and communicate.

This is the destination—what the future could look like if leaders choose to redefine work.

The approach: Big impact, smart moves

Most companies don’t look like this today. How, then, to get there?

Redefining work implies changing everything; meanwhile, most organizations are under mounting pressure and have immediate pain and needs now, in the present. A smart moves approach can quickly demonstrate maximum impact, with minimal investment. Redefining work may address near-term pressures or complement other efforts to do so, but the focus is on making an impact. This approach is built around using a targeted proof-of-concept to create momentum, support, and the organizational capacity to redefine work.

Small doesn’t mean insignificant or incremental. What small means is avoiding the temptation to spin up a large change initiative necessitating months of planning, alignment, meetings (and meetings and meetings), and road maps for organizationwide transformation prior to creating, or even understanding, what the future of work might be in your organization. The rate of change, the needs of the customer and the workforce, the opportunities for leveraging emerging technology—all will manifest and evolve differently in different organizations. The goal of small, smart moves—in addition to demonstrating a significant impact—is for the organization to learn as quickly as possible how to fundamentally redefine its work (change the objectives, shift expectations, and build support) to succeed in a future of rapidly changing needs and requirements.

Why not just go with big moves instead? First, as we discuss in prior research,6 many major change initiatives fail just by the nature of how organizations react to large-scale change. Few organizations are equipped to handle the lag between making a big investment and seeing results or achieving scale, and leaders often prematurely kill the initiative either indirectly or through an official mechanism. Second, there is a danger in creating a big program that puts a stamp or slogan of Redefine Work on everything without actually changing the work being done. This tends to be the fate of many well-considered, much-needed programs and initiatives everywhere. Consider the many companies that excitedly “implemented” agile or “went digital” with highly publicized initiatives that generated a lot of buzz inside and outside the organization, but failed to get beneath the surface of the work, the how and what people are doing. In a similar vein, implementing technologies, even exciting, emerging ones, can free up capacity, but they don’t alone make for a new or more successful type of organization. When the program inevitably fails to deliver the desired results, workers and management can become cynical.

The smart moves approach is designed to focus the organization less on fresh language than on doing and learning through doing ‘how to work’ differently. The program involves frontline employees organized into workgroups to address particular issues, learning rapidly through action. We will delve into key aspects of the approach in the remainder of the article.

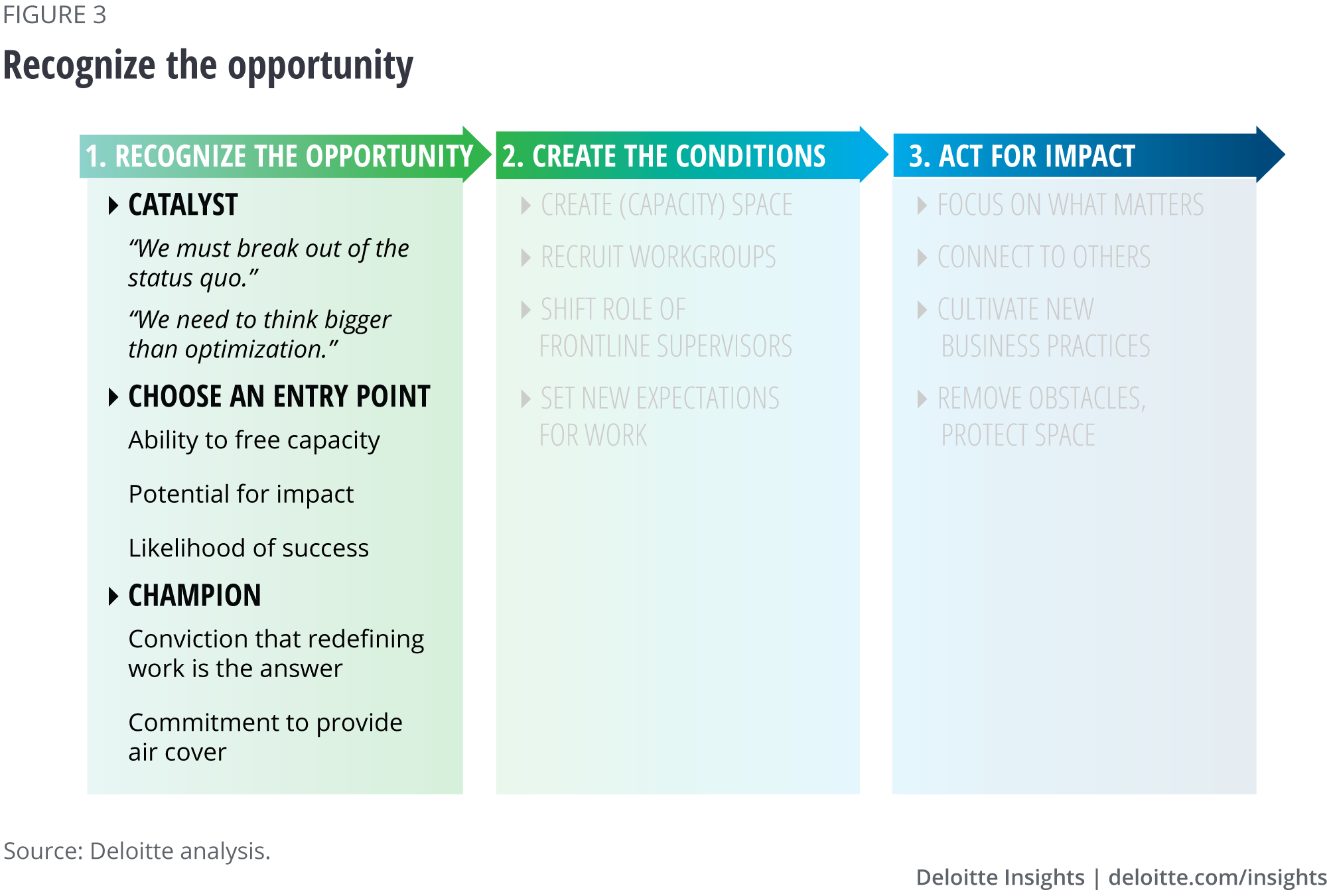

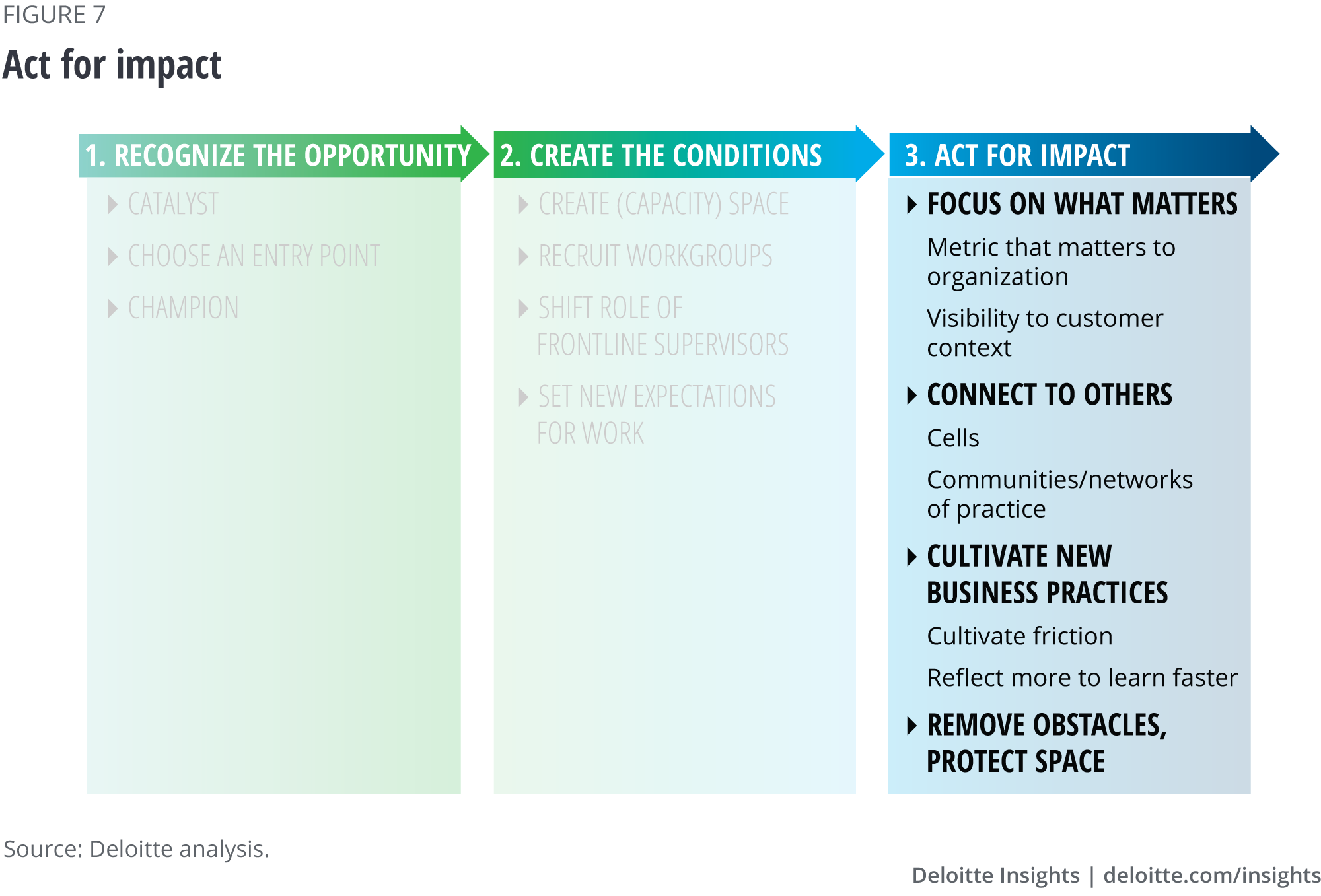

Recognize, create, act

Recognize the opportunity. Too often pilot projects either flounder for lack of support or are so marginalized that the results can be dismissed as irrelevant to the greater organization. The goal of recognize the opportunity is to identify the entry point in the organization at which a pilot for redefining work is most likely to succeed and where the impact will be most relevant to generate further momentum.

Create the conditions. The goal is to move fast, laying the groundwork to support breaking from the status quo and meaningfully refocusing on value creation without getting bogged down in all the possible plans and support structures of large transformation. Create the conditions establishes, and redefines work for, a small set of workgroups that will form the proof-of-concept.

Act for impact. The goal is to support the pilot workgroups as they learn how to better address problems, with an eye toward a deeper understanding of the customer. As the workgroups gain confidence, new business practices7 can help them get better at identifying and addressing unseen opportunities with greater potential, and leader practices and the work environment can evolve to help sustain motivation and impact.

As the workgroups begin demonstrating results, they generate momentum, attract attention, and draw others in. New workgroups may form or spin off based on newly identified opportunities, as well as growing interest in the new way of working. The organization starts to learn what it will take to redefine work, how and where to redefine work next, and at what scale.

Recognize the opportunity: Smart moves mean the right catalyst with the right champion in the right part of the organization

Beginning the journey to redefine work requires, first, an opening to reconsider the fundamental work of some part of the organization. A catalyst calls into question the status quo, points toward refocusing on value, and creates urgency to act. A catalyst alone isn’t enough, however. A prerequisite for a successful proof-of-concept is having a champion who believes redefining work is the answer and has enough power and commitment to sponsor the pilot at an entry point where it can demonstrate results and motivate others.

Catalyst: Urgency to move beyond the status quo

Most leaders face multiple challenges, big and small, at any given time. Why would or should they take on the task of trying to redefine work? It is a choice. Any organizational challenge that creates a compelling and urgent argument against the status quo has the potential to catalyze redefining work. However, if there isn’t a felt need to do something fundamentally different, and an urgency to act on it, even a small pilot is a waste of time. The catalyst is what grabs your attention; redefining work is what shifts you from fear to opportunity.

The nature of the challenge also matters. If the urgent issues a company faces are not at least partially aligned to derive near-term benefits from redefining work, the proof-of-concept may derail. Ideally, the challenge is directly addressable by refocusing on new value creation and expanded work outcomes.8 Some challenges may be addressed more through the positive externalities that redefining work creates, such as greater employee motivation and engagement, increased on-the-job learning and development to close specific skills and capabilities gaps, or even improved relations with the workforce and community stakeholders. Urgent issues that seem to require immediate resolution through optimization or controls are ineffective catalysts, even if they might benefit from collaborative problem-solving.

It’s useful to consider some of the typical issues large companies are facing and whether they could catalyze an effort to redefine work. For each situation, ask:

- Do we clearly need to break from the status quo?

- Is it urgent to act now?

- Is it clear we need to think more expansively than optimization—for example, creating value and meaning?

- Is there potential to create capacity? For instance, could a pilot group of frontline workers be freed from their current day-to-day tasks to do redefined work as their full-time job?

Market pressures often create a sense of threat and increased fear. Fear tends to be destructive; it can drive people into a narrow, zero-sum mindset that limits the ability to see other options or pursue opportunities. However, in the short term, fear does focus attention and can increase the organizational appetite for risk. A general understanding that current approaches aren’t working can generate greater openness to doing something new.

A range of factors can create urgency, including declining market share or being disrupted by an emerging player. Redefining work can provide a competitive marketplace edge by creating more customer value as well as more value for internal customers, such as sales and the workers themselves. For example, consider an organization losing customers as a result of poor service from the customer service center. Meanwhile, the service center agents are stressed and dissatisfied because they are unable to address customers' diverse needs—and they are leaving for other jobs as a result. In such a situation, implementing more controls isn't likely to improve quality.

Skills gaps can spark interest in redefining work, out of necessity. The useful life of a skill has rapidly declined even as many organizations face critical skill shortages. Redefining work can help people learn faster, strengthening workers’ human capabilities in the work itself, and tapping into intrinsic motivations to pick up and apply new skills.

Engaging people can ameliorate concerns about planned automation threatening frontline jobs, news of which can generate unwanted attrition, poor morale, and an inability to hire needed talent.

Technology-driven change, with attendant discussions of work outputs and processes, may present an opening to shake up the status quo. Without some sense of urgency, however (perhaps in combination with mounting pressures), you risk getting slowed down and distracted by plans for change and the need for alignment.

Many organizations are engaged in some form of automation using robotic process automation (RPA), AI, or robotics. The rationale may be to free up capacity, either to support growth without increasing headcount or to cut costs by reducing headcount. The latter case creates an opportunity and capacity for radically rethinking the potential value that part of the organization could deliver, beyond the current—soon-to-be-automated—work outputs. It requires leadership commitment to not reduce force immediately and to provide some space for workers to begin drawing on their experiential knowledge of the customer, information and material flows, the environment, and the institution. As one health care back-office processor discovered, in this type of scenario, frontline workers can start by working together to automate current tasks as a way of developing the ability to work in a more creative, collaborative way. Because the automation was happening in waves across the organization rather than all at once, this was a manageable and useful way for the company to develop new skills, capabilities, and confidence in workers who had been focused narrowly on tasks.9 As the automation frees up the frontline’s capacity, their work can be redefined and focused on creating new value.

Large technology implementations present an opportunity to examine current work, what it delivers to the internal customer or other partners, and whether it should be done at all. By asking how it supports value for the external customer and how data flows or relationships around the current work could be used to create or support additional customer value, a technology implementation can be a catalyst to expand work outcomes rather than just gain efficiencies—if it is accompanied by urgency. This is what ATB Financial did when leaders combined the existential threat of disruption with the companywide implementation of a new productivity suite to push every employee to reevaluate their work—what, why, and how—and change it. People were guided to think critically, to work with others, and to question how the work they were doing created value for the customer or supported an internal customer in being more customer-centric.10

Other types of organizational change, such as integrated value chain or merger, create an opportunity to reconsider what types of value can be delivered by diverse groups (designers, sourcing specialists, factory workers, buyers, marketers, salespeople, etc.) and could be used to think more expansively about work outcomes in the future. The larger change is likely to draw away the resources, attention, and capacity needed to redefine work. Even if a pilot succeeds for a small group, the results would likely get little attention in an organization undergoing massive change.

So, what is likely to get attention? Compelling opportunities, so long as the organization pursues them swiftly. That’s often a challenge: For many companies, status quo processes and management systems mean that by the time they mobilize a team and align stakeholders, the opportunity has passed. The frustration caused by this type of compelling but elusive opportunity can provide the opening to redefine work—if the potential of the opportunity is framed around tangible impacts to the customers, workforce, and company.11 The inherently opportunity-focused catalyst can make it easier for workers and managers to refocus their objectives. At the same time, if leaders have identified an opportunity, they can skip many of the preliminary smart, small moves. The part of the organization that can pursue the opportunity should move to immediately address it with a few workgroups using new business practices, as we’ve discussed in greater detail in Moving from best to better and better.12

The other possibility is that the organization is concerned with a less specific issue that might nonetheless be top-of-mind for leaders and the market. This might include heightened attention to the workforce impact from future of work, or an anticlimactic agile slump that begs for supporting moves, and changing work to build on the agile investment to be better positioned and prepared for the future.

Champion: Conviction and power to redefine work

The right champion is a leader who believes that redefining work can address the catalyst. The champion understands the opportunity to redefine work, commits to it, communicates it, and covers for it.

Redefining what work is means shifting objectives and how success is measured. It can change dependencies, reporting, and decision-making. As always, challenging the status quo can trigger extreme opposition from those most invested in it. For those reasons, the champion should be the CEO or another C-level executive—someone with organizational power and influence.

The champion communicates conviction in redefining work. While it may not come to fruition immediately, a credible and compelling vision that focuses on opportunities and deliberately addresses the zero-sum mindset can offset fear and any consequent resistance. It can also help guide leaders making near-term decisions about investments, technology, and the workforce to be guided by the longer vision. Communicating a vision about the opportunity and benefits of redefining work for the company is important, especially if there’s reason to believe that the workforce and other stakeholders are losing confidence in the company’s prospects for the future.

Perhaps more important, the champion should make clear the near-term opportunities and benefits for frontline workers directly involved in the workgroups program. This may seem obvious, but leaders too often fail to communicate a vision tied to people’s unarticulated concerns. Consider the example of a head of finance who wanted to modernize the department, including using RPA for data entry and reconciliation tasks so that the finance staff could have the capacity to provide more in-depth financial analysis to help the business respond more quickly to market opportunities. But she failed to communicate that vision to the staff, and when they saw the first process automated by RPA, they assumed their positions would soon be made obsolete. The best talent departed, leaving the department hampered in even completing the automation and hollowed-out in terms of transitioning into strategic value-add work.13

Entry point: The right part of the organization for impact and success

The entry point for redefining work is the part of the organization where refocusing workers on collaborative problem-solving has the best chance of succeeding (in the near term and with modest resources) and where creating new value has the greatest potential for broad and meaningful impact. The choice of entry point will be guided by where the champion has control or significant influence. And the entry point needs to be a part of the organization that can free up significant capacity for workers to participate in the pilot. The goal is to identify a frontline group from which 15–60 volunteers can be solicited to participate in the proof-of-concept workgroups.14

Freed capacity means the amount of time that workers in the target group have free from day-to-day tasks to engage with a workgroup to understand and address new problems or opportunities. Fundamentally, this will be the day-to-day work of those frontline workers—it isn’t a 20 percent passion project, access to a lab, or a rotation onto an innovation team. Workers need space and time—at least 75 percent of their working hours—to successfully work differently, and they can’t do that if they are still expected to execute an overfull plate of tasks they were doing previously. In practice, this might mean redesigning some jobs and processes and consolidating tasks onto fewer workers to more fully free others for the pilot, rather than just freeing up a portion of everyone’s time.

Several organizations we studied found capacity by adopting a principle of simplify to guide decisions that would eliminate unnecessary tasks and create space for employees to embrace new work. They took a more critical look at what they do and simply decided not to do parts of it anymore. A less obvious way to create capacity is to temporarily relax a frontline operational metric and give the group permission to develop more relevant metrics and methods that better fit the desired outcome. Redesigning jobs to take advantage of emerging tech can also be an effective way to free up capacity, but if it isn’t already underway, the organization probably can’t try to kick off redefining work at the same time as it kicks off implementing emerging tech.15 This is also where communication of the vision comes into play, because in the near term, this type of arrangement may create stress and anxiety for those left behind with the tasks, as well as those who no longer have them.

The best chance of succeeding and the greatest potential for significant impact should guide further targeting of an entry point. Potential entry points can be assessed and plotted against these two key dimensions. Where could groups of frontline workers have an impact that matters to the company, and among those, which are most conducive to a pilot successfully getting off the ground, gaining momentum, and achieving the potential impact? Ideally, the entry point has a large possible impact with a high probability of success. In real life, there will be tradeoffs, but it is useful to look first at what type of impact will matter to the organization.

Smart moves generate meaningful impact. The results grab the attention of leaders and motivate others to take action because they address something that the organization needs to change to boost performance. In other words, the most meaningful results are those that address a metric that matters. As figure 4 shows, identifying the metrics that matter can be an iterative discussion as the champion, other leaders, and management align on what is most pressing for the company and what frontline workers can influence. Together, they can home in on areas of the organization that have the potential for outsized impact, on a metric that moves the needle for the company’s business performance.

The smart moves approach aims to create momentum that shifts the organization into taking action, to understand the future of work rather than just talking about it.

For example, a group of finance leaders might meet together to determine, where among all of the smaller RPA initiatives going on to reduce processing costs, exists an opportunity to move the needle on new revenue from existing customers, a pain point for the company. One department head brings up some new data analysis that suggests that retention among customers who experience a bill collection event is very low, yet more and more customers are experiencing these events. The accounts receivable department has been rapidly automating and might have the ability to deliver new types of value to the business or the customer, related to the types of payments and collections data with which they work. Identifying a starting point based on where the frontline is can drive a meaningful operating metric and helps avoid the trap of “just another” incremental change initiative.16

In addition to making an impact that gets noticed, the smart moves approach aims to get started—quickly and without huge investment—to create momentum that shifts the organization into taking action to understand the future of work rather than just talking about it. So, success for a proof-of-concept occurs at two levels; not only the actual impact but, as anyone who has tried to launch an initiative in a large organization knows, just getting the effort launched, staffed, and allowing it to run its course.

What are the characteristics of an entry point that make it more or less likely to succeed? Several factors can affect the likelihood of being able to move quickly, effectively, and to see meaningful results in a given part of the organization. The goal is to minimize or mitigate risks to the pilot without minimizing the impact.

- Business unit versus function. Business units may have more degrees of freedom and an orientation toward trying new things because they are already oriented to the market. And generally, making a direct impact on the customer—for example, a novel approach to an unmet need of an important account—gets noticed. In some sectors or companies, however, that direct line to the customer may be perceived as too risky, constraining the workgroup’s ability to address customer needs—particularly needs for which the customer hasn’t yet asked to be met. Another risk is that touching the customer may require too many formal approvals, updates, and alignment for any action the workgroup wants to take, slowing or stalling the effort. Functions that support enterprise operations often are already at the center of many performance pressure and organizational change catalysts, with automation and other future of work initiatives underway; most IT, finance, and HR organizations are well aware that everything is changing. They may be perceived as having a lower risk because their influence on the customer is often less clear and they have more difficulty showing meaningful results to the rest of the company. At the same time, because functions reach across the organization and are often mission critical, getting started in a function may attract both more risk and more potential for impact.

- Self-contained versus interdependent. Potential entry points exist along a spectrum, depending on how much their current work touches, supplies, or relies upon other organizational units or functions. A more self-contained unit—think call center—is likely to have a lower risk related to needing to align with internal customers and suppliers, or other types of organizational pressures so it may be able to redefine work more quickly. However, any learning or results may be easier to dismiss as irrelevant to other parts of the organization. Interdependent units, such as IT operations, may face greater pushback and obstacles to shifting the objective and focus of work, but the results will garner broader attention, organically, as the group interacts with others across the organization.

- Motivated frontline supervisors. While at most a handful of frontline supervisors will be involved in a proof-of-concept, those who are must be open-minded, risk-tolerant, and committed to better serving their customers, internal or external. As the frontline workgroups’ leaders and coaches, they model a growth mindset and the iterative work of seeking data and context, taking action, and reflecting and learning. They are critical to both the initiative’s near-term success and ongoing adoption and improvement of the redefined work.

- Area in which workgroups already exist. Most companies don’t have what we’ve defined as workgroups—groups of three to 15 people who spend their days working flexibly and collaboratively. But many do have groups and teams, often working independently rather than collaboratively, on the same type of activity in parallel (for example, a strategic innovation group) or each doing a sequential part of a process (for example, an accounts payable team). If a target frontline area is already accustomed to working with others, or even working specifically with each other, it isn’t a large change to form the workgroups to do the new work. The danger: They may subconsciously dismiss the degree of change implicit in redefining work in the pilot. They may not feel or appreciate that something new is being expected and therefore fall into business-as-usual behaviors and practices unsuited to undefined, collaborative work that taps into their human capabilities to find fresh ways to create value.

- Supportive leadership. The leader and managers of the entry point need not be actively involved, but they must be supportive enough to not get in the way and to make sure that middle-level managers don’t get in the way either. For example, if a CFO is championing redefining work in the finance function, but the head of payments is under pressure to clear a growing backlog without expanding headcount, the payments manager may resist freeing up resources to participate in the pilot, may assign a few poor performers, or may even pull resources back from the workgroups every time his group misses a metric. Supportive leadership can help insulate the front line from management and institutional pressures.

- Type of workers. With support, workers at all levels of the organization should be able to focus on creating value and working with others to address complex challenges and opportunities. Some types of workers, however, may require more support to be effective in this redefined work, and some may need more help or convincing to shift mindsets and be motivated and optimistic to take on the challenge of redefining work. A group of workers who have already had some exposure to the tools of improvement efforts or quality circles or who already have some latitude may be an easier place to start. The risk is that they (and the rest of the organization) don’t appreciate what is different from their prior experience, and continue to focus on process improvement or task force participation under the label of redefining work and as a result, don’t achieve significant impact.

- Edge versus core. A further consideration for some companies will be whether they try to begin redefining work on an edge or in the core. The core business involves many stakeholders, many oriented toward preserving the status quo. An edge is a new growth opportunity that exists on the periphery of the company’s current business, markets, or domains—for example, wellness relative to an insurance company’s health insurance business—but that has potential to be important to the business because it aligns with the direction of broad underlying trends.

An entry point in the core must contend with outright resistance, risk aversion, and bureaucracy, all of which argue against speed and modest investment. However, core workers also have knowledge of customers, data flows, and relationships, which may allow them to better identify and address unseen problems and opportunities that could drive bigger, more meaningful impact for the organization.

The major benefit of entering on an edge is that edges touch fewer stakeholders and aren’t integrated into the organization’s core processes, systems, or resources. This insulates them from organizational pressures, decreases the risk associated with failures, and makes an initiative less likely to get slowed down in organizational processes. Managers and frontline workers at the edges are also typically more open to change and less bureaucratic, with an orientation toward taking risks, doing things differently, and being more comfortable with the ambiguity of looking for the unseen in a broader context. The downside of starting on an edge: The rest of the organization, made aware of the results, may find them unconvincing or irrelevant to motivate broader change.

Smart moves can lead to outsized impact. Doing the heavy lifting on the front end to find the right catalyst, champion, and choose the right entry point—without getting bogged down in massive approval, alignment, or planning processes—maximizes the chances for a successful proof-of-concept for redefining work toward value creation. To start creating that value, the organization has to create the right conditions for redefined work and provide ongoing supports to achieve impact.

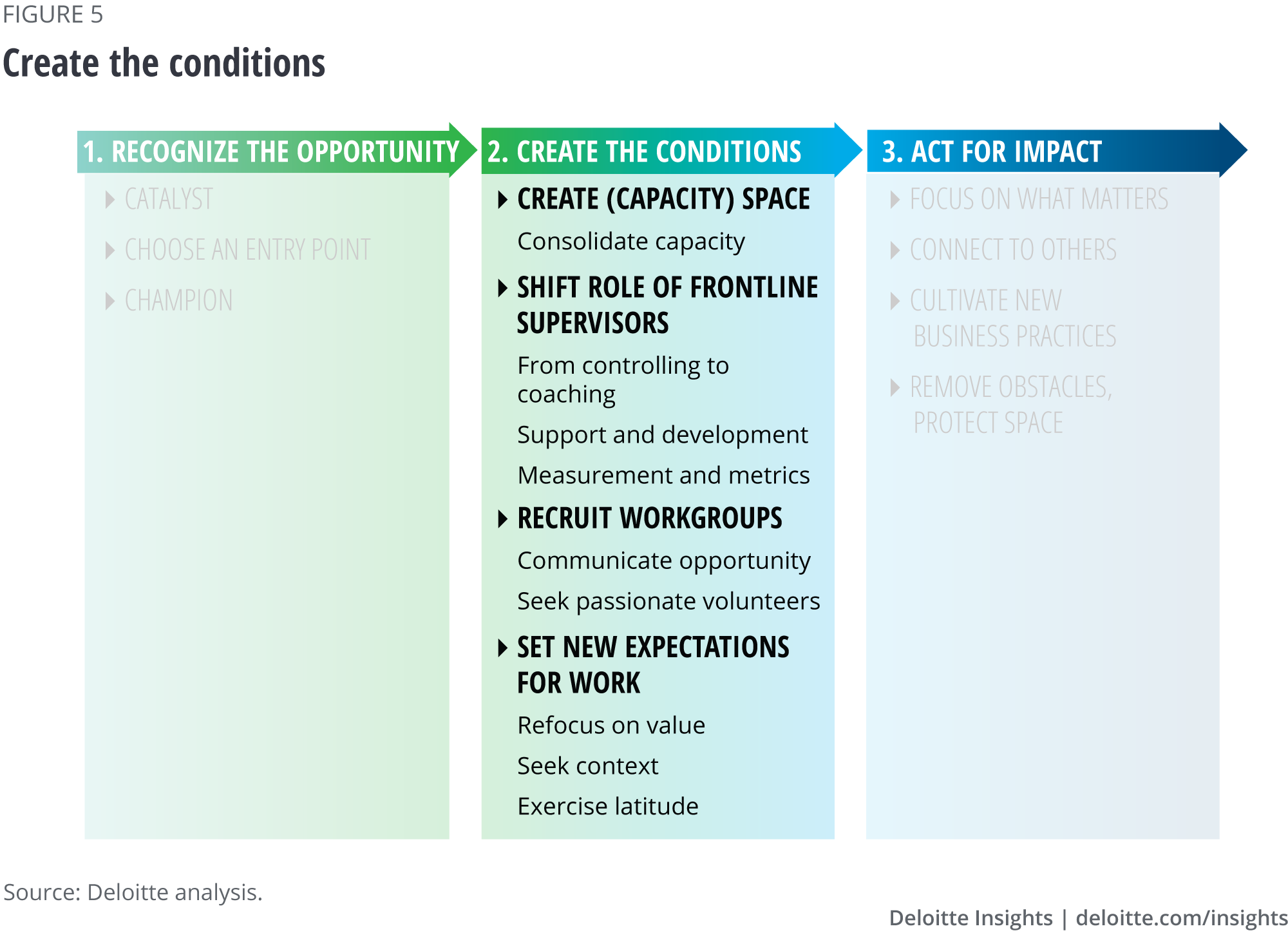

Create the conditions: How will you redefine the work?

Redefining work constitutes a dramatic change in most organizations: in leadership style, mindset, organizational structure, roles, everything. But trying to change everything at once is unlikely to succeed. Getting started quickly and generating significant results as fast as possible creates a tension: Move fast with too little thought or planning, and the effort will achieve little or no impact; spend too much time trying to get systems and leaders aligned to support redefining work, and the effort may stall. The idea is not to ignore planning and alignment entirely but, rather, to be thoughtful about designing the pilot, selective about planning, aligning only what is most critical, and mitigating other risks and contradictions—while doing all of this at the most local, experimental, lightweight level possible. For example, comprehensive contingency planning misses the point and wastes time. So, too, does trying to fix compensation or performance management systems that are out of line with this type of work; although these management systems will eventually have to be addressed, in the near term the overriding goal is to create compelling proof for moving in a new direction.

We’ve already discussed what smart looks like in terms of catalyst, champion, and entry point; the next question is, “What is required to make a successful start for the pilot group?” A few moves can create the right conditions for frontline employees to take on redefined work: create capacity, recruit workgroups, shift the role of supervisor/managers, and shift expectations about work. Taken together, these moves prepare the frontline to do different work by addressing constraints, expectations, collaboration, and motivation.

Shift the role of frontline managers/supervisors

Implicit in redefining work is shifting from command-and-control to giving frontline workers visibility of the broader scope of what matters to the organization and the customer, and more latitude to address it. A key condition for redefining work, then, is to change the role of the frontline supervisors who will be involved in the pilot, from managing and controlling workers to coaching, guiding, and connecting workgroups. Closely overseeing tasks and dictating outputs, while helpful for efficiently delivering a product at scale, are hardly conducive to empowering employees to use their diverse talents, expertise, and capabilities to identify new opportunities and create new value.

Frontline managers that are already passionate about making work better and serving the customer more effectively will be the strongest advocates for a successful pilot. We’ve seen examples from across industries that the quality of managers really matters in balancing latitude with impactful direction—and in keeping workgroups connected to a larger outcome, while also staying accountable to getting better and better. For example, at the building site of a 43-story tower/historic building renovation, Webcor, a West Coast-based general contractor, experiments with different formats of meeting with subcontractors’ foremen and supervisors to drive awareness and accountability of higher-level goals—and to unite around safety given the many and expanding risks associated with a large, complex building project. As one project supervisor pointed out, with the project moving into a new stage, the number of subcontractors and workers on site was about to double, some of them new to construction. Webcor couldn't achieve its safety goals for the project without engaging the subcontractors’ frontline supervisors to prioritize safety and empower their workers to identify and resolve safety issues.17

This shift for frontline supervisors has to be explicit. They are being asked to behave in a new way, to stop doing what has been successful for them until now, to extend some trust rather than ensure compliance, and to trust that the organization won’t penalize them if output falls short of expectations. This shift involves several parts:

- Expectations/vision. The supervisors need to know what the vision is—what are the key differences between work today and redefined work, and what is the proof-of-concept’s intent and rationale? Part of this is also communicating the growth opportunity for the managers who participate.

- Performance. For many managers, performance metrics will be top of mind. If they are being asked to stop managing a group of workers, the handful of supervisors on the pilot may need their normal metrics to be relaxed and have some immediate and near-term incentives—for themselves and to offer the groups they lead—to encourage letting go of what they know and take risks.

- Development. Managers need practical help to switch to a coaching role. While most training of frontline supervisors in their new role will come from just doing it, most will benefit from some formal training and ongoing support to understand what new behaviors, approaches, and tools might be effective in their role as coach and guide. Initially, supervisors will help frontline workers understand the new expectations and help the workgroups focus on what will have an impact, break down complex challenges into manageable parts, reflect on what they’ve done and what they’ve learned, and navigate group dynamics. The frontline supervisors can help identify and connect the workgroup to resources that might be relevant, such as a data feed from another part of the business, and also to locate where the workgroup needs additional support—for example, instruction in a type of analysis or a tool to share files or group intervention. Supervisors will also coach individuals in the group, providing feedback and support to help them tap into their core human capabilities and become more effective in the group environment generally or in specific types of activities. Coaches should look to eliminate or mitigate obstacles to the work or the use of capabilities.18

- Focus. Supervisors need to know specifically what to focus the workgroups on, at least to start with, in the pilot. This should flow from the metrics that matter analysis that the champion and higher-level managers did to identify what entry point could have the most impact. In some cases, the leaders might want the workgroups to begin by focusing on specific known problems or by addressing automation opportunities, to get comfortable with more creative, collaborative, undefined work.

- Support. Managers need ongoing support to get better at coaching the workgroups and individuals and to improve their understanding of what matters to the organization and how to connect that to what the workgroups are doing.

For frontline supervisors, empowering their subordinates, encouraging them to take risks, and supporting them through failures is a mindset shift as much as a behavioral one. They need to adopt a growth mindset for themselves and others to believe change and improvement are possible. The transition might be difficult in a group in which the dynamic has been more about policing infractions—yet even there, examples from NUMMI, Quest, and elsewhere show that it is possible to make the transition.

For middle-level managers and leaders who sit above these pilot workgroups, the most important thing is to get out of the way of the frontline workgroups. Ideally, they understand the opportunity to redefine work and what types of changes are required to do the proof-of-concept, and can be supportive. But what is required—and this expectation should be communicated from the champion—is that they release some control and don’t try to redirect the workgroups back into the typical day-to-day work. If frontline supervisors and managers see the champion and leader model this behavior, in attitude and actions, they will likely be more able to make the shift themselves and help their teams shift more quickly to new ways of working.19

Recruit workgroups

People cannot do this type of work in isolation: Groups are essential to accelerate learning and impact, increase motivation, develop capabilities, and support skill and knowledge acquisition. As figure 6 illustrates, three types of groups facilitate and support redefined work, not just for getting started but for getting better and better at creating new value across the organization. Though we focus on the workgroup as a key component for starting to do redefined work, cells, and communities of practice are critical for sustaining and scaling redefined work in a way that continuously amplifies and increases organizational impact.

Workgroups are where redefined work gets done, where workers come together to get better at seeing and addressing complex problems and opportunities. Research has shown20 that workgroups can be the platform for accelerating organizational performance through ongoing cultivation of new business practices that tap into and develop core human capabilities.21 With companies facing ever more complex challenges, the opportunities to create new value will tend to require greater understanding of context, varied experience, specific skills, and fluency in technologies that no single individual is likely to possess. Workgroups allow frontline workers to better see and address unseen problems and opportunities, leveraging each other’s strengths, generating new approaches, and drawing more nuanced understanding through productive friction. The workgroup is also a platform for developing individuals. They learn from and with each other, sharing explicit and tacit knowledge, creating new knowledge, and developing competence and confidence in using their human capabilities as they work together on challenging problems.22

Remember, start small but smart: One workgroup won’t be a meaningful proof point, while 10 is a daunting number to effectively coach and support. Three to six workgroups is a good initial target to make a noticeable impact without being cumbersome or chaotic.

How to form workgroups? Seek volunteers. As with the supervisors, it is easier to run a pilot with people who believe the status quo isn’t working and want to help create a new system. That doesn’t necessarily mean that you’re looking for top performers, given that you’re asking people to do something different from tasks they feel comfortable and competent doing. People who are disgruntled or who don’t always hew to rules and policy can be passionate about changing the way work is done and excited about the opportunity to create more value.23 The trick is communicating—both the chance to participate in the pilot and the greater opportunity to take on the big challenges that will move the organization into the future. This must be done in a way that taps into frontline workers’ curiosity and desire to take on challenging, meaningful work and overrides the insecurity or cynicism that new change initiatives often trigger. The frontline workers and supervisors who opt in will tend to have a growth mindset and be primed for the ambiguity and discomfort that come with making the shift from defined tasks to undefined problem-solving.

Seek volunteers. It is easier to run a pilot with people who believe the status quo isn’t working and want to help create a new system.

Leaders should solicit volunteers, individual frontline workers as well as entire workgroups if they exist, from the entry point. Because the pilot is necessarily kept small, avoid anything that could be interpreted as penalizing those selected to participate or those who aren’t—the desire from the frontline may be surprising. At one company, for example, teams that wanted to participate in a pilot improvement program were asked to put together five-minute presentations about why it mattered to them to compete for one of the coveted slots. This type of competition allowed frontline supervisors to show their creativity, enthusiasm, and passion, and to be specific about their reasons.

Similarly, ATB Financial had an application process to solicit passionate individuals to be part of the company’s G Evangelist program to help coworkers understand and then redefine their work around the new technology implementation. Leaders were shocked to receive more than 300 applications for the 50 pilot slots during the first week of the application process.24 Another approach is to ask individuals or workgroups to be specific about what problem or opportunity they’d like to address and why. In the mid-1980s, when aluminum maker Alcoa redefined the objective of work to be “perfect safety,” leaders looked for the frontline workers who had filed the most safety complaints with the union and made them the first to have their work redefined to focus on understanding and addressing safety issues.25

Whether drawing from individuals or preexisting workgroups or teams, it is important to try to attract as many diverse perspectives as possible and to form groups that will maximize productive friction. Groups formed around “fit” can end up with similar perspectives that won’t generate new and better insights and approaches.26 Note that workgroups aren’t just about the people: Technology—machines, robots, analytics—can be vital parts of the workgroup.

For entry points where teams already exist, leaders have to decide whether to repurpose the current teams or create brand new workgroups. Creating new workgroups offers a clean slate for people to work differently. Workers may be more able to shift their mindset about what work is because they have also changed who they work with and possibly their surroundings. However, it takes time to understand each other’s styles, strengths, and capabilities. Without trust built over time, members of a new workgroup might be more hesitant to speak up or take risks. If current teams work well together and are diverse, it may be most efficient and productive to repurpose them into workgroups.

Set new expectations about work

It’s critical to explicitly reset frontline participants’ understanding of what their work is and what is expected of them in the pilot. It is worth investing a few days to have the new workgroups engage with what the new expectations mean in a supported environment. This is the actual “redefining”: Their objective is to focus on new value creation rather than task execution. They will do this by working collaboratively in workgroups on challenging issues that don’t have predefined outputs or prescribed approaches. In the pilot, they will be expected to seek context to more deeply understand customer needs, and to exercise latitude to help the workgroup better understand the problem and possible solutions. This represents a big change, so it’s also useful to be explicit about how leaders will support participants in the pilot: in the form of coaching, additional resources, and guidance on tools—and through the social, “learning through doing” workgroup structure itself.

Even those comfortable with handling exceptions and fire drills prefer to know what is expected and how to do it. People also take pride in having identities wrapped up in being known as “the person who knows how to do X task” or “manages Y process.” If leaders are asking participants to let go of those identities, people would appreciate acknowledgment of their current value. For example, in one finance department, the financial planning and analysis (FP&A) work was understood to be pulling and assembling data for leaders. Specifically, the team was tasked with pulling more than 60 reports from several different source systems for a monthly finance leadership meeting; the workers’ expectations of work were oriented around producing that predetermined output. But when they asked what purpose the reports served, they realized that not only were there better ways to achieve the same outcome—there was potential to deliver a far more valuable outcome. By asking which insights were useful to leaders and what other types of insights would be helpful, the FP&A team consolidated the necessary financial data into a dashboard that the leadership team could both quickly glance at and drill into. By creating a new expectation for what their work should be (value-based rather than output-based), the team was able to rethink the work they were doing and expand the outcomes, and value, for their customer, the finance leadership team.

Redefined work moves from a world of defined tasks to address known needs to one of undefined activities used to address unknown problems and opportunities. Inevitably, this leap in ambiguity can make many workers and managers uncomfortable. Guardrails—about what customers or systems they can or cannot touch, for instance—can delineate the extent of their latitude and serve as anchor points to help workers navigate more confidently and can be adjusted over time.

Initially, workers may need to be given a problem to start with, something known and possibly more structured, to gain confidence with redefined work. The champion and leadership will probably surface several partially defined problems in the process of identifying a good entry point. Even here, though, it should be framed as a real need, a challenge facing the organization; the workgroup will do the work to understand the problem and develop, test, and refine approaches to solve it. Over time, leaders will look to the workgroups to move beyond the initial definition, to identify additional problems and opportunities based on commitment to a shared outcome.27

Inevitably, the ambiguity inherent in redefining work—moving from a world of defined tasks to address known needs to one of undefined activities used to address unknown problems and opportunities—can make many workers and managers uncomfortable.

During the pilot, the formal incentives for frontline workers may not fully align—and may in some cases conflict—with the new objective. Leaders need to recognize and acknowledge this misalignment and try to take at least temporary measures to alleviate the burden (psychological, emotional, financial) of conflicting incentives that can lead to cynicism, lack of commitment, and underwhelming results. Individuals may be more influenced by the immediate, both in terms of near- to real-time rewards and recognition and in terms of commitment to the workgroup and team members with whom they interact daily, at least for a while, so changing compensation and performance management systems shouldn’t be seen as a prerequisite to getting started. If people have been measured or rewarded on specific metrics, they need to be reassured about how their performance will be assessed in the pilot—and that they will not be penalized for good-faith participation.

Expectation-setting will look different for every organization, depending on the culture, the type of workers chosen for the pilot group, and how different redefined work is from the work those employees are doing today. Understanding the gap between what workers currently do and what they’re being asked to start doing will guide how intensive expectation-setting should be. Some groups, such as the FP&A team, may only need to ask better questions about why they do certain tasks. Other groups may need illustrative examples of what redefined work looks like in order to adopt this new way of working.

Once workgroups have been formed, workers know what success looks like, and supervisors are prepared to provide guidance, the work of actually doing redefined work begins. Maximizing the pilot’s chances for success and impact will require various forms of ongoing support.

Act for impact

Any large change initiative comes with a laundry list of activities and supports. But which moves matter? What supports really make a difference for redefining work, and how can they be implemented rapidly to a degree appropriate for a pilot?

Redefining work for an entire organization ultimately implies changing everything: leader practices, business practices, and the work environment, including the management systems and even infrastructure we take for granted today. It’s hard to imagine any large organization having the appetite to take on all of that—or doing it fast enough to address current pressures. That is the rationale behind starting small in this approach: First, build motivation, conviction, and commitment. Then change the whole company.

Based on the experiences of organizations that have tried to fundamentally change frontline work or become value- or customer-focused, we have identified a few ways to actively support frontline employees on the road to unleashing their potential. Granted, in trying to simplify we risk missing some details that make the magic,28 but these moves seem to matter: helping the frontline know where to focus, connecting individuals to each other for social learning; connecting workgroups to customers and other resources to expand their understanding and vision; cultivating new work practices that accelerate performance through continuous learning through action; and leader practices that focus on providing air cover, demonstrating discipline, and removing obstacles, whether in the physical, virtual, technological, or organizational environment. These moves each have a dimension of leader practices, business practices, and work environment considerations.

These supporting moves are not mutually exclusive—for example, posting a shared outcome on the wall of a team room may be a work environment move that reinforces the business practice of committing to a shared outcome; a technology platform may enable frontline supervisors to connect with one another more easily to get support and share coaching techniques. But it might also help them to connect their workgroup members to others to gain insight and expertise that might accelerate impact. Taken together, the moves form an active, evolving support structure for the pilot workgroups to enable the organization to start learning how to redefine work, without waiting for a large transformation of systems or processes.

Underlying these minimal supports is the need to maintain and tap into worker motivation. Without motivation, workers will naturally avoid the discomfort of cultivating new work practices, taking actions that carry the risk of failure, and exposing their vulnerability and lack of knowledge. Motivation can support the individual through gaining new knowledge and skills and struggling to achieve results. While the desire for status or financial incentives can provide some extrinsic drive, the most effective and sustainable form of motivation is intrinsic and taps into what we call worker passion. This type of passion is characterized by a questing disposition that actively seeks out new challenges, a connecting disposition that seeks to build trust-based relationships to help address challenges, and a commitment to making a significant impact in a domain. The need to eliminate or mitigate management practices and environmental elements that discourage passionate behavior can guide how leaders support redefining work. In addition, leaders can encourage passion through practices that demonstrate commitment to preserving and harvesting the frontline’s insights and innovation—for example, by closing the loop on all solutions brought forward by the workgroups. Worker passion can counter the types of defensive reactions that tend to undermine a company’s ability to respond effectively to mounting performance pressures. At the same time, even the passionate need guidance and models of how to unleash that passion in a constructive way so that others can build on it and the group’s learning and performance can advance.29

Focus on what matters

Even without focus, empowering the frontline can result in many, many incremental improvements. This can create a great problem-solving culture that in more predictable times would be sufficient for staying ahead of the competition. However, with more rapidly changing and unpredictable requirements, this type of incrementalism can still miss the most significant opportunities for new value.

A key aspect of the coaching and guidance that the frontline supervisors will provide for the workgroups is to help them understand what types of impact, and what types of problems, will be most significant to the organization. This is initially dictated in part by the catalyst and metrics that matter discussions that helped identify an entry point in the first place. The leaders used a key operating metric or pain point to identify a few frontline metrics that the workgroups have control over. These frontline metrics are leading indicators that can be tracked day to day, week to week to help the pilot workgroups understand what type of impact they are having.

Over time, as the workgroup moves beyond taking cues from problems the supervisor or other leaders have identified and begin identifying other opportunities, they may begin seeing opportunities everywhere. This is a good problem to have! But no one has enough time or resources to pursue everything, and at that point, a workgroup will need guidance to evaluate what problems and opportunities are most worthwhile and have the greatest potential for significant new value creation.

Connect to others

In a world where engaging in the right knowledge flows can be more important than protecting knowledge stocks, workgroups and individual members should be encouraged—and expected—to connect with others. Connecting people and workgroups to each other, to other resources, and to customers helps to create context and drive learning that accelerates both group performance and individual development.

Leaders and frontline supervisors can help workgroups be aware of the importance of different types of connections—and in some cases can help facilitate them. For example, most people know that strong, trust-based relationships are important, but if the objective is to create new value by identifying and addressing what has not yet been seen, workgroups may benefit from exploiting individual members’ weaker connections. These connections provide an additional source of diversity and may provide a fresh perspective, needed expertise, or a different audience to test an approach. That said, workgroups may not recognize their many relationships as a valuable resource on their own. Leaders can highlight and encourage connections through a variety of physical, technological, and organizational supports tailored to specific needs—for example, colocating a virtual workgroup for part of the time, locating the group in a space closer to the customer, implementing a platform to help individuals access relevant information to connect with others, or hosting weekly lunches. Frontline supervisors can model the behavior, and benefit from it, by connecting with each other and with leaders and exploring and deepening other types of connections to internal and external communities.

Certain types of connections should be explicitly forged: For example, leaders can assign individuals to cells (see figure 6)—five to 15 people drawn from across workgroups—to build deeper relationships that will encourage and sustain them as they get into the hard work of developing new capabilities, skills, practices, mindsets, and learning to get better at the work of problem-solving. Cell members support each other’s individual growth and cultivate a feeling of membership, belonging, and accountability, which, because it is a small set of known people, is incredibly motivating. Unlike workgroups, the goal isn’t friction so much as providing a space to be authentic—to reflect with others, process their work, and gain new insights. There are many examples of cells in the wild, including pro surfers, CEO support groups, and microfinance groups.

Another important type of connection for workgroup members will be to form communities of practice, which often develop organically. In these communities, individuals can connect, seek expertise and knowledge, share experiences, and acquire new techniques, approaches and tools—specific to a domain or specialty—from others, outside the workgroup. To use an old example, think of the Xerox service technicians who worked independently but would meet every morning to trade stories and would sometimes accompany each other to consult on particularly challenging problems; their goal was to accelerate tacit learning and build new knowledge.30 Similarly, hospital rounds where residents “ride-along” together to encounter specific stories and challenging problems is a form of social, situated learning. Observing peers and those with greater expertise applying different tools and techniques in the moment can lead to a broader understanding and deeper technical fluency. The more people connect, the more likely they are to be equipped with the right information and resources to recognize a previously invisible opportunity and tackle it. A related concept, the network of practice, is typically much larger and more formal. A network can help an individual stay current with changes in their domain, acquire new skills, or understand new requirements, technologies, technical advances, or regulatory changes, often through more traditional means.31 In the near term of the pilot, however, these communities and networks of practice will be less important.

The other way to help workers is to connect them beyond the organization, to the outside world, and help them see and understand the needs, aspirations, and constraints of others—customers, partners, and other participants. This is an area in which technology is starting to play a bigger role—for example, in bringing customer data, behavior, and preferences into the production line or the billing process. And it’s not only customer survey or satisfaction metrics but, rather, a real sense of who the customer is and where they have unmet needs. Consider how some companies are rethinking what used to be a mundane task—sending out notices on delinquent accounts—by forming diverse collections groups that include people from marketing and product and sales, as well as collections and analytics specialists. These groups are doing analytics and customer segmentation to create a profile and better understand who that customer is, their value to the company (perhaps late payers are more likely to buy a full bundle), and creating customized letters that better resonate with the customer to cultivate loyalty as well as encourage payment. This is new value to the customer and the company, and it greatly expands the understanding of each of the people pulled onto these groups. It’s important to connect to the outside because the problems and opportunities of customers are endlessly variable and so are the ecosystems, technology, and resources available to address them.

Beyond connecting the workgroups, individuals may need coaching, either from the supervisor or a third party, on how to develop and use trust-based relationships if they have been in a culture of transactional relationships. In this, leaders also become brokers—those who facilitate the social processes of connecting and assembling people, knowledge, and resources from multiple domains both inside and outside organizations.32

Cultivate new business practices

New work focused on creating new value rather than executing standardized tasks requires a new way of working. As we discussed earlier, workgroups will ultimately be engaging in activities to identify unseen problems and opportunities, to develop new approaches, to test and tinker with those approaches, and to iterate and learn how to create more customer value.

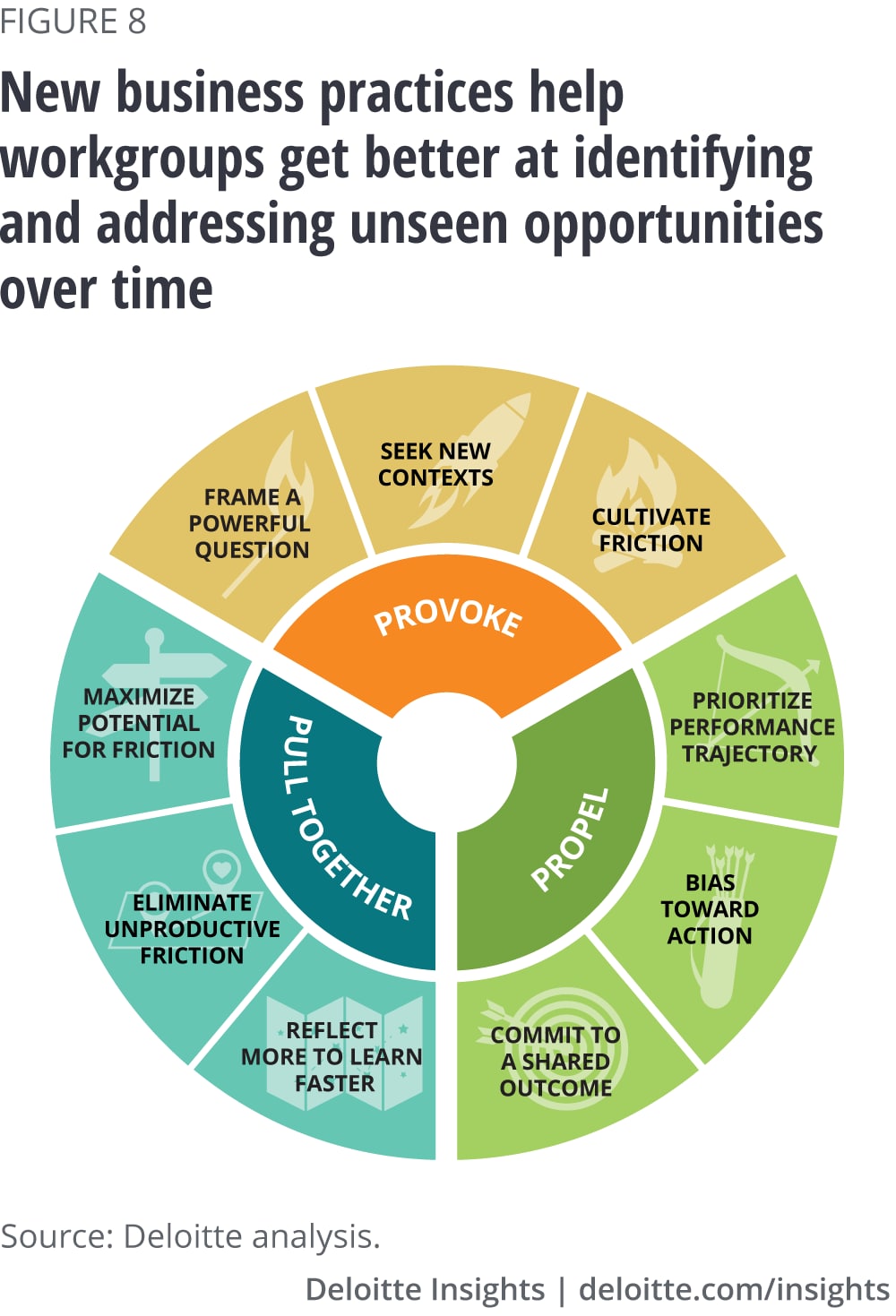

In addition to drawing from a wealth of tools and techniques developed over past decades of continuous improvement, including agile, and other methodologies, certain practices unique to workgroups can help them get better at the actual work of collaborative problem-solving. A practice is the way work actually gets done, the activity involved in accomplishing a particular job;33 we use the term in contrast to a formalized process, referring to the way work and information flow is organized and coordinated across stages. Process is how work can be done in a controlled and predictable environment where the solution is understood and predetermined. Our prior research in business practices uncovered nine practices that can accelerate performance in workgroups (see figure 8). These practices can help provoke the workgroup to think differently, propel a group into action, or help members pull together to harness diversity.

No workgroup can tackle all nine at once. Initially, there are three that will help them get started by reinforcing the changes needed to redefine work:

- Commit to a shared outcome.34 A meaningful and significant shared outcome helps to focus and align workgroup members and drives them to constantly take action to achieve that outcome. Research indicates that groups with shared outcomes are only half as likely to feel that competing priorities hold back the group and a third as likely to complain about constraints due to corporate politics.35

- Frame a powerful question.36 A powerful question, possibly posed by the champion or another leader, can serve as a statement of purpose that helps lift the workgroup out of incremental thinking and challenges participants to answer it. The right question transcends current assumptions; it can grab attention, capture interest, and provide inspiration to help lift the workgroup out of the day-to-day to zoom out to a bigger picture, future view.

- Reflect more to learn faster.37 Reflection is critical for learning. Action without pausing to consider what was done, what the impact was, and what has been learned is a waste of time. For workgroups, reflection and adaptation—before action, during action, after action, and outside action—can be very powerful for achieving greater impact.

Ultimately, workgroups will want to adopt all nine practices to accelerate performance improvement. The practices are mutually reinforcing and counterbalance one another. To effectively use the practices, workgroups need to evolve them in their daily work—the nature of a practice is that it will evolve differently wherever it is used, so each workgroup should be encouraged to develop its own versions. Over time, workgroups will cultivate additional practices, prioritizing different ones based on their needs and unique challenges.

Remove obstacles

It is important for leaders to identify and remove the obstacles—both immediate and long term—that the frontline workgroups face in doing redefined work. Obstacles could be political, cultural, systemic, management, or work environment-based—anything that prevents participants from being fully effective at redefined work. For large, systemic obstacles, the champion, as well as the frontline managers, should seek ways to temporarily mediate obstacles or provide cover for workers to generate a proof-of-concept for redefined work. For example, if an organization’s silos prevent workers from seeing unseen opportunities, a leader needs to be able to grant workers access to all data in their department or business unit so they can begin to see the unseen. Long term, the leader can work to provide full access to data across the organization while encouraging a more transparent culture. If a workgroup is struggling to be imaginative and creative because their work space’s rules prevent them from moving furniture or having easy access to whiteboards and storage, the leader should be able to bend those rules. Other types of obstacles might be policies that discourage reaching beyond the company boundaries for information or additional resources, a culture of blame-and-shame for failures, or a tendency to not share credit. All of these can get in the way of imagination, risk-taking, trust, collaborating, and creating.

Work environment

Our research in work environment redesign suggests that a well-designed work environment can have a critical impact on employee productivity, passion, and innovation.38 This includes the physical, virtual, and technological environment. When getting started, the minimum work environment support needed is a physical space to collaborate, virtual cocreation tools, and the right technology to build connections and see previously unseen opportunities and problems. Over time, this can be deepened to include transparent access to data, more advanced technologies that enable seamless collaboration with virtual team members, flexible spaces for collaboration and individual work, and more. These elements will allow workers to engage in redefined work in a sustainable way that accelerates performance improvement.

The role of technology

Technological advancements mean that tech is able to play many more roles in today’s workgroup than in the team of the past, where it was often relegated to videoconferencing and email. Some ways in which technology can influence workgroups of the future:

- Tech as an enabler to see the unseen. Technology can help workers see unseen opportunities by providing insights from data, giving greater access to customers, and making new products and services possible. For example, an AI bot can analyze market data, build a trends dashboard, and flag insights for the workgroup to discuss. It can also pull other relevant research materials related to the trends it flags for the group to more easily do a deep dive on the topic.

- Tech as a connector and facilitator of learning. Technology can connect workers, workgroups, organizations, and ecosystems in previously unimaginable ways. This connection facilitates real-time learning in the workflow that can be easily accessed and shared across a platform. For example, organizational network analysis and nudging technologies exist that can help workers more intentionally discover opportunities for connection by identifying coworkers who are having similar discussions or facing similar challenges. It can also act as a learning repository by suggesting who in the organization or ecosystem may be able to help with specific challenges, effectively connecting workgroups with additional communities of practice.

- Tech to cultivate human capabilities. Technology is rapidly advancing to assist humans in unlocking their potential for creativity, imagination, empathy—by making customer needs more visible and facilitating reflection, to name a few. For example, Mursion is a VR simulator on which workers can practice emotionally challenging situations, get feedback, and learn how to better react in similar situations on the job. Over time, this type of technology may help workers build empathy even with the most challenging people they deal with at work.

- Tech to increase productivity. Technologies can transform work processes, allowing humans to rapidly prototype and gather feedback in ways that are more cost-effective and present lower barriers to iteratively testing approaches.