What is work? has been saved

What is work? Deloitte Review, issue 24

10 minute read

28 January 2019

In the age of artificial intelligence, the answer to a more optimistic future may lie in redefining work itself.

Work, as an idea, is both familiar and frustratingly abstract. We go to work, we finish our work, we work at something. It’s a place, an entity, tasks to be done or output to achieve. It’s how we spend our time and expend our mental and physical resources. It’s something to pay the bills, or something that defines us. But what, really is work? And from a company’s perspective, what is the work that needs to be done? In an age of artificial intelligence, that’s not merely a philosophical question. If we can creatively answer it, we have the potential to create incredible value. And, paradoxically, these gains could come from people, not from new technology.

Learn More

View the Future of Work collection

Subscribe to receive related content

This article is featured in Deloitte Review, issue 24

Create a custom PDF or download the issue

Since the dawn of the industrial age, work has become ever more transactional and predictable; the execution of routine, tightly defined tasks. In virtually every large public and private sector organization, that approach holds: thousands of people, each specializing in certain tasks, limited in scope, increasingly standardized and specified, which ultimately contribute to the creation and delivery of predictable products and services to customers and other stakeholders. The problem? Technology can increasingly do that work. Actually, technology should do that work: Machines are more accurate, they don’t get tired or bored, they don’t break for sleep or weekends. If it’s a choice between human or machines to do the kind of work that requires compliance and consistency, machines should win every time.

But what if work itself was redefined? What if we shifted all workers’ day-to-day time, effort, and attention away from standardized, transactional, tick-the-box tasks to instead focus on higher-value activities, the kind machines can’t readily replicate? And to let them do it in a way that engages their human capabilities to create more and more value? More to the point, why aren’t many companies recognizing the opportunity to engage employees in work that creates more value, individually and operationally, and may be future-proof? The reality is that our long-held views of what constitutes work are reinforced and amplified by institutional structures far beyond the individual. Fundamentally changing the work people do is tremendously challenging.

The work-industrial complex

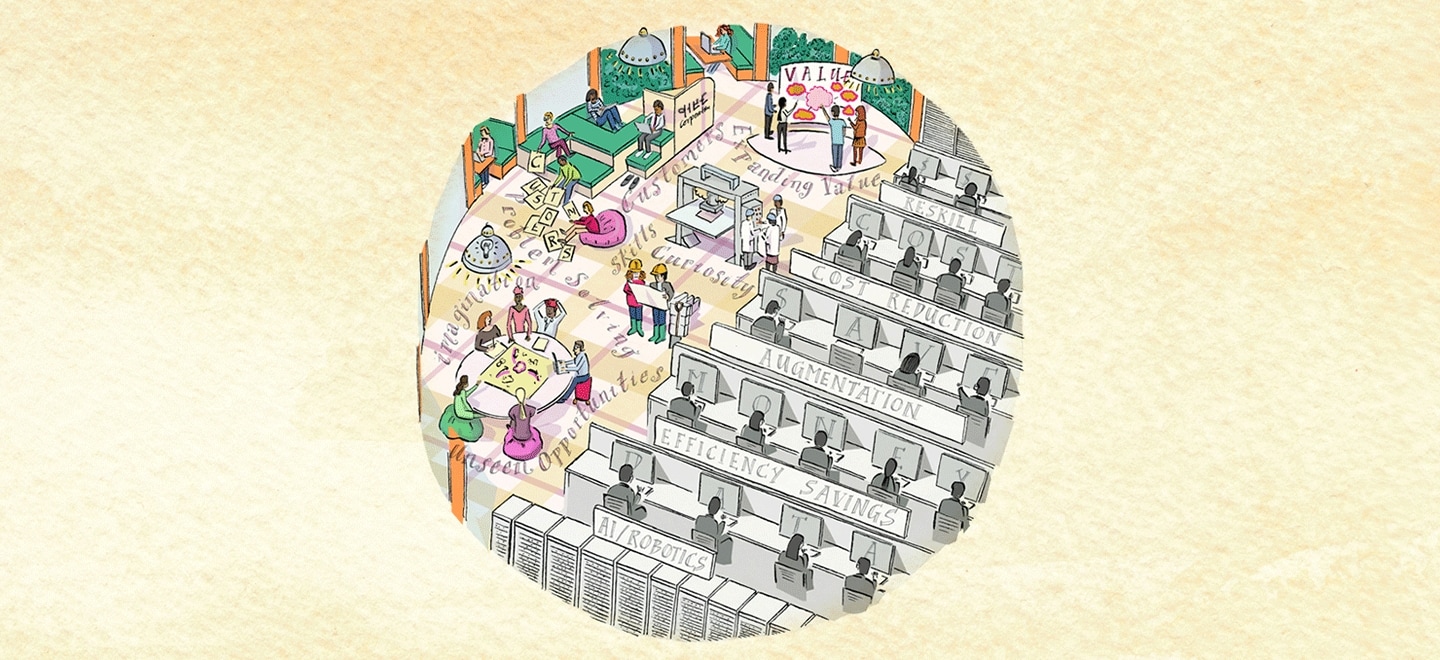

One way to measure the output of work is by the amount of value created. The problem? Many companies are stuck on a path that makes that value hard to see. Despite being lined with colorful billboards advertising “growth” and “innovation,” or declaring they’re “customer-centric” or that they value the “employee experience,” the traditional value creation path aims inexorably toward cost-cutting and efficiency, marked along the way by quarterly signposts. And there’s constant pressure to move along that path faster, since the road is getting crowded.

Most companies do this, which is understandable given the pressures they’re under. But it’s not enough. If you focus on efficiency, each successive round of gains becomes harder to eke out. Even with technology—especially with technology—it’s a game of diminishing returns, and competitors are chasing the same efficiencies, often using the same technologies. Second, while companies need to keep costs under control and find ways to increase speed and reduce waste, the way we’ve been chasing efficiency is less and less effective. Focusing on costs, particularly through headcount, and the speed of standardized and tightly defined processes actually makes people less efficient because these routine tasks and processes are ever less relevant for helping people deal with the growing number of “exceptions”—unexpected needs and events that fall outside of existing processes and standard offerings. Finally, focusing on costs reduces the ability to address new opportunities and risks missing the biggest, and rapidly expanding, opportunity to create more value.

In addition, conversations around the future of work often only intensify pressure to stick to the old path of chasing efficiency and cost reduction. A typical conversation centers on a handful of options for companies: using AI and robotics to automate routine tasks and eliminate as many workers as possible; reskilling the workforce so employees can efficiently do other routine tasks that haven’t yet been automated; or augmenting the workers so they can perform more of their routine tasks faster and more accurately. A fourth common conversation considers who will do the work and where, but the discussion is often couched in terms of shifting the same routine tasks to others so labor costs can be reduced. It seems while executives and thought leaders are engaged in a rich conversation about the future of work,1 few are asking the most basic, fundamental question about what work should be.

Job of the future: Digital twin engineer

Faster computing power, a proliferation of sensors, and exponential growth in the ability to connect with data across the organization and beyond are fueling the rise of digital twins—virtual representations of products created with 3D design software. Digital twin engineers create these virtual representations to test how Internet of Things-connected products operate and interact within their environment throughout their life cycle. Ranging from jet engines to shop floors or even entire factories, they make it possible to virtually see inside any physical asset that could be located anywhere, helping to optimize design, monitor performance, and predict maintenance. On any given day, the digital twin engineer is responsible for creating and testing digital twins, collecting information with the help of machine learning on how products are responding. This information can then be used to design new products and business models, making the digital twin engineer a critical bridge between an organization’s product and its sales and marketing teams.

For more, read the article by Paul Wellener, Ben Dollar, and Heather Ashton Manolian, The future of work in manufacturing, on www.deloitte.com/insights.

Redefining work around human capabilities

It doesn’t have to be this way. The essence of redefining work is shifting all workers’ time, effort, and attention from executing routine, tightly defined tasks to identifying and addressing unseen problems and opportunities. While automation can be a key to freeing up the capacity of the workers to do this type of work, it’s not about simply automating workers away or augmenting with technology. It’s not about changing the composition of the workforce, or reskilling or leveling up people to work elsewhere. It’s not about adding employee suggestion boxes, 20 percent time, or innovation/entrepreneur centers to the work. Redefining work means identifying and addressing unseen problems and opportunities in the work, for everyone at all levels, at all times, including and especially at the frontline.

For three decades, the Toyota Production System has not only demonstrated how much value-creating potential resides in frontline workers, but how the “unseen” is a key aspect of redefining work. Focusing on the unseen means imagining solutions that don’t yet exist for needs that haven’t yet emerged. Solving “nonroutine” problems, and seeking fresh opportunities, should be a large and expanding portion of a workload, not a small piece of a larger traditional work pie. Assuming needs and aspirations are indeed limitless, every employee could be working to create more and more meaning and value. If you get this right and find ways to unleash more value creation, you might benefit from hiring more workers rather than looking to replace people with bots.

Now, you may be thinking: What’s different about this? Our employees already identify problems and develop new products. We do rapid prototyping. We do continuous improvement. Of course, many workers today engage in some of these activities. But their primary work—what they spend most of their time doing—likely remains routine, predictable tasks. There are many examples of companies trying to give employees space for unstructured, creative work through initiatives designed to fuel passion, spur innovation, or improve engagement. But the benefits are limited because the new work is added to the daily to-do list and often gets squeezed out by the more time-sensitive routine tasks, rather than a fundamental redefinition of the work itself.

A way for workers to effectively identify and address unseen problems and opportunities is to cultivate and use their human capabilities to do the identifying, solving, implementing, and iterating activities (see figure 1). For instance, they may employ empathy in understanding the context in which a customer uses a product and encounters problems. They may use curiosity and creativity in choosing and using tools to explore root causes and gather and analyze information. They may use imagination in drawing analogies from other domains, intuiting interactions and relationships, and seeing potential solutions that had remained obscured. They may improvise around a process, tweaking their behavior and interactions with tools to see if they can do it faster or with better results for the current conditions. Being able to address problems and opportunities in a flexible way is key. Without bringing these human capabilities to bear on the work of problem-solving and solution development, the work may change but companies won’t realize the potential of this opportunity to refocus their most valuable resources.

Another key attribute of this vision of work: It will continually evolve. Problem identification and solution approaches are often used with the intent to fix a process, correct a deviation, or remove an inefficiency, with the goal of feeding back into more structured, tightly defined work, where loosening the structure is only a temporary means to move the process forward. But the future of work shouldn’t simply engage employees in a one-off re-envisioning of their work and work processes and practices, moving the organization and workers from a before state to an after, at which point they return to routine execution mode. Instead, the creative, imaginative identification and solution of unseen problems/opportunities will be their primary work. That means sustained creative opportunity identification, problem-solving, solution development, and implementation—work focused on continuously creating more value to internal and external customers, suppliers, partners, and others.

The (human) work of the future

The opportunity to redefine work isn’t about skills; in our view, skills are too narrow. 2Reskilling people to do a different type of routine task or to use a new technology to complete the same tasks doesn’t fundamentally change the problem for workers or capture the potential for companies. The same can be said of moving people into an adjacent part of the organization that hasn’t yet become subject to automation or moving a few standout workers into management or product design positions. Only redefining work itself has the potential to expand value for companies, customers, and workers. It requires cultivating and drawing on intrinsic human capabilities to undertake work for fundamentally different purposes (see figure 2).

We all have these human capabilities. Unfortunately, many of our institutions generally limit our ability to exercise them so, like muscles, they atrophy with lack of use. Then again, why would workers exercise these muscles? What would motivate them to make the extra effort and potentially take on extra risk when they have been expected, even rewarded, for letting them atrophy in the past? A leader can provide context and latitude, but if workers aren’t motivated, they likely won’t act effectively. This is where passion comes in.3 Workers who are passionate, who have what we call the passion of the explorer, are driven to take on difficult challenges and connect with others because they want to learn faster how to have more of an impact on a particular type of issue or domain. This type of passion is unfortunately rare in the workplace (less than 14 percent of US workers have it), in large part because the tightly structured processes and command-and-control environment of most large companies discourage it, often explicitly.

Job of the future: Mobility platform manager

Mobility platform managers (MPMs) oversee a city’s integrated transportation network, ensuring the seamless movement of people, vehicles, and goods. During daily traffic, they visualize data, monitoring demand and supply across various modes of transport, using an AI-powered system to optimize routes and pricing, intervening when human judgment is required. To prepare for disasters, they use predictive models to help plan how to allocate resources and adapt quickly to the ebb and flow of traffic. In addition to traffic efficiency and minimizing damage to the environment, MPMs are responsible for public safety, accessibility, and equity within mobility systems. They coordinate with stakeholders in the public and private sectors to conduct scenario analyses and assess the feasibility of proposals, and stay up to date on advances in their field through integrated microlearning tools and attending peer meetups and conferences.

For more, read the article by William D. Eggers, Amrita Datar, and Jenn Gustetic, Government jobs of the future, on www.deloitte.com/insights.

Part of redefining work is defining it in such a way that it cultivates questing and connecting dispositions and helps individuals discover and pursue the domains where they want to make a difference. Organizations that can cultivate and unlock that passion will tap into the intrinsic motivation of their workforce. Employees who are intrinsically motivated to take on challenges, to learn, to connect with others to make more of an impact that matters—those are employees who will act like owners. And while acting like owners and focusing on value creation may also imply changes to compensation and reward systems, no extrinsic reward or perk can compete with the power of connecting with people’s intrinsic motivation when the goal is to have individual workers acting with latitude to the company’s benefit.

Fortunately, work that demands creativity and improvisation and rewards curiosity will likely be more stimulating and motivating than following a process manual. By creating an environment that draws out worker passion, employees will be more likely to begin exercising and developing their human capabilities as a means of having more impact on the challenges that matter to them.

Job of the future: Criminal redirection officer

Criminal redirection officers (CROs) help reduce prison populations by refocusing criminal justice on reformation and rehabilitation. Using enabling technologies and their knowledge of human behavior to achieve superior outcomes, CROs work with low-risk and nonviolent offenders who are allowed to live at home and go to work instead of being housed in prisons. A suite of digital tools helps CROs monitor each offender’s physical location, proximity to other offenders, and drug or alcohol use, as well as ties to community, family, and employment to ensure compliance with program requirements. In addition to monitoring time served, CROs equip offenders with the necessary skills, resources, and behaviors to successfully rejoin society and prevent recidivism, and use historical and real-time data through AI and analytics-based tools to inform action plans. CROs have regular virtual check-ins with their charges and other stakeholders, using gamification to encourage prosocial behavior and help offenders achieve goals.

For more, read the article by William D. Eggers, Amrita Datar, and Jenn Gustetic, Government jobs of the future, on www.deloitte.com/insights.

Getting started

Redefining work at a fundamental level across an entire company is no small feat. If we take the opportunity, it changes everything and everything must change. It implies a major organizational transformation.

As companies begin to identify the need to redefine what work is, they will find they also need to redefine how they think about where work is done, how it gets done, when it is done, and who will actually go about doing it. Companies will need to consider how to cultivate the capabilities of curiosity, imagination, creativity, intuition, empathy, and social intelligence. Management systems, work environments, operations, leadership and management capabilities, performance management and compensation systems, and other human capital practices will all need to change to support redefining work across the organization. It’s worth repeating that redefining work is a goal, not a process—the intent is not to create another rigid process or management theology in your organization. Instead, seek to minimize the number of routine tasks that workers must perform, and maximize the potential for fluid problem-solving and addressing opportunities to create value for customers and participants at all levels of the organization.

Fundamentally redefining work is more than a nice-to-have—it’s imperative to remaining competitive. Moreover, it’s an opportunity to shift the future of work conversation from one based on fear and adversity (institutions versus individuals) to one centered around hope and opportunity (in which both institutions and individual workers win). As organizations capture more and more value through a workforce that continually identifies and addresses unseen problems and opportunities, individuals will likely benefit from having greater meaning and engagement in their day-to -day work, igniting more worker passion over time. What are you waiting for? Work is ready, today, for your organization to redefine it.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.

Explore the issue

-

The digital banking global consumer survey Article6 years ago

-

Can we realize untapped opportunity by redefining work? Article6 years ago

-

The Industry 4.0 paradox Article6 years ago

-

Tax governance in the world of Industry 4.0 Article6 years ago

-

Regulating the future of mobility Article6 years ago

-

Seleta Reynolds aims to bring 21st-century mobility to a city built for cars Article6 years ago