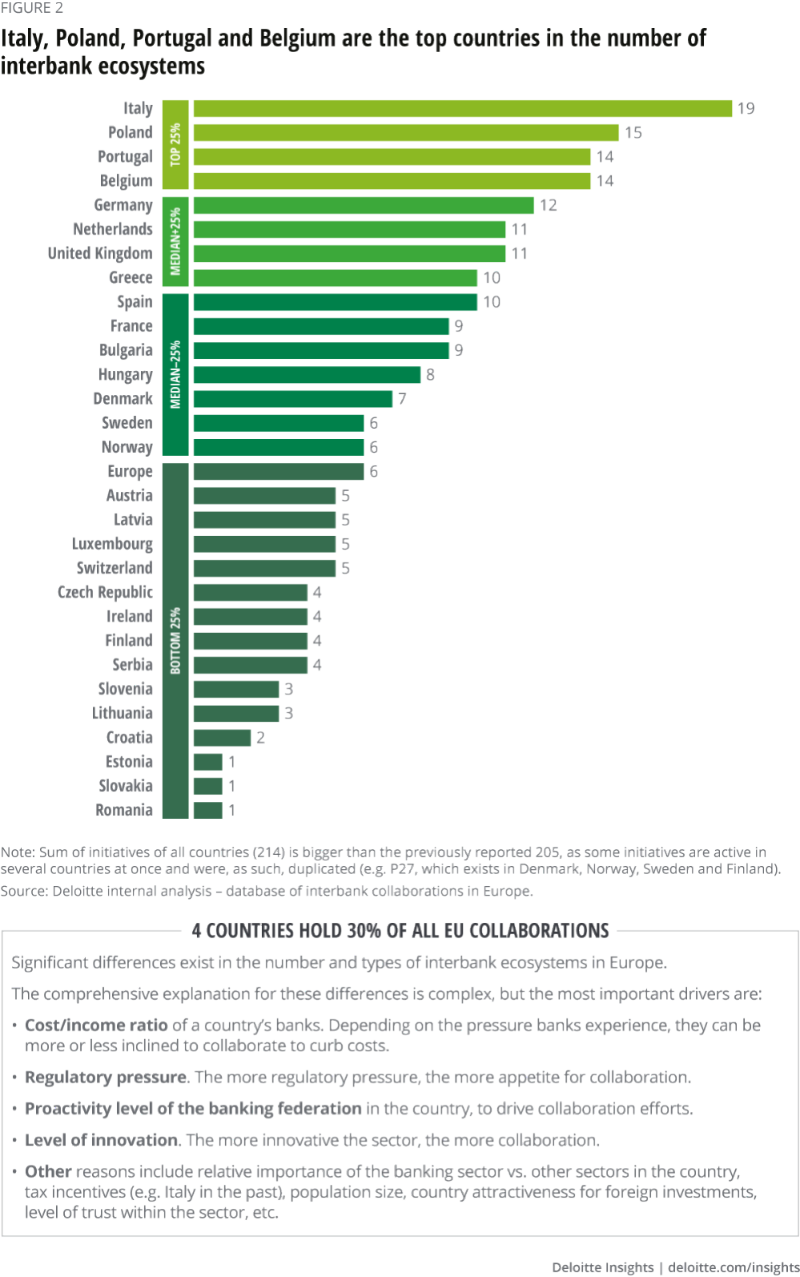

Differences in performance between countries can mainly be explained by variations in cost and regulatory pressures, how proactive the country’s public authorities and/or banking federation are, the degree of innovation in the banking sector, and the level of trust between the executives of different banks. The higher these five factors, the more it can be expected that interbank ecosystems will form.

Recently, the role public authorities play has become more crucial in the initiation of interbank ecosystems. In 2020, the public authorities were, for example, directly or indirectly involved in about half of the ecosystems created that year. European authorities increasingly consider interbank collaboration to be important for geostrategic reasons in the power struggle between the US, China and the European Union. This is clearly the case for the European Payments Initiative where the EU has taken a more assertive stance in the global battle for mobile payments dominance.

Despite the EU’s economic integration, interbank ecosystems have difficulty scaling beyond their country of origin. Only ten of the identified ecosystems were able to achieve a significant European (or global) reach. The differences in regulatory, legal and/or tax regimes represent major hurdles for scaling. It is, however, also clear that the lack of European-scale ecosystems reflects the absence of integrated European banking groups.

So far, only ecosystems in domains that are very international by nature, such as securities trading or trade finance, have been able to transcend national borders. We.trade, a blockchain-based trade finance platform active in 11 European countries, is one of the few examples.

If banks want to succeed in creating European ecosystems, they should design them from the start with European ambitions and interoperability standards. In addition, the regulators should integrate interoperability requirements as early as possible.

The future of Interbank ecosystems: Expansion and consolidation

We expect the number of interbank ecosystems to continue to grow, fuelled by seven broad areas where the ecosystems are only in their infancy now.

Financial crime

Given the increased focus of regulators on financial crime as well as the high cost of non-compliance, we expect banks to strengthen their collaboration in this area. This needs to happen on the European scale, since financial criminals will seek to exploit the weakest banks and countries in the system. Combining transaction and client data at the European level will make the fight against financial crime much more effective and efficient.

Sustainability

Sustainability requirements represent significant additional costs for the banking sector. Investment funds must provide more transparency on their investment policy and respect environmental, social and governance (ESG) criteria. Traditional retail banking activities such as lending are also affected. For example, banks are required by regulators to consider the energy performance of real estate in their lending policies. By creating – potentially in collaboration with public authorities – a common database of Energy Performance Certificates (EPCs), which describe a house’s energy consumption, they can avoid duplicating their efforts.

Digital identity and cybersecurity

We analysed 12 digital identity schemes partially initiated by banks, often in collaboration with telcos and/or governments. Interoperability and European scaling, we found, are high on their agenda, as competing identity schemes initiated by Big Tech conquer the market.

Closely linked to the question of digital identity, cybersecurity costs are rising so fast that banks, especially smaller ones, will be forced to hunt for economies of scale. So far, very few successful examples have emerged.

Financial and digital inclusion

The financial and digital inclusion domain accounts for less than two per cent of the initiatives identified in Deloitte’s Interbank Ecosystem database. For an individual bank, it is quite challenging to invest and innovate in client segments with special needs that are, in general, limited in size. Interbank collaboration, such as, for example, on development of an easy-to-use app or digital assistant, based on artificial intelligence and speech recognition, for people with special mental or physical needs, could be a strong accelerator.

Administrative simplification

E-government has made significant progress over recent years, but true end-to-end digital flows for citizens, SMEs and large corporates will require collaboration between public authorities, banks, notaries and others. We identified several innovative examples of administrative simplification for the creation of SMEs in, for example, Poland and Hungary, but much more can be delivered.

Data hubs

The future will be based on artificial intelligence, with data the electricity for new services and products. Banks are, however, not leveraging the data they have as effectively as Big Tech due to their legacy systems and lack of data culture. They are also not used to integrating external data in their service delivery. Data hubs could provide an answer. Here the objective is the collection, centralisation and sharing of non-banking data across banks – for example, data captured via the Internet of Things. It is possible that banks will acquire or create independent data providers in the near future.

Beyond banking services

Deloitte’s Digital Banking Maturity 2020 study, covering more than 300 banks, clearly revealed the gap between digital champions and other players in the market. Digital champions integrate beyond banking services in their banking apps (e.g. buy a train ticket in the app, receive discounts in shops). The followers and laggards in the market, due to limited scale or budget, will need to develop ‘white label’ solutions to keep up with the more advanced players. This could also be achieved through interbank collaboration.

In parallel with the growth in the number of initiatives, we expect consolidation in existing interbank ecosystems. Today, we see a myriad of initiatives that will be brought under one consolidated roof in order to streamline interbank activities within a country. The merger of the payment and identity services, Vipps, BankID and BankAxept, in Norway is an example of a multipurpose ecosystem in which collaboration initiatives from different domains are clustered. SIBS, Portugal’s interbank joint venture, is another example.

Similarly we foresee consolidation of European ecosystems in payments and cash. The demand for cash has decreased significantly, leading to joint organisation of ATM networks. It is likely to continue to drop over the next five years, forcing banks to collaborate still more in order to cover their costs. Further consolidation of ATM networks is the likely answer. At this moment, Belgium, Luxembourg, France and the Netherlands have all engaged in ATM collaboration initiatives, but in the future these initiatives can be consolidated (e.g. by a commercial player). In the mobile payments domain, it is evident that not all country-based mobile payment providers will be able to survive independently in a globalising market. It is possible that some of them will adopt a buy-and-build strategy or that a European or global commercial player will consolidate them.

Conclusion: It is time for banks to collaborate, fast

Bank CEOs are torn between two goals; the innate urge to compete and the realisation that collaboration is a necessity. But banking is at a transformative point, and banks do not have time to spend years defining and then implementing ways of collaborating with one another and with Big Tech.

By joining forces quickly, opening up to other sectors and to public authorities, banks can build credible ecosystems that will enable them to prosper and benefit both their clients and society as a whole.