Confronting the crisis How financial services firms are responding to and learning from COVID-19

13 minute read

30 April 2020

FSI firms are learning valuable lessons in crisis management and contingency planning as they battle the COVID-19 pandemic. Here’s a look at several firms’ plans for the near future and for the long term to help them build resilience.

View sections

Getting through it to get stronger

Since the beginning of 2020, financial services firms around the world have been responding to the COVID-19 pandemic by relying on not only existing crisis management and business continuity plans, but also institutional memory, creativity, and plain hard work.

Learn more

Learn more about connecting for a resilient world

Learn about Deloitte’s services

Go straight to smart. Get the Deloitte Insights app

Early indications suggest that not all financial services institutions are leveraging their plans in the same way. One survey indicates that only about a quarter of financial services firms relied on existing business continuity plans to manage through the early days of the crisis. About 40 percent used modified plans and a third created new ones on the fly.1

Firms with a wide geographic footprint had a distinct advantage in mounting their response. They were able to learn from their experiences in Asia and Europe, which faced the pandemic earlier in the year.2 One firm, having undergone multiple fraud and financial losses, had more well-documented and stringent operational controls. A bank that had recently suffered a prolonged technology outage had already accelerated its shift to digital capabilities.

With that in mind, using a combination of our own work with clients and a survey fielded in mid-April (see the sidebar, “About the survey”), we will begin to outline what many firms have learned in the still-early days of this global event. We will also outline some of their early expectations of what scenarios may emerge in the short-to-medium term as the industry shifts from respond to recover and, based on our view of resilient leadership,3 offer some actions industry leaders can consider now to position themselves to thrive in the future.

Sections

Faced with the need to improvise on the fly, firms are learning some hard lessons

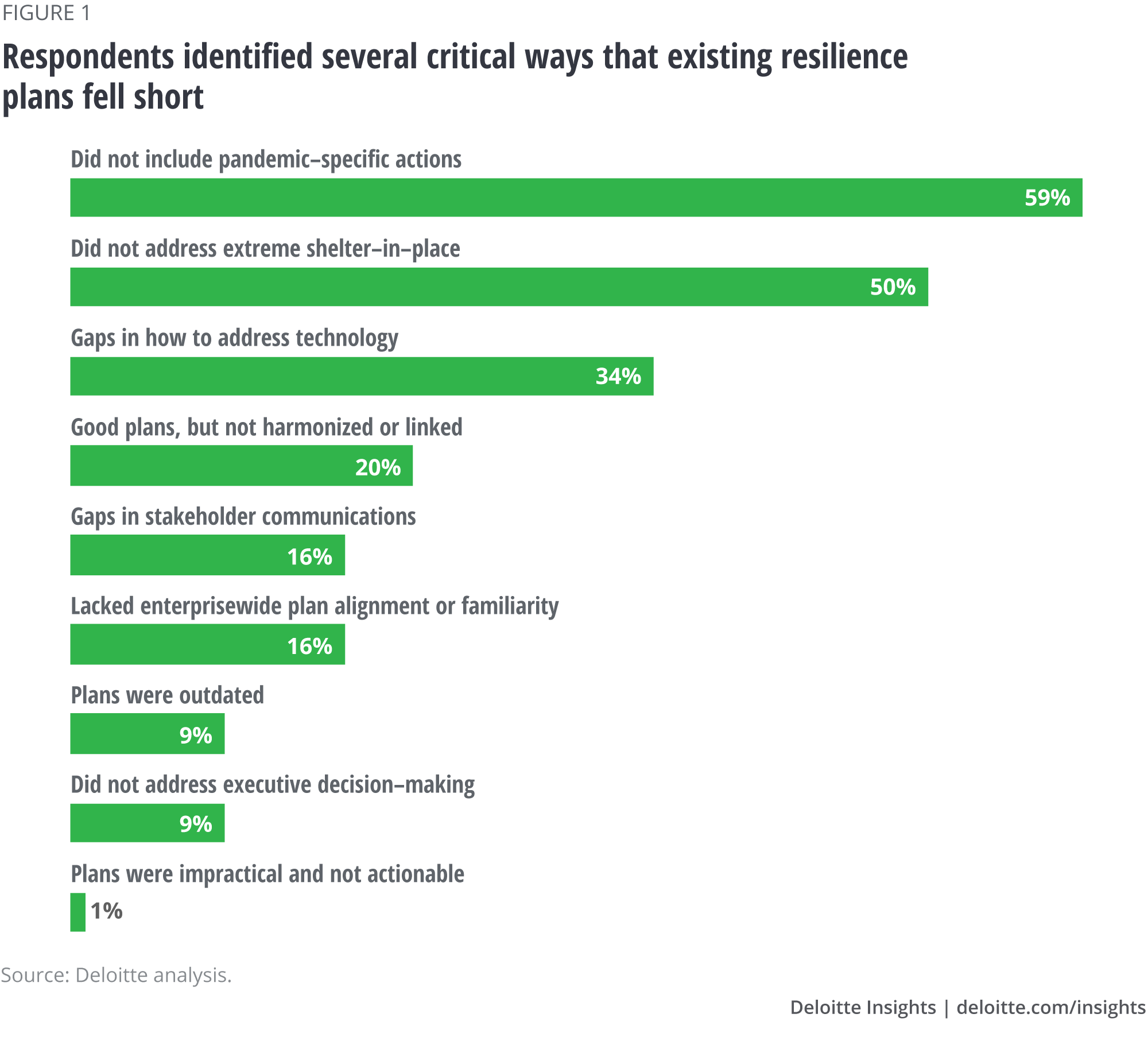

While nearly three-quarters of our survey respondents felt that their firms were better than moderately prepared to handle the impacts of the crisis, only 16 percent felt their response plans worked well. Not surprisingly, the most common gaps were in the plans’ ability to anticipate responses specific to a global pandemic along with shelter-in-place orders (figure 1).

While nearly three-quarters of our survey respondents felt that their firms were better than moderately prepared to handle the impacts of the crisis, only 16 percent felt their response plans worked well.

Respondents also cited technology challenges, especially when it came to dealing with increased trading volumes and demand for loans as a result of the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act (CARES Act).

About the survey

The Deloitte Center for Financial Services fielded a flash survey of senior executives in the US financial services industry with responsibility for crisis management and business continuity planning at their firms.

The survey was fielded from April 17 to 21. Of the 100 responses we received, a quarter were from C-suite executives and the remainder from other senior executives, ranging from director to executive vice president.

This survey is intended to provide information regarding respondents’ thinking across a variety of pandemic-related topics. It is not, nor is it intended to be, scientific in any way, including in its number of respondents, selection of respondents, or response rate. Accordingly, this report summarizes findings for the polled population but does not necessarily indicate industrywide perceptions or trends.

Few plans focused on pandemics

In the aftermath of a variety of crises over the past 20 years, financial services companies became more serious about resilience planning, and business continuity plans have steadily evolved in prevalence and maturity as a result. But, as leaders might find it easy to rationalize, while 9/11 or Hurricane Katrina or Japan’s 3/11 might have had limited impact on firms, or even did not apply to them because of their location or sector, none could predict, let alone escape, the impact of COVID-19.

Because of the ambiguity of the onset and duration of the crisis, companies were unclear as to whether to apply building emergency response, business continuity, or crisis management plans. Existing plans did not contemplate the special precautions needed in a pandemic, and if they did, they were not consumable or actionable and missed the emotional and human effects.

There were also data issues. Firms had to determine the most critical business services for resource prioritization but were faced with a lack of planning for continuity of critical services and a central data repository to aid in decision-making. Ideally, such a database would have included not only critical business services, but also skillsets and site dependency and geography considerations. In one case, data was available but stale. As a result, manual research and analysis was needed to fill the gaps. And when it came to ringfencing locations, where some corporate security leaders might have had the relevant employee and guest information, these departments were often disconnected from senior leadership who were driving the decisions.

Because of the ambiguity of the onset and duration of the crisis, companies were unclear as to whether to apply building emergency response, business continuity, or crisis management plans. Existing plans did not contemplate the special precautions needed in a pandemic, and if they did, they were not consumable or actionable and missed the emotional and human effects.

Shift to extreme shelter-in-place had a global impact

There was a wide variation in the time firms took to adjust to shelter-in-place orders as they rolled out across geographies. In some cases, FSI firms were able to triple the number of staff enabled with remote access over a weekend. For many more, however, shifting thousands of associates to home-based work took several weeks, and some are not there yet.

These issues were compounded when work-from-home orders hit other countries where major offshore facilities are located, such as India and the Philippines. The reality is that most businesses were not set up for offshore staff to work from home; in fact, most BPO firms are only authorized to serve clients from their office location (i.e., clean rooms). In many major cities around the world, the challenge was to ensure a secure environment as people shifted to home-based work under crowded living conditions.

Technology capacity and flexibility put under stress

Technology impacts also arose from the scale and scope of the event. For example, broker-dealers and exchanges found themselves scrambling to process US$1 trillion worth of transactions overnight, about four times the volume ever planned for; capacity had to be quickly added. Firms that had a mature cloud strategy were better positioned to handle the shift. In some cases, manual processing had to fill in the gaps for a variety of tasks, such as trade settlement fails, where volumes rose by two to three times the normal levels. Market utilities struggled to know whom to call to work through the enormous transaction backlog that had accumulated. It took over a week to develop what is essentially a “master rolodex” for that ecosystem.

As workers were sent home, many firms struggled to supply them with laptops and home-based network access. For specialized roles, such as trading, moving from turrets to either one screen or a mobile phone at home impacted productivity and capacity, as did the need to record calls using remote conferencing technologies. Some firms took to staggering remote login times until network capacity was expanded, but were able to maintain a stable operating environment nonetheless.

Gaps found in communication and executive decision-making

Survey participants also identified gaps in plan coordination and alignment and executive decision-making. Stakeholder communications were also cited as deficient; some firms struggled with disseminating consistent information that enabled better decision-making.

The most effective leaders visibly prioritized employees’ and clients’ health and safety or a no-layoff or dividend policy. These north-star mission statements helped align and focus the firms’ response across businesses and functions. C-level executives often led the charge, but personal attributes and experiences probably played a bigger role than functional expertise. Those with a command-and-control style; a detail-oriented, meticulous approach; or knowledge of the firm’s risks and prior experience with crises demonstrated a bias to act, a tendency to take nothing for granted, and a steady hand in handling the crisis.

But even when senior leadership was quick to organize, activating the rest of the extended response team was a challenge. In one firm, the executive team created its own situation room, separate from the protocols and plans of the crisis management and business continuity teams, which may have caused gaps and slowdowns in their response.

Communication of firms’ decisions and protocols to external stakeholders differed depending on which level or business unit was relaying the message. One large firm divided its client portfolio and assigned executives to call each client to provide assurance. In another case, a leader made statements to investors only to have to modify commitments as the crisis unfolded. Employee communications and support have also been critical. One firm appointed a senior executive full time to ensure employee well-being, including assistance with food and health care.

Controls, supervision, and compliance had to be reconfigured

Underlying all these demands was the need to invent flexible approaches to controls. Many firms were compelled to execute first, and then figure out how to control risk, both old and new.

Underlying all these demands was the need to invent flexible approaches to controls. Many firms were compelled to execute first, and then figure out how to control risk, both old and new.

Supervisory controls and control structures are harder to implement in a home-based work environment. Worker supervision needed to be examined anew from a controls standpoint, whether it was the use of nonauthorized applications or conflicts of interest—for instance, where other residents in the home might be exposed to confidential information or even work for another firm that might be a counterparty in a transaction.

One Wall Street firm presented its controls plan to the board in advance of allowing their employees to work from home, with representation from all three lines of defense. The plan clearly defined responsibilities and controls. In other cases, Compliance quickly signed off on the relaxation of certain requirements allowing remote access, obtaining wet signatures on new account documents later, and deferring certain onboarding vetting requirements since local courts were shut.

Anticipating an uncertain recovery, firms develop contingency plans

Organizations can use contingency planning to outline a sequential course of action. A contingency plan works in tandem with a crisis management plan, which details the process an organization uses to respond and manage through a disruption. Contingency plans focus on near-term tactics and operational activities and differ from scenario plans, which are longer-term and more strategic in nature.4

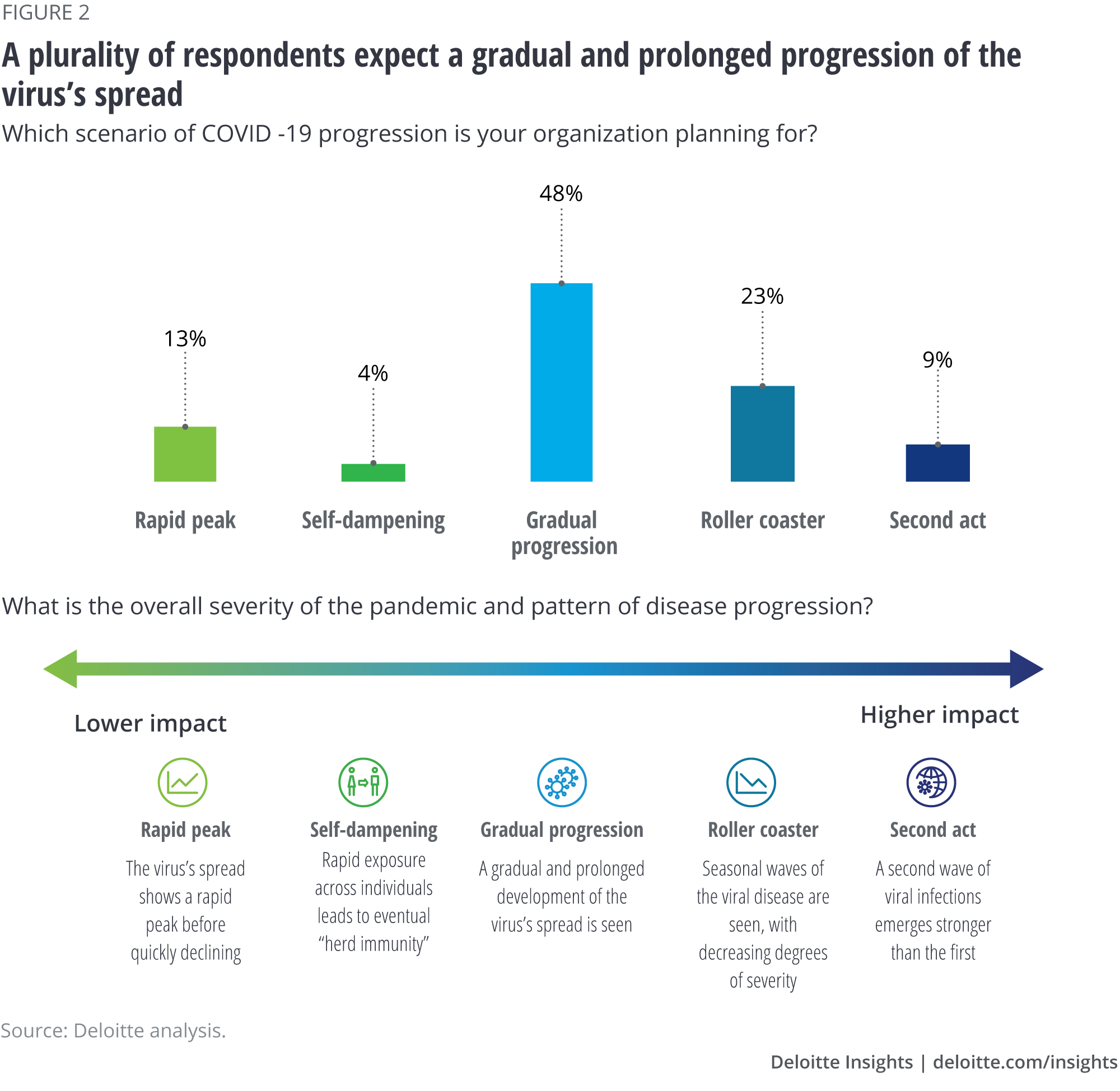

As they plan for upcoming contingencies, most survey respondents expect a gradual and prolonged progression of the virus’s spread (figure 2). But respondents also noted inverse time frames when planning for operational versus financial contingencies. While most are planning for operational contingencies over the next six months, almost 40 percent anticipate the need to extend financial contingency plans for longer than six months. Our conversations with FSI executives mirror this finding: Forward-looking planning activities are just getting underway; time frames range from through the summer to over the next two years. Indeed, some banks are publicly adjusting their stress tests to consider more extreme scenarios.5

One firm is dividing its approach into two teams: One takes care of its people, another takes care of customers. Its overall approach is conservative; leaders assert that they will not be the first back anywhere. Similarly, another firm is expecting that the hardest-hit areas will be last to return to the workplace, and plan to adopt a “follower” approach in determining who is deemed essential and how they will reopen. Along these lines, another firm continues to plan for up to 40 percent of its staff being unavailable to work for some time. Yet another is evaluating the stability of the power grid in India during the summer and its impact on productivity. Across the industry, leaders agree that testing will be essential,6 and returns will be gradual, beginning with those in lower-risk demographics. People with preexisting medical conditions will be the last to be brought back to the workplace.

As they plan for upcoming contingencies, most survey respondents expect a gradual and prolonged progression of the virus’s spread … Our conversations with FSI executives mirror this finding: Forward-looking planning activities are just getting underway; time frames range from through the summer to over the next two years.

Moving forward, stronger: What have FSI firms learned?

As FSI leaders plan for what might happen as society reopens, the real-time experience of such a surprising and prolonged enterprisewide and worldwide crisis has given them a rare lens to use to evaluate and improve their capabilities.

In the immediate term, respondents indicated that their firms developed restart plans that were either role-specific, geography-specific, or a combination of the two. As part of crisis management, firm leaders should anticipate that some employees will be anxious to come back to the workplace. They will need to not only show their people that they are appreciated and valued, but also ask them for suggestions and input on what the best path forward might be. Half of the respondents indicated their firms’ plans to address potential workplace concerns for returning to the office include decreasing workplace density and enhancing cleaning measures.

In the immediate term, respondents indicated that their firms developed restart plans that were either role-specific, geography-specific, or a combination of the two.

When asked about strengthening resilience in the future, about half of the respondents mentioned the need to enhance existing resilience plans. Many mentioned better plan coordination, more frequent simulation exercises, and more comprehensive documentation as priorities. Assessing requirements for critical workloads and reassessing global plan coverage were also top-of-mind.

When asked about strengthening resilience in the future, about half of the respondents mentioned the need to enhance existing resilience plans. Many mentioned better plan coordination, more frequent simulation exercises, and more comprehensive documentation as priorities. Assessing requirements for critical workloads and reassessing global plan coverage were also top-of-mind.

Similarly, we noted above how CEOs had a starring role in how their firms responded, and many are mandating a nimble, action-oriented approach to resilience in the future. Senior leaders, together with their boards, are responsible for ensuring organizational resilience and holding managers accountable. Crisis management, business continuity, and incident plans should all be equally emphasized and not built in silos so that they can work in tandem during an event. Strong governance can enable this alignment. About half of the respondents wished they had conducted a crisis simulation in the past year to better prepare themselves. Indeed, some did: One company that confronted volume surges over the past few weeks clearly benefitted from having run a pandemic planning exercise in November.7 Firm leaders should ensure these exercises go beyond processes to focus on decision-making and exploring the cross-cutting, secondary, and tertiary impacts that FSI firms may face. As a requirement by regulators, developing business continuity plans has often been a “feel-good,” compliance-focused exercise instead of being a truly challenging one. We have now learned that no scenario is too unbelievable.

For any resilience program, the driving principle should be to improve decision-making and create a proactive and agile risk capability. Programs should take a prioritized “business services view” to plan contingencies for critical services, assess impacts, and set priorities at an enterprise level. Before the COVID-19 crisis, most respondents indicated their organizations relied on sources from the government and industry peers to make decisions. Now, FSI firms have an opportunity to create an integrated monitoring process that collectively captures data from different monitoring systems across the organization, such as cyber, fraud, physical security, and reputational sources. Firm leaders need to have better insights and information to make decisions. As scenarios change, they need to modify decisions and understand important variables, the potential impacts of decisions, and even considerations for the next decisions that may be required. This intelligence capability can be used during normal business conditions to anticipate emerging issues as well as during crises to inform agile decision-making.

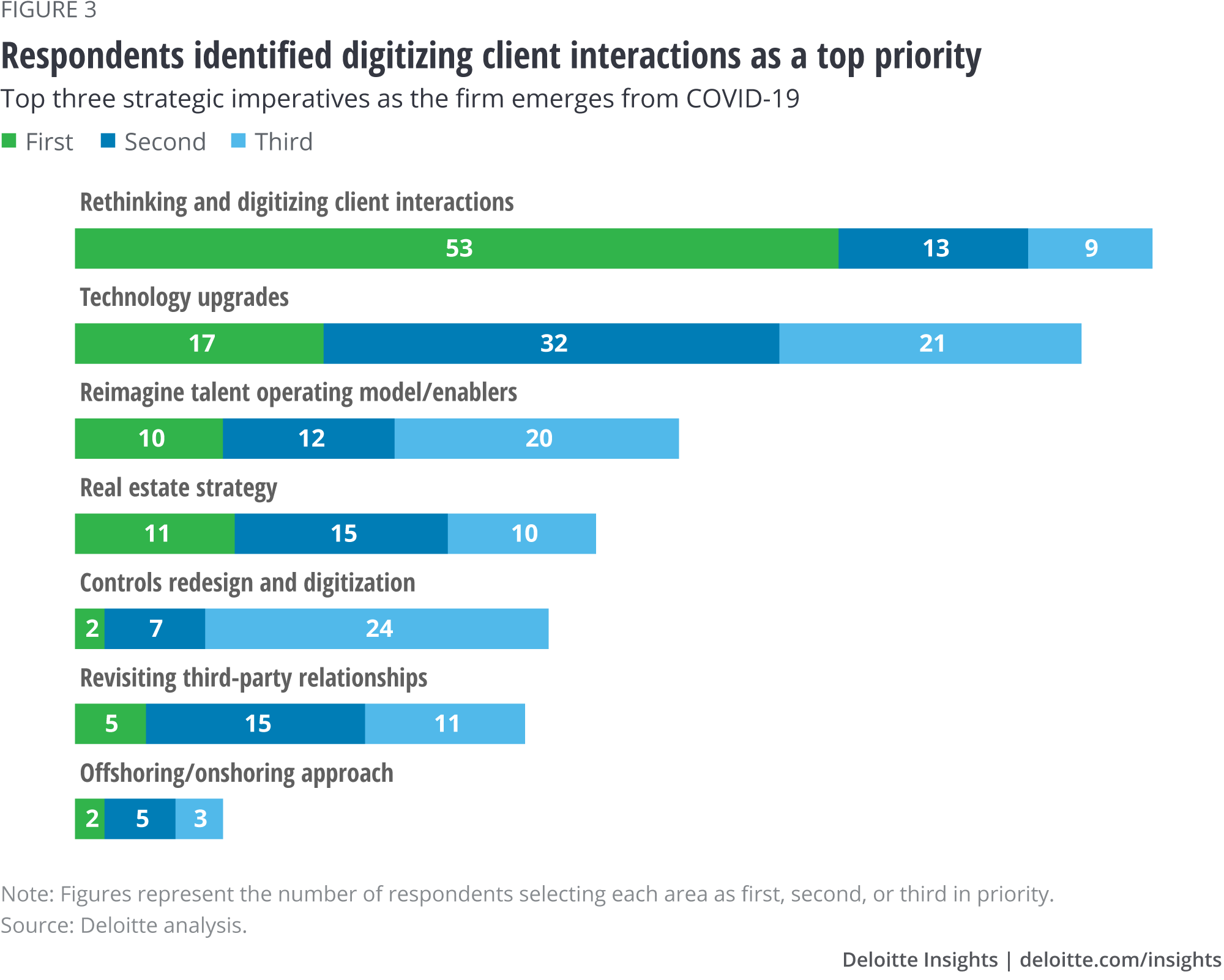

Looking forward, we asked respondents about their firms’ main strategic priorities as the recovery continues (figure 3).

Overall, respondents indicated these were the top three priorities:

- Technology investment. Respondents cited increasing digital capabilities around client interactions, and technology upgrades in general, as top issues. We anticipate a doubling-down on the speed of digital transformation over the coming months and years. These efforts will include increased spending on cloud technology; data center evolution; digitization of client experience, from onboarding to servicing; smart use of tools to improve the agility of response, communication, and reporting during an event; and investments to support more updated business impact analysis data, which will help firms assess and respond to a range of potential future scenarios.

- Future of work. Respondents mentioned the need to both reimagine the talent operating model—what work gets done, and by whom—and their real estate and sourcing strategy—where work gets done. Across firms, various business units and functions will need to codify the practices that were invented during this crisis. These include contingency skills matrices, deeper succession plans beyond the executive suite, and just-in-time staff onboarding and training modules, to name a few.

- Controls redesign. Where does the know-how live inside many FSI firms? Many firms have learned that important knowledge is embedded in people’s institutional memories and 30-year old processes that lack playbooks, many of which are still done manually. Controls will need to be redefined to function with a remote workforce. The most critical controls—process, detective, and preventative controls that rely on improved workflow tools—will be digitized, along with machine learning and visual risk-sensing capabilities.

We will be exploring these issues in more detail in upcoming reports.

Learning from history, in real time

As mentioned earlier, the COVID-19 pandemic has presented challenges that no one in the financial services industry today could anticipate or plan for. That much is clear. And while we hope to recover in the not-too-distant future, we also can use this time to document the lessons learned—both good and bad—to emerge stronger and embed these learnings into plans for whatever challenges may surface in the future. Hopefully, after COVID-19 subsides, there won’t be another global pandemic any time soon. But the actions taken, the responsiveness and agility displayed, and the resilience seen in the everyday actions of so many in the industry will place FSI organizations in a stronger position for whatever may come next.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.

Explore COVID-19 resources

-

Global Weekly Economic Update Article4 days ago

-

COVID-19 potential implications for the banking and capital markets sector Article5 years ago

-

Potential implications of COVID-19 for the insurance sector Article5 years ago

-

Potential implications of COVID-19 for the insurance sector Article5 years ago

-

The economic impact of COVID-19 (novel coronavirus) Article5 years ago

-

US policy response to COVID-19 aims to set the stage for recovery Article4 years ago