Executing the open banking strategy in the United States Engaging with consumers in the journey

16 minute read

21 October 2019

In other countries, open banking has grown due to regulations—but US growth will be industry-driven. Here are some key factors US bank leaders can consider when developing their open banking approaches.

Key messages

- In the United States, open banking is expected to evolve as an industry-driven initiative, unlike other countries, where regulatory mandates are forcing many banks to adopt open banking. However, US banks can benefit from lessons learned in these regions, such as how to establish technical and customer experience standards for data-sharing/APIs.

- If done well, open banking can help US banks achieve key strategic goals. Open banking can amplify and accelerate banks’ digital transformation efforts and the emergence of new business models.

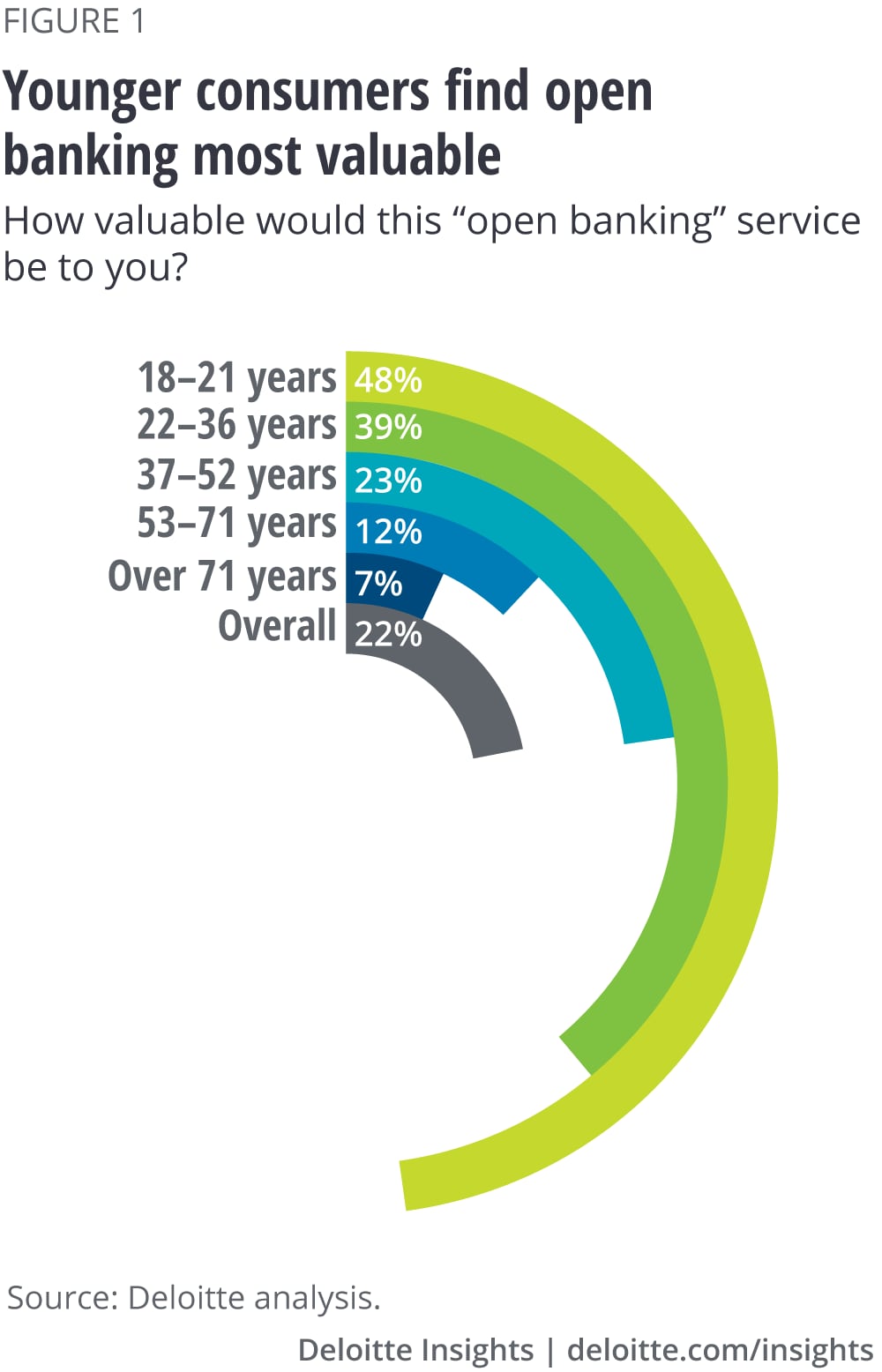

- So far, attitudes toward open banking in the United States appear to be mixed. Our consumer survey revealed one in five consumers in the United States find open banking valuable,1 but the interest is higher among millennials and the Gen Z generation. This suggests US banks should target younger generations in their initial open banking initiatives.

- But consumers also expressed some concerns, especially about privacy, and the security and use of personal data. This seems to point to a need for banks to educate consumers about the benefits of open banking.

- The question, “Who owns my data?” is at the heart of how receptive consumers may be about open banking. Less than one-third of consumers feel they are in control of their financial data, which is a growing source of friction for them. Banks should recognize that the concept of customers as owners (or co-owners) of their financial data will likely soon become a reality, given the global political and social trends concerning privacy and customer data. Allowing for this shift may not only alter the relationships consumers have with their financial institutions; it could also change business models in banking.

- While the potential upside may be vast, the stakes are high. US banks should be selective in how they implement open banking practices. They can take the lead from a position of strength, pivoting from a product-centric mindset to a customer-centric focus.

Open banking: Leading from a position of strength

We are racing toward a future dominated by an open-data economy. Until recently, customer data was zealously kept within the narrow confines of individual organizations. Now, data is quickly becoming more “open” and shared with external parties. Even more important, a fundamental shift is now underway over who has control of this data: It is being returned to the customers who generated it.

Learn more

Explore the Financial services collection

Subscribe to receive related content from Deloitte Insights

Download the Deloitte Insights and Dow Jones app

In several global regions, one of the key ways this shift is occurring is through open banking, which is quickly becoming one of the most transformative trends in the banking world today. Every day, new open application programming interfaces (APIs) are developed to connect banks with other institutions.2 Originally created to allow access to a bank’s network, these open APIs are fast becoming important pipes of banks’ digital infrastructures, enabling data-sharing at greater speed and volume.

In addition to giving customers ownership and control of their own data, enabling customers to voluntarily share their financial data with other entities—a core principle of open banking—has been around for some time now.3 For instance, screen scraping, a method to extract data from a web page using a customer’s login credentials, has been used extensively by many third-party providers.4

While open banking is in the early stages of its evolution, many expect this trend to accelerate and reshape the banking industry in meaningful ways. Thanks, in part, to open banking developments around the world, there is now a new debate about who owns a customer’s financial data. At the same time, customers are becoming more aware of the inherent value of their information and are increasingly seeking more control over their financial data.5

For consumers, sharing their data, in any context, is a sensitive topic. So the questions for banks in the United States are: How receptive are US consumers to open banking? And, How can banks create value by using shared data to meet customers’ latent needs and overcome their concerns?

Open banking versus platform banking: What they are and how they’re different

This report examines US consumers’ willingness to embrace open banking. Our primary evidence is a survey of 3,000 consumers. (Please see the appendix for more details about the survey.) Of course, there are other factors that will likely impact how open banking takes hold, chief among them the technology approaches and strategies banks and fintechs pursue. A separate upcoming Deloitte report will look at the technology aspect, especially the development of APIs and microservices in the open banking and platform banking models, and outline various steps banks can take to potentially accelerate the adoption of these services.

But before coming to our survey results, we want to clarify what we mean by open banking because this term has been used to mean different things. Practitioners around the globe frequently use ”open banking” as an umbrella term that encompasses both open banking and platform banking. But we believe there are important differences.

Open banking is when a bank, upon a customer’s request, shares customer data with third parties via APIs.6 Open banking does not use other, less secure methods of data-sharing, such as screen scraping, CSV files, or OCR-readable statements. There are two types of open APIs: read access, which only gives access to account information, or write access, which enables payments.7 Open banking can be mandated through government regulations, as it is in the United Kingdom and the European Union Second Payment Services Directive (PSD2), or its adoption can be industry-driven, as is the case now in the United States.8 Open banking is built upon the premise that customers own the data they generate and have the right to direct banks to share their data with others they trust. While it was designed to give customers more choice, open banking may end up making customers better understand and appreciate the value of one of their key assets: their data.

Platform banking, in contrast, is a digital marketplace, owned and operated by a bank or another third party, that provides banking and nonbanking services. As with open banking, sharing of customer data happens only with customers’ consent. Moreover, platform banking also requires secure data transmission via APIs. The premise behind platform banking is that banks can serve customer needs and offer services beyond their limited portfolios; it is a strategic response to serve customers better, engender more trust, and retain the customer relationship. Open banking enables and amplifies platform banking.

Will the United States adopt open banking regulations?

The open data revolution is most evident in Australia, the United Kingdom, and other countries in the European Union. Each has explicit regulations (Australia’s Consumer Data Right Act,9 UK Open Banking Standard,10 and PSD2) that require banks to share customer data with third-party providers as per customers’ instructions. Other countries, such as Canada, Japan, and Singapore, are also considering similar regulations. Australia, however, has taken it a step further: It has gone beyond the financial services sector, applying an expansive set of rules on consumer data rights and data-sharing to other industries as well. We do not know yet whether this will be a model for other countries,11 although in the United Kingdom, similar efforts are underway (UK ODI Review).

While the open banking model in the United States may take a different path, US banks can learn valuable lessons by looking at how it has been implemented in more regulatory-driven environments. Bank leaders may find it particularly helpful to review how different regions set technical and customer experience standards for data-sharing.

To date, there are no signs that new open banking regulations are being developed in the United States. In 2018, the US Treasury Department stated that there are significant differences between the United Kingdom and the United States, “with respect to the size, nature, and diversity of the financial services sector and regulatory mandates,” and as such, “an equivalent open banking regime for the US market is not readily applicable.”12 This implies that the US banking industry is likely to pursue an industry-driven approach. However, policymakers and regulators have issued recommendations encouraging banks to adopt best practices. Banks, large and small, are developing APIs to facilitate a safe means to exchange banking data and move away from less secure, screen-scraping methods. For instance, Wells Fargo, Citibank, BBVA, and Capital One have all created developer labs and implemented a number of APIs.13

US consumers’ receptivity to open banking

Consumers see value in open banking, but also express concerns

Our principal finding from the survey is that consumers seem receptive to open banking. One in five consumers find open banking valuable,14with the interest higher among millennials and the Gen Z generation (figure 1). Nearly one-half of Gen Z respondents and 39 percent of millennials see value in open banking, in contrast to only 23 percent or fewer of older respondents. This generational difference could be an important factor for bank leaders to consider as they pursue open banking strategies. Our previous research15 on digital banking, as well as our current survey, indicates that younger consumers tend to use more savings, payments, and budgeting apps, a behavior correlated with interest in open banking.

The main reasons more younger consumers said they were in favor of open banking were “flexibility and transparency” and making things “less of a hassle.” But, generally, consumers are most interested in services that make financial management easier, such as being able to compare bank services, integrate financial data, and personalize budgeting tools. As one survey respondent put it: “It's an interesting idea that a lot of people could probably use to aggregate their financial information into an overall big picture to assess where they stand.”

As for difference in responses by income, our survey showed the group with more than US$250,000 in annual income was most receptive to sharing their financial data and to the open banking concept.

Willingness to share data could be a strong driver of adoption of open banking

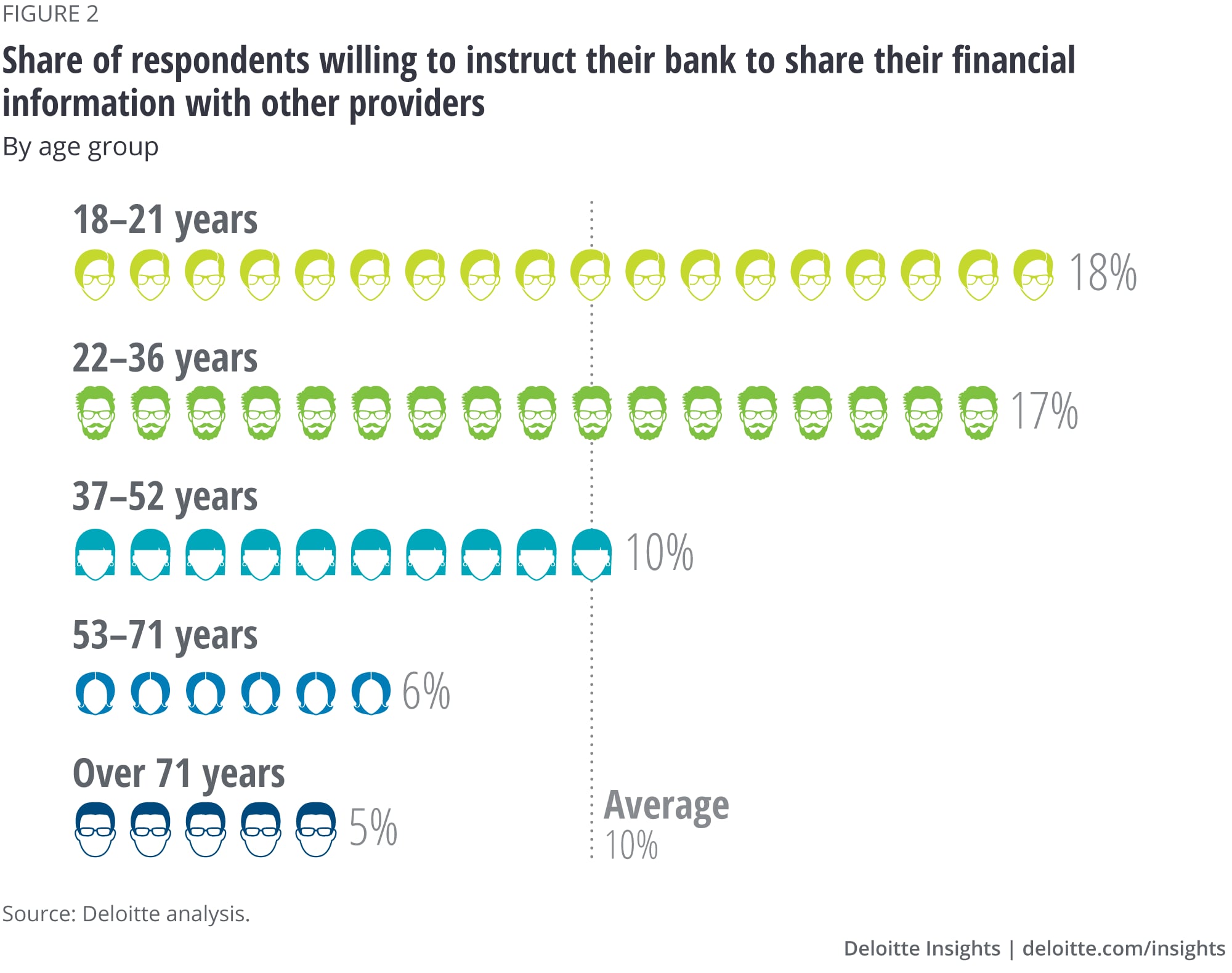

Our survey showed younger respondents are also significantly more likely to instruct their banks to share their financial information with other financial service providers (figure 2).

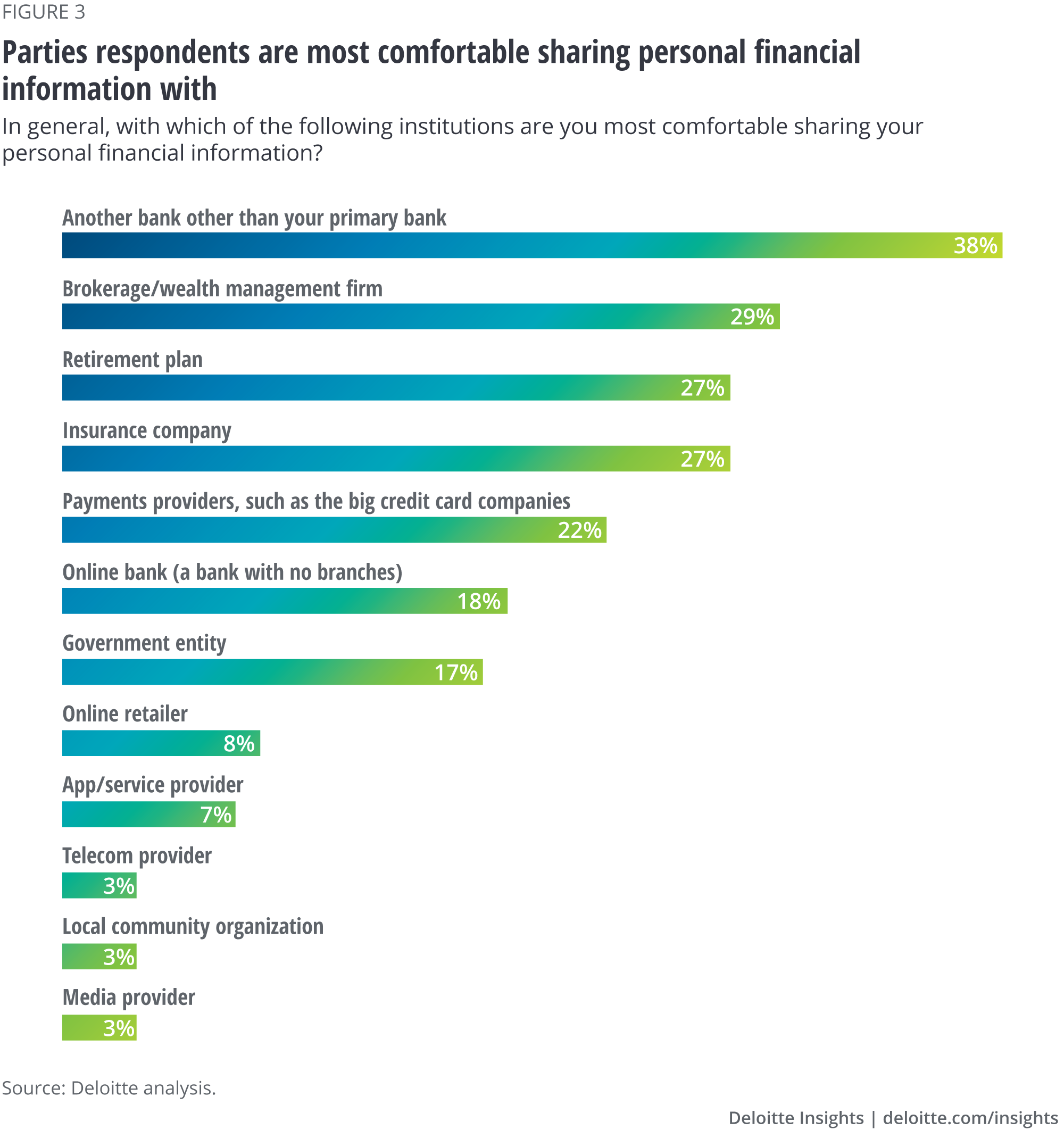

Another notable finding of our survey is that consumers’ willingness to share personal financial information with other third parties is not uniform across institution types. Respondents seemed to trust accredited and established institutions, such as banks and other financial institutions, more than others. Nearly four in 10 consumers cited feeling comfortable sharing their financial information with banks, more so than with online banks or online retailers (figure 3). This should be reassuring to bank leaders.

Trust is an important underlying factor for not only sharing information, but also in building stronger relationships. In fact, nearly nine in 10 consumers surveyed trust their primary bank highly, a fact underappreciated by many, especially those outside the banking industry. Most customers implicitly trust that banks will safeguard their money and their data, and use it only for intended purposes.

Our respondents revealed slightly varying levels of comfort with sharing different types of information. They were most likely to share credit scores, loyalty rewards points, and account numbers. Meanwhile, they were least likely to share more sensitive information, such as investment dollar amounts, personal identifiers such as social security numbers, and account balances.

We also assessed consumers’ beliefs about data control and value. Only about one-third of respondents felt they were in control of their financial data (see figure 4), but nearly one-quarter said they were unsure. Similarly, only about one-quarter agreed with the statement that they would be willing to share their data with financial institutions if they would get back something of value.

Our survey results appear to indicate that if consumers feel more in control, they could be more willing to share data and more receptive to open banking. One way banks could help consumers feel more in control is by seeking consent for each data-sharing request, similar to the open banking regulations in the United Kingdom and Australia. In our survey, 54 percent of respondents said this measure would make them feel they were in control of their financial data. Similarly, ensuring usage for the consented purposes only would make 42 percent feel in control.

Challenges with open banking adoption: Consumer concerns

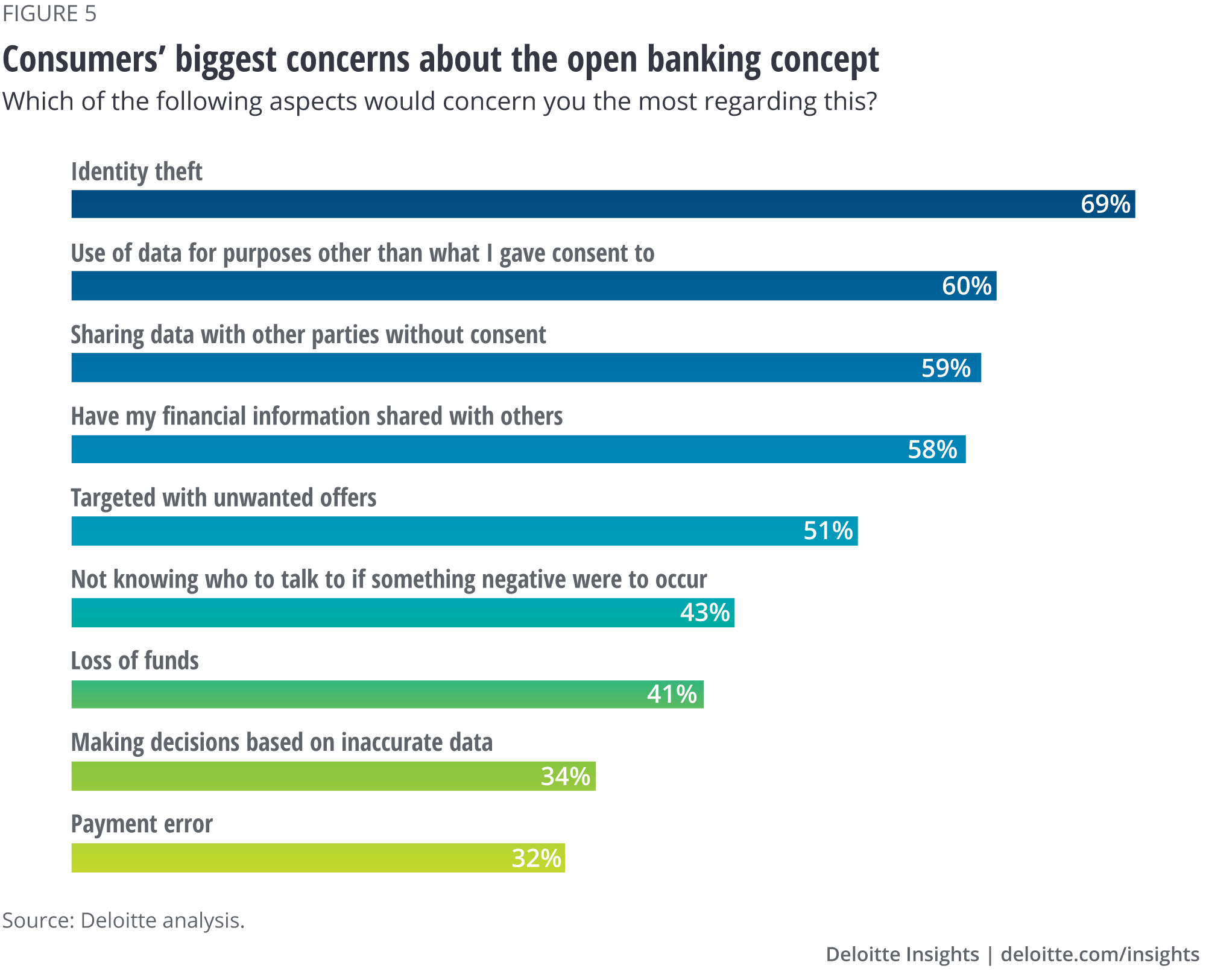

While consumers show interest in open banking, they also express some concerns, especially about privacy, and the security and use of personal data. Respondents called out potential theft of identity (69 percent) and misuse of data (60 percent) as the aspects of open banking that most concerned them. Meanwhile, financial concerns, such as losing money, ranked relatively low (41 percent) (figure 5). The rise in instances of data theft and breaches seem to have made consumers more sensitive about protecting their personal data.

But irrespective of age, the main reasons why most customers are not willing to instruct their banks to share information with third parties are lack of trust in the institution receiving the data and concerns that the data will be misused, shared with others without permission, or lost/hacked. About one-half of respondents hesitant to have their data shared cited these reasons as their main concerns with open banking.

As with overall receptivity to open banking, younger respondents were somewhat less concerned than older respondents, but they also expressed reservations about privacy and security of their financial data.

Adopting open banking: First steps

Before US banks can fully embrace open banking, first and foremost, there needs to be a change in the philosophy about customer data. Banks should recognize that the concept of customers as owners (or co-owners at least) of their financial data will likely soon become a reality, given the global, political, and social trends concerning privacy and customer data. The sooner the financial industry embraces this philosophy, potentially, the better. Armed with this new approach, banks can think expansively and boldly about how to partner with their customers to address their financial needs.

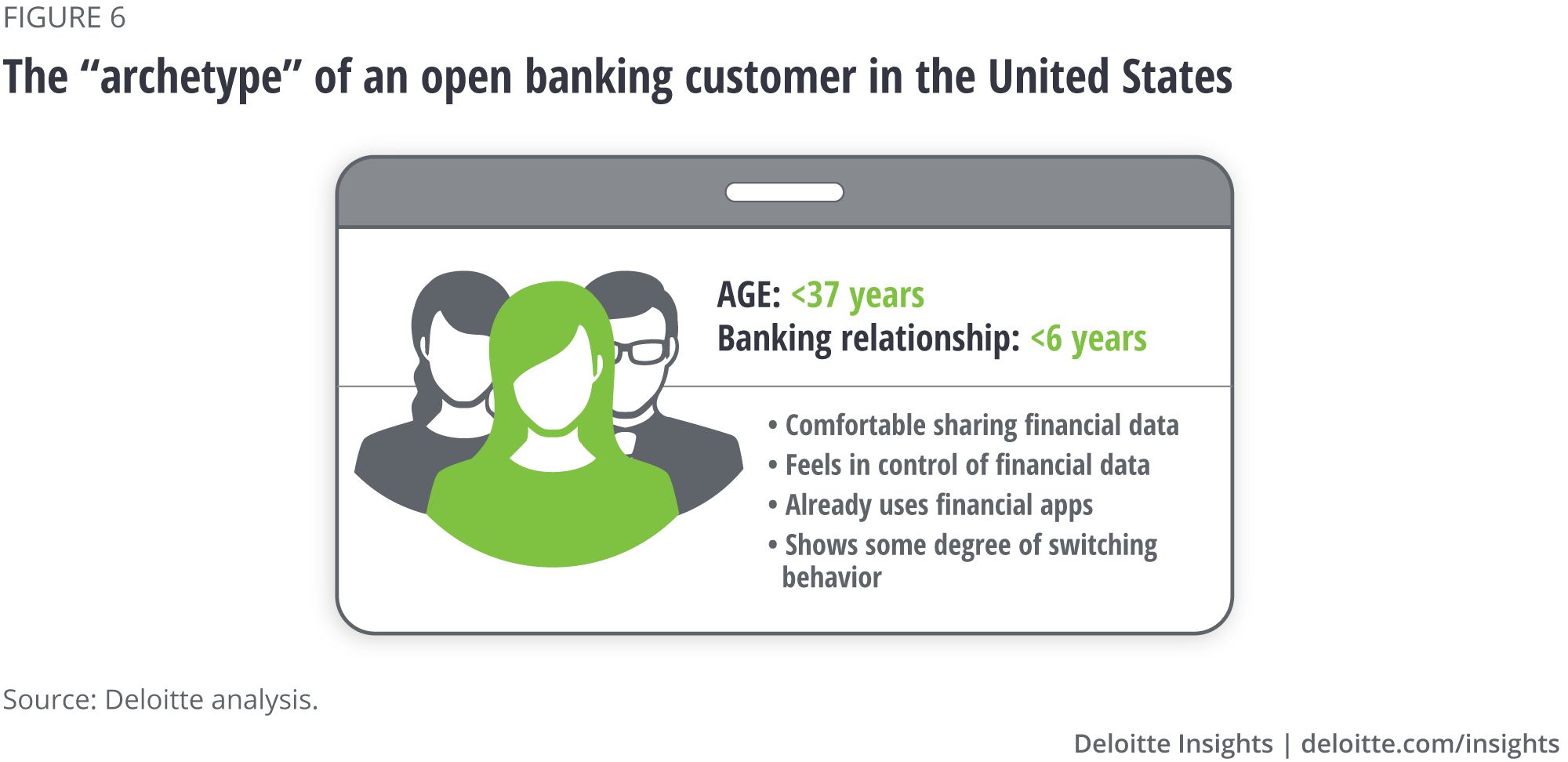

Our survey indicates that in the United States, younger consumers are the prime target for open banking. (See figure 6 for the archetype of a younger open banking consumer.) As a first tactical step, banks could focus on younger consumers and aim to create solutions to meet the needs of this segment.

Given many consumers’ uncertainty and concern about who owns their financial data, banks have an opportunity to clarify and reinforce the view that customers have ownership (or joint ownership). This will likely engender more trust among customers, who, in turn, might be more willing to engage with banks in a more expansive way.

Consumers have a wide variety of concerns, primarily around privacy and security of their financial data. Banks can address these concerns head-on by acknowledging them, revisiting existing policies, and delivering proactive, transparent notifications and communications regarding customer data. These efforts could have benefits that go beyond a bank’s open banking strategy.

More specifically, banks can alleviate consumer concerns to drive the adoption of open banking by following a few key steps. First, banks can give customers a sense of “being in control” by offering a clear opt-in feature for sharing data along with an easy way to revoke consent. They should also proactively communicate these features to customers.

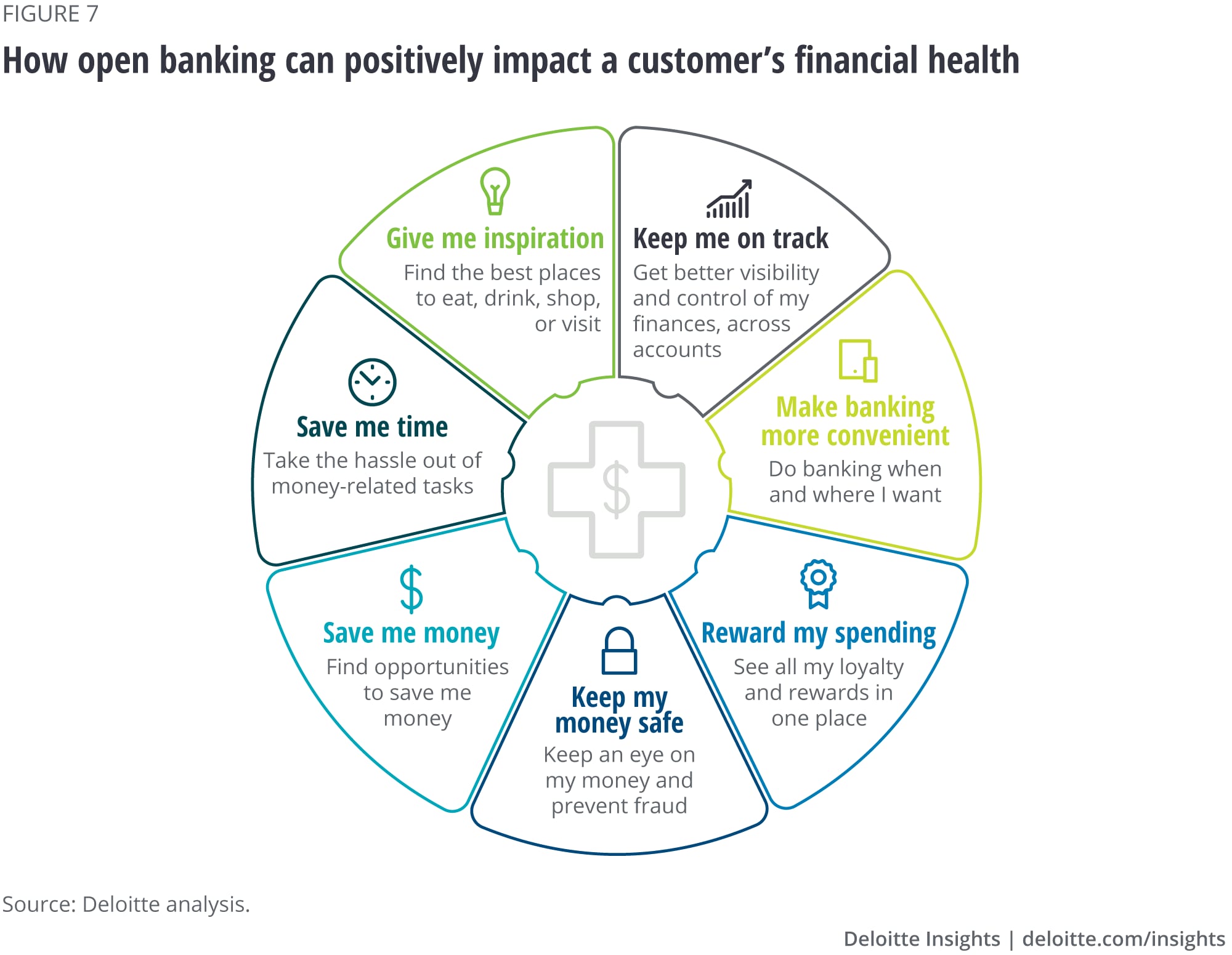

Next, banks should focus on which open banking services would be of most value to customers. Our survey findings suggest that holistic financial indicators, as well as tools to improve financial health, are most desired. While some of these services already exist in the marketplace, expanding and innovating in this area, and making customers feel more in control of their financial destiny, can go a long way toward becoming even more integral to a customer’s life (figure 7).

Banks will also need to determine their optimal partners with whom to create standards for APIs and open banking solutions with the goal of providing a superior customer experience. Banks may want to choose partner institutions that have already engendered a lot of customer trust, including other banks.

Banks should also work with regulators to foster common industry standards for APIs. They should ensure that other regulations related to data security or customer privacy do not inhibit the development and growth of a market-driven open banking approach.

US banks should be selective in their open banking strategies

As highlighted in other publications by Deloitte,16 open banking seems here to stay and is quickly gaining ground outside the United States. More and more consumers are taking advantage of open banking developments in the United Kingdom and Europe,17 and progress has been made on technical standards. While it may be premature for leaders from these banks to point to open banking as a key driver of innovation and competitive advantage, the foundation has been set.

In the United States, on the other hand, open banking is in the early stages, which presents an unprecedented opportunity, especially for early adopters. Here, open banking, along with the broader digital transformation journey that many banks around the world have taken, can help enable the shift from a product mindset to a singular focus on serving customer needs.

US banks can use open banking to recalibrate customer relationships by giving customers control of their data and helping them more easily and confidently engage with third parties for a variety of services. Shifting to open banking may require banks to partner with a broader ecosystem of providers, but banks can still stay at the center of customers’ financial lives by remaining trusted advisers in these arrangements.

How US banks respond to the open banking wave could inform and shape their digital transformation strategies as well. By inserting customers at the heart of the transformation in open banking and beyond, banks can build trust and ensure they remain in a position of strength.

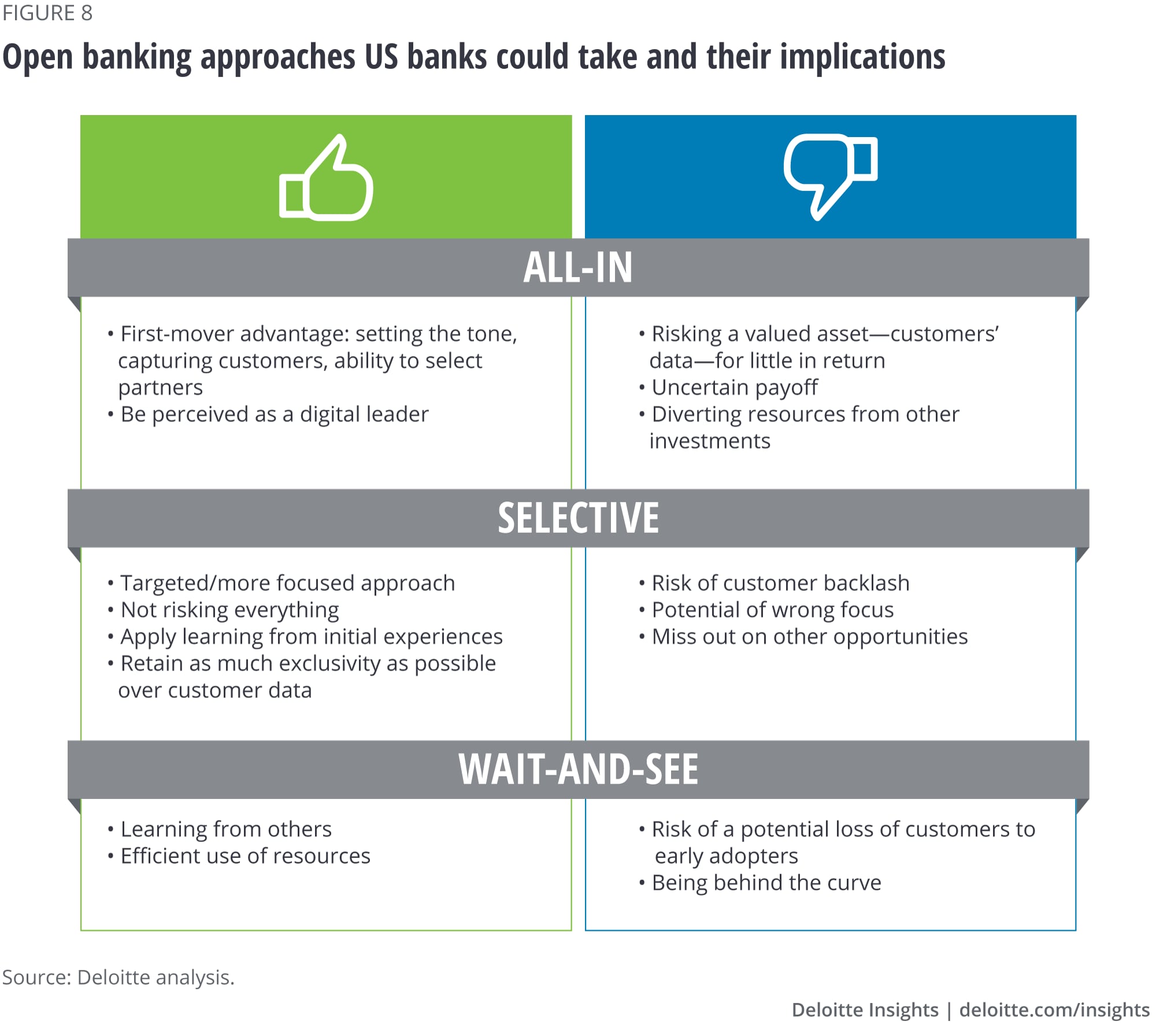

However, there are still some uncertainties about the scale and pace of adoption of open banking in the United States. Should banks fully embrace open banking and accelerate their adoption, or should they be more selective in choosing where to play, or perhaps even wait to see what happens before making a choice? Each approach has its pros and cons (figure 8).

Going “all-in” may yield a first-mover advantage, but exposing the institution to open banking on all fronts, for all products, customer groups, and with all types of third parties all at once may increase some risks. In particular, banks that move too aggressively and quickly into open banking may face customer attrition and may be unable to respond seamlessly to thousands, and possibly millions, of customer requests.

Further, enabling customers to share their financial information with third parties without banks receiving something in return, such as shared revenues or customer referrals, may jeopardize customer relationships and threaten banks’ long-term profitability.

At the same time, sticking to the status quo, and waiting for other institutions to take the lead may also be not desirable; it could result in a lost opportunity. Simply put, customers might prefer to do business with banks that offer open banking.

Although an all-in approach might work for some US banks, depending on their scale and business model, the middle course, the “selective strategy,” may be best suited for most US banks.

A two-way street?

Until now, we have looked at open banking through the lens of banks sharing customer data with other third parties. But open banking can be a two-way street for banks. We have explored banks possibly risking the customer relationship and giving up a precious asset—customer data—to others with possibly no quid pro quo. But there is another lens that is equally relevant: banks as the recipients of customer data from other institutions. For banks, this possibility opens up many opportunities, and would make open banking a two-way street.

Open banking provides banks with an unprecedented opportunity to serve consumer needs more holistically and become even more relevant in consumers’ lives.

And while the future of open banking seems bright, banks need to make the right strategic choices, sooner than later. Otherwise, there is the very real risk that banks will fall behind the open banking trend and cede ground to others more attuned to the times.

Questions US banks should be asking

Open banking is likely to impact multiple areas. Here are the questions banks should be asking within each area:

Strategy

- How can we rethink digital transformation in the context of open banking? This may or may not involve enabling open APIs.

- What types of new ecosystem partnerships should we look for?

Customers

- Which customer needs do we want to serve?

- How well do we understand the dynamics of customer profitability?

- How should we respond to customers who want to share, or have shared, their data with third parties?

- How can we pre-identify customers who are likely to share data with third parties? And with which third parties?

- What standards of customer experience should be put in place when sharing data?

Technology/data

- Do we have the right API strategy and standards in place?

- How can we best mitigate the potential risks of loss and misuse of customer data and inaccuracies in customer data?

- Do we have the right data governance and architecture in place to manage data sharing?

- Do we have the right analytics capabilities in place to enhance our credit scoring, assessment, and decision-making based on shared data?

Appendix

About the study and methodology

The Deloitte Open Banking survey was fielded in April 2019, querying 3,000 respondents in the United States. We set minimum quotas for age and targeted an equal gender representation and an income distribution around a median income of US$75,000. The survey explored how receptive consumers were to the concept of open banking and sharing financial data, and asked about other concerns.

To understand the “archetype” of an open banking customer, we performed a K-means cluster analysis (K=3). A total of 497 respondents (16.1 percent) were clustered as being receptive to open banking. The input data for the cluster analysis included characteristics such as:

- How willing respondents are to share data

- Worries about privacy and data security

- Ownership of data

- Feeling in control of financial data

- Switching behavior for financial and nonfinancial services

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.

Explore the Financial services collection

-

Tapping into the aging workforce in financial services Article5 years ago

-

A moving target: Refocusing risk and resiliency amidst continued uncertainty Article4 years ago

-

Fair valuation pricing survey, 17th edition, executive summary Article5 years ago

-

Reshaping the cybersecurity landscape Article4 years ago

-

Infusing data analytics and AI Article5 years ago

-

The future of the industrial real estate market Article5 years ago