Building regulatory-ready organizations has been saved

Building regulatory-ready organizations Managing regulatory and compliance risk at investment management firms

28 April 2017

As legislation becomes law, asset managers may find themselves consistently on the high end of the regulatory risk spectrum. What proactive and tangible steps can they take to help ensure their firms are set up to succeed, even in turbulent times?

Introduction

Even before 1917, when a case before the Supreme Court referenced speculative securities schemes that had no more value than a patch of blue sky,1 regulatory agencies have attempted to protect investors from fraud, and provided frameworks for fair and orderly market operations.

In the 100 years since, there has been a slow but steady rise in regulatory activity across all industries—leading to the 24,694 pages of final rules published in the Federal Register in 2015.2 As a result, financial regulatory activity is taking up more space on corporate calendars than ever before. A total of 1,371 institutions lobbied the Dodd-Frank bill during the legislative process.3 And after the enactment of the “Conflict of Interest Rule” on fiduciary investment advice, the Department of Labor (DOL) received a record 3,134 comment letters from both institutions and individuals.4

Agency activity around oversight of the investment industry has increased correspondingly (see figure 1). In 2016, the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) reported 868 enforcement actions stemming in part from examinations of 17 percent of investment companies, a record high on both counts.5

Financial firms may find themselves perpetually at the top of the regulatory risk spectrum. In Deloitte’s recent Global risk management survey,6 which covered 77 global financial services institutions representing a total of $13.6 trillion in aggregate assets, more than one-third of respondents (36 percent) highlighted regulatory/compliance risk as among the top three risk types that would increase in importance over the next two years. However, regulatory/compliance risk was even more critical for investment management (IM) firms, with 81 percent citing regulatory risk as a top challenge faced by investment management firms (34 respondents, representing a total of $6.5 trillion in assets under management). Investment management firms are subject to the jurisdiction of multiple regulatory authorities, a factor that contributed to these results.

Legislation vs. regulation

The introduction of a bill marks the beginning of the legislative process which may lead to statutory changes. After a bill is signed into law, agencies decide how it will be enacted, and it becomes regulation.

These regulatory challenges are often multipronged for global organizations across all industries. As one respondent to a global survey explained, “If there is an action or if an enquiry taking place in the UK, for example, then four or five other regulators may also become involved. We are multiply regulated, whether it’s the UK, whether it’s Ireland, whether it’s the US.”7 This means that today, investment managers and distributors with global reach may be finding themselves facing regulatory action across jurisdictions in which they are headquartered and operate, complicating regulatory risk management.

The regulatory-ready organization has three attributes: a framework for risk assessment, a mechanism to track and measure risk, and a method to allocate resources based on its understanding and experience of risks. — Mike Fay, principal, Deloitte & Touche LLP

For IM firms, regulatory readiness is increasingly difficult to achieve. And even in uncertain times, firms will still need to adopt leading practices to respond effectively to a constantly shifting regulatory environment (see figure 2). This paper explores regulatory readiness through a life-cycle framework, from sensing and influencing to prioritizing and planning and then to implementing. Some of these areas are unique to regulatory readiness, and others, such as project implementation, leverage broader-use organizational capabilities. But even these widely used practices have meaningful nuances to effectively manage regulatory change. The focus here is on the peculiarities of regulatory change throughout the life-cycle framework.

Sensing and influencing

Considerations for sensing and influencing the regulatory environment

Given the potential impact legislation, regulation, risk, and globalization can have on a firm’s strategy and reputation, investment firms need to prioritize regulatory readiness. The first way an IM firm can help fulfill this goal is to create an active sensing and influencing agenda that permeates the organization. External-facing activities with lawmakers and regulators could be handled by a government relations strategy. This strategy can help to educate lawmakers and regulators on issues important to the business. Such interactions can also provide greater clarity to the sensing function through the collection of additional information, including intent, political context, and the probability for enactment.

Sensing: Continually monitoring the external regulatory environment to identify potential risks and opportunities to the organization.

Influencing: The process of educating regulators and key individuals in policy making on industry, sector, or organization perspectives in order to help shape legislation and regulation.

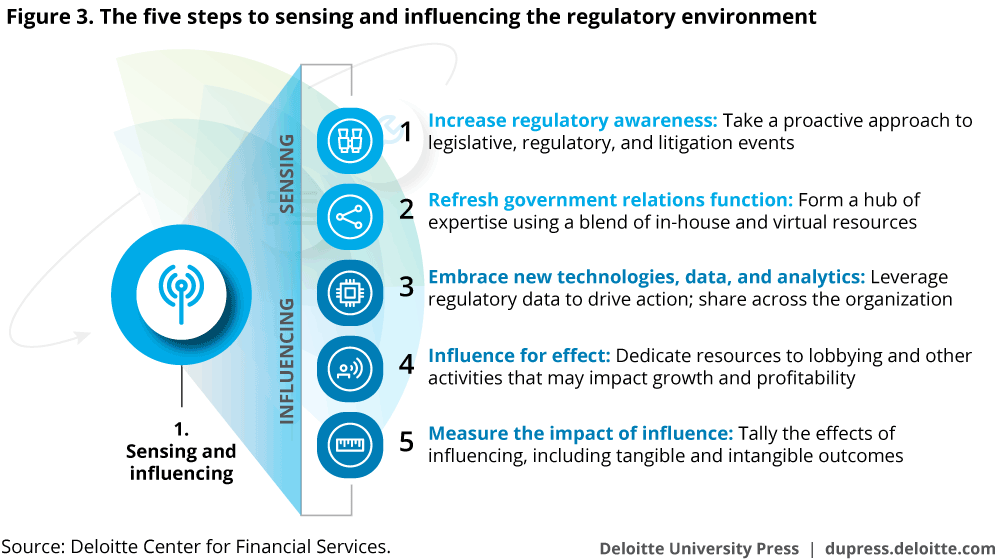

Five steps to sensing and influencing the regulatory environment

So what new approaches should an investment manager take to keep ahead of legislative and regulatory developments? While these will vary depending upon each organization’s strategic goals, the following overall practices may help as outlined in our five-part framework, illustrated in figure 3.

1. Increase regulatory awareness

According to a popular adage, “There are three types of people in the world: those who watch things happen, those who make things happen, and those who wonder what happened.” The same can be said for organizations. When IM firms can review and discuss legislation before it is finalized, they have the chance to shape it and its parameters before it becomes a law.

Regulators can also change their examination priorities, sometimes driven by new business practices and products. In 2017, “electronic investment advice, money market funds, and senior investors” are expected to face increased scrutiny.8 Regulatory-ready organizations often become more well-informed just by listening to regulators talk about what’s on their radars.

Developing a proactive strategy may also yield competitive advantage. One way to learn where competitors are focused is by monitoring lobbying disclosures through its sensing operations. By doing so an organization can get a glimpse into what competitors and other firms are doing. For example, if a competitor is spending time lobbying a certain law or regulation, this may give clues to the strategic importance of the issue at hand. While this process would require looking through a lot of lobbying data, regulatory data providers can help ease this burden.

Government relations teams in IM firms coordinate legislative efforts by working with state, local, and federal governments, and the organization at large, to further the organization’s goals of an investment manager.

2. Refresh the government relations strategy

Investment managers may reap substantial benefits from having an effective government relations strategy. These benefits may include managing political risk, identifying the political opportunity, promoting and protecting business interests, and providing political intelligence (sensing).

An organization’s approach may also vary depending upon a manager’s size, structure, and business strategy. The majority of larger investment managers often maintain a dedicated in-house team, yet small- to mid-sized firms may leverage external resources for support, as outlined in figure 4.

Having a virtual support team may provide a manager with a greater capability to sense the changing regulatory and legislative landscape. Fortunately, over the past few years a number of regulatory data vendors have sprung up to assist. These vendors—as profiled in Step 3 below—may supplement in-house government relations teams, depending on organizational objectives.

Larger firms often supplement their in-house activities with data vendors, trade associations, and lobbyists on retainer while smaller organizations tend to outsource more of the sensing and influencing approach. This outsourcing approach may be advantageous from an efficiency and brand risk perspective (among others), but relying exclusively on associations can have its limitations. The primary trade associations may focus on issues outside of a particular firm’s concerns, or there may be a gap in focus where a firm’s organizational objectives are not addressed. For example, while industry trade associations may cover market structure and investment adviser issues for hedge fund managers, they may not match individual firm priorities in areas such as labor policies, where fund managers may have differing interests.

To keep ahead of proposed legislation, rule enactments, enforcements, and litigation across various jurisdictions, global organizations offering investment products across multiple structures and distribution approaches may need the broadest sensing and influencing scope. Additionally, firms with diverse global product offerings should weigh the disparate impacts that a single regulatory change may have on different parts of their operations.

The sensing group’s connection to the broader organization is also important to consider. Here, it may be beneficial for at least one of the government relations members to also belong to a Regulatory Assessment and Response Execution (RARE) virtual team. This can help ensure that when the externally focused sensing and influencing group identifies a piece of legislation that may impact the organization, touchpoints are already lined up for handing off the issue to internal constituents in the relevant departments that may be impacted.

Since risk sensing should be a valued component of organizational strategy development, it can help if the government relations group has a seat at the leadership table, with appropriate reporting lines based on the IM firm’s organizational structure. This team is already focused on identifying forward-looking, external risks, which are important components of strategic development.

3. Embrace new technologies, data, and analytics

Data and analytics are enhancing the government relations function and creating new information sets that can be used by both dedicated teams and the broader organization. The inception of the eRulemaking program in 2002 seemed to kick off the advanced analytical era by allowing electronic access to pending legislation. Since then, analyst teams have created increasingly robust systems to grab data, analyze it, compare findings to other data sets, and deliver reports.

While larger investment managers may conduct their own legislative analysis, they still may wish to have their work supplemented through outsourcing. Mid-sized and smaller shops, in particular, may benefit from the cost-efficiency of outsourcing data and analytics.

Data and analytics used for government relations efforts may also be leveraged companywide. In light of the growth of these costs, investment managers may want to consider sharing the cost of regulatory data across the departments that may benefit.

4. Influence for effect

History shows that the first American lobbyist was likely William Hull, a Revolutionary war hero who traveled to Philadelphia in 1792 to request back pay for soldiers. (Unfortunately, he was not successful.)9 Since then, the practice of influencing the government has grown considerably.

A government relations strategy also influences for effect beyond direct engagement with policy makers. For example, organizations can conduct grassroots activities, develop media campaigns to shape public perceptions, and interact with third-party groups (think tanks) to strengthen their education efforts.

In addition to lobbying efforts aimed at supporting or opposing a bill during the legislative process, firms also seem to be increasing their lobbying efforts at federal agencies during the rule-writing process and beyond, as demonstrated by the DOL’s Fiduciary Rule.

5. Measure the impact of influence

One of the sticking points to allocating resources to the sensing and influencing functions is the intangibility of the process, and the resulting inability to attribute bottom-line results from government relations activities. Clearly it is difficult to cite influence to outcomes in this area, unless, for example, a regulatory agency sources a comment by a particular manager in a final rule.

Yet there may still be ways a manager can justify budgetary spending for a government relations function:

- Historic reviews of lobbying influence and changed regulation—Data and analytics tracked internally or by vendors may support a time-series analysis of how the government relations function has fared over a period of time. Already, many industry associations track the success of their lobbying efforts; firms can use that as a starting point for tracking their hot-button issues.

- Attributable impact on the bottom line—A number of studies have shown a possible correlation between lobbying and corporate profitability. While results for the investment industry appear to be inconclusive, it is worth noting that political factors may have accounted for an increase in profitability and corporate valuations across a number of industries, particularly since 2000.10 In light of this, investment managers may begin to consider their government relations function in terms of attributed impact to the bottom line, a measure that would distinguish it from being a traditional cost center. One approach might be to award government relations teams with recognition for events connected to regulatory impact, such as when cost-savings are realized or channel-related sales rise after a new rule is implemented.

In summary, the five steps outlined above describe the benefits of an organization creating a coordinated effort around sensing and influencing the regulatory environment. Once these external efforts are in place, a firm can move on to the next phase of being regulatory-ready through internal planning and prioritization.

Planning and prioritization

Once an organization gathers relevant information from the risk sensing stage, the next step is often to follow a structured approach to filter the regulatory signals amidst the noise. A structured and collaborative risk planning and prioritization approach provides dual benefits for investment management firms battling regulatory changes on multiple fronts (product, pricing, distribution, and geographic presence). These include:

- Developing an objective analysis for different regulatory/compliance changes

- Introducing business, product, distribution, and structural changes/responses that align with the strategic plan and vision of the company

However, as investment managers seek to expand their product portfolio and geographic presence, the number of regulatory and compliance risks faced rises exponentially. In a cost- and resource-constrained environment, companies should plan and prioritize their regulatory response to ensure the optimal risk-return tradeoff. In addition to having a core team in place to manage the planning process, the five-step approach described below would help IM firms identify the key regulatory changes that need to be focused on and develop adequate compliance solutions.

Five action points to plan and prioritize in a fluid regulatory environment

A Regulatory Assessment and Response Execution (RARE) team is a cross-functional virtual team in an IM firm that can manage the entire regulatory change and planning process, serving as the key platform that coordinates and manages regulatory change and compliance activities (figure 5).

Its objective is to generate synergies to form a better-coordinated companywide response to regulatory changes. To be most effective, the RARE team should:11

- Have an enterprise-wide regulatory view. This broad view of regulatory change can be used for effective planning, coordination, and program implementation. It typically grows in complexity as organizations operate across geographic and jurisdictional boundaries.

- Interpret and prioritize. Study, learn about, and communicate shifting regulatory trends and their potential impact on business and strategic plans. This helps prioritize the regulatory response effort.

- Conduct scenario planning exercises and risk assessments. Scenario planning techniques could be utilized for regulations having some “unknowns” to identify likely outcomes. For regulations having defined timelines and requirements, IM firms would need to assess their impact before developing the regulatory response. One effective scenario planning exercise can be a moderated workshop that includes the right participants.

- Effectively communicate. To support strategic decision-making, relevant insights and recommendations from the RARE team’s work should be shared with the board.

- Implement across functions. The team should be able to work closely with SMEs (internal and external) to obtain and share the relevant intelligence to develop appropriate regulatory change solutions.

For RARE team members to achieve their expected capabilities, knowledge and communication are two critical requirements. The functional areas for the RARE team are typically finance, operations, regulatory, reporting, extended enterprise, strategic, and technology (FORREST); team members can be expected to have expertise in more than one of these areas. To achieve an enterprise-wide, FORREST view of evolving regulatory risk, team members should also be comfortable coordinating and communicating across levels with different functional areas including risk and compliance, business leaders, strategy, and finance. This capability is important because risk prioritization is often most effective when conducted through a framework that follows a comprehensive path across the organization.

To build a truly multidisciplinary, collaborative, and flexible RARE team, IM firms should spend time developing the right team structure and ensuring that members have the right skill sets for this work. The team structure should mirror that of the firm in terms of organization, degree of centralization/decentralization, reporting lines, position within the three lines of defense model, and linkages to other departments and functions within the risk governance frameworks. Most of the skills typically required to be a part of the RARE team can often be found within the firm, with resources from different areas being pooled together to bring in their functional perspectives to form a virtual team.

After the RARE team is formed, the team would then need to define the responsibilities and reporting lines to ensure a coordinated execution. The following five-step action plan that has the RARE team collaborating with other committees could allow for a more informed approach for regulatory risk planning and prioritization.

Five action points for regulatory change planning and prioritization

1. Mapping current organization’s operating model

Developing a detailed understanding of the business’ current scope and exposure is typically the first step toward being ready to respond to any regulatory/compliance change (see figure 6).

Firms can maintain an operating model, a regularly updated information repository covering the entire financial, geographic, and regulatory scope of the current business. The operating model would include details such as:

- Product portfolio (mutual funds, hedge funds, ETFs, collective trusts, separate accounts, UCIT, CCAV, or others)

- Distribution channels (direct to consumer, commission brokers, fee-based platforms, retirement platforms)

- Client segmentation (retail, institutional, government, others)

- Revenue (split by customer segments, distribution channel, and product type)

- Pricing policies

- Asset class

- Product structure (fund of funds, sub-advised, multi-manager)

- Regulatory agencies (geographic and structure-based jurisdictions)

The operating model serves as the bedrock for managing the regulatory response; it can be developed as a collaborative effort between senior business leaders, the strategy committee, and the finance team. The operating model should be updated on a regular basis or during specific events such as:

- A merger and acquisition

- The launch of new product

- Geographic expansion

- A corporate restructuring event

Once updated and ready, the model can be a vital tool for the RARE team to use in managing the next stage of the regulatory risk planning and prioritization process: business and product impact analysis.

2. Business and product impact analysis

This step brings in the regulatory perspective for the business: identifying the strategic, operational, and overall impact of regulatory changes/new regulations. The objective of this phase is to specifically highlight areas such as product portfolio, distribution channels, client segments, pricing policies, and geographic presence that would be affected by regulatory changes or impacted by proposed compliance rules, and to arrive at a risk-based resource allocation plan.

So how does the RARE team understand the impact of regulatory changes/proposed regulations on the business? They often use the input from the sensing and influence stage, the operating model, and information from the project management office (PMO) about an initial list of priorities. One tool to typically help with initial prioritization of regulatory events is the risk assessment heat map (see figure 7). While this initial assessment often lacks the complexity for final decision making, it can be useful for prioritizing the work for a deeper risk assessment.

3. Regulatory and financial risk assessment

Once a bird’s eye view of at-risk areas is identified, investment management firms can conduct a thorough risk assessment, using FORREST or a similar framework. Led by the combination of RARE, risk and compliance, and the finance team, the goal of the assessment should be to develop a measurable estimate of regulatory changes’ impact on the business. This forms possibly the most critical step of the entire risk planning process, as the results guide the risk response action plan.

The first step in the risk assessment exercise is often to develop the assessment criteria and determine scale by answering the following questions:

- What would be the impact of the risk on the business?

- How likely is the implementation of the regulation to impact the firm?

- How prepared is the firm in case the regulation comes into effect?

- What is the time it would take for the regulation to impact the firm once it is approved?

- How fast could the firm recover in the event the risk impacts the firm?

- How much idle time can the firm tolerate before responding to the risk?

Assessment criteria should be tailored to suit the requirements of each firm. Once the criteria and scale have been finalized, the risk and compliance team can conduct a detailed risk assessment for any proposed regulation or new compliance requirement. Leading risk assessment practices have evolved from a largely qualitative assessment based on descriptive scales to a more detailed quantitative assessment utilizing data gathered and tracked through the compliance function. Internal and external audit points, regulatory findings, and other legal actions are some of the traditionally qualitative sources that are in transition to structured data that support quantitative analysis. Quantitative risk assessment models can estimate the impact on gross profit margins, cash flows, or earnings over a given time horizon at a given confidence interval, and can also identify compliance-related issues that may have a long-term impact on brand.

Firms may find value from external resources, which can help eliminate any gaps overlooked by the internal team and offer an independent review for the risk assessment scoring process. This structured assessment approach provides a holistic perspective for assessing regulatory risks and their interactions.

4. Explore business model responses

For senior management and business leaders, it’s important that the unique risk profile of their firms remains top of mind when making strategic and business decisions. As a part of this, a large number of investment management firms have adopted risk appetite statements (approved by the board) to guide senior decision makers in formulating business plans and regulatory responses.12

Once the risk prioritization process is completed, the information can serve as a vital part of the organization’s change plan. The RARE team can coordinate with business leaders to highlight all the components of the business, such as the product portfolio, client segments, distribution channels, and geographies most heavily impacted by the regulatory changes. Business leaders can then propose multiple ways in which the operating model can be adjusted to remain compliant under the proposed regulations. For minor tweaks in the operating model, such as product pricing policy and distributor reimbursement, teams can conduct a detailed cost/benefit analysis to understand the impact on the overall business. If a significant change in the operating model is required, such as the divestiture of a product or business unit, business leaders can look at different business modeling techniques to understand the overall impact. In the case of the DOL fiduciary regulation, firm responses varied widely, from spinning off broker/dealer businesses, to acquiring independent broker/dealers, to changing fee levels and structures.

The details of the shortlisted operating model changes and their corresponding impact can then be discussed with the strategy committee (or similar body). This would enable the firm to develop a regulatory response plan that aligns with its strategic roadmap.

5. Develop a regulatory change plan

After exploring and shortlisting different operating model responses, the key objective of this step would be to develop a target operating model that would remain compliant in the face of key planned regulatory changes. This would typically require close coordination with members and teams across functions, especially the RARE, strategy, and risk and compliance teams. Based on the earlier steps executed in this process, a high-level regulatory change plan should be integrated into the operating model, which then would become the target operating model. To complete this step, firms would need to evaluate the three key cornerstones of a successful execution in perhaps a similar manner:

- People. Review whether the company needs to refine the skill sets of current employees or hire new employees with specialized skill sets to implement the plan. More broadly, review whether organizational changes may be needed, such as developing new business units and reporting lines.

- Process. Review existing operational, reporting, monitoring, testing, and documentation processes. Determine what changes may be required and check if automation can provide any benefits.

- Technology. Mobilize a cross-functional team to prioritize technology efforts and develop a technology roadmap that would complement the target business blueprint.

After all of the teams have developed the regulatory response plan and integrated the same into the target business blueprint, the RARE team would handle the communication with the business leaders and board for final approval, summarizing the key findings of the risk assessment stage and highlighting how the current regulatory change plan would meet the proposed regulatory changes with a margin of safety. Once all the queries from the business leaders and board have been heard and addressed, the RARE team would then begin to implement the regulatory change plan.

Implementation

The target operating model would direct the development of compliance programs. The model should enable accountability and integration within the organization to address the changes impacting it.

Now we will address the gaps identified in the three key cornerstones, noted above, to transition from the existing operational model to the target model. We will outline ways in which the organizational structure, business processes, applications, data sources, and repositories may be modified through the transition to meet the target operating model.

These phases highlight the leading practices of many effective compliance programs, where capabilities are formed to address multiple regulatory requirements across business units and processes. But there are many approaches to effectively manage organizational change. These components are fairly generic and apply to many change management paradigms. The goal of this implementation section is to highlight regulatory-specific aspects of organizational change, as opposed to discussing the pros and cons of any particular project management approach.

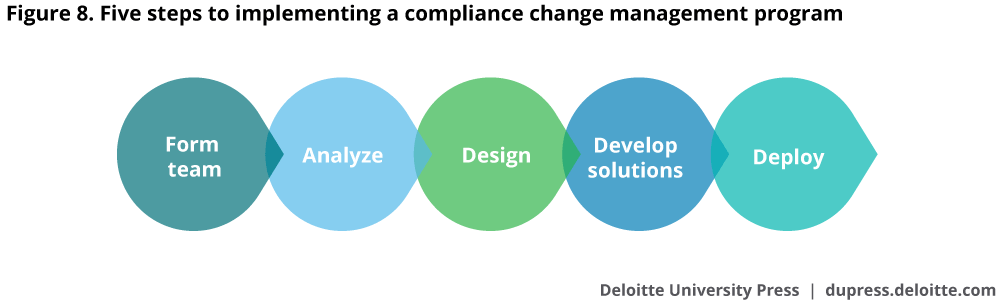

Five steps to implementing a compliance change management program

Form the team

In this stage, the starter pistol goes off as the RARE team typically hands the project over to the Project Management Office (PMO). The PMO often oversees project implementation with efficient staffing; it continues to communicate with the RARE team to understand the new requirements, priorities, and timelines to effectively manage the organizational change. No matter how the project is staffed—dedicated personnel, people drawn from operating lines, or an outsourced team—including or coordinating with the RARE team can mitigate additional uncertainty that may arise.

In this context, the RARE team can be charged with coordinating multiple, related regulatory projects to build institutional knowledge over time about solutions for regulatory outcomes. Having mechanisms in place like this often allows firms to evolve in such a way that eventually, developing solutions for improved regulatory compliance may become part of the corporate culture.

Analyze

The path toward implementing the target operating model can be difficult to follow, with diversions along the way. The analysis phase often has to balance long-term strategic direction with the unwavering compliance deadlines of new regulations. This may mean updating applications slated for retirement, while readying more strategically aligned replacement solutions. One of the unique aspects of regulatory-driven change is that neither the regulations nor their timelines are chosen by the industry. While these dynamics can complicate development, they also highlight the benefits of having regulatory readiness embedded into a firm’s culture.

Rather than address compliance on a per-regulation basis, the regulatory projects portfolio should be looked at as a whole to drive efficiencies, identifying and replicating similar processes that are incorporated into different business units. Take, for example, the Investment Company Reporting Modernization (ICRM) rule, which may require some IM firms to upgrade their systems because the information required by form N-PORT is unlikely to be captured using a single-source system.

If we look at the ICRM and the Liquidity Risk Management (LRM) rules in tandem, the touch points can be noticed. Forms N-PORT and N-CEN came into effect with the issuance of the ICRM rule. Certain sections of these two forms deal with portfolio investment liquidity classifications, use of credit lines, and inter-fund borrowing and lending disclosures. Importantly, these components form part of the LRM rule also,13 providing a small, but clear, example of the benefit of thinking holistically about regulatory change.

Client onboarding provides an example of how viewing a single regulatory issue holistically can benefit an organization. Regulatory improvements in an organization’s client onboarding processes can lead to greater connectivity and coordination among stakeholders. When document management includes tagging and indexing with cross-departmental codes and approvals, a single, authoritative repository with parallel access provides consistency and efficiency.

The analysis phase typically establishes the coordinated path to the target operating model, including the temporary stops along the way that ensure compliance is achieved at all the appropriate deadlines in the most efficient manner possible.

Design

A compliance program’s success is often reflected in its ability to establish a risk-based approach to regulatory compliance by mapping regulations to business units, products, and geographies.14 Firms often face resource allocation decisions that can result in taking “good enough” steps to manage certain risks. The RARE team can help senior management make informed resource-allocation decisions when designing the regulatory compliance capabilities.

The success of the design and perhaps regulatory readiness itself likely depends upon the design team’s understanding of the flow of both the current and target operating models, so this function should be well-staffed with the right people.

Develop

The development phase of a regulatory compliance project is often no different than other projects not driven by regulation: It is all about execution. The development phase should deliver on the design. When the design is good and detailed, the development properly executes tasks that deliver the design, or target operating model. Regulatory-ready firms leverage their existing resources and strategies to achieve their development goals. The culmination of the development phase is quality control, a standard practice in all development projects.

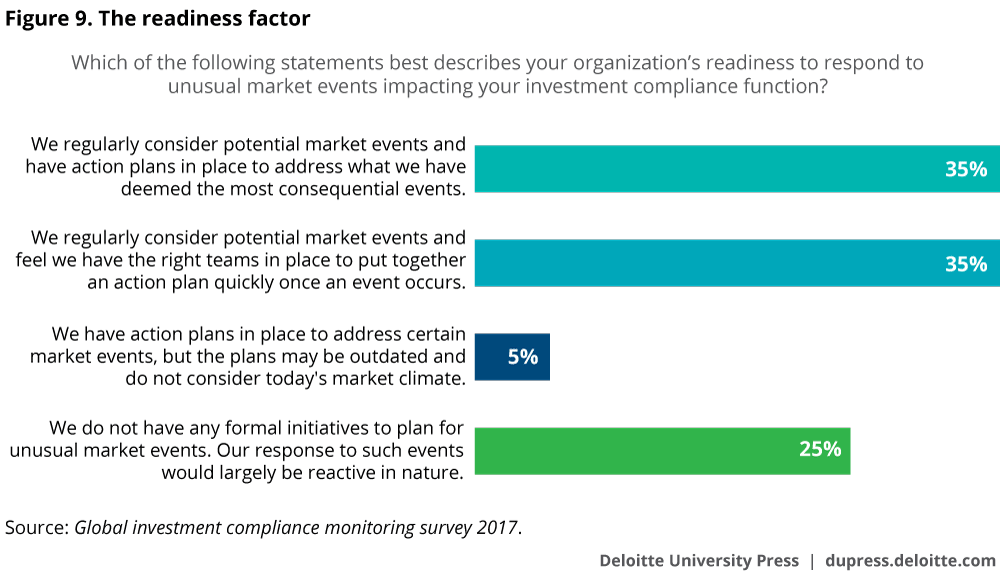

In the regulatory world, however, execution can be tricky. While monitoring and reporting compliance information is a first step, firms can be more proactive in mitigating risk with alerts, and required compliance sign-offs for flagged transactions and activities (see figure 9).

These steps bring efficiency to the operation while maintaining compliance controls. The Global investment compliance monitoring (ICM) survey 2017 by Deloitte revealed that only 35 percent of the participant firms keep tabs on potential market events and have an action plan in place to address the unintended consequences.15 Firms with leading practices often build this functionality into their systems to automatically track market events while also using alerts to signal when thresholds are crossed in internal activities. These leading practices go beyond the development of the new target operating model to also bring efficiencies to the entire organization through well-communicated alerts and thresholds.

Deploy

Regulatory-ready organizations frequently go live with new capabilities and processes. As with development, deployment should follow the standard practices of the organization, with a few notable additions or modifications geared toward regulatory change.

Audit trail and accountability

The regulatory change management solution should include a full audit trail to see who was assigned a task, what they did, what was noted, and what was changed. This would enable the organization to provide full accountability and insight into regulatory review and change, and the ability to demonstrate what actions were recommended or taken.16

Compliance testing

Documenting testing results is often critical; it provides stakeholders with relevant and reliable information about the compliance program. Regulators view this practice as a demonstration of the company’s commitment to ethics and compliance and it instills confidence.17 Secondly, testing can help reinforce the message that the firm has resources devoted to compliance and acts in good faith. Most boards require substantiated information on the effectiveness of the compliance programs in order to execute fiduciary duties. Finally, internal and external counsel could regard the testing results as an indicator of the company’s diligence around ethics and compliance and as part of their legal strategies.18

A great testing program can differentiate itself from a good one by going a step ahead and clearly documenting both vulnerabilities and key controls across each of the three lines of compliance defense. Then these vulnerability and control points can be tested repeatedly using statistically valid sampling methods and using the risk assessment results to identify the business units and business processes where key compliance risks are most likely to present themselves.19

Management reporting

Leading practices in regulatory readiness often demand leading reporting capabilities. The leading practice here is developing a comprehensive compliance dashboard, which should:

- Be tailored to multiple classes of users, assigning responsibilities within each class

- Have drill-down and filtering functionality

- Identify risks, events, patterns, and thresholds that can be linked to responsible parties, controls, and documentation

- Send out compliance alerts within the organization

- House the compliance guidelines and policies for research and to comply with information requests from regulators

As IM firms conduct business in an ever-changing world, the operating model is continuously tested. This often makes it critical for firms to continuously monitor and periodically test its effectiveness. Regulatory readiness implies that firms are managing these risks as they occur, and also adjusting their policies and procedures to address root causes or vulnerabilities.

Progressive approach to compliance

Experience tells us that regulatory compliance is not an event; it is a culture that shapes the way firms continuously conduct their operations. As such, regulatory readiness is not episodic, nor is it based on the latest iteration of organizational change that brings the firm into a favorable regulatory posture with declarations of “mission accomplished” as projects are implemented. Only when risk management and regulatory compliance become part of a firm’s culture can the necessary investments in people, processes, and technologies to achieve a regulatory-ready organization take place. These regulatory-ready organizations manage change as though it is ever-present. With this type of posture, institutional knowledge builds, and the firm can manage the next regulatory change more effectively than the last.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.