A consumer-centered future of health Deloitte’s 2019 global health care consumer survey finds evidence that the future is now

16 minute read

21 November 2019

Our survey finds people are exhibiting traditional “consumer behaviors” when it comes to health care: They are willing to shop for deals, disagree with their doctor, and use technology to track and maintain their health.

The idea that increased consumerism will help change the health care system is not new, nor is it an idea unique to any one region. From North America to Asia to Europe, digital tools and other technologies are helping consumers take more control of their health, according to results of Deloitte’s recent global health care consumer survey.

Learn more

Explore our country blog series of the consumer survey findings

Learn more about the Future of Health

Explore the Health care collection

Subscribe to receive related content from Deloitte Insights

Download the Deloitte Insights and Dow Jones app

Twenty years from now, we expect health care to be more consumer-centric. Consumers will likely have access to their own health data in an easy-to-use format and will use it to make decisions that help them improve or maintain their health.

Last autumn, Deloitte leaders shared their vision for the Future of Health in 2040—envisioning a world in which technology use accelerates, useful and actionable data flows easily, and the use of tools to maintain well-being will be widespread. This vision of well-being extends beyond physical health to include mental, social, emotional, and spiritual health.

Is this vision realistic? Will people start to act like consumers when it comes to health care? And which countries are in the vanguard of this trend?

The Deloitte 2019 global survey of health care consumers, combined with relevant findings from our 2018 US survey of health care consumers, shows meaningful percentages of people who exhibit traditional “consumer behaviors” when it comes to their health (see sidebar, “Inside the Deloitte surveys of US and global consumers”). The countries we incorporated in the 2019 survey include Australia, Canada, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands, Singapore, and the United Kingdom. “Consumer behavior” encompasses several attitudes and actions that align with being informed, acting independently, and evaluating choices. Some aspects of this behavior that we captured in our survey include: being proactive about health and using preventive care, willingness to disagree with a clinician, willingness to change doctors or health plans if unsatisfied with care or customer service, using technology and digital tools to improve/maintain health, willingness to share data if properly incentivized, and using tools/ratings to find the best quality of care and customer service. These are not comprehensive, but, together, capture some of the important concepts.

For example:

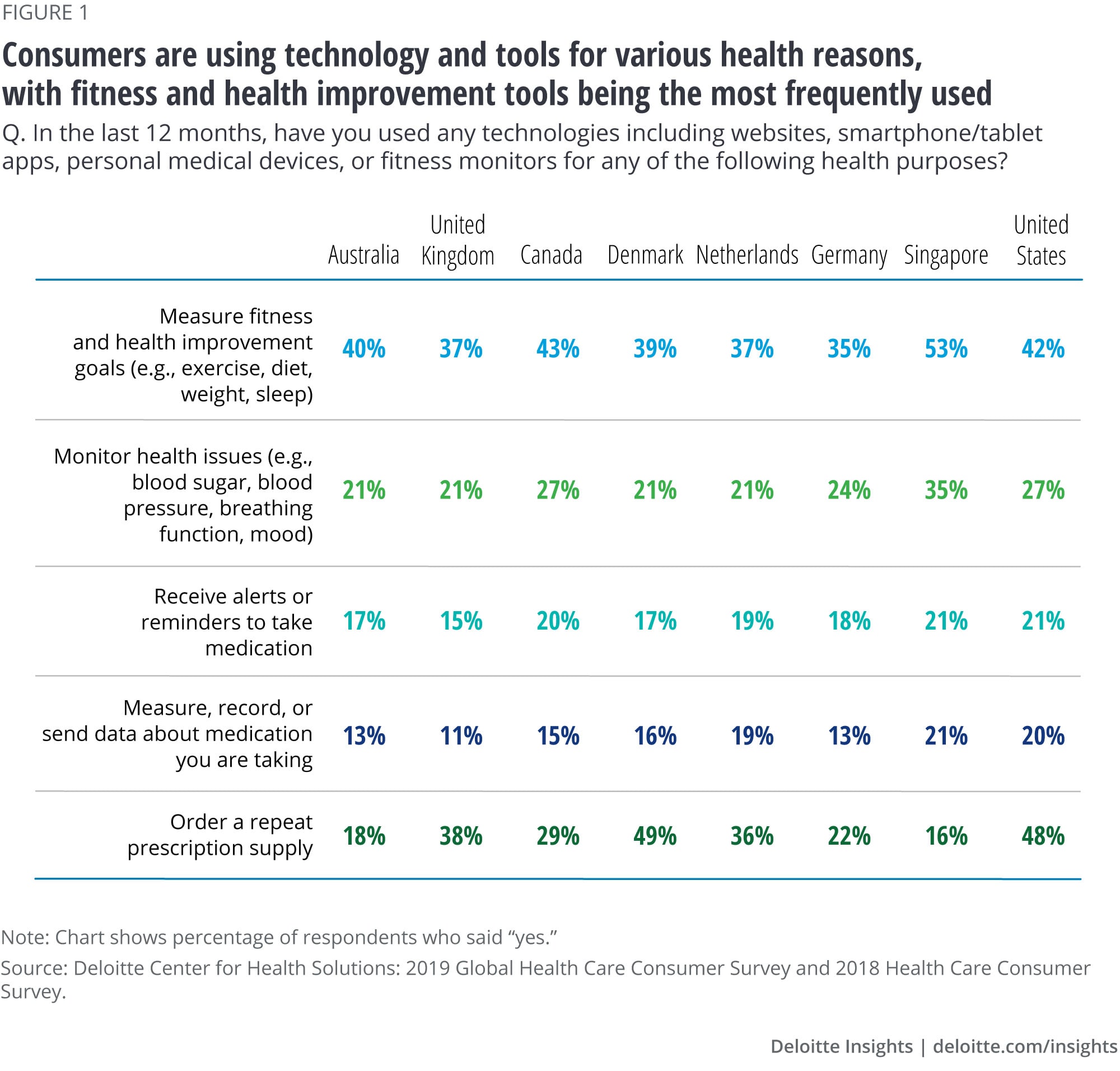

- Increasing use of technology and willingness to share data: A growing number of consumers are using technology for measuring fitness, ordering prescription drug refills, and monitoring their health. More than half of consumers (53 percent) in the United Kingdom—and 35 percent in Germany—measure their fitness levels and set health improvement goals. Many consumers are willing to share their health data in various scenarios.

- Interest in and use of virtual care: Consumers appear to be warming up to the idea of virtual health. More than half of those who have seen a care provider virtually report being satisfied and would likely have another virtual visit.

- High levels of self-efficacy and prevention behaviors: People today seem more willing to tell their doctors when they disagree. This is especially true in the Netherlands and in the United States—where 58 percent of consumers said they were “very likely” or “extremely likely” to do this. In addition, one-third or more of consumers surveyed said they followed a healthy diet, exercised, and followed their doctor’s advice for health screenings and vaccinations (though these percentages varied by country).

- Use of tools to make decisions about prescriptions and care: Consumers are interested in using tools to compare pricing and for user reviews. This tends to be highest in countries where consumers have more exposure to out-of-pocket spending. Nearly half of US consumers and 45 percent of consumers in Singapore are interested in these tools.

- Interest in emerging technologies: Between 20 and 35 percent of people expressed interest in technologies leveraging robotics and artificial intelligence (AI) for health care, preventive care, monitoring, and caregiving.

The percentages do vary by country, reflecting the local health system, availability of various technologies, and attitudes. However, we found that countries were more alike rather than different—though they may be at different levels of maturity in consumerism.

In each of the eight countries where we conducted our survey, we found a meaningful group of people who displayed consumer behaviors regarding health care. Technology is helping us do things faster, less expensively, and more efficiently. Consider how digital tools and technology are changing the restaurant industry. For example, between 2019 and 2022, restaurant delivery is projected to grow at three times the rate of on-premises sales, with the majority going to digital orders. Although this trend does not end the need for physical restaurants, it has pushed the restaurant industry to adapt to new customer preferences.1 We anticipate a similar trend in health care.

How will technology affect stakeholders in the health sector? Today’s industry stakeholders, companies considering entering health care, health financers, and others should make sure that their future strategies incorporate a meaningful emphasis, not just on improving health but also on enhancing the overall consumer experience.

Inside the Deloitte surveys of US and global consumers

Since 2008, the Deloitte Center for Health Solutions (DCHS) has surveyed a nationally representative sample of US adults (18 and older) about their experiences and attitudes related to their health, health insurance, and health care in general. The national sample is representative of the US Census with respect to age, gender, race/ethnicity, income, geography, and insurance source. As part of this effort, in February and March 2018, DCHS conducted an online survey of 4,530 US adults.

In 2019, we expanded our survey to adults (18 and older) in seven additional countries: Australia (n=4,079), Canada (n=4,039), Denmark (n=2,023), Germany (n=3,625), the Netherlands (2,014), the United Kingdom (n=4,165), and Singapore (n=2,014).

Some of the questions asked in our global survey were not asked in the US survey, and we have noted this throughout this paper.

Key findings

Many consumers around the world use technology and otherwise take charge of their health. Even those who are not using technology for health say that they are interested, suggesting that the right tools haven’t been built yet.

Between a third and half of consumers use digital tools to measure their fitness and health, and between 20 and 35 percent of consumers use at-home monitoring devices (figure 1). Consumers in the United States, Denmark, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom are more likely to use technology to refill prescription drugs compared to those in other countries. Our global survey found that Singapore and Canada had the highest percentage of fitness tracker usage—with other countries behind by less than 10 percent. In 2018, 42 percent of US consumers said they used tools to measure fitness and to track health improvement goals, up significantly from just 17 percent in 2013.

Among consumers who use devices to track their fitness data, between 28 and 53 percent said they shared the data with their doctor (data not shown).

More than half (53 percent) of US consumers and between 40 and 42 percent of Canadian, Dutch, Danish, and Singaporean consumers said they shared personal fitness or monitored health data with their doctor. In contrast, just 28 percent of consumers in Germany and the United Kingdom, and a third of Australians shared this information. In most countries, the most common reason consumers said they didn’t share personal fitness data was because they didn’t think their doctor would be interested. Singapore differed, in that the majority said they didn’t have a regular doctor or that they would rather keep this information private.

However, tracking health information doesn’t necessarily result in better outcomes. But health information combined with appropriate interventions, leveraging behavioral economics principles, can lead to healthier behaviors.

Case in point: In 2019, about 600 Deloitte employees (from 40 US states) participated in a 36-week randomized clinical trial to determine if a wearable activity tracker—combined with gamification—would increase physical activity among overweight and obese adults.2 The STEP UP (Social Incentives to Encourage Physical Activity and Understand Predictors) study aimed to understand which data and science-driven approaches are the most effective to engage patients in physical activity (see sidebar, “The STEP UP study”).3

The STEP UP study

The main research question: What is the best way to incorporate social incentives within a behaviorally designed gamification intervention to increase physical activity among overweight and obese adults?

The methodology: The randomized clinical trial included 602 overweight and obese US adults (having a body mass index [BMI] equal to or greater than 25). The participants all wore wearables and tracked their steps. They were divided into four groups:

- Control group: Had no additional intervention beyond tracking steps.

- Support arm: Participants selected a family member/friend who they could email each week and report their progress.

- Collaboration arm: Participants were divided into teams of three people that communicated via email. A team member was randomly selected to represent the team every day. If that team member met his/her goal the previous day, the team kept its points. If the selected member did not meet his or her goal—the team lost points.

- Competition arm: Each week, the three-person teams received an email that ranked all teams by the number of points they had accumulated.

What they found: Those who used gamification had significantly more physical activity than the “control” group or the group that did not use gamification during the 24-week intervention. During the 12-week follow-up, physical activity was lower in all groups, but remained significantly higher among gamification participants than the control group.4

The same strategies that led to increased activity levels in this study might also be used to encourage people to eat healthier or to improve medication adherence. If organizations and health systems can combine the right types of devices and incentives, they could have a positive impact on health.

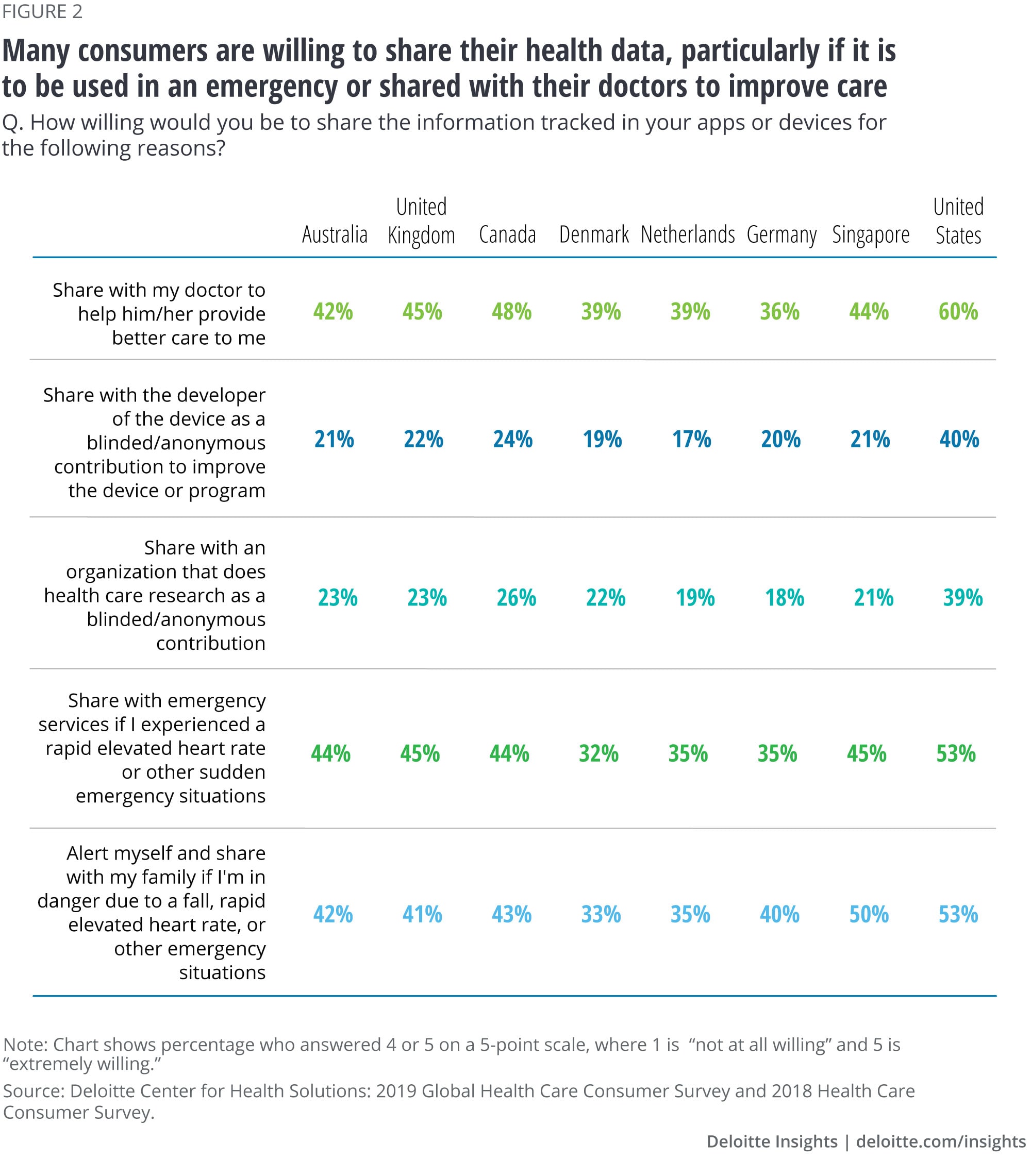

Consumers are most willing to share their tracked health information (in apps and medical devices) with doctors, in emergencies, and with family members.

We asked all respondents to think about future situations where they would be willing to share their tracked health data (in apps and medical devices), regardless of whether they currently track their health data (figure 2).

The results show that:

- One-third to half of consumers are willing to share their health data in emergency situations (either to alert family members or emergency responders).

- Approximately 20 percent of consumers across the US and global surveys would be willing to share their deidentified (blinded) health data with organizations that do health care research—ranging from 18 percent of Germans to 26 percent of Canadians. In the United States, 39 percent were willing.

- Approximately 20 percent (ranging from 17 percent in the Netherlands to 24 percent in Canada) of global consumers said they would be willing to share their personal health data from a medical device with a device developer. The percentage was higher in the United States, with 40 percent willing to share information with device developers.

- Across the board, chronically ill consumers are more willing than healthy consumers to share their tracked health information (data not shown).

People’s willingness to share data is important for developing the interoperable data platforms necessary to drive innovation/discovery. In addition, this data-sharing can help clinicians and consumers become more proactive in the patient’s health management. Health systems and clinicians who decide to work with tracked data will need to determine how to organize it so it’s interoperable. In clinical trials, as another example, organizations/researchers should ensure they have the right patient education, consent, and support systems in place.

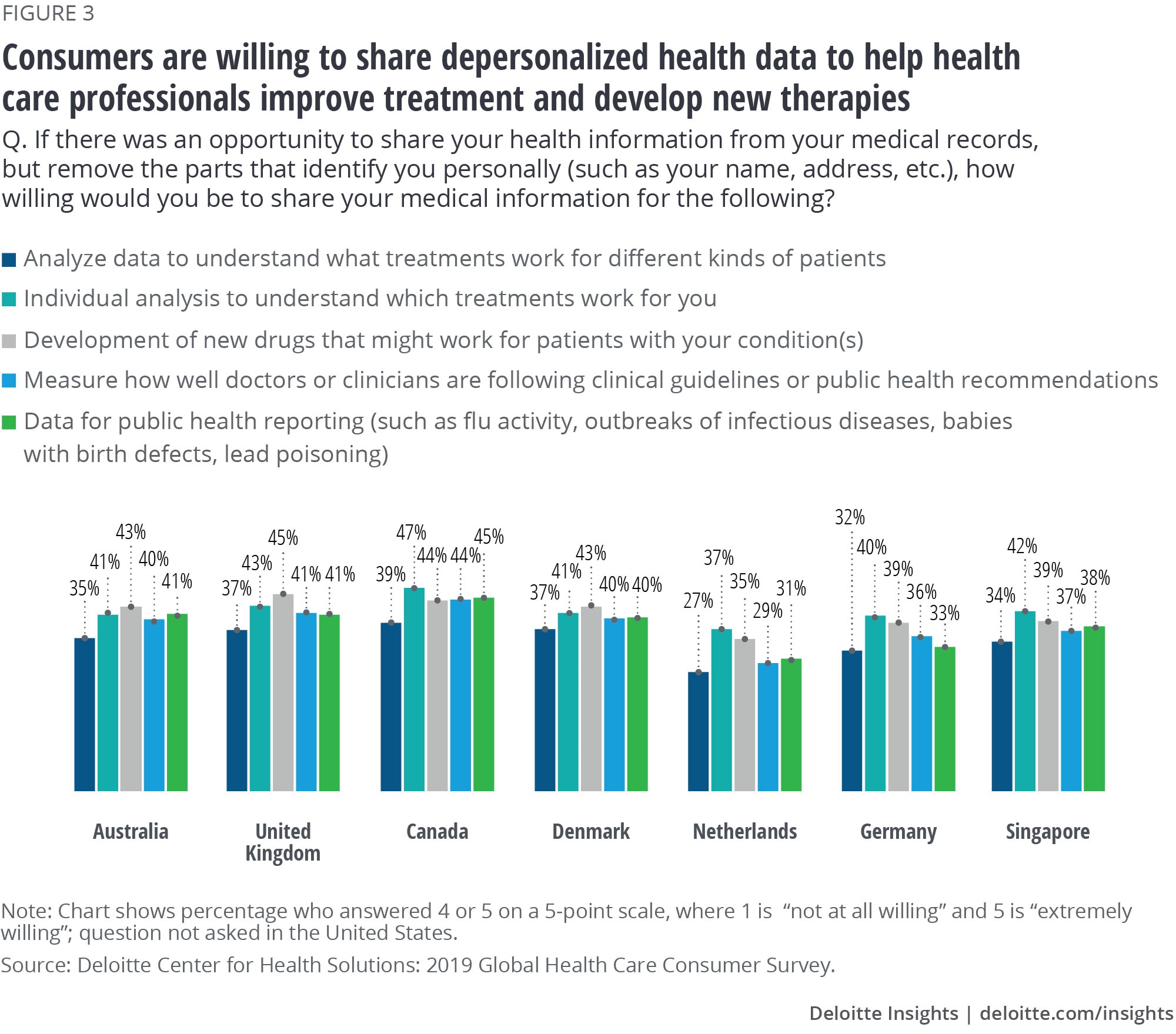

Consumers are most willing to share deidentified information from their medical record for personal analysis and for the development of therapies to treat patients who have the same condition.

Every time a patient interacts with a hospital/health system, another piece of health data is created and stored in an electronic health/medical record. According to our global survey, if this data is depersonalized, consumers are more willing to share their data—in particular, for personal analysis and for the development of therapies to treat patients who have the same condition (figure 3).

In the US survey, we asked a similar question but with different response options. Despite the differences in the question, the findings were similar: Many consumers are willing to share electronic health record (EHR) data with a health insurance plan or a university-affiliated hospital if their personally identifiable information is protected (46 percent each). Fewer consumers said they were willing to share this information with medical device manufacturers (35 percent), state/public health agencies (34 percent), or pharmaceutical companies (31 percent).

How can organizations make consumers feel more comfortable about sharing their data?

Organizations should build trust to make consumers feel comfortable sharing their personal health data. One way to do so is to let consumers own their data. Today, data resides in multiple medical records across different providers and various tracking devices. This makes a complete picture of people’s health unavailable to doctors, researchers, and individuals. It can lead to redundancy in care, missed connections and insights, and a lack of coordination, and makes it difficult for consumers to get appropriate care when they need it most.

Some organizations are working to help pull together data from electronic records and make it available to consumers. For example, in the United States, Apple recently released a feature on their smartphones that can store an individual’s collated medical records.5 Apple worked with the health care community to take a consumer-friendly approach, creating health records based on Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources (FHIR), a standard for transferring electronic medical records. In addition, in England, the National Health Service (NHS) is offering a new app that allows patients access to their own health data from their primary (GP) records and lets them set data-sharing preferences.6 Another app/service in the United Kingdom, Patients Know Best, allows patients to own their own health data (medical records and connected devices) and decide what data to share and with whom to share it.7

These organizations, governments, and developers are working together to give consumers one-stop access to their medical information and control over how data is shared. But this will require interoperability between the various organizations that currently own or store the data. This development could help move the industry closer to centralized records and interoperability.

More consumers are using virtual visits/consultations.

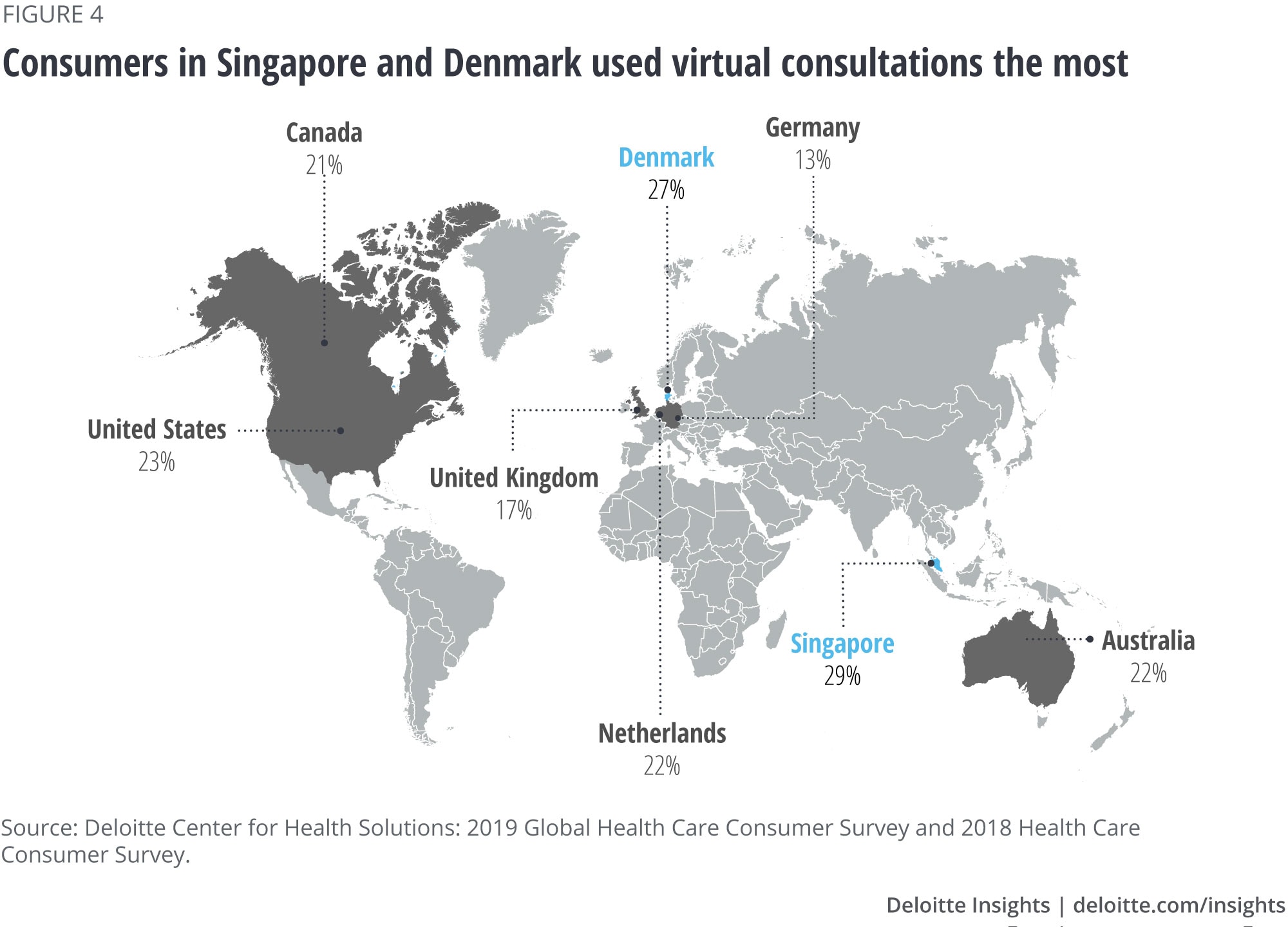

Between 13 and 29 percent of consumers in the seven countries we surveyed have had a virtual visit/consultation with a care provider (figure 4). Consumers in Denmark and Singapore have more virtual visits than other countries surveyed. Consumers in Germany were least likely to have a virtual visit.

One reason for the variance could be related to when virtual visits became available in each country, how the visits are reimbursed, and privacy concerns. For example, Denmark has very strict legislation on data privacy, and access to the doctors’ system is protected by a government-approved security system. This may be the reason why more Danish consumers feel confident using virtual visits. On the other hand, Germany may have lower virtual visits because the country just introduced a national strategy for reimbursements for virtual visits; prior to this legislation, virtual visit use was low (13 percent). However, we anticipate virtual visits to take off, now that clinicians will be reimbursed for their time on virtual visits. In addition, we anticipate higher pickup in the United Kingdom because of the “National Health Service Long Term Plan,” where, starting in 2021, every patient in England will have access to online and video consultations—if they choose.8 However, it’s important to note that having access is one step, but consumers wanting to make use of the option is another.

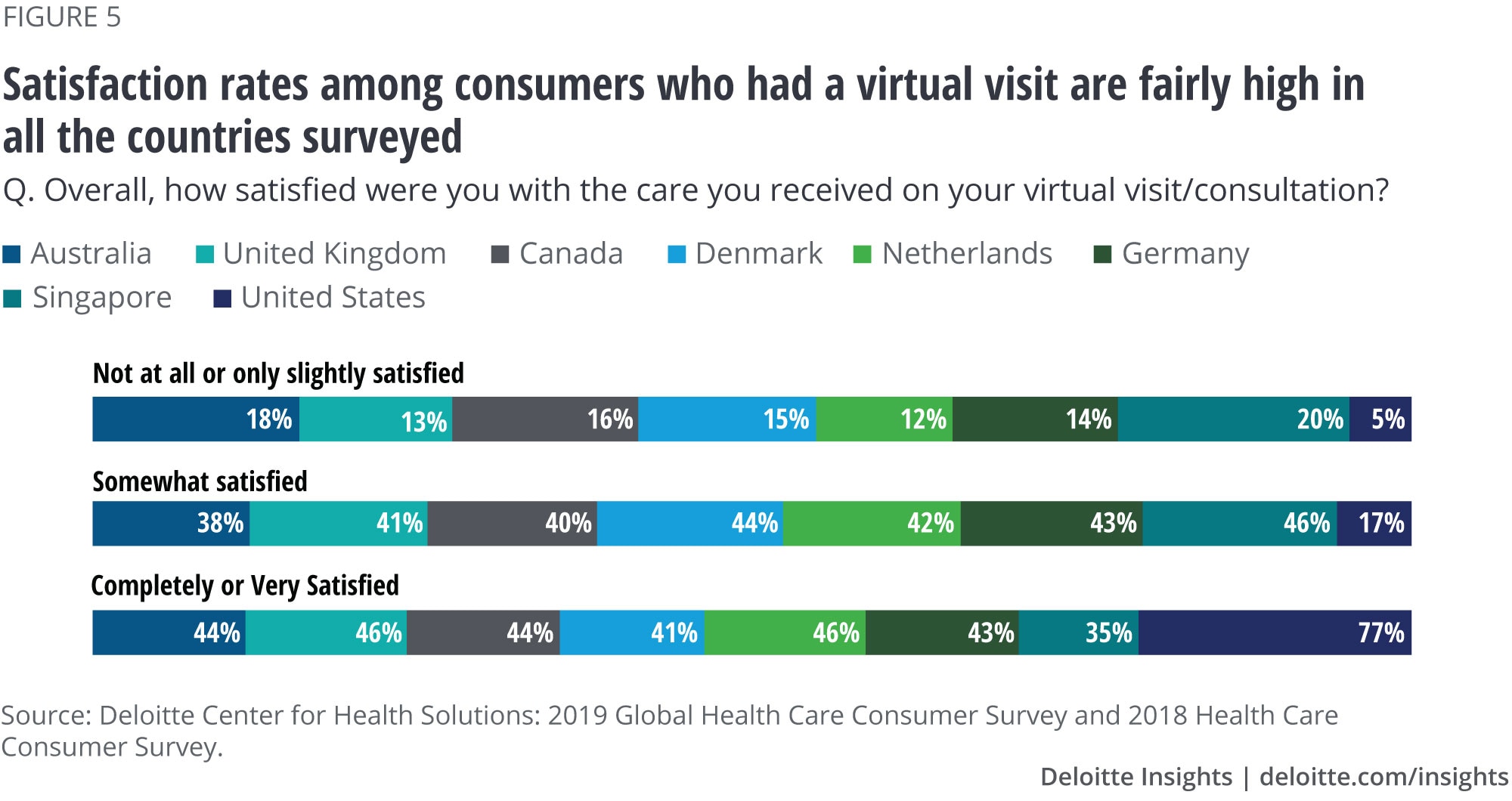

In each of the countries we tracked, we found fairly high satisfaction rates among people who have used virtual visits (figure 5). In most countries, “completely/very satisfied” levels hovered between 35 and 46 percent. In the United States, the percentage was higher—at 77 percent—which may reflect the fact that it has offered virtual visits for longer than most of the other surveyed countries. Most countries’ (Australia, Canada, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom) respondents were similar, with between 41 (Denmark) and 46 percent (Netherlands) “completely/very satisfied”. Interestingly, Singapore had the highest use of virtual visits; however, the country had the lowest rate of people that said they were “completely/very satisfied” with their visit (35 percent).

Between 62 and 75 percent of people who had a virtual visit said they would consider doing it again. The most common reasons people would not consider another virtual visit (across all countries) were:

- I did not feel the quality of care was as good as an in-person visit with my own doctor/clinician.

- I was not able to connect with the clinician the same way I would in person.

- I had to go to another health care clinician in person after the virtual visit anyway.

These findings suggest areas for hospitals and physician practices offering virtual visits to work on improving. One area we found is in training clinicians to conduct high-quality virtual visits. As more physician-patient interactions happen virtually, physicians and health systems might need to determine how to ensure an appropriate web-side manner. This could include how to focus on the patient during the virtual visit, conveying empathy and compassion, and communicating with the patient even while not making eye contact and glancing at data or notes.9

Consumers are no longer passive participants in the health system. They demand transparency, convenience, and access. They are also willing to disagree with their doctors and are more likely to engage in preventive behaviors than in the past.

By 2040, we expect health to be defined holistically as an overall state of well-being encompassing mental, social, emotional, physical, and spiritual health. Not only will consumers likely have access to detailed information about their own health, they will own their health data and play a central role in making decisions about their health and well-being.

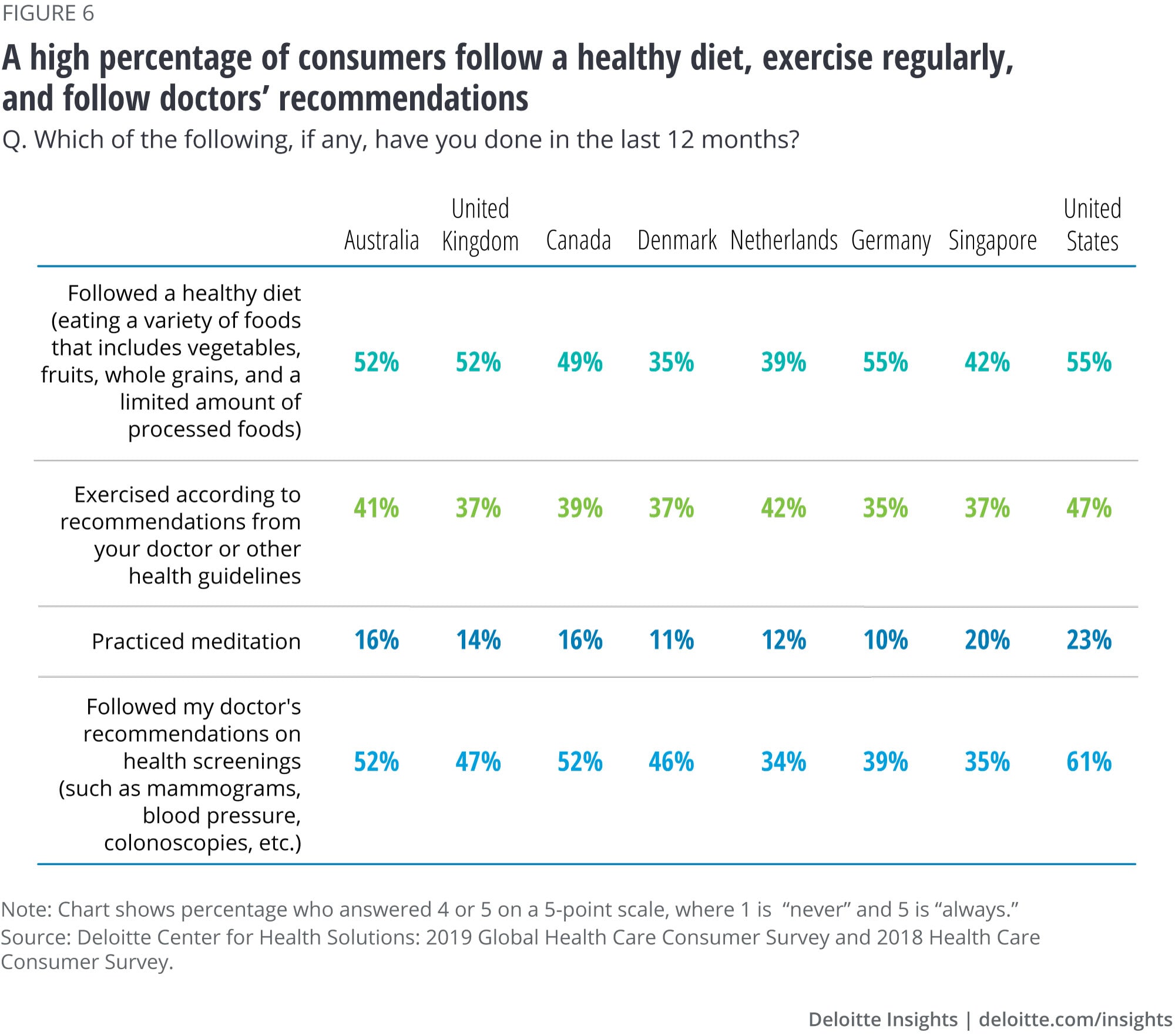

Our survey findings support this vision. A high percentage of consumers said they follow a healthy diet, exercise regularly, and follow their doctor’s recommendations on prevention (figure 6).

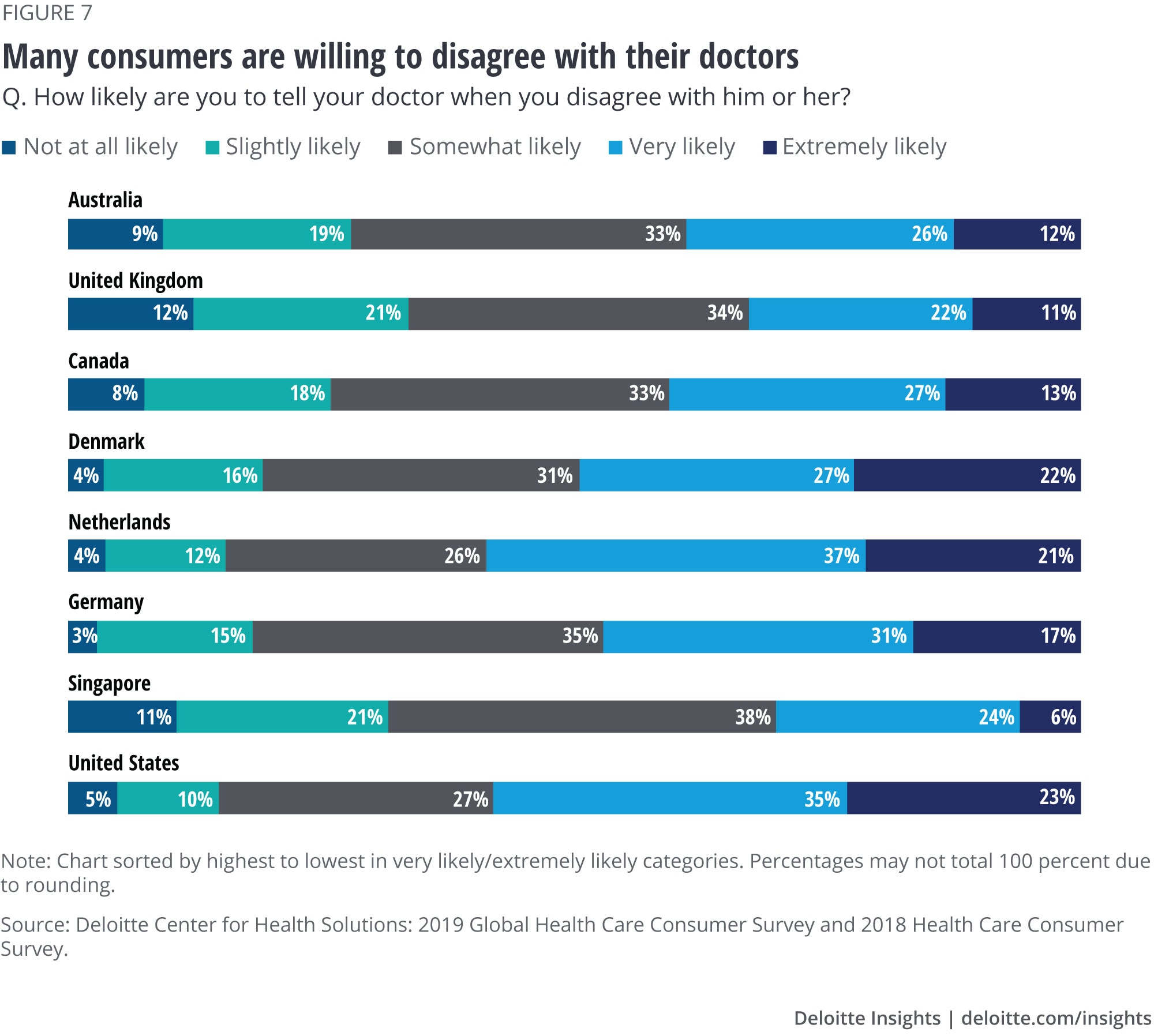

We also found that many consumers are willing to disagree with their doctors (figure 7)—this appears to be most common among consumers in the Netherlands, the United States, and Denmark—and least common in Singapore and the United Kingdom.

Consumers have access to (and use) tools to compare quality and pricing for health care and services.

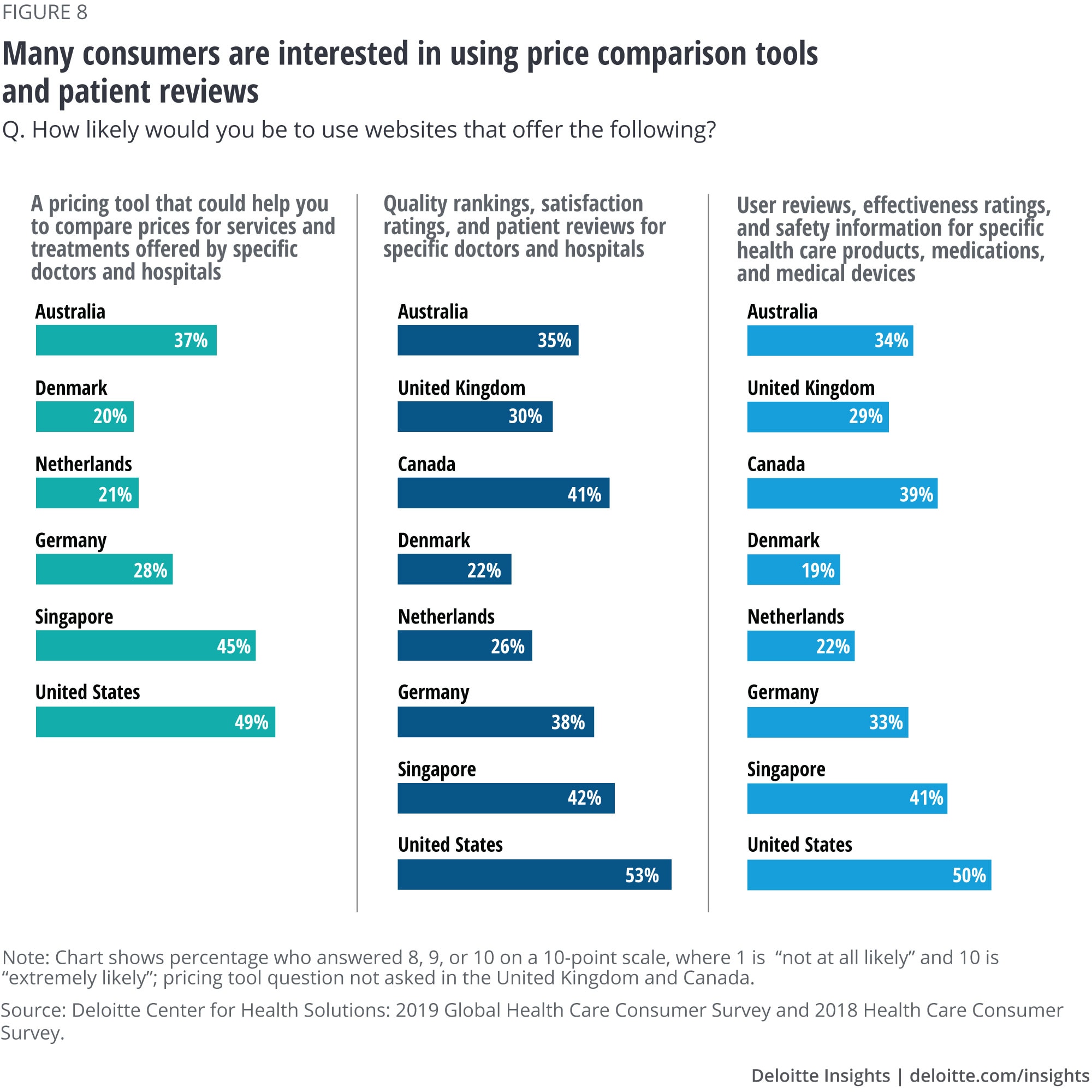

Many consumers are interested in using tools to compare pricing and read user reviews (figure 8). The level of interest tends to be highest when consumers have more exposure to out-of-pocket spending. Nearly half (49 percent) of US consumers and 45 percent of those in Singapore said they are interested in using such tools. In addition, consumers in the United States, Canada, and Singapore were more likely than consumers in other countries to use websites to:

- Look up quality and satisfaction ratings for doctors and hospitals

- Look up user reviews, safety information, and effectiveness ratings

From our US consumer study, we know that consumers’ use of these pricing and quality tools is increasing. For example, the percentage of consumers who look up cost information for health services has nearly doubled over the last three years from 14 percent to 27 percent. As consumers increasingly use these tools, they may be more willing to switch doctors, devices, or hospitals because they have more information on who and what tools provide the best prices and the highest quality.

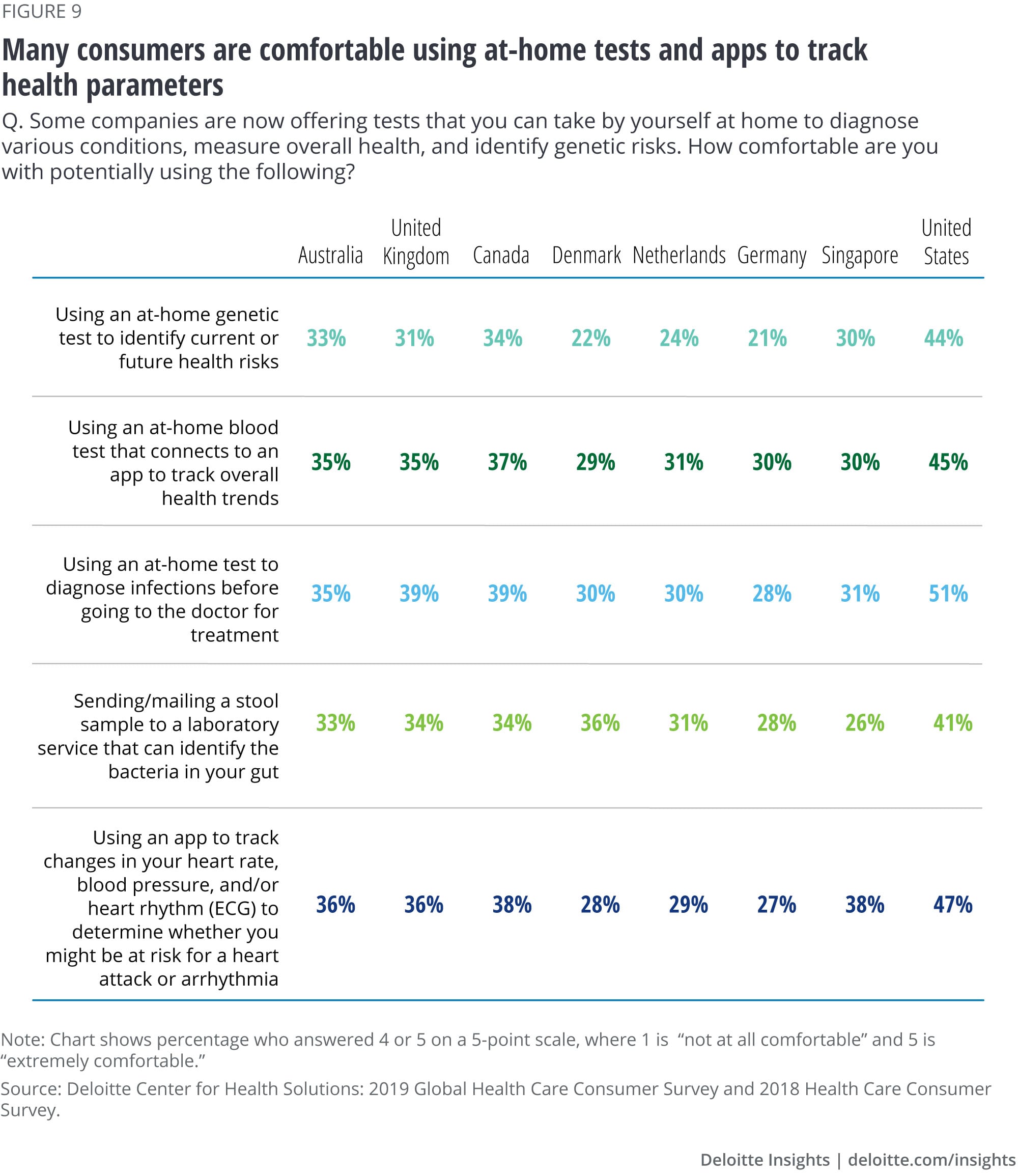

Apps and at-home self-diagnostic and genetic tests are becoming popular among consumers.

At-home tests, mobile devices, and related technologies are enabling new ways to diagnose, monitor, and manage patients and their treatment. Companies are developing these tests and apps along a continuum of wellness and prevention strategies—ranging from acute diagnosis and chronic disease management to identifying future risks of illness.

We found that between 20 and 33 percent of consumers are “very” or “extremely interested” in using apps for engaging with virtual assistants and health coaches, and apps that help them identify health issues (data not shown).

Between a third to half of consumers surveyed are comfortable using at-home diagnostics for various reasons (figure 9). Compared with other at-home tests, fewer consumers said they are comfortable with at-home genetic testing, ranging from 22 percent (Denmark) to 44 percent (United States), and microbiome/gut testing via a stool sample, ranging from 26 percent (Singapore) to 41 percent (United States). Consumers in Australia, the United Kingdom, and Canada have similar comfort levels in each of the categories we surveyed.

As these tests become more widespread, consumers will need actionable information, including medical advice from a physician or a genetic counselor. As consumer interest rises, we expect the development of at-home tests for many other diseases and prevention efforts. The use of these tests also has the potential to help with provider efficiency and making sure the patient is getting the right level of care when needed.

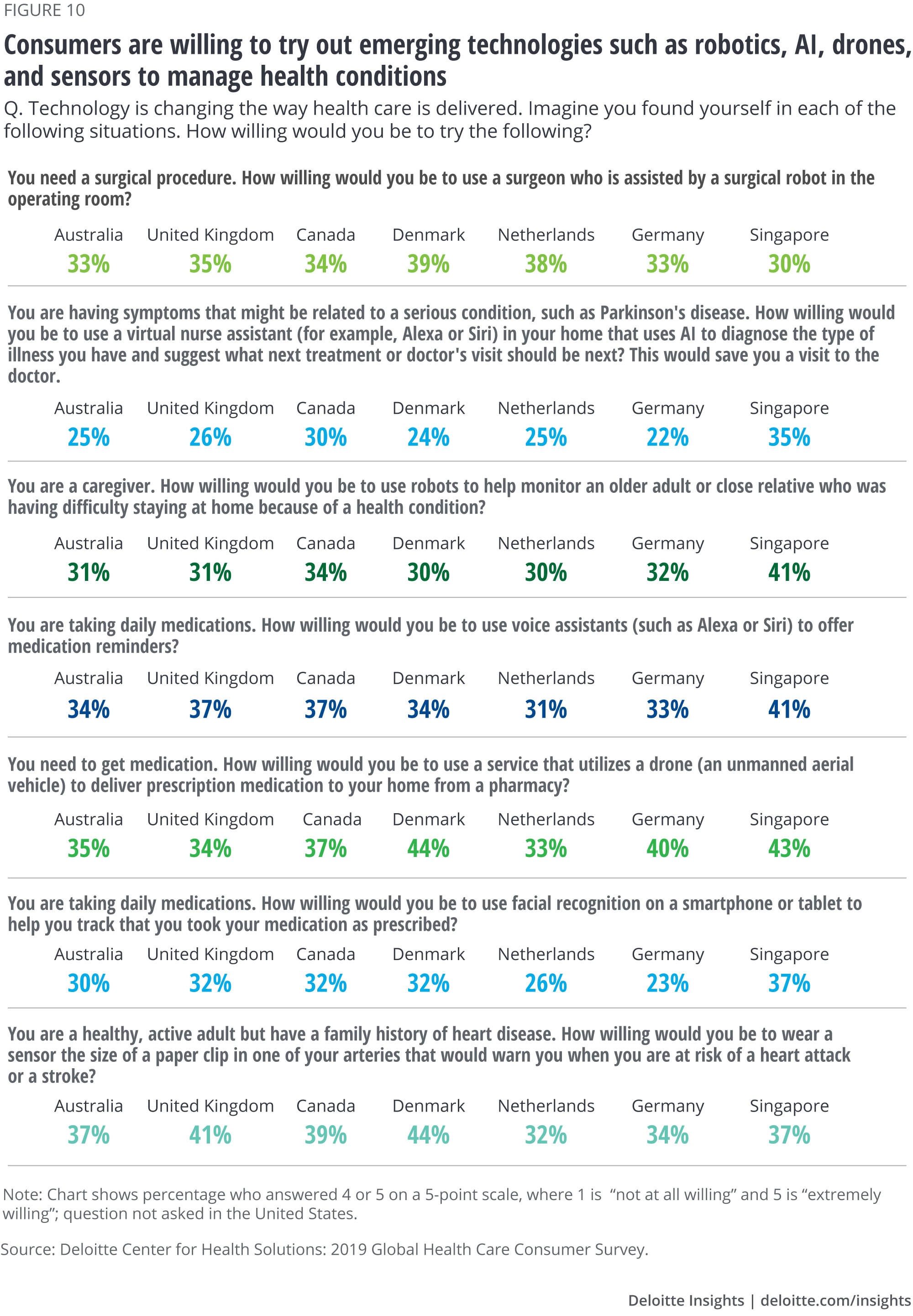

Consumers are open to using emerging technologies.

We found a meaningful number (ranging from 22 to 44 percent) of consumers who are “very” or “extremely” willing to use emerging technologies such as drones, robots, sensors, and virtual assistants (figure 10). And as these technologies advance, we can be reasonably certain consumers will grow more comfortable with these technologies. Digital transformation—enabled by radically interoperable data, AI, and open, secure platforms—is likely to continue to help more and more consumers embrace these technologies.

Conclusion and implications for industry and government stakeholders

By 2040, we expect the consumer to be at the center of the health model. According to our survey results, a meaningful share of consumers are engaging in what we call “consumeristic behavior.”

If one-third of consumers are engaging in 2019, imagine where we might be by 2040?

Stakeholders should prepare now for an increasingly demanding and sophisticated consumer. Engaging the consumer holds profound potential benefits for health care and the future of health. New digital tools can play an important role in the future of care—from monitoring a person’s health to helping individuals get access to more convenient care, to giving caregivers peace of mind and helping older adults remain in their homes rather than move to institutional care. These tools also have the potential to increase consumer satisfaction, improve medication adherence, and help consumers track and monitor their health (including signs and symptoms that may alert them to the need for care).

To meet consumer needs, organizations should provide easy-to-use platforms, high-quality care through these newer channels, and security and privacy of health and personal information.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.

Explore the Future of Health

-

The future of health Collection

-

Radical interoperability Article5 years ago

-

Going beyond compliance to achieve radical interoperability Article5 years ago

-

What will health look like in 2040? Video5 years ago

-

Winning in the future of medtech Article5 years ago