Addressing the social determinants of health for Medicare and Medicaid enrollees Leading strategies for health plans

13 minute read

27 February 2019

Aiming to improve health care outcomes and reduce utilization, health plans are finding new ways to address the social determinants of health among their enrollees. Here are some best practices.

Greater use of the emergency room has been linked to homelessness.1 Diabetes-related hospital admissions have been attributed to food insecurity.2 And social isolation has been identified as a risk factor for stroke and heart attack.3 These are just a few of the ways in which social, economic, and environmental factors—the social determinants of health (SDoH)—have been adversely linked to health outcomes, as well as health care utilization and spending.4

Learn More

Learn more about the hospital of the future

Explore the Health care collection

Read more from the Government and public services collection

Subscribe to receive related content from Deloitte Insights

Health care stakeholders have long recognized these links, and some have been working for many years to address them. Recently, however, health plans, providers, and government agencies have sharpened their focus on addressing SDoH. This is due to several factors. First, there is mounting evidence that some of these initiatives are associated with improved health outcomes and reduced health care utilization.5 Second, some recent state and federal laws now require or encourage plans to coordinate with community and social support providers. (See sidebar, “Recent federal polices are designed to encourage MCOs and MA plans to address social determinants of health for their enrollees.”) And finally, the growth and maturity of value-based care (VBC) provides a financial incentive, if not a financial imperative, to deliver better health outcomes by using resources more efficiently and effectively—a goal that lies at the heart of many SDoH interventions.

While SDoH can impact people from across the economic spectrum, low-income individuals are particularly likely to face challenges related to housing, food, and transportation. Medicaid beneficiaries are low-income by definition, and one-half of all Medicare beneficiaries had incomes below US$26,000 in 2016.6 Both groups are, therefore, key target populations for addressing social needs.

Dual-eligible beneficiaries (“duals”) are also a target population for SDoH interventions. Duals are beneficiaries who qualify for both Medicare and Medicaid, generally through one of the following eligibility criteria: They are low-income seniors; low-income nonelderly individuals with disabilities; or seniors with high medical costs relative to their incomes. These individuals are generally in poorer physical and mental health and have lower incomes than other Medicare beneficiaries. They also account for a disproportionate share of both Medicare and Medicaid spending.7

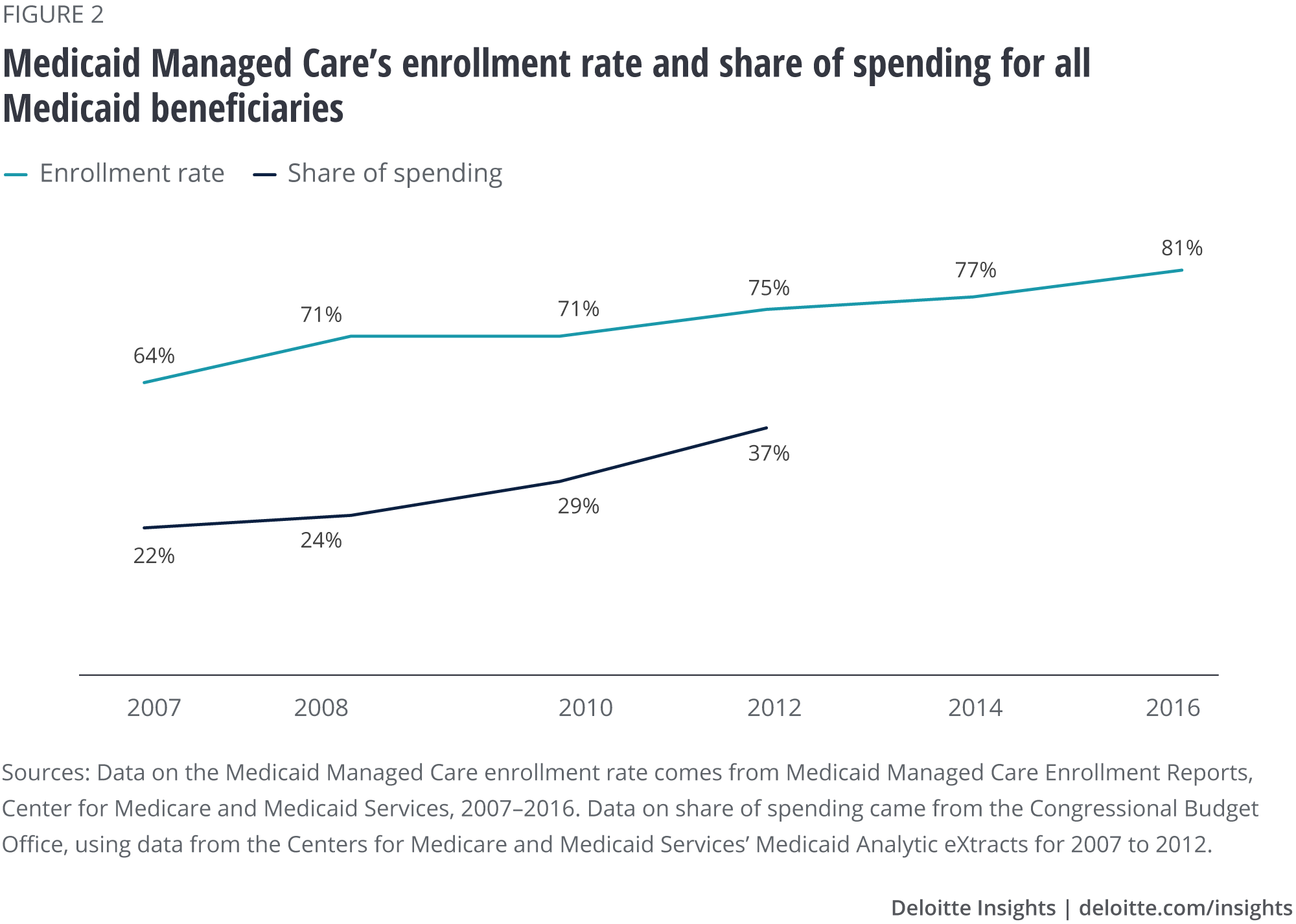

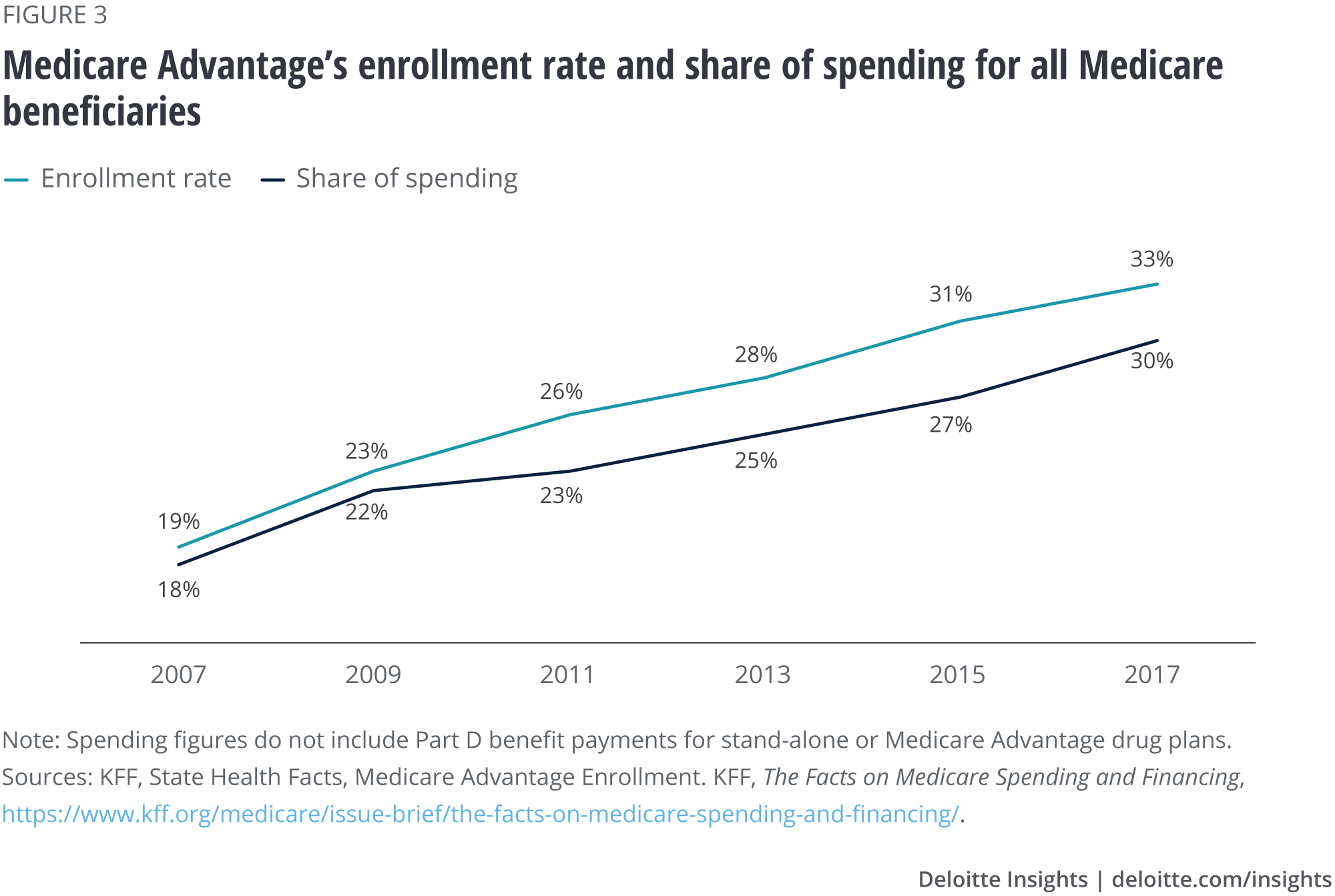

MCOs and MA plans account for a large and growing share of Medicaid and Medicare enrollment and spending (figures 2 and 3). These plans are, thus, critical players within an ecosystem of stakeholders who are focused on addressing SDoH.

To learn what MCOs and MA plans are doing to address social needs among their enrollees, the Deloitte Center for Government Insights and the Deloitte Center for Health Solutions interviewed executives and leaders from 14 MCO and MA plans across the country. We also interviewed leaders from four states to learn how states are directly addressing SDoH, and how they are supporting the SDoH efforts of health plans operating within their states. This project builds upon a previous study by the Deloitte Center for Health Solutions that surveyed a nationally representative sample of hospitals and health systems to learn about their current and future SDoH investments.8

The emerging business case for addressing SDoH

A growing body of evidence shows SDoH interventions can be cost-effective. The current evidence is largely based on pilot programs, small randomized control trials, and population-specific interventions.9 (See sidebar, “Successful SDoH initiatives implemented by health plans.”) Like other forms of preventive care, SDoH interventions that improve health outcomes and normalize health care utilization patterns are considered cost-effective because better health outcomes can be achieved with fewer resources.

The current evidence on overall cost savings/return on investment (ROI) is sparse, but SDoH interventions may pay future dividends. Two of the health plan executives we interviewed told us they define, measure, and evaluate all SDoH initiatives, and that only those demonstrating ROI are maintained from year to year. However, based on our interviews, these health plans appear to be the exception rather than the rule. Most health plan executives interviewed indicated they do not monitor or evaluate SDoH interventions. Of those who do, most say that some interventions are cost-effective, but that overall cost savings have yet to be seen. Initial intervention costs can, in some cases, be significant and are incurred immediately, while the kinds of changes that result in net savings could take years to realize. Nonetheless, most of the executives interviewed plan to continue their SDoH investments because they align with their mission to improve the health of the communities they serve, and because they have faith that the savings derived from better health outcomes and lower health care utilization will eventually exceed the cost of SDoH interventions. As one health plan executive put it, “Addressing SDoH aligns with the head and the heart.”

As one health plan executive put it, “Addressing SDoH aligns with the head and the heart.”

Health plan executives also believe there are other reasons to invest in social needs that make good business sense. Some health plan executives told us that offering SDoH-related services can be a market differentiator, allowing them to win Medicaid Managed Care contracts in some states, attract new enrollees, and establish good will with government agencies, providers, and enrollees. Other executives noted that such interventions can help their plans achieve quality measures that are tied to Medicare and Medicaid bonus payments, such as effectively managing chronic conditions and improving customer satisfaction.

Successful SDoH initiatives implemented by health plans

Philadelphia-based Health Partners Plan (HPP) partnered with a local nonprofit, the Metropolitan Area Neighborhood Nutrition Alliance (MANNA), to deliver “food as medicine” to chronically ill Medicaid and Medicare members who struggle with food-related social needs. Participants of the program receive home-delivered meals tailored to their health conditions and dietary counseling. According to an evaluation, this intervention was highly effective, reducing hospital admissions by 28 percent, emergency room visits by 7 percent, provider visits by 16 percent, and specialist visits by 7 percent. Twenty-six percent of participants with diabetes showed a decrease in their HbA1c levels (average blood sugar levels) while they were in the program, compared to when they began.10

Arizona-based Mercy Care provides permanent supportive housing to Medicaid-eligible individuals with serious mental illness. The total cost of care among 606 participants receiving scattered supportive housing (i.e., individuals select their own housing units in the community) decreased by 24 percent after joining the supportive housing program, from US$20,000 per member per quarter to just over US$15,000 per member per quarter. This reduction was driven by significant reductions in behavioral health costs, including a 20 percent reduction in psychiatric hospitalizations.11

CareSource’s JobConnect program provides enrollees in multiple US states with no-cost services and supports for professional development and employment. According to CareSource executives, data from 2017 showed that, among 392 JobConnect participants, there were measurable differences in health care utilization six months before and after participation in the program. Emergency room visits decreased by 15.5 percent. Pharmacy claims, on the other hand, increased by 37.1 percent, potentially indicating better disease management that may result in lower eventual health care costs.

Leading strategies being used to address social needs

Our interviews revealed four main strategies health plans are using to address social needs among Medicare and Medicaid enrollees (figure 4).

Using multiple modalities to identify social needs

Telephone, online, and mail questionnaires are the most common methods health plans use to screen members for social needs. Plans commonly use health risk assessments (HRAs) and other questionnaires to assess whether a member has social needs. Plans generally administer the questionnaire upon enrollment, annually, and following critical medical or life events. Members who are considered high-risk may be assessed more often. To avoid survey fatigue, HRAs may be short, but may lead to additional assessments and outreach if the initial HRA determines an enrollee to be at-risk for one or more social needs.

In-person and in-home assessments are often considered the most effective screening methods. The health plan leaders we interviewed told us that HRAs and similar screenings generally have low completion rates—often 50 percent or less. However, when administered in-person, those rates can jump to 80 or 90 percent. A member might receive an in-person screening during a clinical encounter like an emergency room visit or because the health plan considers that member to be high-risk based on disease condition or health care use.

In-home assessments are generally reserved for the highest-risk members, such as individuals with disabilities or dual-eligible beneficiaries. Several health plan representatives we spoke with told us that in-home visits can be the most useful method for identifying social needs, especially for high-risk populations. “You go into their homes, you see where they live, and the social determinants become evident,” observed a representative from Tufts Health Plan. An enrollee may be reticent to report issues such as interpersonal violence, but a visit to the home may reveal telltale signs of abuse, such as a sense of fear or anxiety around another member of the household. Home visits can also help establish a trusting relationship with an enrollee, which may alleviate shame and stigma, and allow the enrollee to accept an intervention.

“You go into their homes, you see where they live, and the social determinants become evident.”

Plans also use predictive analytics and machine learning to risk-stratify members and anticipate social needs. Plans combine demographic, geographic, and medical claims data with data derived from social needs assessments to develop predictive models. These models are then used to stratify members into risk categories or assign them risk scores that account for both clinical and social risks to determine the probability of a member having or developing a given social need. Some plans are beginning to use machine learning capabilities to develop these predictive models. Plans may then reach out to high-risk members for case management, referrals to community-based organizations (CBOs), and other assistance.

Some organizations are adding marketing or consumer data to social and clinical data to glean more information via predictive analytics. Third-party information technology (IT) vendors are beginning to mine data not only to anticipate clinical and social risks, but also to identify behavioral risks and attitudes. Consumer data derived from credit card transactions and other consumer research data can include information on spending habits related to food, alcohol, cigarettes, and exercise, as well as an individual’s preferred mode of communication. By combining this data with claims information, electronic health records, and social needs assessments, vendors are working to anticipate whether a member might be at risk for stroke, obesity, or heart disease. By studying media consumption habits, they can tailor outreach via the mediums most preferred and trusted by the individual, including the medium through which the initial health risk assessment is administered.

Recent federal policies are designed to encourage MCOs and MA plans to address social determinants of health for their enrollees

MCOs and MA plans draw from a variety of sources to fund SDoH interventions, including grants, state program funds, the health plan’s own funds, and, if available, Medicare and Medicaid payments. Two policies encourage MCOs and MA plans to provide SDoH-related services to their enrollees.

Medicaid and CHIP Managed Care regulation of 2016

MCOs can choose to cover additional services, above those stipulated in their contracts, that they believe will reduce costs and improve the quality of care through “in-lieu-of” and “value-added” services. In-lieu-of services are services or settings that are not traditionally covered by the state plan or MCO contract, but that the state authorizes the plan to pay for because they are deemed medically appropriate, comparable, and cost-effective alternatives to covered services. For example, a plan may cover home visits for high-risk mothers, infants, and young children as an alternative to a clinical visit to provide preventive health, prenatal support, training in parenting skills, and assistance connecting to other community services. Value-added services can include nutrition classes, peer-support services for individuals with substance use disorder, and home-delivered meals for individuals discharged from the hospital.12

The Medicaid and CHIP Managed Care regulation of 2016 encourages plans to use in-lieu-of services to cover members’ social needs; it clarifies that these services are taken into account when calculating the plan’s capitation rate, unless explicitly prohibited by a statute or regulation. In other words, plans can recoup funds from the state for these services. The rule also broadens the definition of value-added services and specifies that although value-added services cannot be taken into account when calculating the capitation rate, they may be included as a medical rather than administrative cost if such services improve health care quality.13 Counting the service as a medical rather than administrative cost makes covering it more financially attractive and feasible for MCOs.

The CHRONIC Care Act of 2018

Signed into law as part of the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018, the CHRONIC Care Act provides Medicare Advantage plans with increased flexibility to cover additional or supplemental services for a target group of beneficiaries with complex care needs, beginning in January 2020.14 These services may include transportation, minor home modifications to help accommodate walkers or wheelchairs, home-delivered meals that are tailored to specific conditions (such as diabetes or chronic heart failure), and other nonmedical health-related benefits.15

Connecting members to services through one-on-one support

Health plans consider care/case managers and community health workers critical to addressing the social needs of high-risk members. The health plan executives we interviewed told us they refer most enrollees with identified social needs to community-based organizations (CBOs)—local nonprofit organizations that work to meet community needs—and other agencies. However, enrollees who are deemed “high-risk” (often due to diagnosis or high utilization) may be assigned a care/case manager or community health worker, who can work with the enrollee one-on-one to coordinate his or her care. These professionals are critical for helping to assess enrollees; providing a “warm handoff” to CBOs; helping enrollees contact government agencies and enroll in services for which they are eligible; and “closing the loop” on referrals—tracking and recording whether a member received the necessary service.

Peer-to-peer programs can help link enrollees to community resources. Several health plans have set up peer-to-peer programs, in which individuals who have experienced issues such as homelessness and substance use disorder are trained and certified to assist members experiencing similar challenges. Magellan Complete Care of Virginia—which delivers integrated physical and behavioral health care for members in the managed long-term services and supports (MLTSS) program—delivers care through an Integrated Health Neighborhood. This “neighborhood” integrates community resources and nontraditional services into local health systems. As part of this program, certified peer specialists help members connect with services, provide emotional support, and help locate members who may be difficult to find, such as homeless individuals.16

Meanwhile, WellCare has created the CommUnity Assistance Line (CAL), a call line staffed by trained community liaisons. CAL uses peer support specialists hired through workforce development programs such as Ticket to Work and Welfare to Work, as well as military/veteran programs. Peer specialists evaluate a caller’s needs and provide callers with the contact information of relevant community-based programs and services, which have been compiled into a database by the health plan. If the database does not contain a needed program or service, the peer specialist conducts research or works with local, community-based WellCare staff to identify the appropriate program or service, adds the details of the service to the database, and contacts the caller again to give him or her the necessary contact details.17

Plans consider one-on-one programs critical to supporting high-risk members because they allow the member to receive personalized assistance and can help the health plan establish trust with the member through an ongoing professional relationship.

Establishing strong partnerships through formal contracts and VBC arrangements

Multistakeholder partnerships are the core of health plans’ SDoH initiatives. Health plans work closely with city, county, state, and local housing authorities and the department of public health to identify resources, shore up funding, and provide coordinated services to enrollees. Some of the health plan executives we spoke with told us they coordinate efforts with providers to identify and address social needs. Most told us they rely on CBOs to connect enrollees who have identified social needs with services. A health plan might also partner with employers, General Education Development (GED) programs, and landlords to connect enrollees with job and educational opportunities and housing resources.

A formal partnership that aligns incentives can be the key to success. Some plans have established formal contracts with CBOs that define reimbursement arrangements, as well as the responsibilities and expectations for each entity. Such contracts can help strengthen relationships and improve coordination between plans and CBOs, while helping to sustain the financial viability of CBOs.

VBC arrangements are critical to maintaining strong partnerships. Previous Deloitte research shows that hospitals that have adopted a greater number of VBC arrangements—such as participating in accountable care organizations (ACOs) or receiving bundled or capitated payments—report higher investments in social needs initiatives than those with a smaller number of VBC models.

Similarly, several of the health plan representatives we interviewed noted that increased participation in VBC arrangements by network providers has driven the health plans to invest more heavily in SDoH initiatives and to work more closely with providers on such initiatives. Many health plans see it as their responsibility to help providers succeed in their VBC arrangements. One plan told us that part of setting their providers up for success includes sharing data about individuals’ social needs so that health care providers have the information they need to deliver patient-centered care that accounts for an individual’s circumstances. As Fernando Arbelaez, senior director of research, development, and analytics at Gateway Health Plan, put it, “Once you move to a value-based contract, payers and providers are brought together around a common goal: providing more cost-effective care. That means, among other things, addressing the social determinants of health.” Likewise, some MCOs expect providers to screen for social needs following hospital discharge and at other clinical touchpoints, and to relay that information back to the plan. This allows the plan to include that information in the enrollees’ overall risk score and enables the plan to connect the enrollee with needed services.

“Once you move to a value-based contract, payers and providers are brought together around a common goal.”

CBOs may soon enter into VBC arrangements with health plans as well. As part of its value-based payment (VBP) road map, the State of New York is requiring some MCOs to formally contract with and enter into financial arrangements with CBOs and is encouraging CBOs to negotiate bonus payments if health plans realize savings.18 Downside risk arrangements between MCOs and CBOs are uncommon today. However, the same forces that have driven medical providers into downside risk arrangements with health plans—a desire on the part of payers to pay for outcomes, rather than volume—may ultimately compel CBOs to accept upside and downside risk arrangements with health plans, too.

Monitoring and evaluating interventions

Health plans recognize the importance of evaluating social needs interventions; however, few say they can do so today. Several of the plan leaders we interviewed said they have been addressing the social determinants of health for a decade or longer but haven’t been systematically collecting data or monitoring and evaluating interventions. Some say they lack the in-house expertise to run such complex evaluations, which often involve multiple funding sources (some of which are temporary), as well as upstream and downstream financial incentives and costs. Another common reason plans gave for being unable to evaluate interventions was that plans may not know whether a referral or warm handoff to a CBO resulted in a member receiving a needed service. Knowing whether the intervention took place is, of course, a prerequisite to running an evaluation. While several plans told us that some data is shared between the health plan, providers, and CBOs, data-sharing often occurs through manual systems that are resource-intensive and inefficient.

A shared data platform can help plans close the loop on referrals and evaluate the impact of interventions on health outcomes, utilization, and spending. At least one plan told us it is using a multidirectional data platform, which allows it to share data with providers and social services groups using a cloud-based database. Health plan executives noted that this platform allows them to close the loop on referrals and run evaluations that measure the impact of interventions on health outcomes and costs. North Carolina is establishing a statewide resource and referral program to connect health and community-based resource providers, which also will allow them to close the loop on referrals and evaluate interventions.19

Looking ahead

Medicaid MCOs and MA health plans play a critical role in addressing health-related social needs. In addition to the strategies they use to identify and direct resources to enrollees, many plans also invest in the larger community’s social needs by donating to community organizations that address issues such as housing and food insecurity; funding programs and evaluations; and conducting community resource and gap assessments.

Most health plan executives we spoke with told us that when it comes to SDoH interventions, they are still learning. They say that now is the time to experiment with new approaches that can contribute to the SDoH evidence base and hone their business cases.

Some are considering experimenting with technologies such as mobile apps and virtual care, while maintaining one-on-one support programs for high-need and high-risk members. Many are interested in adopting data platforms to share data and evaluate interventions more easily, but say they need to overcome significant technological and operational challenges before they can do so.

As SDoH innovation and maturity continues, health care stakeholders should continue to coordinate efforts, keep abreast of new evidence and tools to incorporate into programs, and ensure that SDoH efforts remain patient-centered and integrated into patient care.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.

Learn more about health care and government

-

Health care Collection

-

Government & Public Services Collection

-

Social determinants of health and Medicaid payments Article6 years ago

-

Innovation in the Military Health System Article6 years ago

-

Medicaid and digital health Article6 years ago