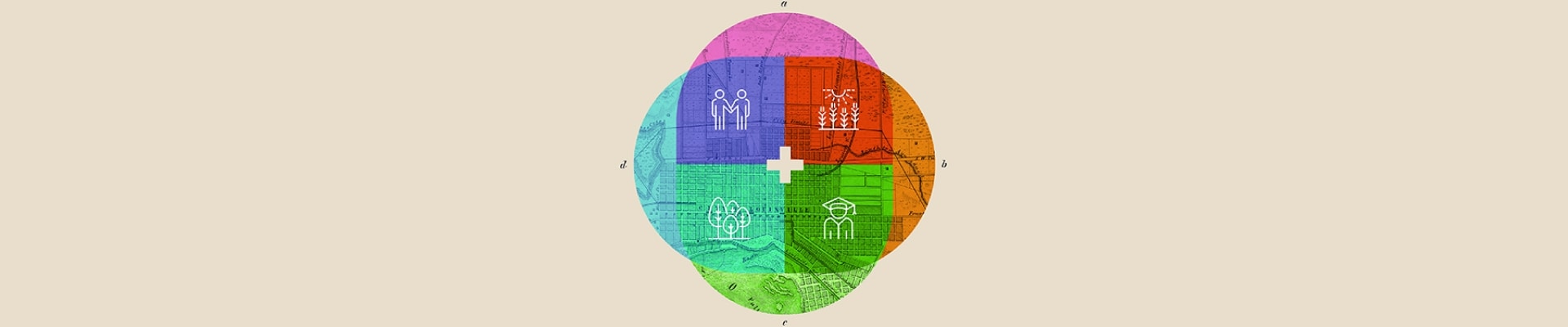

Organization

The organization domain refers to how an employer addresses diversity, equity, and inclusion in the workplace. This is how organizations get their own house in order, to make an impact and demonstrate commitment. Increasingly, as large organizations look at their own workforce, they are identifying real needs and barriers to health. Leading organizations are beginning to act through initiatives such as anti-racism and unconscious bias training programs for employees, including programming that educates people on how to address the health care system’s structure based on an organization’s positioning in that system. Other efforts along these lines include performance incentives based on commitments to diversity, equity and inclusion, and diversity and inclusion hubs to foster innovation through diversity. In addition, some large employers are even looking at screening their own workforce to surface issues such as food insecurity among their people.

Employers should ask themselves questions such as: Is pay equitable, and is it sufficient to support employees’ needs for food, shelter, and transportation? Do BIPOC communities have the opportunities and the support to advance and thrive in the organization? Is there a strong sense of inclusion and belonging across all levels and for all individuals regardless of race, ethnicity, belief system, gender, or sexual identity?

Offerings

Life sciences and health care organizations also should address health equity within their offerings, meaning the products and services they deliver. Though these will differ across providers, health plans, life sciences companies, health technology vendors, and government agencies, there are some common questions that these organizations can ask. These include: Are we making products and services accessible and supportive of all populations’ health? As we design our offerings, are we considering accessibility for all the populations that will use the products and services? Given how integrated data and analytics are to services, are we considering the possibility of bias in artificial intelligence tools and the algorithms they use that may be perpetuating inequities?

For a health care system or health plan, pursuing equity might involve looking at the quality and type of care or services by race, ethnicity, and language to identify and address gaps. More and more health plans and health systems are bridging health and social services to address drivers of health through technology-enabled referral networks with local community organizations. Health systems and health plans can consider questions about pricing, especially what patients and consumers end up having to pay for services. They could also consider other aspects of access, such as whether care is available virtually as well as in person and whether individuals have the ability—enough broadband and technical savvy—to use virtual care.

Government and commercial health plans are starting to think about how to integrate an equity lens into reimbursement through equity-based contracting—looking at value based not just on average population outcomes, but also as a function of equity across subgroups. More broadly, policymakers can continue to explore ways to advance health equity through reimbursement policies and regulatory requirements.

For life sciences companies, diversity in R&D has been top of mind in order to bring equitable therapeutics into the market. Life sciences companies are also beginning to think about the impact of nonmedical drivers of health on their go-to-market strategies, thinking about what communities their products are targeting, and what role they can play in mitigating barriers to access, diagnosis, and treatment. And organizations actively engaged in mergers and acquisitions might think about whether such deals might support or enhance their equity strategy.

Community

The community domain is what an organization can do to improve health and equity in its own community—both geographic and virtual. Is the organization a good neighbor, actively listening to its community, and partnering to drive change? Is the organization thoughtful about where it invests in major capital projects? Are community-oriented philanthropy strategies consistent with the organization’s broader approach to health equity?

Comprehensive and tailored strategies rooted in communities can connect clinical with nonclinical organizations and foster public-private partnerships to take on the challenges of improving wellness in those communities. For example, to address structural flaws and mistrust of the health system, bidirectional targeted education should be deployed to BIPOC communities. Organizations should partner with trusted community leaders to effectively deliver educational messages in a culturally appropriate manner. In particular, data shows that churches are an extremely trusted community member for Black people and could be leveraged to effectively relay educational messages.22

Organizations can also look for opportunities to invest in infrastructure critical for equitable health, ranging from affordable housing to finding ways to mitigate adverse childhood experiences through building more resilient communities. A range of analytic tools are available that can help inform such strategies by identifying the community’s most pressing issues. Moreover, organizations can engage in communitywide education efforts.

Ecosystem

The ecosystem domain refers to what the organization can do with others—similar or even dissimilar businesses, the government (including as an influencer of policy), and private organizations—to advance an agenda for better health and equity. Examples of action in the ecosystem domain may include promoting and collaborating with minority-owned businesses, or building and sharing free operational tools or technology resources to help organizations across industries take more effective action on health equity. Leaders should consider how their political donations do or do not align with a strategy that promotes health equity. Questions to ask include: Where are the natural synergies? Who can we work with to gain insight and capability? Which opportunities have the potential to have the greatest short- and long-term impacts? What could the industry or sector take on as a group? What are we and others willing to do publicly and, on the record, and what is the vision for our legacy?

How to move forward

1. Build health equity into your strategy. Health equity should be part of everything that your organization does. The health equity strategy should not be separate or siloed. Integrating process and outcome metrics that account for health equity into your business objectives and organizational KPIs can accelerate adoption. As you design your strategy, it is important to take into account the current state of your organization’s culture and capabilities. We suggest a strategic road map that focuses on where you want to be in the future and sets a course based on where you are today.

An example from the leading edge: As evidenced by its “total health” approach, insurer Kaiser Permanente is committed to leading the industry in developing and implementing innovative approaches to improve health equity and eliminate disparities in health care quality and access.23

2. Expect active involvement from all your people. Heath equity is everyone’s job—not just that of HR or customer-facing employees. Demand active allyship and anti-racism, and embed equity into all organizational functions to set new industry norms for improving health.

An example from the leading edge: Wake Forest School of Medicine has implemented a new health equity curriculum to help ensure those receiving clinical education and training would understand and bring a health equity perspective into their future work and teams.24

3. Look for opportunities to address drivers of health. Commit to innovatively addressing non-medical drivers of health within your organization, for your consumers, and throughout your communities. Partner, invest, and coordinate to maximize impact.

An example from the leading edge: Through its Bold Goal program, coverage provider Humana works with community partners to cocreate solutions to address health-related social needs, including helping members access healthy food, connect socially, and address housing needs.25

4. Let the numbers be your guide. Harness data and technology to understand where to act, monitor success, and scale health equity efforts. At the same time, make efforts to identify and eradicate bias from AI and technology solutions.

An example from the leading edge: The University of California San Francisco examined its algorithms and data tools to understand how they reflected bias and discrimination, and made changes to support more equitable decisions and action in health care operations. These actions include, for example, proactively reaching out to patients who might be at risk of not appearing for appointments due to transportation risks.26

5. Hold people and organizations responsible. Go on the record with commitments to health equity, be transparent about initiatives, and challenge peers and partners in other sectors to move forward.

An example from the leading edge: Merck partnered with Drexel University to invest in diversifying leadership across the pharmaceutical supply chain, publicizing its support of this topic and encouraging peer organizations to make similar investments in equity.27

6. Measure results. Measurement is the only way we can know if outcomes are improving or worsening. Health care and life sciences organizations, as well as governments and other interested parties, can assess the extent of health inequity by measuring health care disparities, which quantify differences in health outcomes between different groups.

An example from the leading edge: Brigham Health developed dashboards to measure and track differences in health outcomes between groups served at Brigham, and used this data to design strategies to proactively address racial disparities in health care operations.28

As our nation continues to grapple with the far-reaching impacts of racism and bias on health, the time has come for life sciences and health care leaders to take meaningful action. As we look to the future of health, toward a consumer-centered system that promotes health and wellness, we hope to begin to see the basis of competition in the industry shift from providing care to delivering equitable health outcomes. To position themselves for success in this future, leaders should make health equity core to their organization’s strategy and take action to activate health equity within their organizations, their offerings, their communities, and their ecosystems by addressing inequities in both the life sciences and health care industries and in the social, economic, and environmental drivers of health.