Smart health communities and the future of health Five core components industry and government stakeholders can consider in the shift to health and well-being

23 minutes

06 July 2019

Asif Dhar United States

Asif Dhar United States David A Friedman United States

David A Friedman United States Christine Chang United States

Christine Chang United States Melissa Majerol United States

Melissa Majerol United States

Expanded connectivity and the exponential growth of technology are enabling smart health communities, which could offer a modern take on community-based well-being and disease prevention.

Executive summary

Historically, health care was delivered in the community. Physicians made house calls; birth and death happened inside the home. As the modern hospital developed, health care migrated inside its walls. Meanwhile, the concept of health became increasingly medicalized, and separated from people’s daily lives.

A significant body of research shows that about 80 percent of health outcomes are caused by factors unrelated to the medical system. Our eating and exercise habits, socioeconomic status, and where we live have a greater impact on health outcomes than health care.1

The pendulum is now swinging back to the community. Nontraditional players, including public, nonprofit, and commercial enterprises are establishing “communities” focused on prevention and well-being. These communities can be geographically based local initiatives, virtual communities with a global presence, or hybrids of the two.

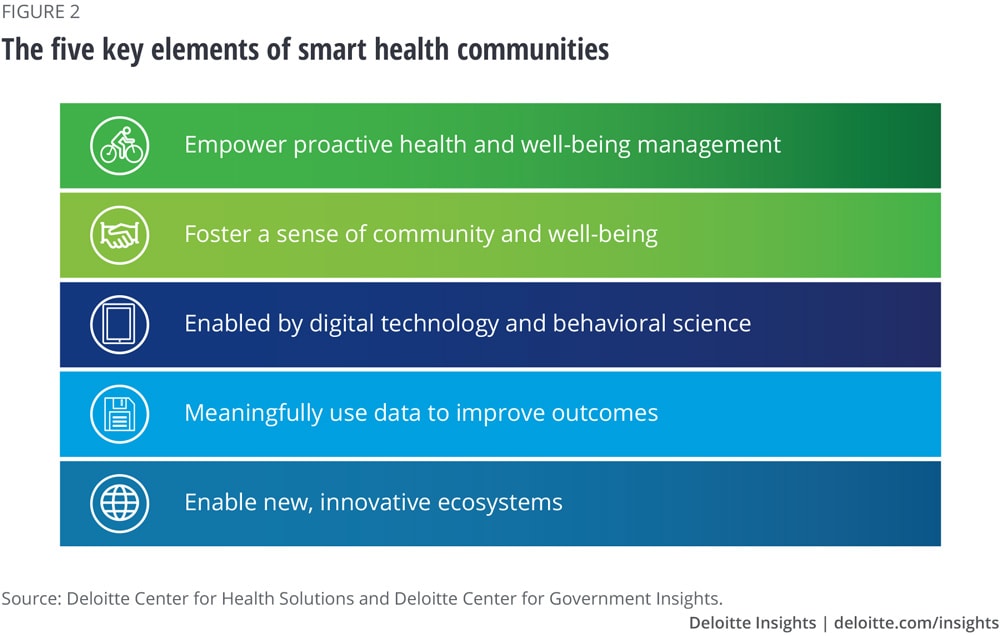

The Deloitte Center for Health Solutions and the Deloitte Center for Government Insights interviewed over a dozen leaders from prevention and well-being initiatives outside of our traditional medical system to learn about the characteristics that are essential to their mission. These interviews have contributed to the development of a concept we call smart health communities (SHCs), which we define as containing some or all the following core features:

- They empower individuals to proactively manage their health and well-being;

- They foster a sense of community and belonging;

- They use digital technology and behavioral science;

- They use data to meaningfully improve outcomes; and

- They create new and innovative ecosystems.

Learn More

Learn more about the Future of Health

Read more from the Health care collection

Explore the Government and public services collection

Subscribe to receive related content from Deloitte Insights

One example of an SHC is the YMCA's decades-old Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP), which uses community to encourage individuals to proactively manage their weight and exercise with a coach in a group setting based at a local YMCA. While successful, these programs have had limited reach since they are tied to brick-and-mortar locations and require individuals to participate in person. Digital technologies have the potential to significantly bring these programs to scale, thus increasing their impact. The widespread use of smartphones—which are prevalent even in lower-income communities—can increase the potential for virtual programs to scale widely. Apps on these phones can incorporate concepts from the behavioral sciences, such as nudges and gamification, to help people stay on track with their health care goals. The recently relaunched WW International (formerly Weight Watchers International), which now uses a technology platform to create a virtual community focused on weight loss and wellness and is informed by the science of behavior change, is an example of an SHC that is leveraging technology effectively.

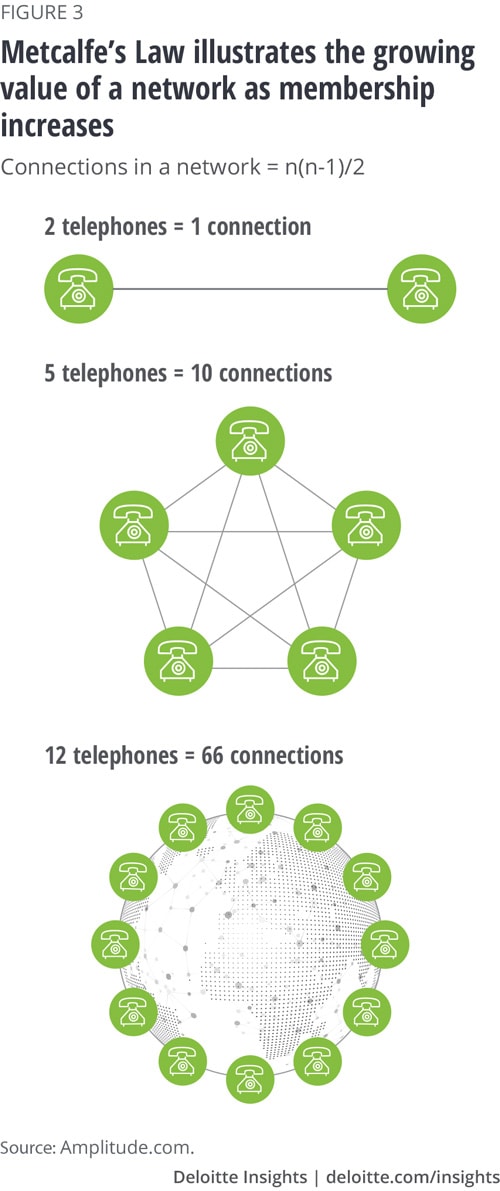

The dramatic changes reshaping health care today are driven in part by the intersection of Metcalfe’s Law and Moore’s Law. Metcalfe’s Law describes how the value of a network escalates dramatically as membership increases. Moore’s Law describes how computing power doubles roughly every two years. In tandem, these two phenomena will likely allow SHCs to grow and become more sophisticated, interconnected, and influential over time. As this happens, the impact of community-based health interventions could be brought to scale, while becoming more personalized. Looking 20 years into the future, technology and other factors may allow more health care to migrate out of institutions and for SHCs to become more integrated into our daily lives, allowing for more preventive and personalized health interventions that can exist alongside—and perhaps even in collaboration with—our existing health care structures.

From sickness to health

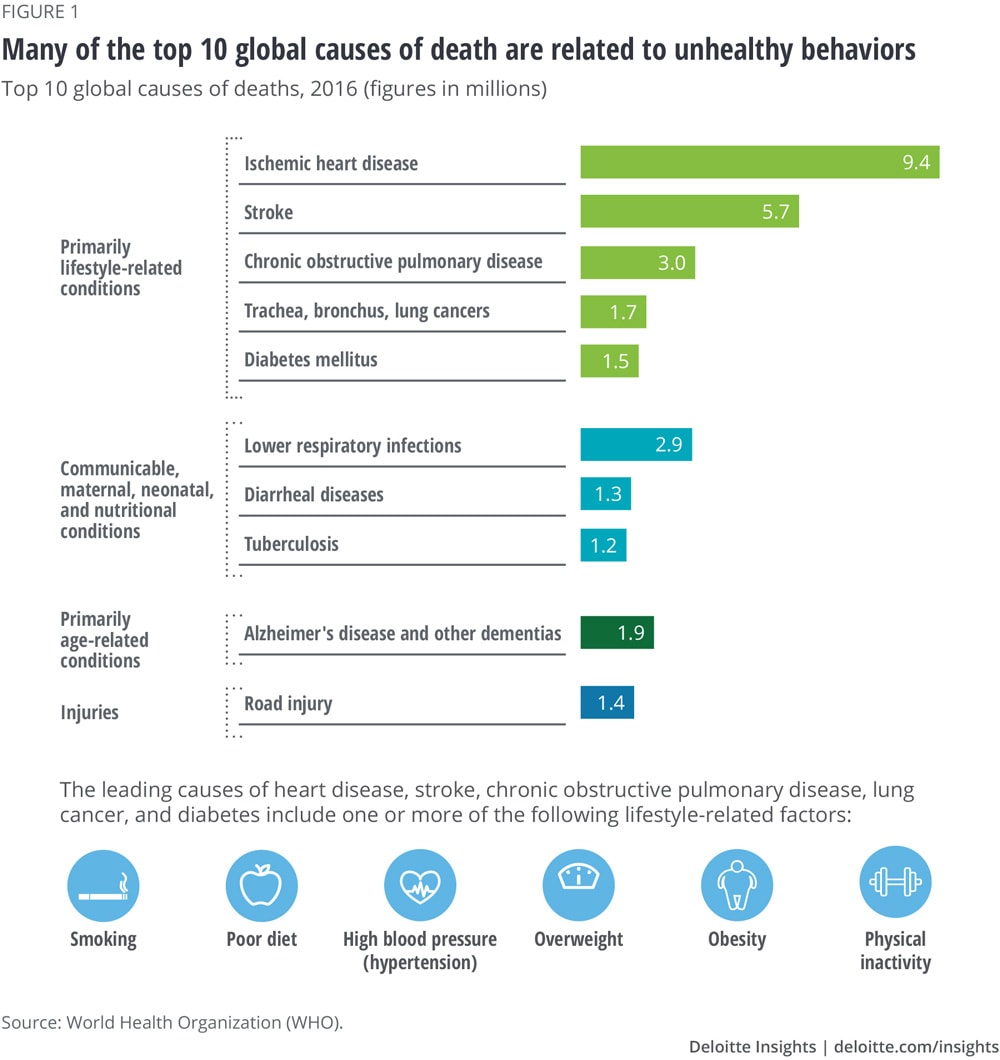

After decades of focusing largely on the health care system as a means to improve health, we now understand that factors outside of it, including social determinants (such as access to transportation, stable housing, and sufficient and nutritious food) and health behaviors (such as smoking, diet, and exercise), generally have a far greater impact on health outcomes.2 Globally, five of the 10 leading causes of death are due to conditions related to unhealthy behaviors (see figure 1).

So, what impacts a person’s health behavior? It’s a complex question, but part of the answer may lie with communities. Our networks—in-person and online—can influence our physical activity,3 eating habits,4 obesity rates,5 anxiety levels, and overall happiness.6 Meanwhile, the characteristics of our communities, including the prevalence of fast food establishments,7 neighborhood walkability indexes,8 air pollution, and other neighborhood stressors9 affect the physical, mental, and cognitive health of community members.

We traditionally think of communities as in-person and place-based (geographic), but the near-ubiquitous adoption of the internet and mobile technology across the income spectrum10 has led individuals to participate in massive and powerful virtual communities. These communities include online message boards and social media networks.

With the understanding that behavior change is critical to disease prevention and that communities have a powerful influence on health behavior, many nontraditional players, including public, nonprofit, and commercial enterprises, are establishing “communities” focused on prevention and well-being. These communities can be geographically based local initiatives, virtual communities with a global presence, or hybrids of the two.

To learn more about these communities and the characteristics that are central to their mission, the Deloitte Center for Health Solutions and the Deloitte Center for Government Insights interviewed over a dozen leaders from prevention and well-being initiatives that operate largely outside of our traditional health care system. These interviews contributed to the development of the smart health communities concept.

What is a smart health community (SHC)?

A smart health community is an entity that operates largely outside of the traditional health care system11 and encourages disease prevention and overall well-being in a geographic or virtual community setting. The basics of SHCs have been around for many years but have evolved because of technological advances and a greater understanding of health behavior change derived from the behavioral sciences. Advanced SHCs have all of the elements shown in figure 2.

The YMCA's DPP, which uses community to encourage individuals to proactively manage their weight and exercise with a coach in a group setting based at a local YMCA, is an example of a geographic SHC. WW International is an example of a virtual SHC, as it uses a technology platform to create a virtual community focused on weight loss and wellness, while encouraging healthy behavior with tools from the behavioral sciences. Many other SHCs also incorporate elements from the science of behavior change—be it a well-timed text message, an individually tailored nudge, or a new way of framing a choice or a problem—to help individuals make decisions to improve their health.

The dramatic changes reshaping health care today are driven in part by the intersection of Metcalfe’s Law and Moore’s Law. Metcalfe’s Law describes how the value of a network escalates dramatically as membership increases (see figure 3). Moore’s Law observes how computing power has doubled every two years or so for several decades and projects similar trends into the future (see figure 4). In tandem, these two phenomena will likely allow SHCs to grow and become more sophisticated, interconnected, and influential over time. As this happens, the impact of community-based health interventions could be brought to scale, while becoming more personalized. Data collected from (and voluntarily shared by) community members, including genetic and medical data, could help detect and prevent disease progression at an individual level, and assist in disease surveillance for the benefit of population health. Looking 20 years into the future, SHCs may become more integrated into our daily lives, allowing for more preventive and personalized health interventions that can exist alongside—and perhaps even in collaboration with—our existing health care structures.

The five core features of an SHC

Empower proactive health and well-being management

SHCs are not just about improving health and well-being—though that is something many are beginning to achieve (see Appendix). They also empower individuals to proactively engage in and demand a lifestyle that promotes health and well-being so that they can take control of their health. SHCs that are tackling health issues “upstream” (i.e., the root causes of disease, rather than the disease itself) include the BUILD Health Challenge communities. BUILD, which stands for bold, upstream, integrated, local, and data-driven, awards funding to sites that address the root causes of chronic disease among their other activities. The National DPP is a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)–recognized lifestyle change program. The program has had proven success in the prevention or delay of type 2 diabetes through evidence-based lifestyle programs that empower individuals to lose weight by educating them about nutrition and physical activity and allowing them to establish their own goals. Programs like the National DPP, Program for Reversing Health Disease (the first lifestyle-based intensive cardiac rehabilitation program reimbursed by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services [CMS]), and the Fresh Food Farmacy, which provides healthy foods to diabetic patients who have trouble accessing them, aim to teach individuals about food so that they have the tools to improve their lifestyles.12

Foster a sense of community and belonging

As their name suggests, the community aspect is vital to SHCs and their success. In addition to the impact of communities on health behavior, individuals also appear to reap larger benefits from activities done in groups rather than alone. One study, for example, showed that medical students engaged in group fitness achieved significant improvements in physical, emotional, and mental health, while those who exercised alone did so for twice as long and achieved improvements in mental health alone.13 One reason for this may be that communities can accentuate certain social dynamics in ways that can improve health outcomes. For individuals who enjoy competition, sharing goals and outcomes data with peers can provide motivation to continue with diet and exercise regimens. For those who enjoy collaborative and supportive environments, virtual DPP groups and online discussion boards such as Cancer Survivors Network allow individuals to share success stories and challenges and seek support from each another.

Peloton, an exercise equipment and media company that provides on-demand fitness classes, is another example of an SHC that considers community as one of its strengths.14 Compared to in-person exercise classes where participants may only see each other a couple of times a week, Peloton’s presence on social media allows its members to stay connected between classes. Facebook groups run the range from the Official Peloton Mom Group to Super Newbie Peloton Riders, Peloton Weight Watchers, Peloton Fitter Over 50 and Beyond, and Peloton Military & Veterans. Anecdotal evidence shows that these communities help improve members’ mental health and overall well-being—they provide a community to support each other not only during a cycling class, but also through major life transitions.

Enabled by digital technology and behavioral science

The use of technologies such as mobile apps, fitness trackers, and GPS-enabled devices is a key function of advanced SHCs, as is the use of behavioral science. The following examples show how some of these communities are leveraging various technologies and behavioral science to (1) increase access and convenience (2) inform behavioral interventions, and (3) facilitate data collection.

Increase access and convenience

One-on-one and group DPPs have been operating successfully for several decades out of brick-and-mortar locations, including community YMCAs. But with 100 million diabetic or prediabetic individuals in the United States alone,15 it might not be possible to serve everyone from such locations. Companies such as Omada Health, Noom, and many others have brought decades of evidence-based weight management programs and the CDC's National DPP program to scale by making them accessible and convenient through a mobile platform.

A digital interface can also make chronic disease management programs more accessible and convenient for individuals who live in rural and remote locations, as demonstrated by mySugr, a diabetes management company. In November 2018, mySugr launched a program with the Montana Primary Care Association to bring its diabetes management solution to people in rural and frontier Montana—some of whom live hours from doctors, hospitals, and supplies.16 While access to reliable internet can be a challenge in rural and remote areas, mySugr has found that Bluetooth meters don’t require internet to sync data to the app. Intermittent access to internet, however, is needed to chat with mySugr’s diabetes coaches. Alternatively, coaching sessions can also take place via phone calls when there is no internet access.17

Inform behavioral interventions

Clinicas del Azucar (which translates to “sugar clinics”) is a private network of diabetes and hypertension clinics in Mexico. With 30,000 patients using it over seven years, the network has volumes of data. Behavioral scientists are working with the clinics to segment consumers based on motivational profiles—a framework that helps them understand why some individuals adhere to a diabetes management program while others don’t. With these profiles, the clinics are exploring ways to incorporate targeted behavioral nudges to encourage patients to follow clinicians’ recommendations. This could include offering choices within an incentive scheme designed to address the patient’s specific motivational profile.18

Facilitate data collection

Geographic communities are leveraging technology, too. AIR Louisville made GPS-enabled “smart” inhalers available to individuals who have asthma in Louisville, Kentucky. Each time an individual took a puff, the inhaler logged the location, time, weather, and pollutants in the air. The individual then received notifications about bad air quality days and information that helped predict the time and location of asthma attacks. The data was also used to calculate the health care costs of poor air quality and was shared with city officials to understand where to concentrate air purification efforts.19

As data platforms such as Apple HealthKitTM20 developer software and Google’s Android ResearchStack become more advanced and widely adopted, SHCs will likely be better positioned to collect, analyze, and act on the data collected within their communities, provided they can overcome privacy and security challenges.

Meaningfully use data to improve outcomes

As technology makes data collection and data sharing easier, SHCs are using data to (1) predict risk (2) create a continuous learning loop through experimentation and innovation, and (3) conduct research and evaluation.

Predict risk

The Chicago Department of Public Health and the Department of Innovation and Technology created a predictive analytic model to help prioritize health inspections of retail food establishments. The tool combines information from various city data on Chicago’s open data portal with sophisticated analytic techniques to identify risk factors most likely to result in health code violations. Data includes a range of 311 data21 such as nearby sanitation complaints, previous inspection results, food license history, and outdoor temperature. Violations most likely to lead to food-borne illness were identified over seven days earlier using predictive analytics.22

As data sources become richer and more numerous, SHCs will likely need analytics, artificial intelligence (AI), and future technologies to make sense of all the data and determine the best course of action to predict and prevent health risks.

Create a continuous learning loop through experimentation and innovation

Health and wellness programs that are delivered through an app have significant flexibility to experiment and determine how to most effectively engage with participants to help them achieve their goals. Noom, a company that delivers its DPP and Healthy Weight program through a mobile platform with human coaching, uses data to improve the product in real time.23 With its Healthy Weight program, it can experiment with the content of the app or the timing of text messages to see if these tweaks translate into higher engagement. User response to these new engagement efforts can help the company fine tune the overall Healthy Weight program, creating a continuous and iterative learning and improvement loop.

Conduct research and evaluation

Many SHCs conduct research to evaluate their own programs, and some may form primarily to promote research on a specific disease condition or to give individuals the opportunity to opt into a larger research study (for example, 23andMe’s Global Genetics Project, which aims to increase genetic research in underrepresented populations24). Amstelhuis–Living Lab is a residential community for senior citizens in Amsterdam and the site of the Urban Vitality research program through the Amsterdam University of Applied Sciences.25 Students, lecturers, and researchers from the school regularly spend time in the community talking to residents, observing them, and administering questionnaires. Current research topics include an exercise and fall prevention study and a nutrition, food, and weight management study.

Data collection and program evaluation are key to understanding whether an SHC is achieving its goal. Most of the people we interviewed are collecting data to help evaluate their programs. While some can use real-time data analysis and real-world data, others are planning multiyear longitudinal studies to measure impact. Healthy New Towns, a combined initiative by England’s National Health Service (NHS) and 10 housing developments across the country, is conducting one such program of work. Its goal is to create healthy communities by planning and designing a healthy built environment (such as clean air and safe streets), creating innovative health models and encouraging strong and connected communities. The evaluation work is funded by the National Institute for Health Research and driven by a collaboration between site leads and academic partners (i.e., universities).26 As SHCs are established, they should have a plan in place to evaluate progress against goals. SHCs may wish to engage governments, foundations, and academic institutions to fund or independently carry out these evaluations as establishing impact on health outcomes will likely be required in some SHC funding structures.

Enable new and innovative ecosystems

Enabling new and innovative ecosystems composed of public and private entities is another essential element of SHCs. England's Healthy New Towns program, for example, places particular emphasis on sharing information with other public agencies, local governments, housing developers, and trade unions to promote best practices. Congress’ bipartisan Food is Medicine Working Group is bringing together stakeholders from the agriculture and health policy sectors by emphasizing the link between nutrition programs and health outcomes.27 The Chicago Department of Public Health’s Healthy Chicago 2.0 initiative partners with local philanthropic organizations to align grantee goals with department goals, rather than forcing grantees to split their attention between different measures. It also leverages data from previously untapped sources such as NASA to improve its ability to monitor community health. And WW is partnering with Kohl’s to hold workshops and wellness sessions inside the retailer’s brick and mortar Chicago location.

Funding of SHCs is also often collaborative, brought together from different industry sectors and organizations. NIH, for example, funds Noom research; the BUILD Health Challenge awardees receive funds that have been aggregated by a funding collaborative that includes several different foundations, as well as a local matching source; and public and private health care payers reimburse for DPP apps. Blue Cross Blue Shield of Massachusetts pays for member meals from Community Servings, a nonprofit food program that provides medically tailored, home-delivered meals and nutrition education to critically ill individuals and their families.28

Doctors, nurses, and other health care providers can also play a key role as connectors to the traditional health care system. In the case of AIR Louisville, data generated from smart inhalers were shared with patients’ physicians. This gave doctors insight into how often their patients were using emergency inhalers and helped them determine the most effective asthma medication dosage for each patient to avoid excessive use of emergency inhalers. Meanwhile, Fresh Food Farmacy, an initiative launched by a Geisinger Health System community hospital in 2017, is designed to address the social determinants of health through an ecosystem approach that views “food as medicine.” Through this initiative, physicians write “prescriptions” for high-risk diabetes patients who cannot afford or do not have access to fresh, healthy food. They can then pick up recipes and free groceries from the Farmacy’s food bank and receive the education and support needed to manage their diabetes with healthier food choices.29

As stakeholders work together to advance SHCs, they will need an integrating body that can bring partners together to (1) establish shared values, (2) develop, implement, and invest in strategic planning, goal setting, and needs assessment, (3) manage and integrate funding from diverse sources and programs, (4) analyze shared impact, and (5) ensure accountability and continuous quality improvement. One way to achieve this is by establishing a Community Funding Hub which, through a central integrator or “hub,” could bring together and coordinate previously siloed sectors and funding streams. This position could be taken on by one of the SHC stakeholders, including government, or can be established as a new entity.30

WW International: A virtual community at work

WW International is an example of a virtual SHC which also has physical locations. With a focus on weight loss, health, and wellness, the program uses a points system that encourages and empowers individuals to eat healthy food and track their eating via their mobile app. Individuals can also receive and provide support through in-person or digital community meetings and receive personalized information and motivation through a personal online/phone coach, and a host of digital tools.

WW is an illustrative example of SHCs, as it contains all the key elements:31

- It empowers individuals to proactively manage their health and well-being. WW empowers users to make choices that can proactively improve health, well-being, and quality of life to reduce adverse health outcomes in the future.

- It fosters a sense of community and belonging. Virtual and in-person community meetings foster a sense of community and belonging.

- It uses digital technology and behavioral science. It uses a mobile application to enable users to enter/track data and seek information (for example, fitness tips, recipes) and deploys the use of coaching and guides to support adherence and uptake of behaviors associated with healthy, active living. Behavioral nudges, such as a rewards program for healthy habits, are also incorporated into the program.

- It uses data to meaningfully improve outcomes. This allows users to track their progress. It also gains consent to use and share data to target programming to further improve health and fitness outcomes for users.

- It creates new and innovative ecosystems. WW is now partnering with retail to enhance its physical presence in the community. To drive more traffic to its store, a Kohl’s in Chicago will open a WW-branded studio, offering workshops and diet coaching.32

Healthy Chicago 2.0: A geographic community at work

In 2016, the City of Chicago launched Healthy Chicago 2.0, the second phase of the city’s multi-stakeholder plan to maximize its residents’ health and well-being. Led by then-Mayor Rahm Emanuel and the Chicago Department of Public Health, the four-year plan’s vision is to reduce health inequities by focusing on expanding partnerships and community engagement, addressing the root causes of health, increasing access to health care and human services, improving health outcomes, and utilizing and maximizing data and research.33 There are 82 objectives and 200 strategies to reach 30 goals.

Healthy Chicago 2.0 is an example of a geographic SHC in the following ways:

- It empowers individuals to proactively manage their health and well-being. Healthy Chicago 2.0 focuses on proactive health and well-being by addressing social determinants of health through strategies including promoting healthy food access, expanding the bike-share program, and promoting and supporting self-management programs for chronic disease, among others.

- It fosters a sense of community and belonging. Healthy Chicago 2.0 was developed in response to a community health assessment that engaged hundreds of stakeholders from different parts of the city. As part of the work, the city communicates with community residents regarding efforts and educates communities on public health issues.

- It uses digital technology and behavioral science. The program leverages technology in new and innovative ways. For example, the city tracked public Twitter messages using a supervised learning algorithm for possible foodborne illness complaints that may have been linked to food consumed in food establishments that are under the purview of the city’s food inspection, leading to early and targeted inspections.34 Healthy Chicago 2.0 has not yet incorporated behavioral science into its strategy but has begun looking into how behavioral science complement existing strategies.

- It uses data to meaningfully improve outcomes. It looks to novel data sources to proactively determine which areas are more at risk for poor health outcomes. Specifically, using data from the Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) program to determine where to target proactive lead paint inspections and satellite data from NASA to monitor air quality.

- It creates new and innovative ecosystems. In addition to working with other government agencies, Healthy Chicago 2.0 also works with community organizations, academia, businesses, and philanthropic organizations to align on health outcome measures and coordinate investments in communities.

How to take SHCs to the next level

The SHC leaders we interviewed revealed some challenges in creating and sustaining effective SHCs. For example, it is much easier to attract and retain the “wealthy, worried, and well” than those who lack the motivation or resources to improve their health. SHCs must embed strategies for helping the poor, unmotivated, and unhealthy to adopt healthy behaviors using the science of healthy behavior change and interventions that address the social determinants of health. New Jersey’s Department of Community Affairs is addressing social determinants of health by providing housing vouchers to homeless individuals who are high utilizers of emergency departments.35 One of a number of pilot projects in the state, Housing First is a joint partnership of local health care and social services, and employs case managers to offer support services including assistance enrolling in Medicaid, Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), food stamps, substance abuse treatment, mental health counseling, domestic violence prevention, and employment training.

Like many transformative initiatives, SHC leaders must identify seed funding to get started, and develop a sustainable business model that can be scaled. SHCs that can demonstrate improved health outcomes through rigorous monitoring and evaluation of their programs will increase their chances of securing sustainable funding through public or private investments, health care payers, or individuals willing to pay out of pocket.

Finally, SHCs could face privacy and data security challenges when it comes to collecting and sharing data. One SHC interviewee initially hoped to provide in-home sensors to seniors to help predict the risk of falls. Seniors, however, were concerned that the sensors could create privacy issues. Another SHC interviewee wanted to combine multiple datasets from various sources but found that data-sharing agreements could prevent the full exploration of data sets and data integration. SHCs might be able to encourage users to share their data if they are completely transparent about how information will be collected, stored, secured, shared, used, and when/if it will be deleted. When faced with data restrictions, they can identify proxy data sets that can help them get the information they need.

How can today’s stakeholders get involved with SHCs?

As SHCs mature and proliferate, stakeholders such as governments, health systems, health plans, life sciences firms, and nontraditional health care companies, such as technology companies and retailers, can promote and support these communities.

Governments

Government agencies can lead or support SHCs in several ways. They can create pilots and payment models that stimulate the development of cost-effective SHCs through public health insurance programs like Medicare, Medicaid, Veterans Affairs, and the Military Health System in the United States. Through their national health services, governments around the world can build SHCs and recruit other public and private agencies to expand their reach. Funding or evaluating SHCs alongside foundations and academic institutions is another way government agencies can incentivize SHC growth.

Governments can also establish data-sharing agreements and then collect, analyze, and share data on local population needs with other players in the SHC ecosystem to collaborate on innovative solutions. Making information available to SHCs can help accelerate research and discovery, develop upstream solutions with predictive analytics, and empower individuals to make healthy choices. Additionally, governments can help SHCs by developing and/or supporting SHCs’ technological infrastructure and governance, including standardization and security of data.

Providers, payers, life sciences companies, and nontraditional health care players

Health systems, health plans, physicians, life sciences companies, and nontraditional health care players such as technology companies and retailers may want to partner with and participate in SHCs as part of their digital and consumer engagement strategies. Early movers on SHCs may be able to establish consumer loyalty, improve behaviors such as medication adherence, thrive in value-based care arrangements, increase access, and reduce costs. As organizations build or participate in SHCs, data collection, analytics, and ongoing monitoring and evaluation of SHCs will help make them more effectively improve health and well-being.

Looking ahead: What does the future hold?

Many of today’s SHCs display one or more of the essential ingredients of mature SHCs. But they operate in silos, largely isolated from each other and the geographic communities in which people live. As technologies such as the Internet of Things (IoT) connect even more people and more advanced devices to one another, SHCs will likely become larger. Per Metcalfe’s law, the growth of these communities will make them more powerful; they will capture more data from their growing membership and the many devices their members use, rendering the data richer and more comprehensive. This will allow SHCs to conduct more robust research, learn more about the science of behavior change, and create cohesive and supportive social groups based on common interests and values.

In the future, we expect many more of the communities in which we live, work, and interact (both virtually and physically) to consist of a web of interconnected SHCs. These communities could constitute an ecosystem of public and private players that support each other. They may address social determinants of health, such as access to food, transportation, and employment; incorporate emerging technologies such as artificial intelligence, augmented/virtual reality, robotics, and radically interoperable data; use behavioral science to empower individuals to eat right and exercise; and detect and treat disease at its earliest stages using genomics and precision medicine.

SHCs may also communicate and integrate with aspects of health care. Physicians may be able to write prescriptions for digital wellness programs, health plans and employers may reimburse for such programs, and data could be shared seamlessly between all stakeholders. Most importantly, individuals can own their health care data, allowing them to make informed decisions about their health. As SHCs mature and proliferate, their governance and funding approaches could become more sophisticated, affording them the management and resources necessary to empower communities to invest in their own health and well-being—not just to stave off illness, but to reach their full physical and mental potential.

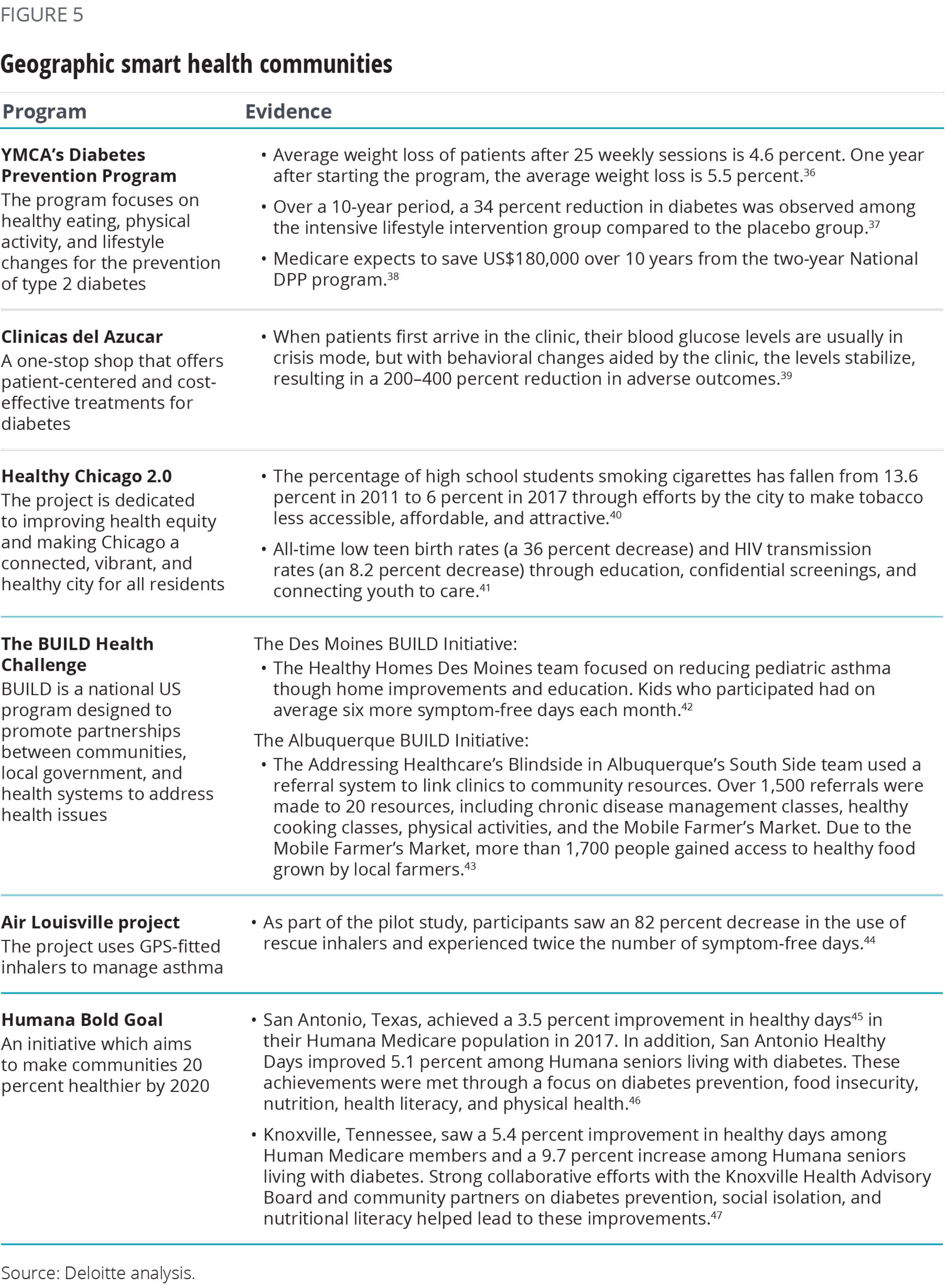

Appendix

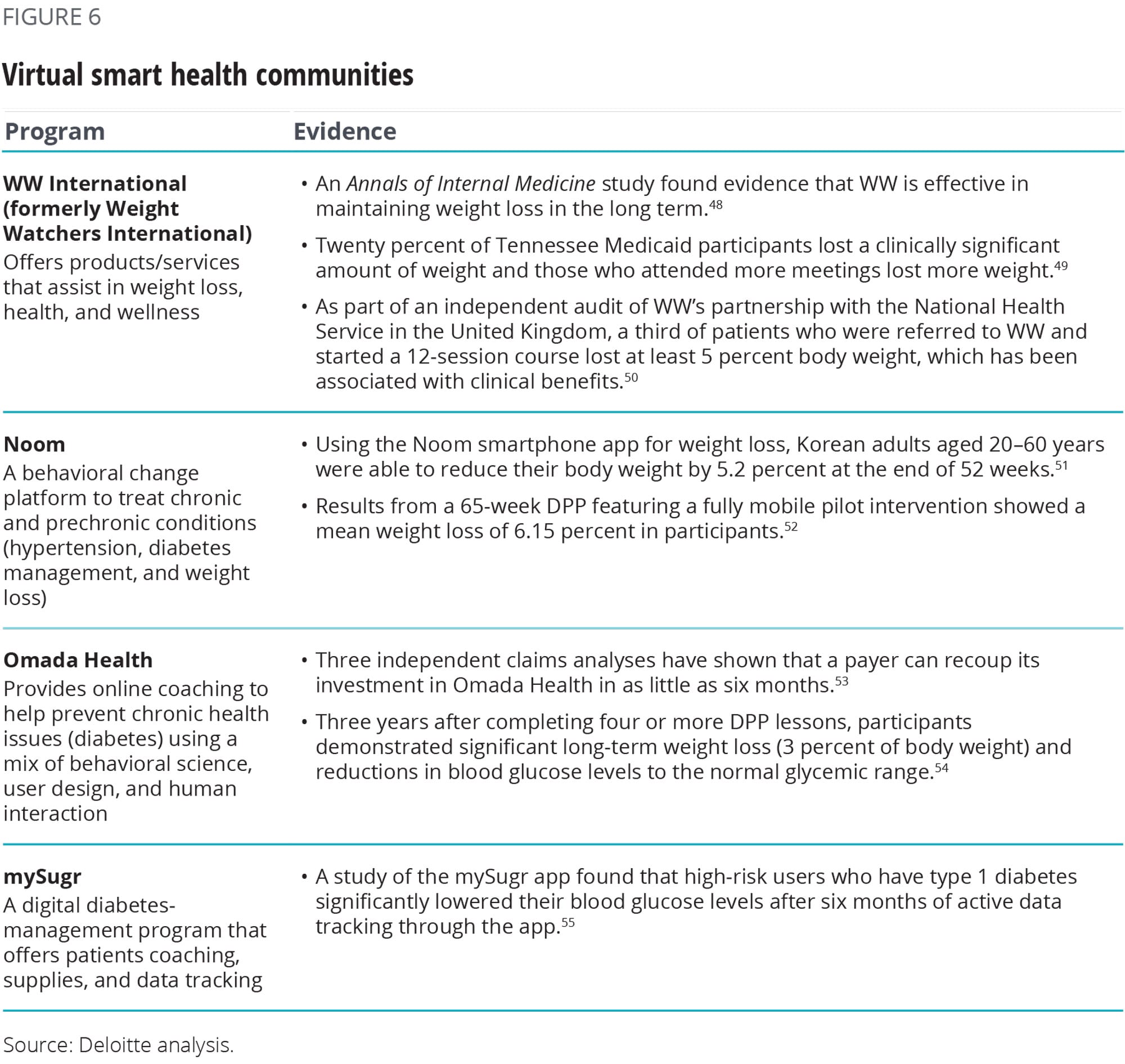

Geographic and virtual smart health communities: Landscape and outcomes

Many different smart health community initiatives are still early in development and do not yet have outcomes data, but some examples of programs that have demonstrated improved health outcomes, and even cost savings, are listed below.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.

Explore the Future of Health

-

Health care Collection

-

The health plan of tomorrow Article5 years ago

-

Forces of change in health care Article5 years ago

-

Showing cybersecurity's value to health care leadership Article5 years ago

-

Creating a treasure trove of data for health plans Article6 years ago

-

Health systems have a growing strategic focus on analytics Article6 years ago