The CDO’s responsibilities are important—and growing. The office of the CDO (OCDO) was once intended mainly to improve data availability, quality, and compliance. Today, however, many organizations are beginning to recognize the operational and mission value of their data, and OCDOs are being called upon to take the lead in transforming many essential business processes. Yet, despite the federal government’s increasing emphasis on modernizing data management, many agencies still find themselves struggling to deal with an ocean of data with only islands of utility.

Having a data strategy is an important starting point for organizations. Data strategy is what links that vision of deriving operational value from data to the resources needed to make that vision a reality. Developing an effective data strategy is an important step, but it can’t be the only step. CDOs need the organization to execute that strategy. After all, creating new value can imply changes to how an organization is currently doing business. As relatively new additions to the C-suite, CDOs may be unable to individually dictate that change to other leaders. Therefore, if data strategies are to succeed, CDOs may need operational structures that they can use to help drive change across the organization.

As the CDO role matures, expectations shift

The federal government has been at the forefront of creating CDO roles and offices, for two reasons.

Initially, the creation of CDO roles was driven largely by compliance. Legislation such as the Foundations of Evidence-Based Policy Making Act of 2018 required many agencies to create such CDO roles and draft data strategies.1 However, while agencies may have created these positions to comply with requirements, many were also exploring how new technologies such as artificial intelligence and machine learning could improve overall mission performance.2 As CDOs demonstrated their value in providing the high-quality data needed by these new technologies, the second driver of CDOs—as assets to operations and decision-making—began to grow.

This led to a shift in how organizations saw the value of CDOs: from purely being a compliance exercise that ensured clean data to one that could have measurable impacts on important operations. This shift is reflected in who CDOs work for. A survey of Federal CDOs found that, from 2021 to 2022, the percentage of responding CDOs reporting to a chief operating officer doubled from 10% to 20%, while the percentage of responding CDOs reporting to a chief information officer (CIO) declined from about 30% to 20%.3

Driving change from the CDO office can be hard

In many ways, the shift in the CDO role represents success as CDOs may become increasingly important to core mission operations. But that success can also come at a price. Now, CDOs should figure out how to drive change from their part of the organization. As the new kid on the block, convincing other executives to change their ways can be hard for a variety of reasons:

Limited authority and budget. Where the CDO role is placed within the organization can affect its level of visibility, authority, and influence. Some CDOs report directly to a chief executive officer, potentially giving them greater latitude in budget negotiations compared to CDOs who report to a CIO or chief technology officer (CTO). The more layers of leadership a CDO must work through, the more likely their authority—and budget—could be diminished.

Limited technical scope. While CDOs are responsible for data governance and data quality, they usually aren’t the owners of data systems. System owners often report to a chief information security officer and could have their own way of managing their systems and data, resulting in silos that could impact the OCDO’s effectiveness.

Limited leadership awareness. Another challenge can be the lack of data literacy among senior management. It’s not enough for CDOs to hire data specialists; they need the active support of executive leaders. On their own, CDOs may not be able to affect all their agency’s data-related work; they may need to rely on their peers to help push the agency’s efforts toward improving data collection and usage. And the shift in culture, this could require starts at the top, with the assistance of fellow executive leaders to communicate the importance of data standardization and empower the workforce to use these data in making decisions and providing insights.

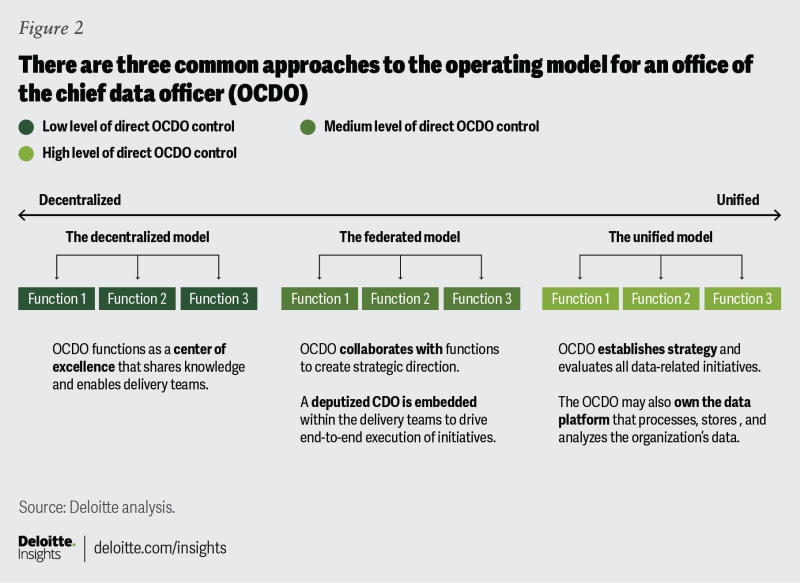

Ultimately, these limitations could mean that CDOs can rarely dictate change directly. Rather, they should find the right operating model to help spread change across an organization. Yet, many CDOs have inherited an operating model driven by legislative trends or legacy structures within the organization, while CDOs are tasked with leading rapid change as per digital trends. This mismatch can mean that, to execute their data strategy, CDOs also need the right operational structure.

Choosing the right operating model for the right organization

So what is the right operational model for an OCDO? Like many hard questions, the answer is “it depends.”

The right operational model will help achieve the vision and data strategy of the organization. This strategy can set out the goals the CDO is trying to achieve and the service offerings that are important to achieve them. Simultaneously, the governance structure—especially the question of who the CDO reports to—can determine how the CDO’s success is measured and what resources they have to deliver their service offerings. With the service offerings and governance on the table, CDOs can then make informed decisions about the right model and its components to satisfy both (figure 1).