Convergence of technology in government Power of AI, digital reality, and digital twin

16 minute read

11 March 2020

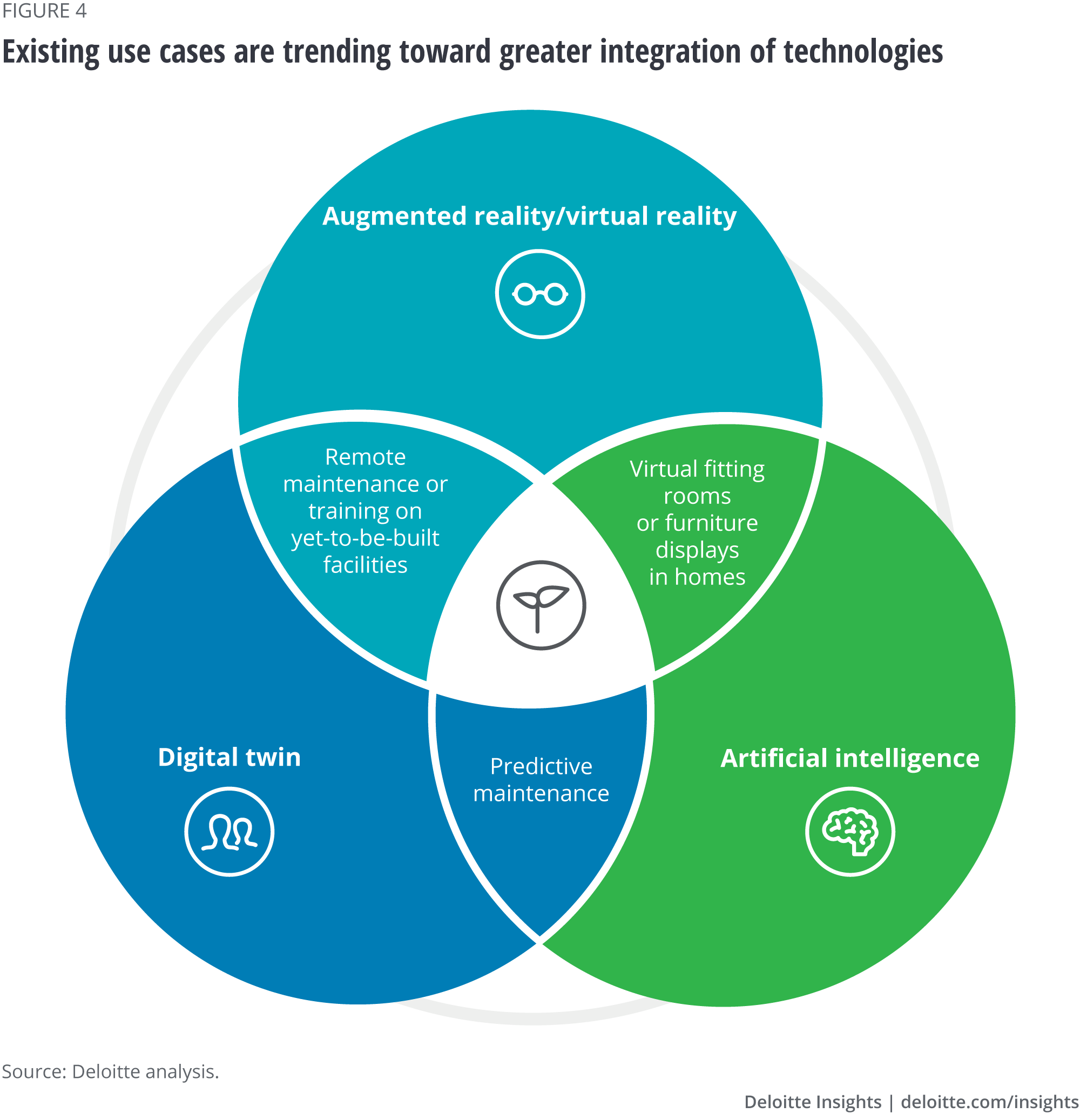

A single technology is sometimes used to solve a single problem, but this can entail certain risks for governments. Instead, as technologies become more connected, their convergence becomes crucial.

Key Takeaways

The limits of single-technology use

“Okay, Houston, we’ve had a problem here.”1 The now famous words were transmitted through space down to Houston after the Apollo 13 crew attempted to stir the cryogenic oxygen tanks. The otherwise-standard procedure caused a series of electrical shorts and subsequent problems, leaving the command module unable to generate power, provide oxygen, or produce water. Bounded by space thousands of miles from Earth, the situation was dire for the Apollo 13 crew.

Learn more

Explore the Government & Public services collection

Learn about Deloitte's services

Go straight to smart. Get the Deloitte Insights app

NASA engineers on the ground had very little information. The crew shared their observations, and the spacecraft was transmitting some data, but these inputs didn’t give engineers on the ground a perfect picture. To better understand what had happened and what consequences the crew faced, the NASA team in Houston used a mirrored system of the Apollo 13 spacecraft, allowing them to duplicate the situation as accurately as possible. NASA had effectively created a twin—in this case, anomaly and all—on which they could work at the space center in Houston.2 Indeed, with the information gleaned from this system, engineers in Houston were able to produce a solution by modifying an air filter, allowing the Apollo 13 crew to return safely to earth on April 17, 1970.

What if the team in Houston had access to more data in real time; access to virtual reality to inspect, test, and solve problems; and AI to identify problems before they happened regardless of distance? Perhaps the electrical short would never have occurred in the spacecraft, and the mission would have continued as planned. While such systems didn’t exist in 1970, they do today.

These modern technologies can complement each other, offering new possibilities for visualization, instruction, informing, communication, collaboration, and engagement in planning complex systems and operations. But such systems are not singular technologies. Rather, they are made up of digital twins, AI, and immersive technologies such as virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR).

As government leaders move toward the next technological horizon, it is critical to understand how technologies used together can create new possibilities. If government leaders focus solely on separate technologies for single-problem sets, they potentially risk buying them without the necessary support or infrastructure. Technologies such as AI, VR/AR, and the digital twin can work together seamlessly to open exciting and new opportunities for government—for example, real-time decision support of and simulation for a country’s trip back to the moon. Achieving this goal requires not only the typical cross-functional collaboration between leaders but also understanding the technology convergence that lies ahead and how best to capitalize on it.

What are these new technologies?

With so many different technology terms being introduced every day, it can be difficult to understand what any new technology really is—and, just as importantly, what it isn’t. Here, we focus on a few that could be key components of technology convergence.

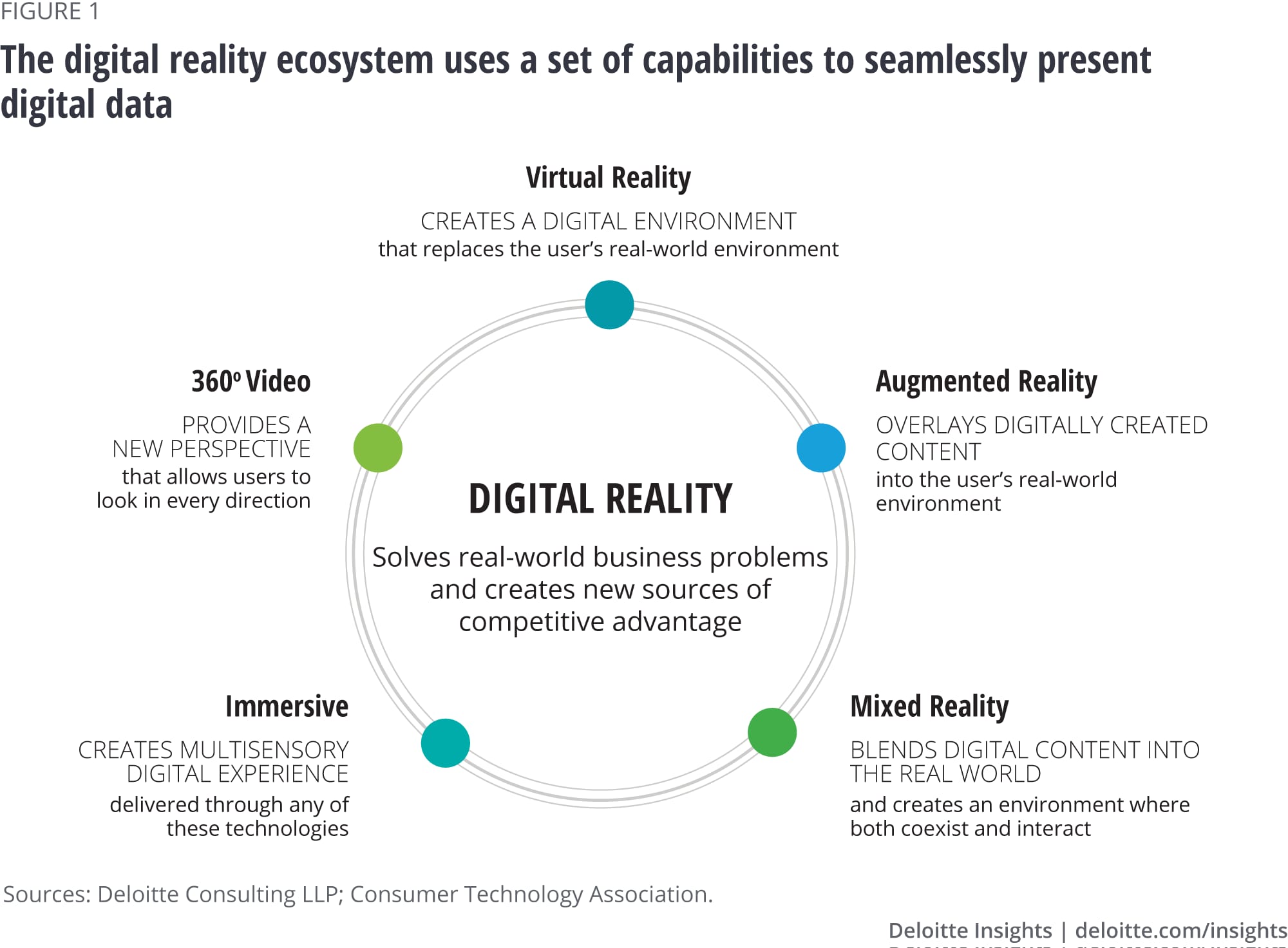

Digital reality

Digital reality is our term for the range of immersive technologies that bring digital information into the physical world, including AR, VR, mixed reality, 360-degree video, and immersive experience capabilities (figure 1).

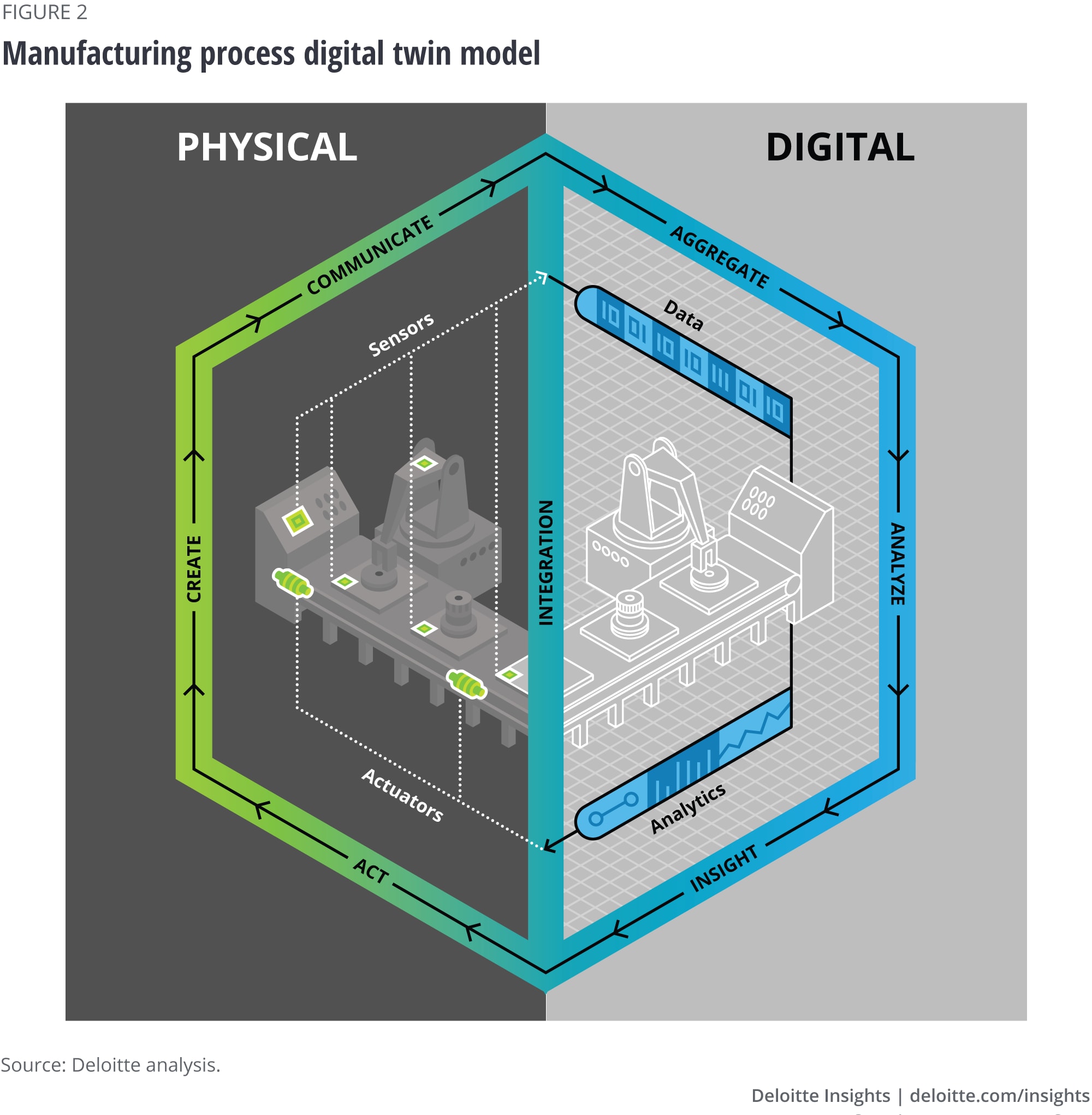

Digital twin

A digital twin, as we’ve written elsewhere, is “an evolving digital profile of the historical and current behavior of a physical object or process that helps optimize business performance.”3 It is the exact digital replica of a physical entity, bringing the benefits of digital analysis to the physical world (figure 2).

Digital twin applications include, but are not limited to:

- Manufacturing—model or simulate physical systems for optimization

- Aviation—predictive maintenance

- Health care—optimization of hospital life cycles

- Urban development—optimization and risk-free testing

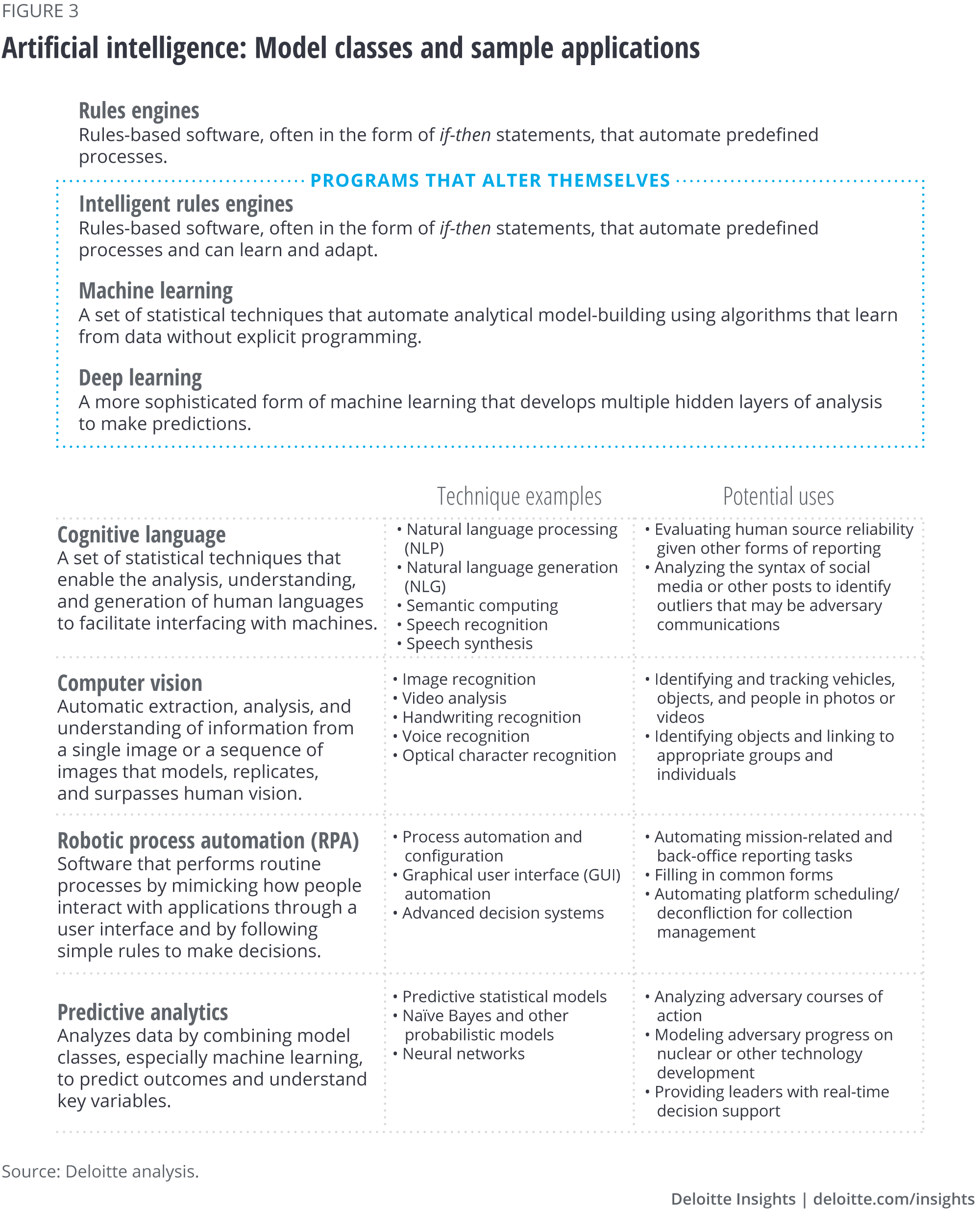

Artificial intelligence

There is perhaps no single, universally agreed-upon definition of AI, but a good one is technologies that can perform and/or augment tasks, better inform decisions, and accomplish objectives that have traditionally required human intelligence, such as planning, reasoning from partial or uncertain information, and learning. AI tools can often be classified both by how they operate and what they do (figure 3).

A palette of technologies

The evolution of technology often produces isolated solutions: one problem, one technological solution. The phone helped people overcome distance and communicate in real-time. The internet allowed people to access volumes of otherwise-inaccessible information. And the digital camera transformed how people captured moments and memories through photos. But the real revolutionary development came when these tools were congregated into a single device such as the smartphone. Through technology convergence, users develop new tools, methods, and solutions that create process efficiencies, save money, and lead to further innovation.

So far VR/AR, AI, and digital twins are being used primarily in a “single-problem, single-technology solution” manner. Separately, these technologies offer novel solutions to hosts of distinct problems. VR, for instance, has been used to speed learning through immersive and life-like scenarios. Digital twins can increase production rates and allow teams to monitor complex physical systems more precisely. AI has matured to the point that it can analyze mountains of data and produce insights faster than humans. While these technologies have enormous potential even as isolated solutions, like the smartphone, their convergence promises even-greater possibilities.

Indeed, we are already seeing the value of their convergence. For example, Dubai Electricity and Water Authority, in partnership with Siemens, has combined AI and machine learning with a thermodynamic digital twin gas turbine to improve operation efficiency and save an estimated approximately US$4.6 million dollars annually.4 The digital twin provides real-time information about specific components or issues, while the AI component is able to process the massive amount of data to notify system managers about problems that are developing or the best time to conduct maintenance.

At the engineering and industrial software company, Aveva, remote engineering teams are using VR headsets and the digital twin to guide onsite teams through diagnostic and remedial processes.5 Rather than identifying a problem and attempting to communicate a complex situation over the phone or email, the combination of digital twin and VR allows remote engineers to see exactly what’s going on in real-time. The 3D virtual presentation greatly improves communication, therefore, simplifying the diagnostic or remedial process.6

The convergence of these technologies isn’t limited to large industrial processes or companies. Digital twin and immersive technologies have proven to be fantastic tools for governments in disaster response. In 2018, when 12 young soccer players and their coach were trapped in a cave by rising flood waters, rescuers combined multiple data sources to create a 3D digital twin of the cave.7 This helped to calculate how best to divert water to drain the cave, understand where other access points may be, and help divers calculate what areas would be flooded and what their air requirements would be. Over the close to three weeks of the rescue operation, these models proved vital to safe rescue of the boys and their coach.

The benefits of this convergence of AI, digital twin, and AR/VR will be felt by governments, the private sector, and the public because the value of these technologies used together will only increase. Understanding how this convergence will occur and how best to prepare will be important for not only saving time and money in buying today’s technologies, but also opening entirely new possibilities for solving government’s biggest challenges tomorrow.

Technology isn’t just converging; it needs to converge

Technological convergence means that previously independent technologies need to be designed and bought with each other in mind. This could create potential pitfalls for government leaders. No longer can government buy a single technology for a single problem; doing so can create the risks of costly duplication, a loss of capability, and limited opportunities for future development.

Risk #1: Not having the right capabilities

Convergence means that advanced technologies increasingly rely on each other to function properly. Pursuing each independently risks overlooking a key component. For example, many of today’s military war-games are still played with dice on a table top, basically a customized board game. These table-top games have proven remarkably resistant to computerization over the years, largely because simply adopting some advanced AI versions of those games alone would not be enough to improve their performance. The games also need large amounts of real-world data to ensure they accurately represent real machines in warfare. In the words of the US Marine Corps’ Wargaming Division: “We do not currently collect the data we need systematically; we lack the processes and technology to make sense of the data we do collect; and we do not leverage the data we have to identify the decision space in manning, training, and equipping the force.”8 In other words, trying to improve war-gaming with AI or digital reality without including the real-world data that can only come from the sensors that enable digital twins may not produce better results than the dice-based war-games being used today.

Risk #2: Costly duplication of effort

Governments are no stranger to silos or duplication of effort, but they can be especially damaging for smaller governments. One major IT project or capital investment can consume major portions of a government agency’s budget. So if that investment is made in a tool that is already available elsewhere, it can be a significant opportunity lost. Take just AI as one example: When the Delaware Department of Services for Children, Youth, and their Families (DSCYF) upgraded its case management system, it needed search appliances and AI recommendation systems.9 By finding existing tools already in use by other agencies on the cloud, DSCYF was able to save time and money in its deployment. While this challenge is not new, the convergence of technologies makes it even more acute. Now, not only do government leaders need to check for existing technology of one type, they also need to check for multiple types of technology in many different areas ranging from learning to simulation to acquisition, to ensure that there are no existing tools that may meet their needs.

Risk #3: Limits on future development

Finally, even if the development of a single technology goes perfectly without duplication of effort or loss of functionality, that success may be fleeting if other technology is not taken into account. Take virtual training as an example. Even if the virtual training environment has hyper- realistic scenes and vehicles and can connect to the most advanced AI for humans to train against, without a digital twin, it may be a perfect representation of only this moment in time. As soon as new vehicles come out or new buildings are built, the entire training environment would need significant, costly upgrades. What is needed are the organizational, procedural, and technical connections to incorporate the digital twins of new vehicles and infrastructure.

With the US Army spending hundreds of millions on a virtual training environment, the Department of Defense spending tens of millions of dollars on new war-gaming capabilities, and the US government investing in geographic information systems and other tools around the country, there is an immediate need to get this right.10

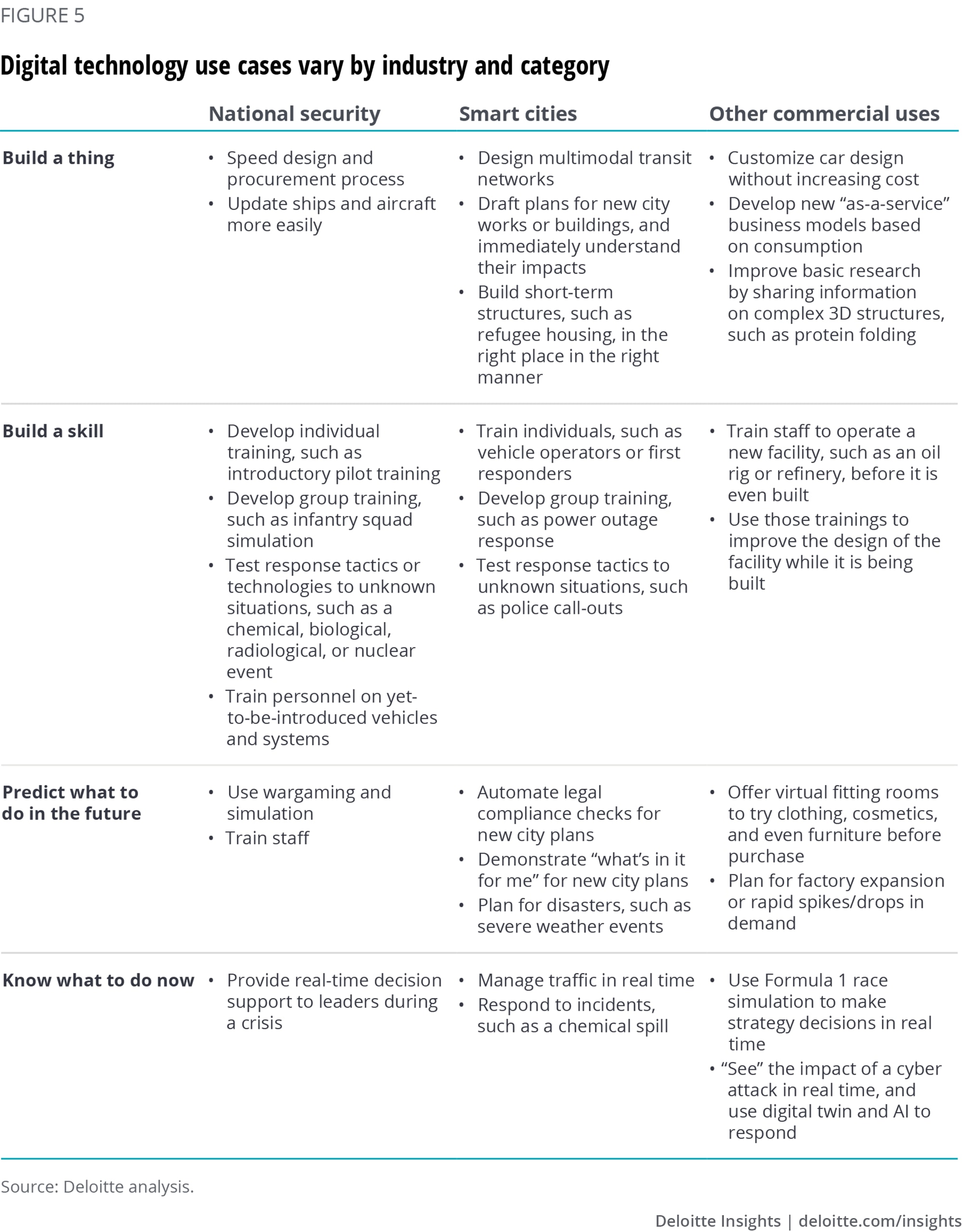

Three paths, one destination

If the convergence of AI, AR/VR, and digital twins is not only desirable but needed, it begs the question, what would such convergence actually look like? What can it do that is new? The short answer is, it all depends on what you need it to do.

Building

Build a thing

Adding AI and AR/VR to the digital twin can open up new possibilities across the life cycle of anything from a tank to a transit line. For example, commercial real estate developers are already using these technologies to better understand how a project will take shape and affect the environment or city skyline, and monitor its progress.11 On a larger scale, Virtual Singapore is a US$73-million-dollar dynamic 3D city model, that when complete, will be capable of supporting planning, decision-making, testing, and research to solve some of Singapore most important urban challenges.12 This example, while impressive, is still not common among all developers. Now just imagine if this tech convergence was used at scale to develop everything from buildings and factories, to city infrastructure and military bases.

Build a skill

The benefits of using VR/AR to improve training, especially on rare or dangerous tasks, is well documented.13 However, adding AI and digital twins to the mix can have truly impressive results. For example, the US Air Force’s Pilot Training Next program uses those technologies to halve the time required to train pilots.14

But even those impressive results are only part of the story. Once the power of tech convergence is understood, such tools become laboratories for improving the interaction between humans and machines. Take the famous example of Three Mile Island in Pennsylvania, where worker stress, a critical warning light hidden behind a panel, and other factors all came together to result in a nuclear meltdown in 1979.15 If that reactor crew could have trained in a virtual environment together before the accident, it is possible that they could have identified ergonomic issues such as hidden buttons and practiced processes to reduce the stress of real emergencies, perhaps even avoiding the accident altogether.

Understanding

Predict what to do in the future

The ability of digital reality, digital twins, and AI to link physical and digital worlds makes them powerful tools to learn more about the world around us. Guessing how people will act in the future is a challenge military leaders and city planners alike face. Creating a digital twin of a city or military force can allow for far more accurate simulations than today’s statistical city models or dice-based war-games.

San Diego is using that approach to tackle downtown traffic. Previously, it would have likely only considered a handful of road-widening projects for study, but now it is able to compare many options, including fast rail lines or light rail systems. And the results showing the best solutions can be available within hours or days, not weeks. Those results can then show concerned citizens exactly how a new city works or proposed building project will impact them individually—not a general assessment, but how it will change their unique commute or view of the skyline.

Another significant challenge for governments and industry is environmental impact assessments and permitting. Understanding all of the impacts of a proposed project can be difficult and either slow down needed development or risk damaging delicate natural resources. But AI, the digital twin, and digital reality can help. AI is already helping governments to understand the impact of everything from rice production to manufacturing on complex ecosystems.16 Combining that information with digital twin can show how those impacts will affect a specific city, and VR and AR can help naturally visualize those findings for city planners and citizens alike. The result can be a significantly faster review process, which can enable faster development with less environmental impact.

Know what to do right now

Perhaps the ultimate expression of the convergence of AI, digital twin, and digital reality is the ability to do many of those same planning and simulation tasks, but in real-time. For example, Formula One teams use digital twins of cars and laser scans of race tracks paired with vast machine learning algorithms and human-in-the-loop simulators to come up with better race strategies than the competition’s.17 These tools are even used during the race to adjust to unforeseen consequences, such as rain showers or car damage.

There are clear applications of this high-intensity decision support in crisis management for both national and city leaders. We have explored what this might mean for intelligence analysts, for example, who may shift from giving static briefings to national leaders before a crisis, to sitting with leaders during a crisis updating models and giving advice in real-time.18 But these benefits apply not only to major crises but also minor crises such as a traffic jam on the way home from work. Real-time decision support can help traffic managers understand the impact of an accident or an unexpected snowfall, and react to minimize delays across the transit network.

Figure 5 offers examples of how tech convergence can be applied in different ways across different industries.

What does it take to get started?

The potential benefits of the convergence of AI, digital twin, and digital reality are fascinating, but if they are ever to be more than a pipe dream, organizations need to ask themselves, “What type of infrastructure do these technologies require?”. Cutting-edge technology operating in near–real time to create entirely new opportunities for governments sounds like a technical nightmare that could require massive capital investments. However, the reality may be a pleasant surprise to chief technology officers.

Know the compute requirements

Even massive-scale simulations of entire cities or whole armies may not require rooms full of mainframes or whole data centers. Compute requirements are not driven by the number or types of things within a scenario, but rather by how much they need to interact.19 So even some very large simulations can be done very quickly and affordably with limited compute requirements. In fact, some of early-stage experiments in MIT Media Lab’s CityScope city planning tool relied on a single laptop to run the digital twins, AI, and AR for the simulation.20

Find the right enablers

Once the initial fear of cost is overcome, you can find the right tools to make your vision a reality. This starts with defining your business need. In the words of Jordan Garrett of Dell technologies’ emerging technologies division, “Infrastructure will be driven by what you want to do. For example, use cases to design complex parts may need significant centralized high-power computing support to run all the computer-aided design (CAD) and simulations. On the other hand, many use cases in manufacturing may want a lighter edge-core-cloud model that can allow different facilities to operate independently.”21

Answer your questions, not all questions

When dealing with complex systems, even the best-resourced, highest-performance tools have their limits. Formula One race teams commonly use around 4,000 servers in the cloud to run their real-time simulations of race strategies and still face limitations. According to Randeep Singh, head of race strategy for the McLaren F1, “For a single race, there are more permutations on how a race can unfold than there are electrons in the universe. So you are never going to model everything. What we try and do is be really smart about using elements of machine learning and game theory to try and model what our competitors may do to stay a step ahead of them.”22 For government leaders, this means not modeling every last detail of every possible question—whether about a city, a war, or a disease outbreak—but only those questions that are most pertinent and within your control.

Solve the data challenge

Finally, while technology infrastructure may not be as big and frightening a hurdle as it first appears, data may be more so. AI, digital twins, and digital reality are each only as good as the data they receive. The more complex a scenario, the more likely that data will come from multiple platforms in multiple formats. Yet it all needs to work together seamlessly. Cleaning, formatting, and making all of that data usable within the time periods needed to make critical decisions is a major task and deserves significant thought before embarking on a solution.

Above all, work together toward a future vision

It is easy to think of technologies as single-shot solutions to a single problem. From navigating sailing ships to air traffic control, the most difficult problems require multiple technologies working together seamlessly. For government leaders, this means that you cannot think of technologies individually—buying VR for training here, a digital twin for acquisition here, and AI for decision-making here. The more complex these technologies get, the more they rely on each other. As a result, government leaders should consider pursuing these technologies with an eye toward that convergence, discovering how digital twins from the acquisition of a new aircraft will flow into the VR training pipeline for pilots or update the AI models that do predictive maintenance.

This means that leaders in learning, procurement, and technology must work together to understand their individual goals and how technology convergence can solve them collectively. Ignoring that convergence potentially risks duplicate programs, noninteroperable systems, and wasted time and money. The future is out there, but it can only be seen together.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.

More from the Government & public services collection

-

AI-augmented human services Article5 years ago

-

Government executives on AI Article5 years ago

-

Customer experience in government Collection

-

Artificial intelligence in government Collection

-

Charting new pathways Article5 years ago